The fuel gauge on what Randy Burns calls the Midnight Rider, the dark blue 1945 Stearman berthed in Moontown, Alabama, has sprung a leak. Since the plane’s been in the hangar for the better part of two years, it’s not a huge surprise, but it’s complex, because everything with these planes is complex. A Stearman is an open-cockpit biplane whose fuel tanks are in the upper wings. The fuel gauge isn’t a dial on the instrument panel; rather, it’s a heavy transparent plastic tube, yellow with age, dangling from the underside of the wing tank. The fuel itself bobs up and down in the gauge, not far from the forward, or student pilot’s, cockpit. In other words, above where I sit.

It’s shocking that Burns has even gotten the Midnight Rider’s vintage nine-cylinder Lycoming engine to turn over, not to mention that he’s coaxed it to life to taxi the hundred yards to Moontown’s fuel pump. He cuts the throttle, and with a resounding, gargantuan old-man fart of blue-smoke backfiring, the Midnight Rider stops.

“Been a long time since we heard that Stearman cranked up out here,” says Harold McMurran, the laconic eighty-eight-year-old lead restoration mechanic at Moontown Airport, standing safely off to the side.

“You’ve got a long life ahead of you, Harold,” Burns says, grimly eyeing the fuel drip, “so you just stay over there. We don’t want you hurt when this plane blows up under us in the next couple of minutes.”

“What do you reckon,” Burns says to me.

It’s a suggestion that we move smartly on the leak. He grabs his pliers, I fish an empty Gatorade bottle out of the garbage, but it won’t reach the gauge, so we stand the bottle on an upturned Hardee’s big-slurp cup. With our super-high-tech fuel-retrieval system in place, Burns starts trying to tighten the gasket and secure the gauge.

Photo: Eric Kiel

High Flyer

Randy Burns in front of No. 43, aka Yellow Peril

We can’t fly with the leak for a few reasons. A central precept of manned flight is to keep the fuel in the tanks or in the lines leading to the engine, as opposed to blowing around in or outside the plane. Second, we don’t know what the leak will do in the hundred-mile-an-hour wind the gauge will get, but the cockpits are directly behind it, and it’s a great disadvantage to try to fly with leaded aviation gas misting your face. The long-term reason is that a Stearman is made of fabric stitched over a wood-and-steel frame, and the fuel will eventually etch at what the pilots call the dope, meaning the many careful layers of paint over the fabric, and then will weaken the fabric itself.

“Let’s get out of here,” Burns says, wrapping it up.

Like a tethered falcon with a blindfold on, a Stearman makes almost no sense on the ground. It was designed as a pilot trainer for the U.S. Army Air Forces and the Navy before and during World War II. The cockpits are tandem: Instructors sit in the rear and the students forward, but since it’s a taildragger, and the fuselage is canted back with the little wheel under the tail, neither pilot can actually see over the nose or the engine when the plane’s not flying.

So the trick is, Stearmans have to be taxied in a constant S-curve, with pilots hanging their heads out one side, then the other, as whatever’s in front of them becomes visible over the cockpit coamings. It’s worse than ungainly, but that’s what we do as we bounce along the grass to the head of the airstrip.

Moontown—known to pilots as Moontown 3M5—has just the one two-thousand-foot grass strip, a fescue meadow with a gully at its head, a wind sock in its middle, and a cotton field at its foot. The standing ashtrays flanking the salvaged-church-pew “smokers’ bench” on the runway-side porch are surplus World War II bomb tail fins with tin cans on top. Moontown is what a grass strip ought to be—it’s what they have been for the last ninety years in Alabama: a field tucked somewhere in the farms, a ready room with some beat-up chairs, a huge humming coffee percolator, a rack of salted peanuts and crackers in old-school cellophane, a bunch of T-shirt fragments with names and dates scrawled over them nailed to the walls, cut off the backs of the pilots who first soloed there.

Moontown is by no means the funkiest of the dozens of grass strips in my part of Alabama. That award goes to the runway of Madison County farmer George Epps, a few miles away. Epps has helpfully lined his runway with whitewashed used tires laid on the ground. But let us make no bones: To be able to walk fifty years straight back in time and to be able to work early- to mid-twentieth-century planes, on grass and in the air, Moontown is the joint. It lies in some farmland about twenty miles north of the Tennessee River, in Brownsboro, Alabama.

