There’s been a lot of hoopla recently about “eldest daughter syndrome.” The conversation about the burdens and expectations taken on by firstborn girls came to a simmer on the internet and within days boiled over into mainstream news. I noted the topic, but never clicked to listen or scroll to read more. The headlines told me everything I needed to know: This was one syndrome I didn’t have to worry about. I’m the youngest of four.

That makes me a forty-six-year-old baby. Full-grown but never fully formed in the eyes of kin, babies of the family have baggage too. I would even argue that if the eldest sibling carries more of the familial burden, the youngest shoulders more of its blame. In fact, we barely clear the womb before we feel the effects of kicking the family’s current baby to the middle curb.

For me, that happened even earlier: in utero. My mom was thirty-nine and steroid dependent due to rheumatoid arthritis, so my parents—and my three siblings—weighed the risks of bringing me into the world. Ultimately, my sisters were asked to cast a vote. Currie, then the middle child, voted “no,” citing concerns about how the farm would be divided with another daughter in the mix. Leraine, the oldest, voted “yes” to a new thing to worry over, and Johna, the reigning baby, voted “no” for personal reasons.

Johna had good instincts. As soon as I grew out of my crib, I moved to a twin bed next to hers. At age four, I loved ripping off my wet diaper to the sound of Guns N’ Roses and the smell of Aqua Net in the morning. Johna, age fifteen, didn’t return the joy.

I recently witnessed a more traditional baby dethroning when my great-niece lost her crown to a newborn. It all went down as if we were watching a live Bravo reality show, with lots of wailing, feigned sweetness, side-eye, and the occasional scene where the lead loses her will to walk. Regardless, the baby’s arrival would have wreaked havoc sooner or later, and despite the presence of parents, what I have learned is that it ultimately falls to the baby herself to restore familial homeostasis.

This is why, I believe, that when you Google “common traits of youngest children,” you’ll find over and over again that we are incredibly charming. We have to be.

I can’t quite articulate what it felt like to be a baby thorn in my siblings’ sides. I was an infant, after all. But I can tell you that I’ve always been very aware of people’s moods. If they are good, I’m good. If they are bad, I leave. If they are somewhere in between and I think I can push them over the edge toward happy, I entertain.

When I was a child, that took a number of forms. On Christmas morning, for instance, I would throw myself on the floor and writhe around in delight at the sight of the Weebles house I had asked for. Or I opened and then abruptly slammed the foyer door and threw my hand over my gaping mouth to show I was more thrilled to have gotten a fake Cabbage Patch doll than the real thing.

