Arts & Culture

A Legendary Bladesmith and the Story Behind His Knives

Jerry Fisk has made just about every type of knife imaginable. Now, along with passing down the skills that have made him a living legend, he’s determined to uncover the true story behind the South’s most famous blade

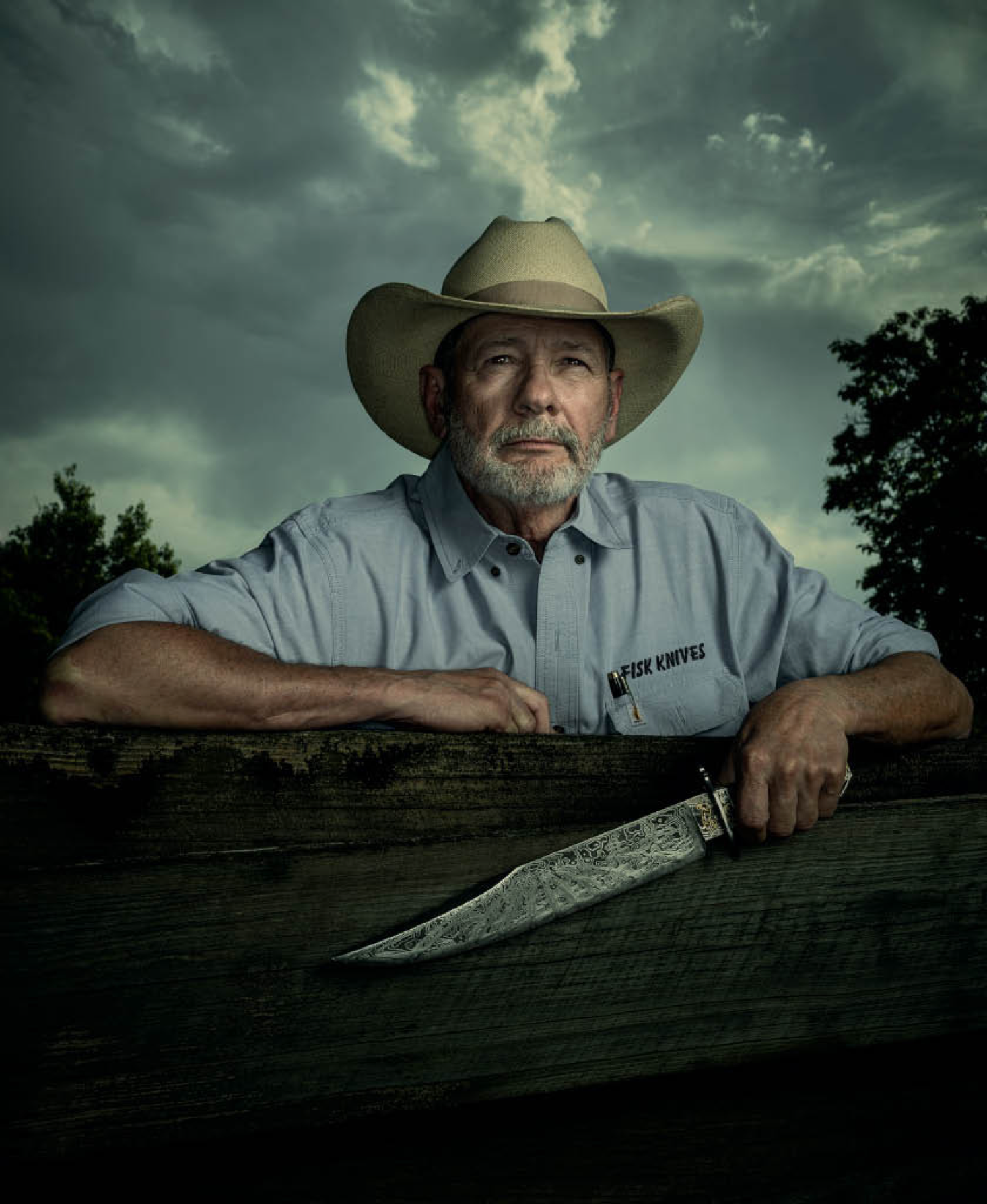

Photo: Dan Winters

Jerry Fisk with a bowie knife on the grounds of the James Black School of Bladesmithing and Historic Trades.

