I have long boasted of my ability to keep my head on straight under pressure. Exposed to the dining room by an aggressively open kitchen, I ran a busy restaurant and, on most nights, worked stoically without tantrums or tears, as cool as a cucumber pushed up against a wood-fired oven. When I fried catfish at the James Beard House and watched my rice-crusted fillets sink to the bottom of a cold fryer, I grabbed sauté pans and shallow-fried eighty orders, all under the gaze of A Chef’s Life’s cameras. I am the baby of four sisters, born to read the room and quickly figure out how to stay in it. And…I’m the mother of twins. I don’t panic under stress; I move through it with confidence. Mostly.

It’s taken me till now to identify the brand of kryptonite that renders me a crazy person, but it’s been pointed out to me on too many occasions to ignore: I completely unravel at the thought of not making it to vacation on time. You may be thinking, We all get stressed out at the thought of missing even an hour of vacay. That’s not unique. What’s more, getting to vacation on time is not very important. So shallow! The shallow part I understand. The other part, the part about how everybody reacts the same to the thought of their plane leaving the gate without them, or of train doors slamming inches before their eyes? I disagree.

Last winter, when my daughter and I were running a tad bit late to catch a flight to New York City, I made the snap decision to pull our heavy coats, scarves, and toboggans from our luggage, wearing them instead so we could ditch a suitcase and save time by not checking bags. As I ran, dragging Flo from the parking deck to the terminal, I ticked through the toiletries in my now carry-on and grimaced when I remembered the six-ounce bottle of Augustinus Bader skin cream the TSA agents would relish tossing in the trash.

Inside, perspiring at the tail of a foreboding security line, I tried to pull up our boarding passes on my phone. Problem was, I could only see mine. Flo’s no longer appeared in the stupid virtual Apple Wallet that never has what I need in it, ever. As we crept along the line, I frantically combed through all the other apps one might in order to find the literal ticket to our vacation. No luck.

At ten people or so from the mouth of the line, shouting distance I guess, I held up my phone, now wet with sweat in my trembling hand, and cried for help. “I can’t find my daughter’s boarding pass! I downloaded it to my Apple Wallet, but it’s not there!” A harried TSA agent looked my way, so I lurched to step out of line and fell indiscreetly in a tangle of bags and outerwear on Raleigh-Durham International’s carpeted floor. Had I not publicly fallen, I don’t think I would have started crying. We didn’t make our flight, but we didn’t get escorted out of the airport either, a bonus ten-year-old Flo made sure to highlight.

In my twenties, when I did something like push people aside with both hands to access the opening doors of a train in Europe, I blamed the berserk behavior on my lack of travel experience. We didn’t vacation much growing up, and if we did take a trip, we drove. Although rare, our road trips to Gatlinburg, Tennessee; the Tweetsie Railroad in North Carolina; and my aunt’s house in Seminole, Florida, moved with unneeded urgency. My dad took the wheel, obviously, and above all refused to stop. For him, vacation was more about making good time than having one. To this day the extended Howard family has traveled to only one place together that required an airplane. Several planes, actually, because when twelve of us made our way to Yellowstone for what we knew would be the first and last family foray of its kind, we booked flights on five different aircraft. God forbid one 747 should go down with the full spectrum of Howard genetics on board.

Now that I’m in my forties, I’ve traveled more than enough to make up for any handicap staying put as a young person caused me. Yet, my destination tunnel vision persists in accelerating and narrowing. Just before the pandemic started, I bought a third of a house on Bald Head Island, a seven-mile stretch of maritime forest, beach, and creeks just off of Southport, North Carolina. What I love about Bald Head is how far away it feels. What ignites my stress about Bald Head is that getting there requires a ride on a passenger ferry. Even almost three years into sometimes sporadically, sometimes frequently spending time on the island, the ability to navigate the ferry without acting in confounding ways continues to elude me.