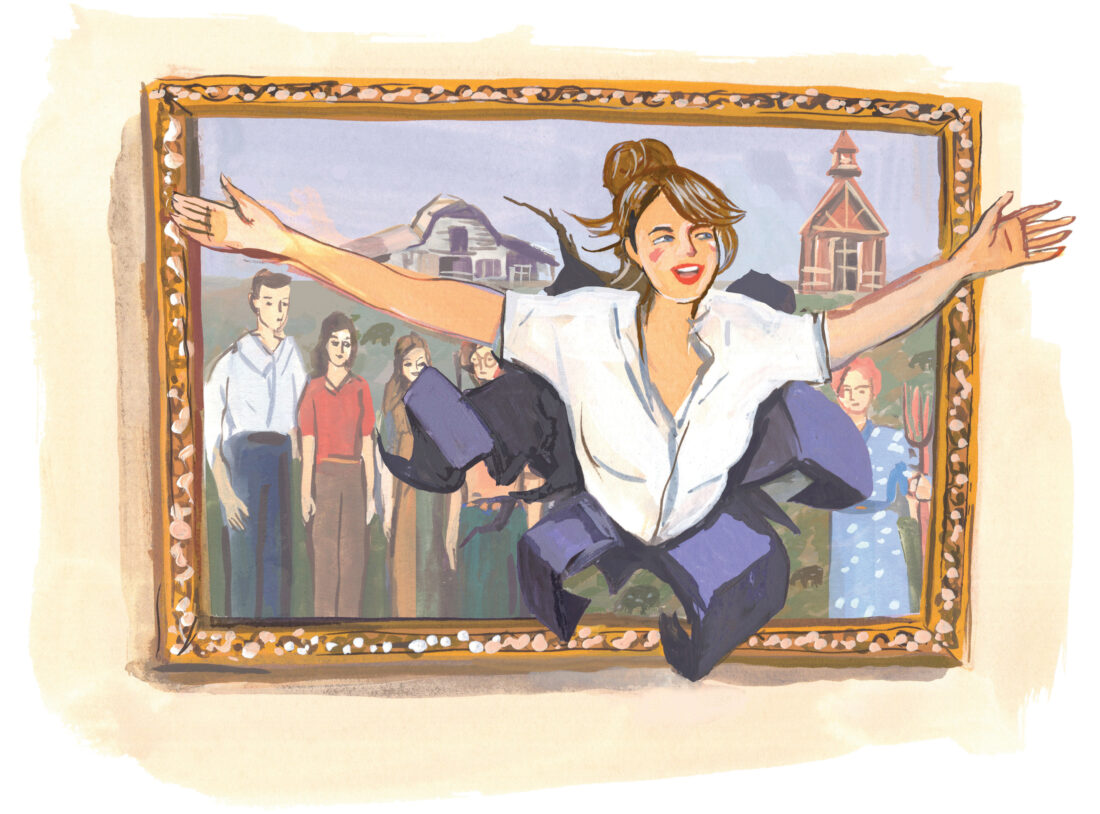

As I got older, I discovered the power of making people laugh. Not always the right people. When I announced to the entire breakfast counter at the local café one Saturday that Currie couldn’t join us because she was on her period and as ill as a snake, I got a load of laughs from my audience. At home, Currie hurled her ham biscuit at my swollen head when she heard. In boarding school, I leaned in to physical humor by dancing wildly for my hallmates. My gyrating, spins, and kicks brought everybody to tears, and I loved the feeling.

Babies, you see, delight in delighting. And I’ve been fortunate enough to do so for the Howards a ton. Not many children, regardless of birth order, get to make a TV show that highlights a family and its culture the way A Chef’s Life did. I knew I had created delight junkies when I told my dad I had just won a James Beard Award for best TV host, and he asked me what else I could win.

Youngest children also tend to be persistent. I would never identify myself as such, because I feel like I give up on more things than I start, but my sisters claim that as soon as I learned to talk, they all wished I hadn’t. I wasn’t one of those kids who asked, “Why?” a hundred times a day, nor was I particularly chatty. Instead, I got hung up on things I wanted to do or things I felt I needed to have. One of these “wanter” bees would land in my bonnet, and I would talk about it all day. I’d pray for that little bee at night and then go to sleep audibly wondering if God would answer my prayer. The first buzz out of my mouth the next morning was bee related.

Today that persistence manifests itself pretty much the same way. I get an idea as big as creating a shade garden out of the weed jungle next to my guesthouse, or as small as preparing pistachio cream, and I ignore every obstacle or prior responsibility to see it through. That’s why people run for cover when I announce I have a brainstorm. If they stuck around, they would see that about 75 percent of the time, my enthusiasm peters out and little to no damage ensues.

Last borns are also notoriously codependent. We get this honestly, but oddly enough for two different reasons: Either your mom coddled you like an actual baby for far too long, because she loved the snuggly instant gratification that stage of parenting offered. Or you grew up in a household that used to have a lot of rules and systems in place to impart independence, but because the majority of the family could now take care of themselves, it became less urgent to show you how to do the same. Either way, you may not have known how to make your bed when you left home for the first time, and you might need someone to help you do that with consistency until you die.

I am not merely the baby Howard, I am the baby Howard by ten years. That means my oldest sister, Leraine, was in college by the time I was potty trained. Currie was away at boarding school before that, and I’ve already mentioned Johna’s disinclination to invest in my well-being, so I led a choreless, messy childhood with parents who decided they had finished the brunt of their child-rearing and were relying on the ghosts of my well-behaved sisters to guide me.

Luckily, they did instill in me the fear of God, so my upbringing wasn’t lawless. And I learned how to put sheets on my bed and do my laundry as a ninth grader at Salem Academy. But it wasn’t until I was an intern at the Michelin-starred WD-50 in New York that I fully understood the importance of punctuality and how to properly clean up after myself. I’ll never forget the day the chef brought my shortcomings to everyone’s attention. I turned into an often punctual clean freak after that. That’s the other thing about us last borns. We’re quick learners and hard workers. That’s what it takes to be everybody’s favorite.