Burns cranks up the rpms. The plane scampers down the runway and quickly does that hunting-dog thing that taildraggers do, lifting its tail first to level. Then it shoulders up into the air. He arcs it over the cotton, and we’re bound north, then turn east, and hit 1,500 feet.

There’s no catch in the engine; it’s running well. I know this because my seat is three feet behind the Lycoming and I can sense every knock and whistle of that monster in every muscle of my back and legs. This isn’t in a lot of flight manuals, but one’s ass is a crucial sensory organ for antique biplane flight. It’s no joke to say that, in these planes, you fly by the seat of your pants.

Photo: Eric Kiel

A plane’s cockpit

The point is, everything in a Stearman is supposed to be felt. The plane is all manual, stripped down, tight; as Burns puts it, “You pull this plane on like a pair of jeans.” There’s no “deck,” just a couple of metal tracks for your feet and the pedals—when you look down, all you see is the stick, some airframe, and the fabric covering the bottom of the fuselage.

I’m off the controls but can follow Burns’s moves through my pedals and my joystick as we bank between the hills and climb through the bumpy summer thermals over the ribbon of the Tennessee River. We’re running east along the river over some more cotton.

“See the road to the right of that barn?” his voice crackles over the headset. “We could put it down there if we had to. Gotta always be looking around for what to do when things get busy, because when the moment comes, your planning time will disappear.”

Things getting “busy” is Burnsian code for in-flight trouble, of the foolish man-made or of the big mechanical sort, forcing a landing pretty much anyplace but a swamp. Right this second we’re riding a cobbled-together sixty-five-year-old plane that hasn’t been out in a couple of years, and we’ve just plugged the fuel gauge with what I think might have been electrician’s tape, so reckoning that things might get “busy” is a good way to think. But beyond this, Burns has a special gift for flying old planes, having been taught to fly in a fleet of craft by his pilot father and his pilot mother from the age of zero, basically.

Burns and I have been friends for a decade. We share pilot fathers. We were introduced by my father and his friend and flying buddy Clay Smith, the late longtime manager of the strip next to my hometown of Athens, Alabama, from which my father flew as a teenager and where Burns now keeps two Stearmans. Burns, a cardiologist by day, has most generously taken me, a rank novice, on as a kind of Fresh Air Fund charity project to teach me the dark arts of flying really old planes. These are the planes my father, and his father, flew. I’m not very good—I’m working on it—but I’ve flown enough with Burns to know that he practices the 360-degree-awareness school of aviation, in which there is just one real rule: Look at your plane, look at what’s above, below, behind, and around you, and never stop looking at or thinking about any of those things.

Which is why we’re doing this ride—Burns has been asked by this plane’s owners, both of whom are getting on and thinking of selling—to take her up for a baseline workout. Like a polo pony, the thing’s got to be ridden. We push the Midnight Rider over Highway 72, which is the grand old east-west road that parallels the Tennessee River across the northern tier of Alabama. We’re only going about ninety mph, unkinking the plane’s muscles, stretching its legs, taking a breezy run. Burns is checking the fuel mix, acceleration, and trim. After some lazy turns from the highway to the river and back, it’s time to take this big girl back in.

Landing at Moontown is a country-boy job of work, no matter what the plane. We come in from the east, drop over some soybeans, drop to a hundred, then fifty feet over Moontown Road. I love these times of ushering an aircraft through a change. I happen to think that fifteen to twenty feet off the grass is always an illuminating place to muse on the many ways that this next, imminent meeting of you and the real earth can work out.