Jerry Fisk never knows where his custom-made knives might wind up, or what task they’ll be called to perform. One client paid thirteen thousand dollars for a Fisk bowie knife, and when Fisk later asked the man what he did with the knife—an ivory-handled Damascus blade with a touch of engraving—the fellow told him, “We cut crust off the toast for the kids.”

Fisk tells me this story while a gas forge is heating up in his Southwest Arkansas shop, and he’s changing headgear from a clean and pristine white beaver cowboy hat to the slightly battered and irregularly singed straw cowboy hat he wears while pounding on glowing hot metal.

“Really?” Fisk replied at the time, incredulous.

“Yeah, man,” the fellow said. “They really don’t like crust. And I want my kids to know that quality matters, no matter what you’re doing.”

Some of Fisk’s knives end up in collections, such as Arkansas #1, a commemorative knife now on exhibit at the University of Arkansas Hope-Texarkana. The ornate blade was commissioned in 2019 to celebrate the heritage of the bowie knife, the most famous knife style in America. Many historians agree that James Bowie, a Louisiana planter and the famed Alamo martyr, had the original bowie knife made in the early 1830s, by a Washington, Arkansas, blacksmith named James Black. The bowie knife and its Arkansas roots are experiencing a renaissance in interest these days, in no small part due to Fisk’s coattails.

Photo: Dan Winters

The tip of a Damascus sword with twenty-four-karat-gold raised flames on the cutting edge.

For Arkansas #1, Fisk forged the Damascus steel blade in his signature Dog Star pattern, with 1,836 layers of metal to honor the year Arkansas gained statehood. The blade contains metal collected from leading Arkansas industries—from a chicken house, a cattle fence, and an old skidder used in the timber business. The handle mountings are fully engraved. Each single leaf, Fisk says, required up to eighty-two chisel cuts.

Other Fisk knives end up in the velvet-lined drawers of collectors, rarely seeing daylight. They are exquisite pieces, boldly engraved, crafted with precious metals and exotic handle materials. They can cost tens of thousands of dollars. Fisk once made thirty-three knives for a single customer: a hunting knife, a bowie, and a folding knife for each of the man’s eleven children and grandchildren. Each knife handle was cut from a single fossilized mammoth tusk Fisk bought for $21,000.

Some customers have exacting requests. One man, who claimed deep Norse roots, asked if Fisk could build a scramasax—a short Viking sword—in the traditional manner.

At the time, Fisk hesitated. He spends plenty of time at the anvil. He pounds on plenty of metal. But a man’s body can take only so much, so he also uses a few modern tools: His workshop holds two gas forges, a power hammer, grinders, and a large hydraulic press.

“I told him, ‘Man, that’s going to cost a lot of money,’” Fisk says. “And he said, right back at me, ‘Son, I have a lot of money.’”

And then there was the father-and-son knife. The one that changed much about how Fisk understood his work.

The father of a young man who was killed in a car wreck in the twelfth grade approached Fisk about making a memorial hunting knife that the family would share. The father and son had a passion for rebuilding cars and trucks and often worked side by side, and the man wanted Fisk to craft a knife from metal taken from the last rebuild they worked on together.

The family sent him the metal glove box of an old truck, and when it was time to forge the blade, Fisk invited the family to the shop. “The dad, the grandpa, the brothers, they all came,” he says, his voice breaking. He drops his head. The group gathered around the forge and the anvil, and Fisk showed the men how to hammer on the hot steel and draw the malleable metal into the rough belly profile of a hunting knife that he would later finish. One by one, they took turns hammering at the anvil.

“Most people,” he continues quietly, “when they first lay their eyes on a knife I’ve made, they’re only seeing five percent of everything I do. They can’t see inside the knife. They can’t see the hours, the weeks, the blood and sweat. They just see the last five percent. But some of them do take it with great consideration. This family did. And I can’t tell you what that means to me.”

“No electricity at all,” Fisk recalls. He grins and shakes his head. “He wanted it hand welded, hand folded, hand everything. He didn’t even want me to use electric lights.”

Photo: Dan Winters

Fisk brings a hot blade to the anvil before pounding it into shape.

