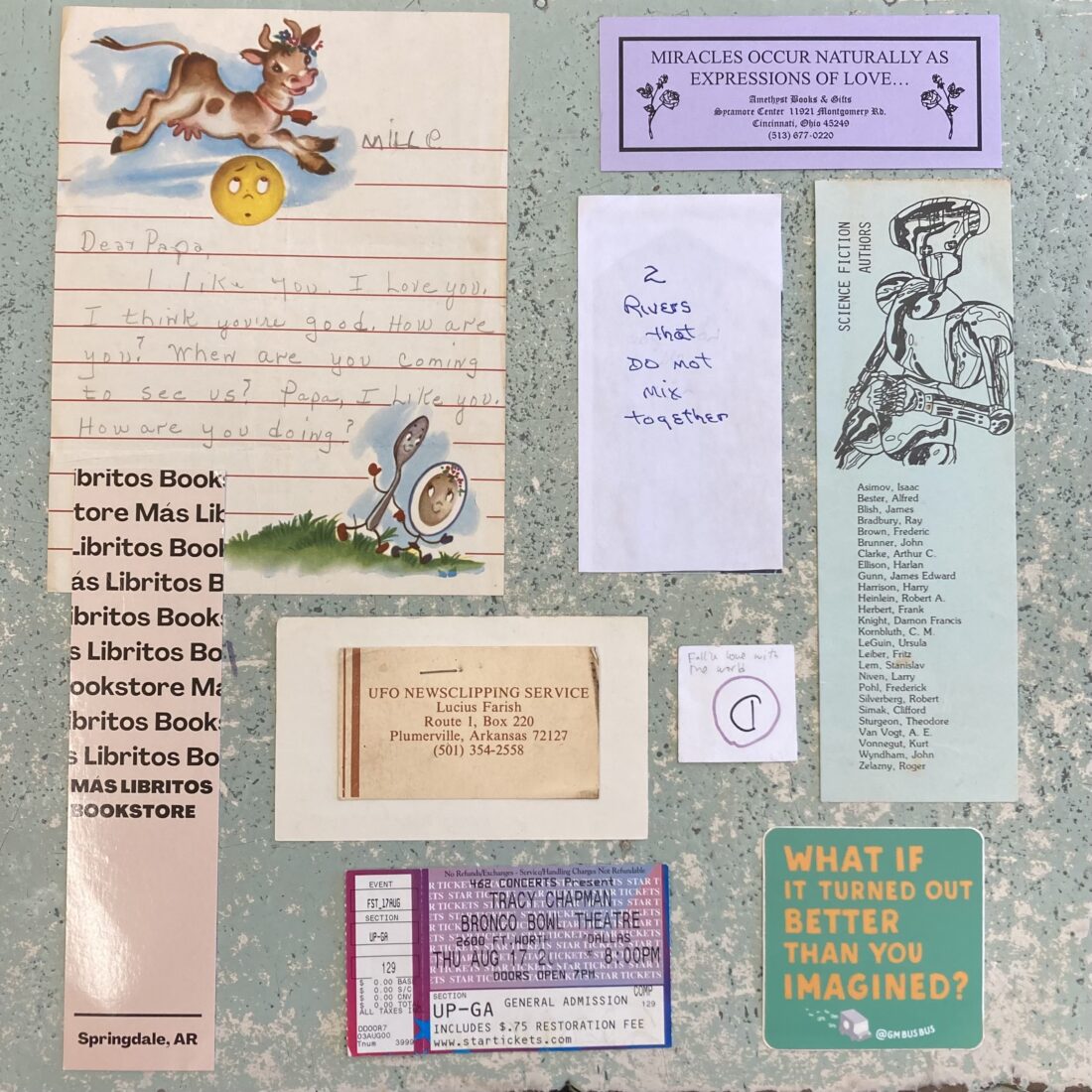

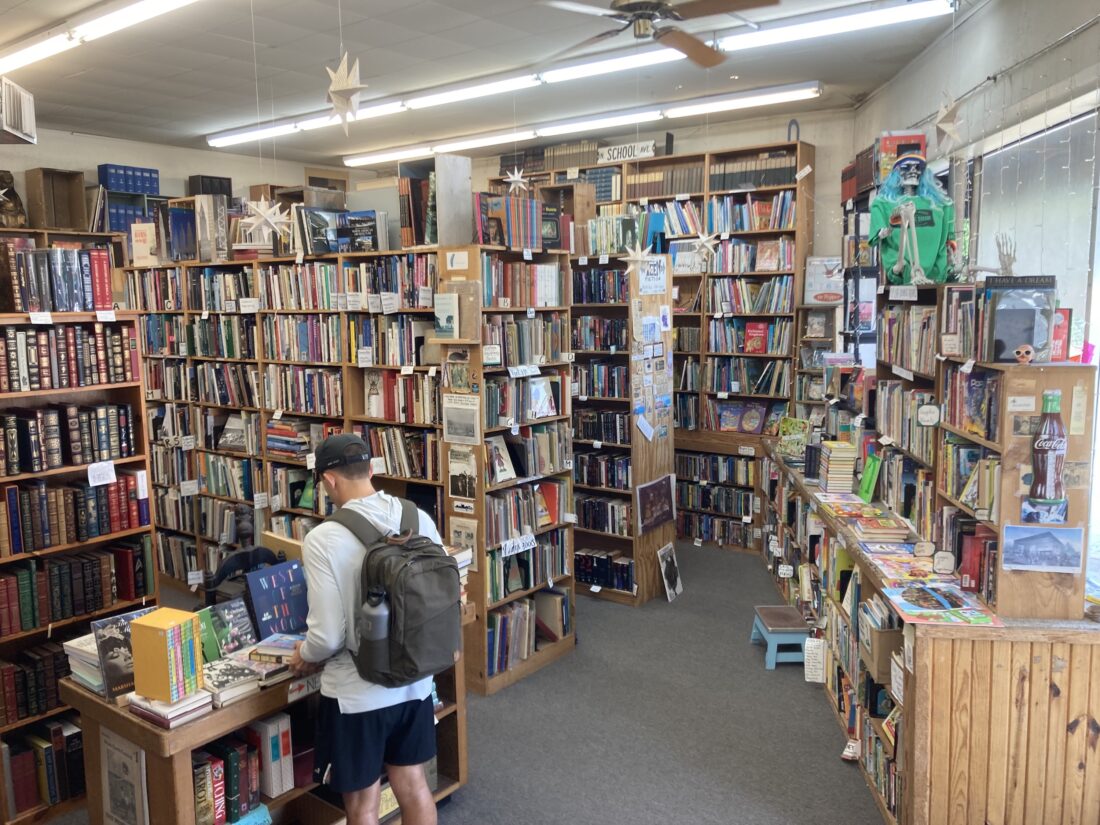

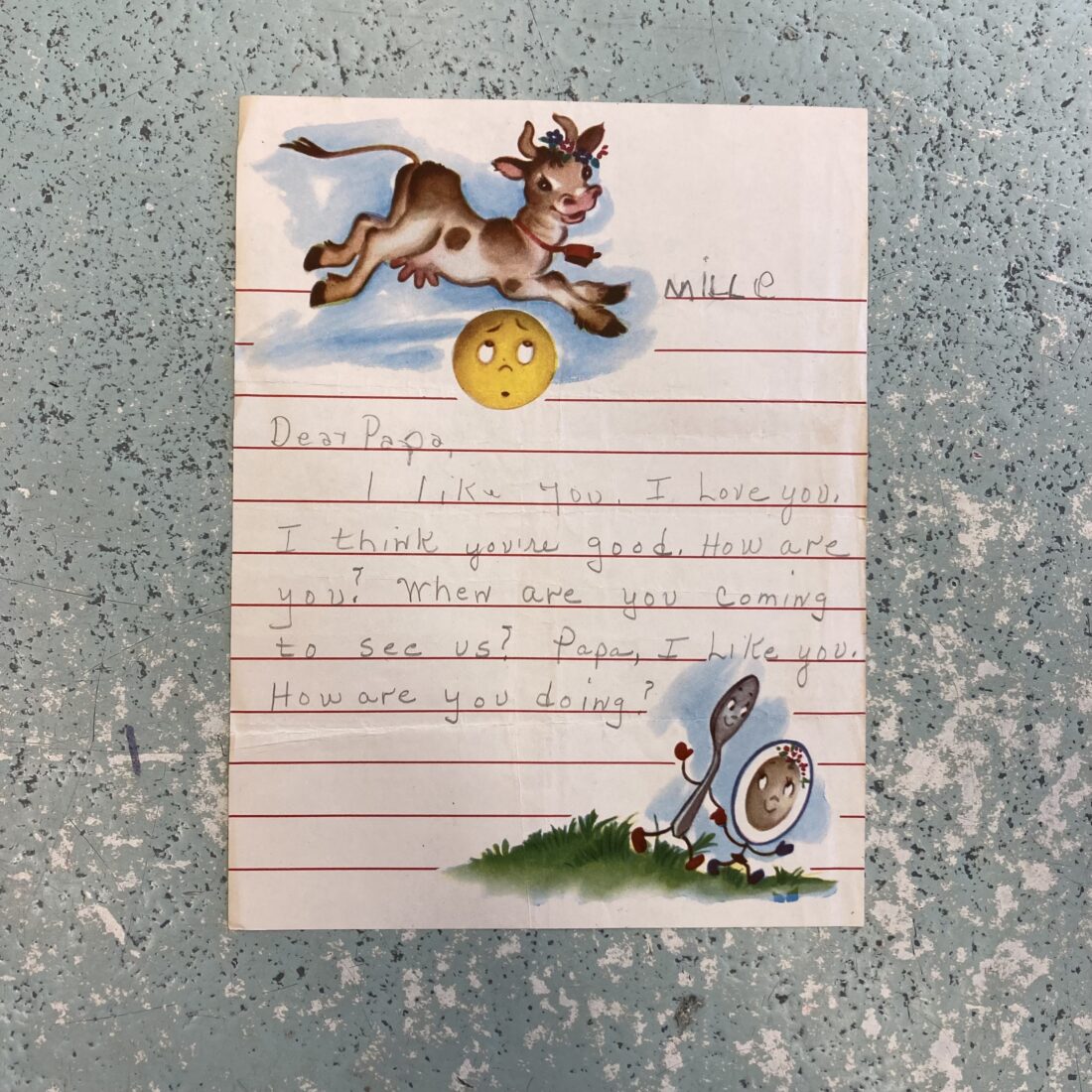

A few months ago, something changed at Dickson Street Bookshop in Fayetteville, Arkansas. This is an extraordinary thing. Change is not a frequent visitor to the sprawling labyrinth of ceiling-high shelves and tucked-away nooks that just so happens to be an iconic used bookstore. Dickson is a place where receipts are written out by hand, where the hundreds of thousands of books that comprise the inventory are tracked through a system of paper scraps scribbled down at the register. And yet. Recent visitors might’ve noticed something new just below the counter: a small wooden box with small plastic-wrapped packets of strange ephemera. Personal correspondence. Ticket stubs. Cocktail recipes. The label on the box reads: “Things Found in Books.”

If it wasn’t already clear: These are the items people have left behind in books they’ve sold to Dickson. They are forgotten things. They are lost things. They are misplaced things and discarded things. They are nightstand things grasped at blindly just before the light clicks off. They are the first thing that came to hand. Above all they are things that have been, by some strange transference, some strange alchemy, saddled with stories seeking to explain how they got here.

But this small wooden box is just the tip of the iceberg—the equivalent of one page torn from the Encyclopedia Britannica—when it comes to objects found in books.

For the rest, you have to enter the back of the shop.

