I recently attended Garden & Gun’s Society Gathering at Hotel Emma in San Antonio. As part of the event, I appeared on a wordy-nerdy panel with fellow G&G columnist Latria Graham and editor in chief David DiBenedetto. We talked about what it’s like to be writers at a fabulous magazine in the fabulous South. It was a pretty wonderful hour for me, blabbering, naturally, and slapping my knee at my own remarks in a pocket of professional banter into which I’d always dreamed of nestling. But after the panel, and actually even before it, several people commented to me about how odd it was that I could both write and cook like a pro. At the time, I let the compliments wash over me and agreed I was indeed unusually gifted. But on the flight home, in that fuzzy place between reduced cabin pressure and a nap, my subconscious piped up and gave me a reality check.

Truth is, I have never really felt like an actual chef, so the thought of sitting on a panel with a couple of real deals of that variety stresses me out. I’ve done it, don’t get me wrong, but each time I stammered, tripping over my words, terrified I might say something to raise the curtain and reveal the plain old cook (not chef) hiding behind it. Yes, I make better food than most people. I have expedited, ordered, scheduled, and eighty-sixed with my tweezers out for two decades and did much of it pretty publicly as the host of a PBS show called A Chef’s Life. I don’t half-ass anything, especially not charades, but if you smell some impostor syndrome skulking around backstage, your sniffer is on point.

While Kelly Fields was rolling out biscuits at her grandma’s elbow and Rodney Scott was soaking up the science of barbecue in his family’s smokehouse, I was going to the backwoods version of Weight Watchers, a.k.a. the Diet Center. It wouldn’t have mattered, though; I had no interest in being in the kitchen with my mom where the dishes got washed. Instead, I made the adults around me happy by straight up entertaining them. Every member of my family loved soap operas, so one of my first and most notorious acts was as Nikki the stripper from The Young and the Restless. Photos show three-year-old Vivian dressed in a bikini, a tiara, heels, and my mom’s pink rayon robe. Later images suggest she took it all off. When I grew out of undressing in front of others, I took to telling stories that made people laugh. And when I got in trouble at home or something didn’t go my way and feelings got hurt, I would retreat to my room and write a little synopsis of what happened from my perspective, always with a few funnies thrown in, of course. Then I’d noisily exit my room, slam the notebook of truth on the kitchen table, and stomp out the back door, only to return ten or so minutes later to a tide turned in my favor and a generally improved household mood.

In addition to what I did and did not do as a kid in the kitchen, my impostor syndrome refuses to overlook the things I do and do not do as an adult professional chef. Like the time I met Mike Lata, of FIG and the Ordinary in Charleston, South Carolina, in the kitchen at a Southern Foodways Alliance symposium. He was cooking the headliner lunch. I was making some snacks prior to the catfish fry. He glided into the kitchen in his ironed whites, donned his spotless linen apron tied with what looked like suede strings, and went about unfolding the most understated, elegant knife roll I had ever seen, all agleam on the inside with Japanese steel. In contrast, I was wearing yoga pants, a T-shirt, and dirty clogs, and had only one knife, wrapped in a dish towel. That day wasn’t the last I had to borrow an apron, but I never attended another event without a knife roll packed full of knives I didn’t intend to use.

Most kitchen professionals dream of the day when line cooks, servers, and managers start referring to them as “Chef.” They can’t get enough of the sound of “Yes, Chef,” “No, Chef,” and “Thank you, Chef,” a litany of reminders of the position they have earned. But even after three years of running my own kitchen, I didn’t let anyone call me such. That only changed when I hired a sous from Colorado and he required that everyone call him chef. He later called me a charlatan to my face as I fired him.

Probably the real root of my insecurities on the chef front lies in the fact that I never set out to be one. I started working in restaurants for the same reason a lot of people do: I needed to support myself while striving for what I really wanted professionally. My goal was to be a journalist, and I certainly didn’t think I could pay the bills doing that. Frankly, I hadn’t even really tried—so I fell back on my college experience and started waiting tables.