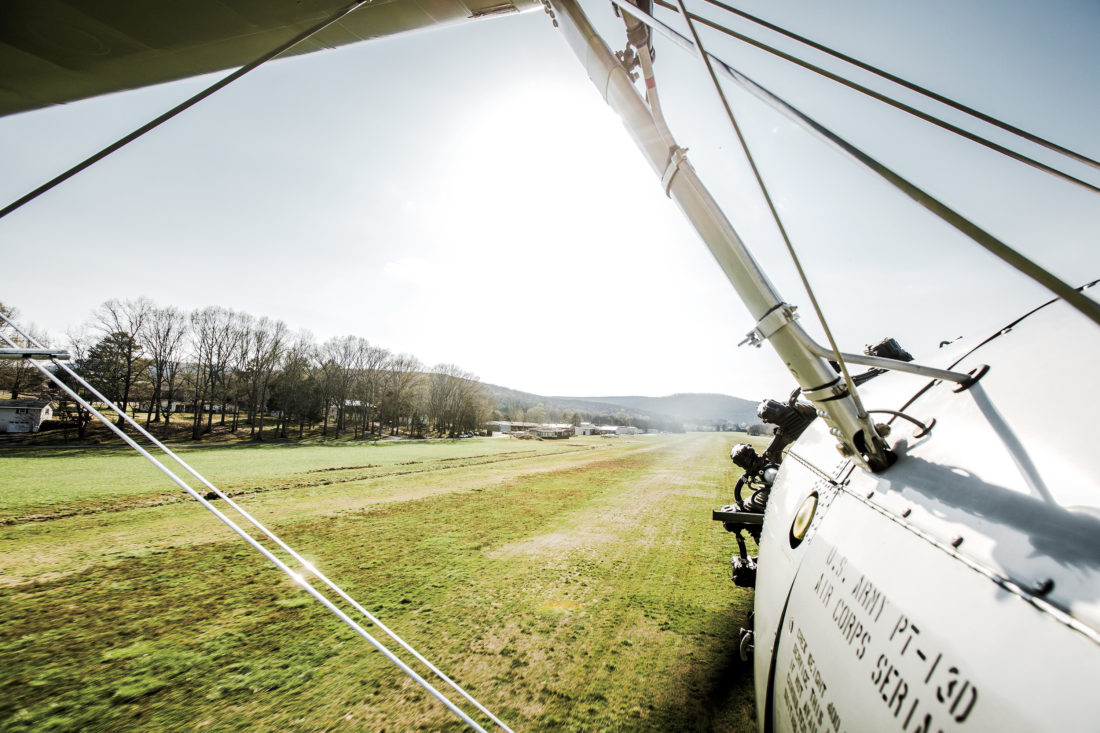

Photo: Eric Kiel

On the Wing

A Stearman comes in for a landing

Burns throttles down with a tender touch—I swear the man could fly a dead dog, whether or not it was on its way to heaven. The plane doesn’t fall so much as it lets go of the sky. He eases back on the stick, the nose comes up a little, the main gears bounce and settle, the tail floats down at last, and here we are in Alabama, between the soybeans and the cotton, rolling along on a soft, wide sea of grass that slaps at the tires.

In High Cotton

Like many stories in Alabama, the story of this sort of flying begins with cotton. In 1849, forty years after its acceptance in the Union, Alabama led the nation in cotton production, with 22 percent of the national crop, largely bound for English mills through Mobile and New Orleans, and worth billions. The two great bands of cotton in the state were—and still are—the Tennessee River Valley in the north, and the Alabama River farmers in what is called the Black Belt. Of these, the farms in the north were the more productive, the land flatter, the dirt redder. There was cotton everywhere. In my childhood, my home county, Limestone, produced the most in the state. The white, billowy detritus along the roads after the harvest was called “October snow.”

By the early 1900s, the boll weevil, a cotton-eating Central American parasite, had migrated up from Texas and attacked Alabama’s money crop. Almost to a man, the cotton farmers turned to early-form pesticides, which were strewn, ineffectively, by tractors. It was only a matter of time before the Wright Brothers’ nutty contraption, the airplane, met the agricultural need. By the 1920s, crop dusting had been born.

World War II changed the course of things in the Tennessee Valley, and most certainly in my hometown, Athens. With the Nazis’ aerial assault on Britain in 1940 and the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, the U.S. military realized that the coming huge air war would require a maximum number of pilots and a lot of clear weather for training them. They looked south. Hundreds of fields were hewn into the farmland, from Georgia out through Texas to California.

Among them was Pryor Field, stuck in a cotton field on the Pryor Farm in Limestone County, twelve miles south of my hometown. Five hundred workhorse Stearmans were stationed there from 1941 to ’45, graduating some two thousand pilots. Too young to fight, my father, Richard G. Martin, Sr., was a “line boy” at Pryor Field during the war.