It’s a curiously appropriate flourish that Dickson’s storage areas should have a beyond-the-looking-glass quality. The back of the store is a mirror image of the front, albeit one warped and clouded and seemingly moldering. Every section in the front has its counterpart in the back, with copies of “new” books waiting to replace those that have sold, relying on a system that is, like so much of what you find at Dickson, the product of habit, routine, and inertia.

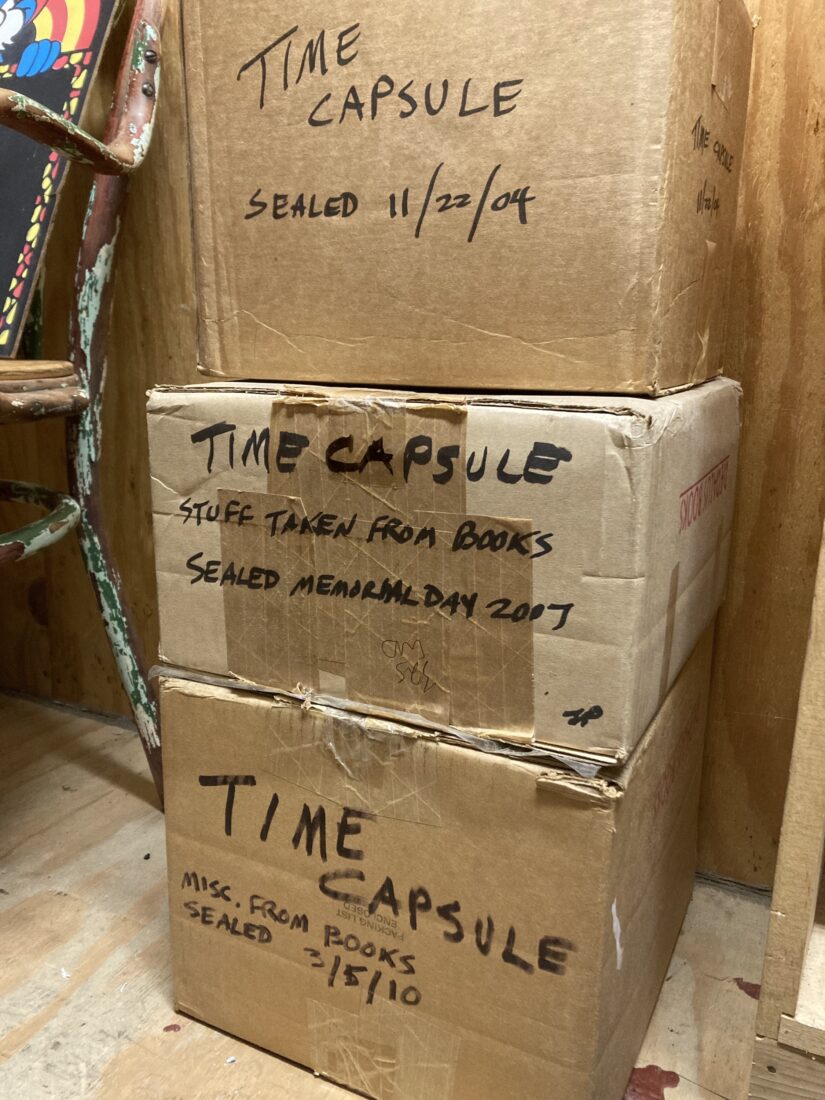

The sole difference—beyond the occasional oversized Gone with the Wind poster and vacuums of varying vintage—is that there are more books, more boxes. And, of course, the time capsules. If you dig long and deep enough, there’s a chance you might stumble across one. They surface periodically, like a wooly mammoth frozen in a glacier, appearing behind, say, multivolume treatises on U.S. history, as boxes get shifted around, books, processed.