I had enough of the performer in me to be good at it, like so many other actors, musicians, and artists who earn their rent in dining rooms from New York to Los Angeles every night. I was the best on the team, actually. (I am confident saying this because when Maya Angelou, Chelsea Clinton, and Monica Lewinsky came in to dine—separately, of course—the owner put them in my section.) Nevertheless, as I do in most situations that suit me, I meandered to something new: the kitchen.

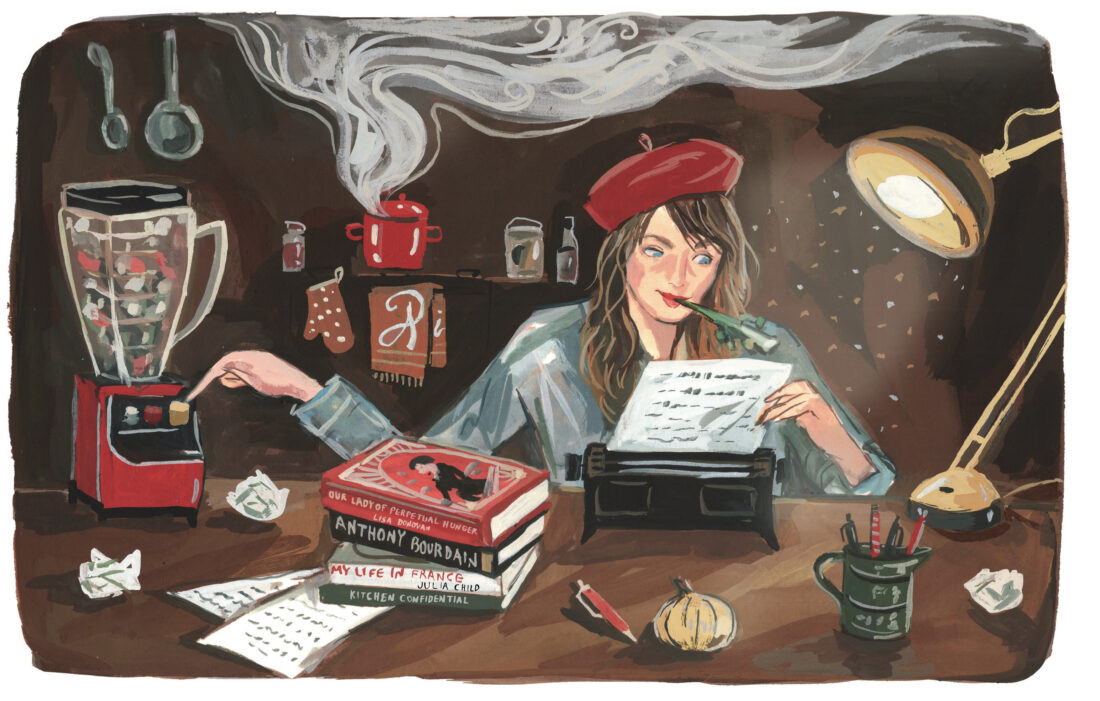

Julie & Julia, Kitchen Confidential, and the weekly New York Times Food section shoulder a lot of the blame for this uncharacteristic, voluntary move to the background. My obsession with food media made me believe that experience behind those swinging doors might inspire me to write something. Ten years later, I suppose, it did. Either way, the kitchen is where I stayed.

I’m not the only one. Gabrielle Hamilton, Amy Thielen, Lisa Donovan, John Currence, and Anthony Bourdain were all chefs before becoming known for their prose. Some of them, like me, studied English or writing in college but found themselves cooking on the line in restaurants because their deep dives in lit and linguistics left them with few résumé-ready attributes. We found a home in front of cutting boards and behind stoves, going in every day to painstakingly sculpt something raw, like a bunch of collards, into something refined, like creamed green ravioli bathed in a warm brown butter with pickled stem vinaigrette, only to send it out into the dining room to be gobbled up by hungry people who would move on to the next dish in a tiny fraction of the time it took our hands to craft it. That process is a lot like whittling an idea into a story and sending that story out into the world for people to experience it in their own way without your oversight.

It’s as painful as it sounds. Maybe I should start painting?