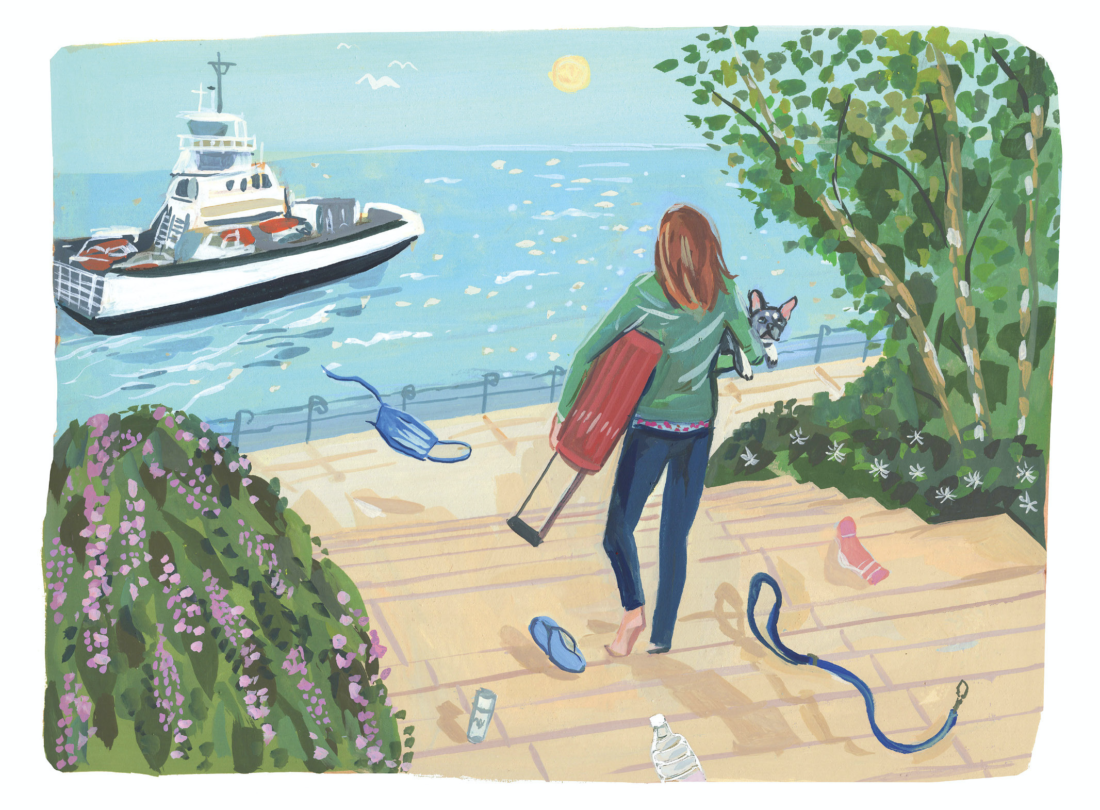

There are real (and, granted, often self-created) pressures. I always seem to have less than a ten-minute window to drop bags, park, buy tickets, and get in line to board. Or there is my previously realized fear of being number one-hundred-and-something in line and getting left on shore for exceeding the passenger limit. On my most recent attempt to chill and relax over there, I was especially pushed for time and pulled into the ferry complex at 1:55 p.m. The ferry left at 2:00, and so my only option was to forgo checking any bags and park straightaway. I would just grab my carry-on. I asked my colleagues coming over later to swing by my car and pick up my computer, a bag of shoes, a cooler of food, and a case of wine. (It was, after all, my birthday week.) They would also have to get the leash for my dog, Tina, because halfway into my sprint across the forever-long parking lot, I realized I’d left it behind.

Pausing to consider for a moment whether to go back and retrieve it, I saw a black disposable mask with a broken strap on the pavement and remembered I still needed one to board the ferry. For cosmic reasons I can’t explain, I ignored all the neon blinking warning signs, picked up the mask, put it on while trying to double loop the broken strap around my right ear, and scrambled to descend the forty or so stairs between me and the ferry line.

With thirteen-pound Tina tucked under my left arm, and a thirty-pound rolling carry-on in my right, doom was inevitable. About halfway down, my new platform sandals slipped out from under me, and I very discreetly slid four steps. I never dropped Tina. My carry-on did not hit the ground, and I did not make a sound. Unscathed and grateful only a few people witnessed the incident, I rushed on the ferry and headed upstairs to hunker on the floor next to the trash can. Right behind me came a fresh-faced, curly-haired twentysomething ferry cop who wanted to know why my dog wasn’t on a leash. Never one to beat around the bush, I pulled away my half mask and skipped the back-and-forth begging him not to kick us off the boat. I said I knew I had made a bad decision and promised never to do it again. If only my neuroses would swear to it, too.