This summer I had planned to interview the Southern authors Beth Macy and Silas House in Hindman, Kentucky, at the Appalachian Writers’ Workshop, now in its forty-fifth year, where I was teaching. Macy was slated to give the keynote, and House, who has taught at the workshop for many years, would be coming down to introduce her. But our plans were suddenly derailed—first by COVID, then by the deadly catastrophic flash floods that ripped through eastern Kentucky in late July.

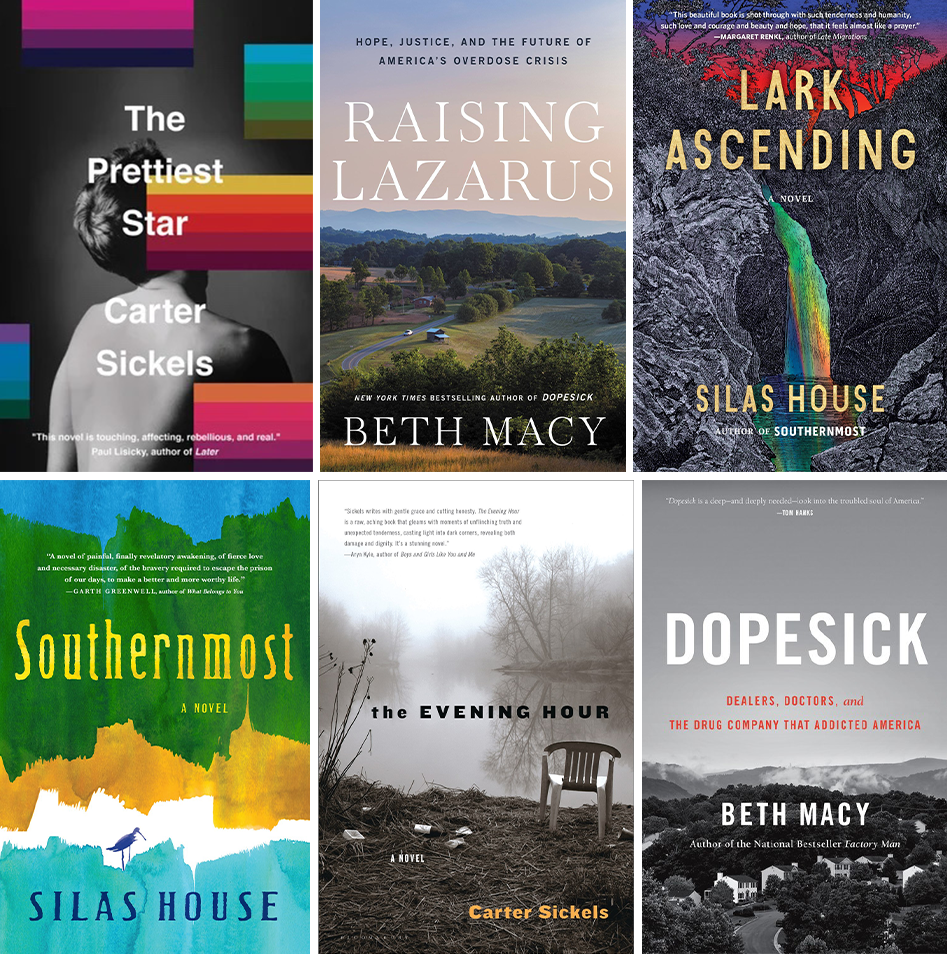

I first connected with Silas House in 2012, when I was still living in Portland, Oregon, after he championed my debut novel, The Evening Hour, about the opioid epidemic in Appalachia and the destructive practice of mountaintop removal coal mining. After I moved to Kentucky for a teaching position in 2016, House and I became friends, and he welcomed me into the writing community—a huge help as I worked on my recent novel, The Prettiest Star, about the AIDS epidemic. It tells the story of a young queer man returning to his home in Appalachia in the mid-1980s. House is the author of six novels, including the award-winning Southernmost, and his new novel, Lark Ascending, comes out at the end of September. Lark Ascending is set in the not-too-distant future, when queer relationships have been outlawed and climate change has scorched the land. The novel follows the protagonist Lark’s urgent journey from the Appalachian Mountains to Ireland, and tells a tale of resistance, survival, and love.

When Beth Macy’s Dopesick was published, I read it in a few days, deeply impressed by her humane reporting on the opioid crisis. Beth was a Roanoke Times reporter for twenty-five years, and she was recently the executive producer and cowriter for the 2021 Hulu adaptation of Dopesick. Her most recent book, Raising Lazarus: Hope, Justice, and the Future of America’s Overdose Crisis, continues to explore the opioid and overdose epidemic. When I learned both Macy and House had books coming out within a few weeks of each other, I wanted to hear what they had to say about what all three of us strive to do in our writing: to tell complicated stories about a region that is susceptible to stereotypes and derision, and to emphasize voices that too often are ignored or silenced, including rural queer people, those struggling with addiction, and the poor and working class.

Though Macy and House write very different kinds of books—Macy writes deeply reported nonfiction and Silas is primarily a novelist—they both write about Appalachia and rural America with clear eyes, complexity, and deep empathy. They’re both successful and productive writers, but they assured me that they don’t always find writing to be easy. “I don’t think you’re a good writer unless you think you can’t do it at the beginning—that’s part of the process,” Macy told me, and House agreed: “I never trust a writer who doesn’t doubt themselves.” In our Zoom conversation—which made me hope that one day I’ll get to spend an afternoon on a porch with them—we discussed what it means to write about Appalachia and rural America. The two authors began our conversation by introducing their new books and what inspired them:

Silas House: Lark Ascending is a book born of grief. I started it shortly after I lost my aunt, who was a real mother figure to me, and I was just trying to work my way through that grief. I’ve always written my way out of trouble. I wanted to write about a character who was experiencing deep grief and trying to figure his way out of that. In the book, Lark manages to hold on to hope, mostly by latching on to things of beauty and wonder. The more I wrote it, the more it became about a collective grief that I think many of us have experienced over the last few years. It all focuses on this one young man who creates a family for himself out of this dog and this woman that he meets, and they’re on an epic journey together.

