The first time Luther Dickinson stepped onto the aged plank floor of the Ocean Springs Community Center in coastal Mississippi, he knew. As he walked amid the mural-covered walls, a maelstrom of colors towering twelve feet from floor to ceiling in all directions, the renowned artist Walter Anderson’s seventy-year-old masterpiece, Seven Climates of Ocean Springs, came alive to the rhythm of his own footsteps.

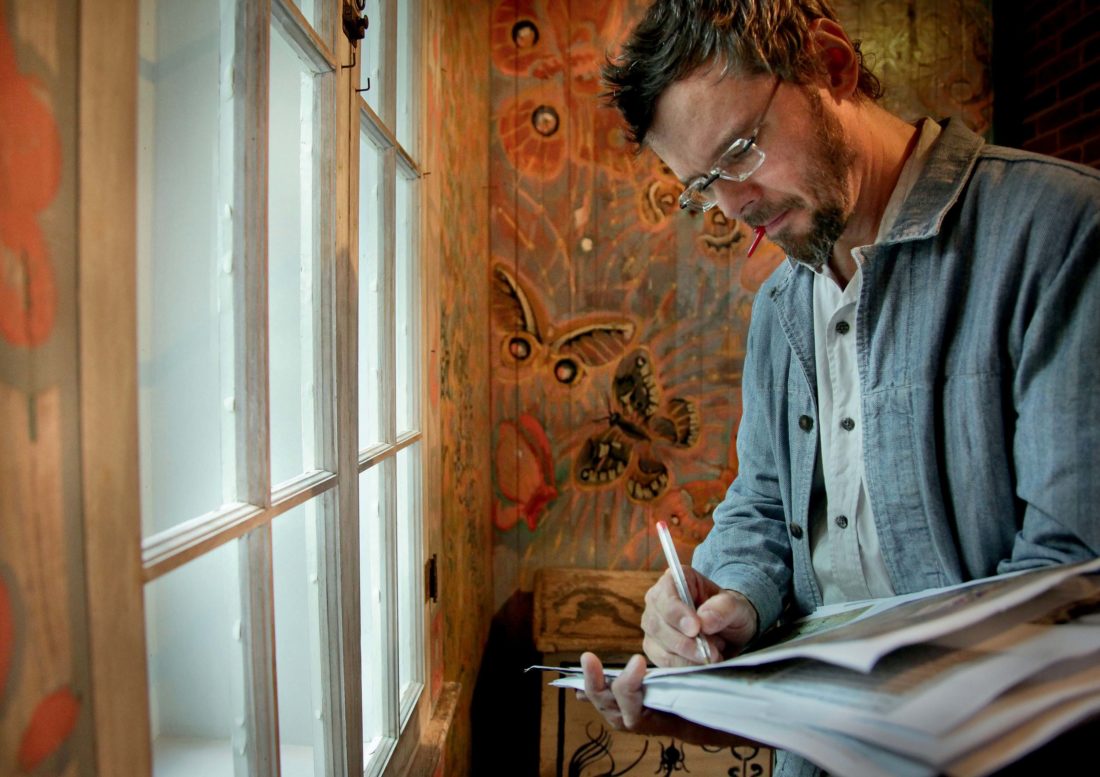

Known for his work leading Hill Country blues preservationists the North Mississippi Allstars and his lead-guitar tenure with the Black Crowes, Dickinson heard Anderson’s trees as strong major chords. Diminished and augmented variations sprouted as hardy limbs. Melodies twinkled on fluttering leaves and rose into the spiral motifs that repeat again and again on the walls. “It was the first time I looked at art and heard music,” he whispers as he takes in the murals again, a few hours before he and a group of fellow musicians give a performance inspired by these works. Retracing his steps, Dickinson snaps his fingers in rhythm, pointing out the nuances of Anderson’s creation. “I looked at the art and saw the stage and said, ‘Oh my God, I’ve got to play music here.’”

Since 2016, Dickinson has done just that, performing at the center annually except for a pause in 2020. On May 15, he will resume the series outside the Walter Anderson Museum of Art in Ocean Springs (which will also celebrate its thirtieth anniversary that day), using digital projection to re-create the murals in an immersive, open-air experience.

From the outside, the community center looks nondescript compared with the vibrant artwork inside. The starch-white brick building faces Washington Avenue, which spans the downtown to the placid shore of Biloxi Bay. The legacy of Walter Inglis Anderson, an art-school-trained painter with a reputation for eccentricity, rests largely right here.

Anderson’s family moved from New Orleans to Ocean Springs when he was fifteen and established Shearwater Pottery on land adjacent to the town’s harbor. Bob, as his family and friends called him, was an adventurer. He had just returned from a sojourn abroad, in fact, as the town was completing construction of the community center in 1950. With the support of the architect and a few local leaders, he drew up an agreement to decorate the new center’s walls with murals for a token payment of one dollar.