Line boys—so called because they readied planes for the flight “line”—towed planes, gassed them up, tied them down; they were the subaltern Oliver Twists of the airstrip. My father was a little different in that, at seventeen, he had his pilot’s license and had bought a small single- engine Taylorcraft that he kept at a different strip not far from my grandparents’ house. So he flew the twelve miles to Pryor Field and back, every day. The Taylorcraft had no radio. Still, his Taylorcraft was better than the Taylorcraft he soloed in, which had no brakes. When taxiing that plane, you braked with the throttle. Or, you didn’t.

“I used to land my Taylorcraft on the outside edge of where the planes were tied down, right next to the hangars,” he explains, “until they told me to stop because I was getting too close for their comfort to the planes. I thought it was a good idea because it kept me off the runway where the training was.”

Photo: Eric Kiel

Moontown regulars take a break between flights

He landed on a skinny little bit of concrete. The slab is still there today at Pryor Field, with a few weeds poking up through it, along with the World War II maintenance hangars that he worked in, which are also still in service.

On Victory in Europe Day, as the German General Staff surrendered, Daddy took his Taylorcraft up over the courthouse square in Athens to play “tag” with his flying buddy Will Clay, who had a Piper. As the boys chased each other around the copper dome, a crowd gathered, and my grandmother Vashti, who had been in town shopping, saw the ruckus, recognized the plane, went home, ordered tea, and took to bed. The sheriff called Pryor Field to get them to stop, but the boys had no radios and couldn’t be ordered down.

My father prefers now, in his mid-eighties, the gentle art of self- deprecation. “I don’t recall that we were ever really in danger of actually touching wingtips,” he explains over drinks on his porch. “It was more of a fake dogfight. We were just flying around the courthouse because it seemed like the thing to do. I was in it for the speed.”

With the demobilization of Pryor Field in 1945, the five hundred Stearmans then stationed at the field were sold to the highest bidder, and the great dispersal of the planes began. That fall, all sorts of prevaricators, jackanapes, and aviation entrepreneurs who thought they could make a buck were after the surplus. The most far-flung order came from some American expats in South America—they wanted a half dozen of the Pryor Stearmans, and part of the deal was that Pryor Field had to deliver them to Miami. My father and five other pilots ferried the planes to Miami, a two-day barnstorming expedition across nine hundred miles of Deep South. They set out on July 8, 1946. He was eighteen.

“I have no idea what those boys in Colombia wanted with them, gunrunning I suppose,” he muses. “Our job was just to get ’em to Miami. But as to the trip, I remember that none of us had radios. Jack might have had one. None of the rest of us did. I know I certainly didn’t.”

No radio, I say. I’m grappling with what that means over nine hundred miles in the air.

“No. So when we stopped in Atlanta to gas up, for instance, we had to circle the field a couple of times to make sure they noticed us, and then you sort of assumed permission to land.”

Photo: Eric Kiel

The dual cockpits of Yellow Peril

Atlanta, I say. Hartsfield Atlanta.

“Didn’t have any charts, either,” he says, “or maybe somebody had one. Again, I didn’t.”

I ask him if there was a compass on his instrument panel.

“Might well have been,” says my father, “but, you know, it’s fairly simple to get to Miami. You just fly east over Georgia, and when you hit the beach, turn right. Now, flying down the beach was quite a lot of fun. The weather was warm, and people were on vacation, so we’d fly low and do rolls and all kinds of tricks for them. And they’d stand up and clap and whatnot. Some of us flew the length of Florida mostly upside down.”

This is the snapshot of America’s postwar exuberance, then, in July 1946: six rangy-ass Alabamans jiving and tumbling in a formation of bull-nosed Stearmans all the way down Florida’s long side. It also provides us with the exact moment in American history when the swords of the air war, so to speak, were turned into commercial plowshares. Latter-day Butch Cassidy–expat gunrunners aside, by far the more common fate for the Stearmans of Pryor Field was to wind up as crop dusters. The chemical tanks could be fitted into the forward cockpit, and the steady muscularity of the Stearman came into good play as the acrobatic dusters needed to pop up over tree lines and skim in low over the fields.

Exactly that was the fate of No. 68, a Stearman sumptuously restored by Clay Smith, my father’s childhood friend. Smith’s sons run the field to this day. No. 68 was a noble workhorse at Pryor that found its way into crop-dusting service in Texas after the war, where Smith tracked down its ragged hulk, bought it, brought it back home to Athens, and restored it to literally national renown. No. 68 won first place in the annual Oshkosh, Wisconsin, competition for restoration in 2006 and now resides at Pryor Field, one of the few World War II–era Stearmans in the country still flying from its original base.