Beth Macy: When I finished Dopesick, I never want to write about the opioid crisis again because it felt so despondent, especially our nation’s response to it, and I was personally grieving the loss of the young woman whose story I’ve been following for two years who was brutally murdered. But then I started hearing good things [about activists and harm-reductionists in Appalachia]. I always do better when I’m writing about people I really admire. I get a tingling on the back of my neck when a story really moves me, and I started feeling moved by these individuals who were overcoming bureaucratic and legal barriers to offer care to the least among us. Every one of the people I profile in Raising Lazarus truly astonishes me, and I wanted to celebrate them, shine a light on them. They are total badasses.

Appalachia has such a long history of being stereotyped and overlooked by the media. What do you want people to know about Appalachia that they may not see in Hollywood or the news?

SH: Appalachia is not a monolith. Just as there are people who live their whole lives in a holler in Appalachia, there are also world travelers who live in Appalachia. We’re global people, we are people who are totally aware of the world, and we’re modern people. The thing I’m always trying to do in my writing is show Appalachian people as complex and complicated. I never want to romanticize, and I never want to vilify. I just want to tell the truth and present human beings.

BM: In Raising Lazarus, I write about a variety of people. Tim Nolan is a nurse practitioner delivering cutting-edge medical care next to a dumpster at McDonald’s. He does it from the perspective of what he calls liberation theology, and it’s a very spiritual thing for him. Then there is Lill Prosperino, the nonbinary activist and harm reductionist from West Virginia who, true to their Appalachian roots, is making this homemade tincture, this drawing-out salve [intended for abscesses caused by needle use] composed of herbs that they’ve collected from the mountains. I just love that Appalachian resourcefulness, and I think it deserves to be celebrated. I love to surprise people with the ingenuity and the badassery of the people I write about. And one of the things that most made me proud of the show Dopesick was the fact that we didn’t stereotype Appalachia.

SH: I was so moved by the representation in Dopesick. There are so many stereotypes about why people become addicts and it’s usually pretty judgmental, and you tie all that up with the judgments around Appalachia—that show could have so easily been a recipe for disaster. But instead Dopesick makes the characters into such genuine authentic, endearing characters; they’re just real people, and that’s what I love the most about it. I have been told by several people that Beth really pushed them to make sure you know that it was not stereotypical. I’m so thankful.

BM: Thank you, that means everything.

You both write about urgent issues facing Appalachia and rural America. How do you grapple with politics in your work?

BM: In Raising Lazarus, it was the politics that were singularly just so terribly responsible for the lack of evidence-based care reaching the most needy people. It’s not that we don’t know the solutions. We know the solutions; we totally have the ability to implement the solutions, but it’s the politics, the NIMBYism [Not in My Backyard-ism], and the lack of leadership that is preventing this kind of care.

[Macy shares specific stories of how the individuals in her new book, Raising Lazarus, are creating solutions, including a group that provides clean needles and Naloxone, a drug that reverses overdoses.] I start the book with Michelle Mathis, who founded the Olive Branch Ministry, the nation’s first biracial, queer, faith-based harm reduction group. She started it out of the back of her pickup truck, illegally giving out needles and posing as a food pantry. That’s Appalachian resourcefulness! Michelle also told this story about how she couldn’t get the church ladies to help her pass out needles, but she could get the knitting circle to crochet little bags that can hold the needles, and then a month later, she got them to add fluorescent thread so that drug users can see them in trap houses in low lighting areas. She’s made incredible changes [toward fighting the opioid crisis and how we treat people with addiction], and she’s doing this from rural America.

SH: Like Beth is saying, I think we latch on to the human story. I wouldn’t want to read three hundred pages of statistics about drug use. I wouldn’t gain real knowledge from that because it would just bore me to death, but I do want to read about real human beings who are doing that work like Beth shows in her books. And, with my books, I don’t want to just beat people over the head with the issue. I want to show them characters who are dealing with those issues and reacting to those issues. How does this character react to the fact that queerness has now been outlawed in Lark Ascending? Allowing the readers to get to know Lark and Arlo, and care for them, hopefully makes them care about this issue, the criminalization of LGBTQ people, which is not that far-fetched. It’s less far-fetched now than it was when I wrote the book. It’s all about the human story. You have to create characters—or in Beth’s case show us the characters who are in existence—and allow the readers to see them as human beings.

Flannery O’Connor said that people without hope don’t write novels, which I’ll expand to include nonfiction. What do you think?

BM: When I was starting Dopesick, I had a new editor, Vanessa Mobley, who ended up editing Raising Lazarus too. She has this way of looking at my work through a really satellite view that I find hard to do—I find it hard to get so embedded with somebody and focus on all the details, and then still be able to see the big picture. That’s why we’re a good team, because she sees the big picture. She said, ‘Your job is to impose hope and order on a sad and chaotic story.’ For me that was a super helpful sentence to put on a Post-it Note to stick on my computer. It has been my little touchstone saying.

SH: I’m usually writing out of a pretty dark scenario, and I want to thread it through with life and hope. Also, I worked eight years on my novel Southernmost. How do you spend eight years on a book without hope? You have to have hope, to be aiming towards something, or you’ll never finish it. The hope is the fuel that keeps you going, but also the hope that the book can do something positive in the world. When I’m writing, spending those eight years or however long on a book, I just have that hope that I will reach at least one person. That makes it worth it.