“He saw that as an opportunity to give the community an identity, and to some extent, to shape the identity,” says his son, John Anderson, sitting in his late father’s cottage at Shearwater. “Amazingly, the community has taken on the identity he painted.” In the years since Anderson’s death in 1965, Ocean Springs has transformed from a sleepy coastal hamlet to an arts and entertainment destination, thanks in large part to his legacy. The 1991 opening of the Walter Anderson Museum, which a short corridor connects to the community center, accelerated the town’s embrace of Anderson as its artistic soul.

His Seven Climates of Ocean Springs captures the natural identity of the region in an exposition of harmony between nature and art, linking celestial bodies to the seasons. Venus, a focal point, is an illustration of duality in which two eagles interlock at the center of a radiant swirl of energy that draws in fish and birds from sea and sky. “At one point he summarized everything he was doing throughout his artistic career in one sentence,” John Anderson says: “‘In order to realize the beauty of man, we must realize his relation to nature.’ That wall in the community center is an attempt to depict the realization of our relation to nature.”

Not all of the townspeople appreciated his vision. His reputation as the kind of artist who would ride his bicycle to Key West, or feed café au lait to a cockroach from a spoon, didn’t always endear him to other locals. He would often row his one-man skiff to uninhabited Horn Island and camp for weeks to paint the flora and fauna. There were whispers in the community about his mental health, and some even wanted to take buckets of paint and whitewash his esoteric murals. The tide began to turn when the Memphis Brooks Museum of Art hosted a retrospective of Anderson’s work in the late 1960s, just a few years after his death. John, then a student at the University of Mississippi, was amazed by the line of people waiting to see his father’s work. Among them was a young Mary Lindsay Dickinson, Luther’s mother.

Luther reaches into a canvas tote and pulls out a folio of handwritten chord charts and a photocopied booklet full of musical formulas relating to Anderson’s murals. Dickinson first came to the Anderson Museum with his mother after his father’s passing in 2009, essentially to check off one of her bucket-list items. But he left with one of his own. The community center’s murals consumed his imagination and continued to swirl in his head. “It just blew my mind,” he says. “All those crazy scribbles and diagrams—I can’t even go back and retrace that thought process, but it got me here. The scribbles are just the artifact of the process.”

Dickinson conceived a way to traverse all of Anderson’s climates with largely improvisational music. In his imagined animation, the trees unfold as the chords, the leaves and birds become chirping fifes and piccolos, and the larger animals dictate the rhythms. “If you study the way Anderson thought about art, he saw music and art and nature and love all as one thing,” Dickinson says. “I can hear these chord tones and extensions like jazz chords. This bird’s going, booo-be-doo. This cat’s got a vibe—chicka-bon, chicka-bon.”

On the day of his most recent performance here, he spends most of the afternoon setting up his guitars, tuning and checking sound levels for tonight’s mix. New Orleans jazz drummer Johnny Vidacovich, who has accompanied giants including Professor Longhair, plays airy fills around Dickinson as Vaylor Trucks, son of Allman Brothers Band drummer Butch Trucks, uncases his six- and twelve-string guitars. As the audience takes seats around them, Dickinson marks up last-minute changes on the chord charts for Trucks and bassist Dominic John Davis, on break from his gig backing Jack White. The evening begins in the fading twilight, what Anderson called the “magic hour,” inside a curve of candles. Vidacovich shuffles lightly, leading Dickinson’s flamenco-inspired guitar lines. Leif Anderson, Walter’s daughter, begins performing a dance as Trucks and Davis join in.

“Blues for Trees” segues into an interstellar passage, riding a gentle gait while Dickinson coaxes otherworldly chirps from his slide guitar. On “The Inherent 69,” Vidacovich keeps his eyes closed as the band floats through an improvised melody. Then, with a roll on his high hat, they fall into a tight groove. Davis smiles.

Anderson wasn’t sentimental about much of his work. The need to realize nature through art drove his compulsion to create, and once he achieved that moment, the art had served its purpose. Destruction, he knew, is as much a part of nature as creation. The gradually shifting sands of the Gulf of Mexico nudging Horn Island westward, or the hurricanes that gnaw away at its shoreline, wipe the canvas clean so a new masterpiece can begin. Dickinson understands this, too. Each year, his Seven Climates performance reinterprets those initial chord charts as if they were a blank canvas. Just as no two brushstrokes are the same, every performance is unique.

“Change—it is magical,” Anderson wrote in his Horn Island logs after watching his private Eden succumb to the surge and whipping winds of Hurricane Betsy. Like the music played tonight, what is created eventually drifts away. But the magic of the moment lives on.

Jim Beaugez writes about music and culture from his native Mississippi. He has contributed to Garden & Gun since 2021 and has also written for the New York Times, Rolling Stone, Smithsonian, Oxford American, and Outside.