No. 68 now leads a retired Thoroughbred’s life, making appearances at local festivals, and can be booked for rides, but the narrative the plane represents is somewhat greater. Seventy years on from their manufacture, long past their war and farm lives, these Stearmans are now exalted collectibles in exactly the same places where they worked, namely, the South, because of the sun, because of the dirt, but mainly because of the fliers who loved them, grew old with them, and never let them go.

To Fly or Not to Fly

Many of the aviating families in my part of Alabama are connected, so it’s apt that Ken King copiloted with Randy Burns’s father on many cross-country flights back in the day. These days, he is the very level-headed master responsible for a large portion of the cut-up “solo” T-shirts nailed to the walls at Moontown. He’s currently teaching Randy Burns’s son Charles—in other words, his old flying partner’s grandson—and when I’m at my father’s house, me.

Of the three aircraft available for lessons at Moontown, I vastly prefer the oldest one, a vintage Champ, a tiny two-seater with a homey, aw-shucks quality. It looks like a little yellow dragonfly with its red belly and its snout up in the air. You feel like you could keep the Champ in your backyard, and if your house were on the right road, you could take off from your doorstep.

“This plane was built in 1946, so I like to say that it’s eligible for its Social Security check now,” says King drily as he pops open the engine cowling and gazes around at what I at first think is a converted lawn mower engine, until I count the spark plugs and realize that it’s somewhat bigger. A Moontown mechanic, most probably Harold McMurran, has left a helpful note written directly on the exhaust manifold in Magic Marker (caps and lowercase his). It reads:

4 qts. Max

Add Oil when

below 3 qts.

I’m pondering this note as King wrestles with one of the set screws on the panel that won’t thread into its place for the flight. We, or rather I, very much want this somewhat floppy sixty-seven-year-old engine cover to stay shut during the flight. King would want the same thing, but he’s so splendidly cool that I believe even if the panel came off, pierced the windshield, and chopped my nose off, he would say something like “By the way, if you find that piece of nose, put it in your pocket, and we’ll have you down in a second where they can stitch it back on. Might even look better than it did.”

Photo: Eric Kiel

Flight School

Ken King, the dean of Alabama flying instructors, at Moontown

King pulls a quarter out of his pocket and screws the panel down tight.

“Well, I thought today we’d just do some stalls and turns and shoot some landings,” he says affably.

For all its Morris Minor tininess, the Champ is quite agile. I’m always chintzy with the rudder, a bad habit, but I manage a few clean turns keeping the nose on the horizon before King takes the controls and says, “Okay, let’s take it up and stall it.”

With that he climbs, and climbs, and the engine works harder and slows down until the plane starts sliding in an ugly fashion back in the air. By forcing this stall, King is consciously bringing the craft to the point in the trigonometry of flight at which the math just won’t work anymore. In its fall, the Champ noses a bit to the right. Of course, we’re still in the air at 1,200 feet right over Moontown, so there’s plenty of room between us and the ground for us to do the work of bringing the plane back to where it wants to fly. Which King does in short order by simply putting the stick forward—in other words, ensuring that the plane will dive, so that the wings will have a chance to bite the air. The engine gets happier because it isn’t pulling so hard, and we’re flying again.

“Feel that?” he says.

“Yes sir.”

It’s counterintuitive, but the logic is, you’re headed down anyway, so you want to control that, and then level off. It’s about learning how to recover in case a stall “happens.” Truth is, stalls never actually happen. They’re caused, as when JFK Jr. lost the horizon in his plane off Martha’s Vineyard and couldn’t recover.

We stall three or four more times. It has a certain giddy fun—and it’s useful at the upper professional levels, like having the plane do a stutter step, more or less.

King talks me through the descent, and I think I’m doing fine, but as we cross Moontown Road and meet the strip, it turns out that I haven’t descended at the right rate, and we’re high. It’s a bad thing because you run out of runway before you know it, so King hits the rudder, skewing the plane to the left.

“Just comin’ in a little high, Guy. I thought I’d put it in a slip,” he says quietly.