They are no different from the multitude of other boxes in the back of the shop, which have been stacked into walls, mountains, and shelving for other boxes (“cheaper than furniture,” says employee Kevin Kelsey). That is, save the words “Time Capsule” written in Sharpie and the date when it was sealed. There are no hints as to what they might contain, but a chance conversation with longtime employee John Peel, who was pricing books on a recent morning, hours before the shop opened, offers some insight.

“You want to see our box?” Peel asks. “There’s a little one right down here. This is where we pitch stuff that comes out of books.”

At his sandaled feet, a cardboard box brims with papers, no bigger than a large shoebox. From the top layer of papers, he pulls a sampling of what he’s discovered recently:

A Post-it with one word scribbled large across it: “Excellent.”

A handmade note informing Judy that “this book was not as ‘readable’ as I’d hoped.”

A birthday card wishing “Sid” a happy fiftieth birthday.

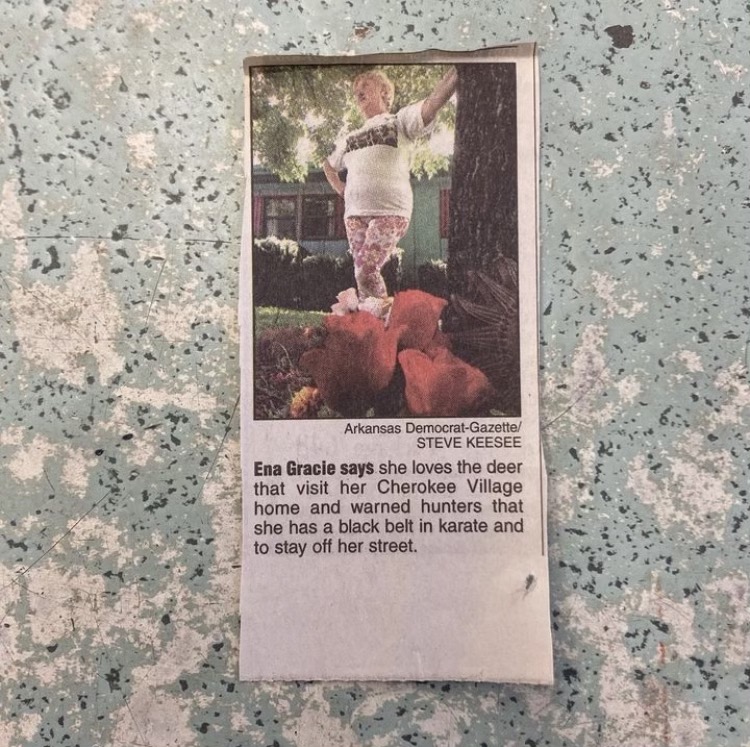

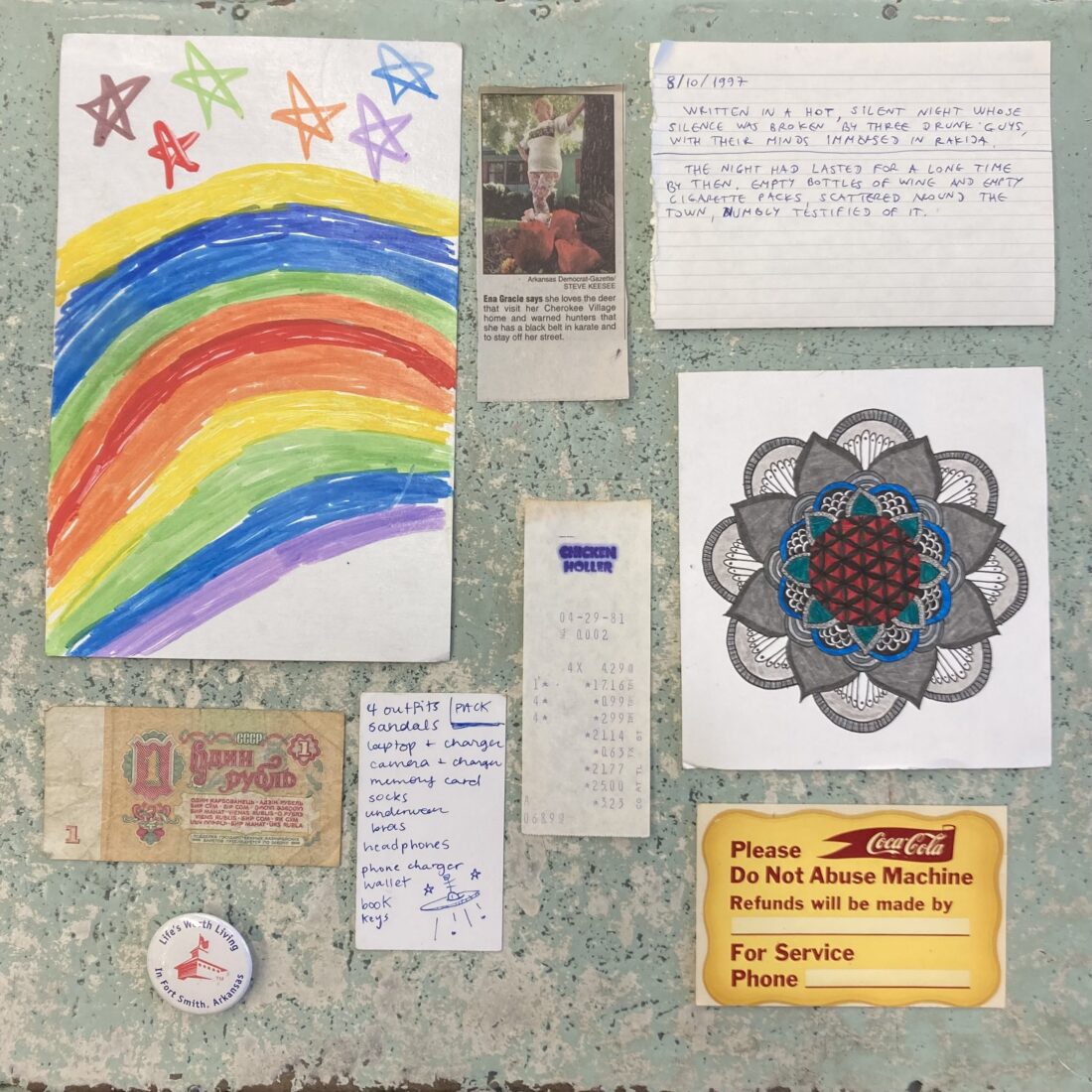

This small container, holding the product of nearly a year’s worth of collecting, is the beginning of yet another time capsule. For more than thirty years, as untold numbers of boxes have entered Dickson, Peel has undertaken a subtle act of curation as he’s priced books to be sold to customers, filling cardboard boxes with an impossibly eclectic range of items that even the most exhaustive list can’t capture. (If pressed, however, you might mention: a Netflix envelope with a Jimmy’s Hall DVD. Imitation Confederate dollar bills. Marijuana. A birth certificate—which was later returned to its very grateful owner.) And then, when a box is filled, he tapes it up and begins another.

Eventually, some twenty years or so in the future, the Dickson staff will gather around the box. And they’ll open it to see what sorts of items people were leaving in books in 2023—whether anything can be gleaned about the habits and proclivities of readers. But it seems unlikely that they’ll be surprised by anything. At this used bookshop, they’re privy to a cross section of socioeconomic forces that aren’t immediately evident to the average person—when people are moving out of an area, say, because housing is becoming too expensive, they’re often offloading their books. And while it’s not time for them to open another capsule yet, found-object aficionados can get their fix by buying packets of the ephemera for $2.95 or by scanning the bookstore’s weekly Instagram posts featuring the objects, curated by Kelsey.

In the meantime, one thing becomes clear as you walk through Dickson Street. As you hear stories about the ways in which the space has changed over the years—about the “fur room” from when the building was a laundry back in the 1940s; about the collage of cut-out magazine pages from when part of the space housed a lesbian club in the 1980s—you understand that the entire store is very much a time capsule in its own right.