I don’t understand what he’s done, but the plane is pointed toward the ready room, and it feels like we’ll just do what the old pilots call a “ground loop,” meaning, hit a wing and flip over. We fall to thirty feet, King lets the rudder go, the plane noses straight instantly, and we touch down as if guided by a wire.

I’m thinking about the elegant vocabulary: the slip. Give it the slip. There are many kinds of slips, but what an aeronautical “slip” does is exactly that: It helps you exit the process of flying for a second so that you fall faster, and then allows you to reenter the process of flying when you’re better situated. In the unforgiving stylebook of flight, a slip is a parenthesis, a stall is a bracket. I don’t ordinarily think of Alabama as a capital of Zen precepts, but the Zen-like lessons of this day at Moontown, in Brownsboro, Alabama, are about figuring out what it means to “not fly” for a few seconds. In order to better grasp how to fly.

Photo: Eric Kiel

A student’s-eye view of cotton country

Toward Home

I keep thinking there might be a way for me to get Randy Burns a national talk show with me as his sidekick, but then, all the guests would have to be flying with us and the production costs would be huge. So many planes in the air at once, and it’d be tough to ferry the guests from one to the other in midair.

Here’s where Burns and I are, and how we are, in the air at the moment: Burns is off the stick and I’m on it in the bright yellow 1941 U.S. Navy Stearman PT-17 belonging to his family, which is to say, he’s “talking” me through this bit. The history of the plane matches the moment very well, I think. In training the Navy boys during World War II, this particular Stearman was known by the instructors as the Yellow Peril, an insulting nod to the Japanese enemy, of course, but mainly it was a wry professorial insult to the flying abilities of the students who were in the planes. The planes were not painted yellow by accident—everybody from the ground crew to the controllers wanted to know where these planes were at all times. The broad red stripes down the wings, which, with complete historical accuracy, Burns’s PT-17 also bears, meant: a really bad novice pilot. This is just to say that if there were ever a student pilot who deserved every last bit of the warning paint on this plane, it is I.

Luckily for me, the Burnsian 360-degrees-of-awareness school of aviation has a sound track beyond the roar of the engines, depending on the planes and whether they’re wired for headsets. The Navy Stearman is wired for headsets, so here’s approximately what I’m getting:

Look up! (Static.) You’re not looking up, remember you’re in front, not me, okay good. Altitude? Altitude? You’re climbing without knowing it, don’t get above two thousand. So now, what kind of fields do we see WITHOUT POWER LINES where you can put this thing down without killing us? (Static.) Please. And okay, we’re two miles out, looking out now REAL GOOD for stuff coming off the runway at Pryor, you can never tell what they’re throwing up in the air, might even be some kind of idiot in a jet…(Static).”

We’re flying over Limestone County, my home. The view that I have from my cockpit of the Tennessee River and the flat cotton land south of town would have been one that my father had in his Taylorcraft en route to Pryor Field seventy years ago.

To look at your home from above, as I do every time I fly out of Pryor with Burns, is a way of seeing it new and seeing it old—there’s the courthouse my father flew around, there’s Old Highway 31, there’s my great-grandfather’s house, my grandfather’s house, there’s Daddy’s, there’s the river, there’s the cotton. Flying in these machines, I’m in a time machine in every way. My life is on the ground and in the air.

We have a small oil temperature problem with the yellow Stearman today—it’s midsummer, it’s Alabama, so the temp’s running a little high. We’re watching it as we work out over the river and do some turns. Today is also about a landing back at Pryor. Pryor Field’s main runway is paved, so that, unlike my father, when we land there these days we prefer to land precisely on the grass in the sections between the ramp and the runway. They keep it mowed for that reason.

Photo: Eric Kiel

A cold-weather Stearman

We circle back over the big river and head north. The notion is to get a mile or so north of the airport and then come around and land heading south. The wind’s a little pocky, what with the summer and the river, making it hard to hold the descent steady. We’re at five hundred feet, then three, then two.

Burns is silent. At a certain point, he’ll take over the controls. But not yet. He wants to give me the moment to feel it, feel the air, feel the descent, feel the plane in my bones as it is doing this thing.

Burns says, “Hold what you got, hold what you got, hold what you got.”

By which I take him to mean, with the cotton to our left and the grass fast approaching, my view of home.