Jerry Fisk is a knife maker like Frederick Law Olmsted was a gardener. From his workshop outside the small town of Nashville, Arkansas, not far from the Texas state line, Fisk builds some of the most highly sought knives on the planet. Many are large bowie knives, forged by hand and extensively engraved. They are owned by celebrities and collectors—Fisk does not reveal the names of customers—from around the world. Fisk also builds fighting knives that do not reside in display cases. He’s made knives for members of the U.S. Army Rangers, the Green Berets, the CIA, the French Foreign Legion, and many more. He gets cagey talking about this. “These are serious people doing serious things.”

His work has been honored at scores of knife-making shows, and Fisk has won the American Bladesmith Society’s W.W. Scagel Lifetime Achievement Award and the Arkansas Governor’s Arts Award for Traditional Arts, and he is the first bladesmith to win the William F. Moran Knife of the Year Award twice. In 1999, he was named a National Living Treasure by the University of North Carolina at Wilmington’s Museum of World Cultures, and he has since helped create an Arkansas Living Treasures program through the Arkansas Arts Council that strives to elevate others in the creative fields. Fisk has also served as an international ambassador for the heritage of traditional knife making. His extensive travel and teaching in Brazil helped kick off that country’s meteoric rise in the knife-making world, and he has studied and taught as well in Russia, England, Germany, and France.

Along the way, Fisk has helped to expand the boundaries of what a knife can be. “Jerry is a very important maker,” says Barry Lee Hands, a lauded engraver and president of the Firearms Engravers Guild of America. “He is an innovator, and collectors want to buy stuff from people pushing the boundaries.” Fisk also offers sole authorship of a knife. While many knife makers send their work to engravers for final embellishing, Fisk engraves every tendril and leaf. “There aren’t a lot of makers who do that,” Hands says. “He did not make the mistake of copying his influencers but chewed it all over in his head and came up with something that’s instantly recognizable.”

Fisk’s career tracks a growing interest in custom knife making, which is driven by a confluence of factors. A rising embrace of field-to-table fare has helped push consumers to better appreciate elevated knife design. The History Channel’s wildly popular Forged in Fire television series has certainly played a role. And while the New York Times recently called the high-end knife market “a niche community of knife enthusiasts,” knife design is hardly niche in the hunting and angling and outdoor recreation worlds.

In addition, Fisk lives in the epicenter of American knife design. In 1988, the venerated knife maker Bill Moran and the American Bladesmith Society founded a knife-making school at the Historic Washington State Park, Arkansas’s largest collection of restored nineteenth-century buildings. The school served as a think tank and incubator for modern knife makers for twenty years. There, just a few miles from Fisk’s home, is where many believe James Black hammered out James Bowie’s famously eponymous knife. In 2020, the University of Arkansas took over the school and renamed it the James Black School of Bladesmithing and Historic Trades. It was recently the centerpiece of a weekend celebration that drew more than four thousand visitors. And the crowd was abuzz with headline-worthy news from Fisk: He and a partner recently purchased a twenty-eight-acre tract of land where they believe Black might have had his actual shop. They have uncovered traces of buildings and a possible forge site and are now raising money for professional archaeological studies. The location of the forge that created the original bowie knife has long been a holy grail for knife connoisseurs. Firmly situated on the leading edge of bladesmithing’s future, Fisk now finds himself equally active in its past.

Photo: Dan Winters

Grinding a blade in a shower of sparks.

In his surprisingly tidy shop, at the base of a knoll on a country highway outside of Nashville, Fisk is no sooty Hephaestus, no bulked-up hammer wielder who fits the mold of a brawny blacksmith. At sixty-eight, he is slim and sinewy, with a trim gray beard and an impish demeanor. He loves a good joke and is good at cracking them, often at his own expense. “I missed school the day they taught math,” he might say. Or “I was voted most likely to work at the chicken plant.”

Born in Oregon, he moved with his family to tiny Lockesburg, Arkansas, about twenty miles west of his current home, when he was one year old. There he was one of five boys in a home nearly void of money but filled with love and high expectation. His father made $1.65 an hour working at a local feed store and served as a minister at a local church. The family raised cows and pigs on the side, and the boys were expected to pitch in.

Home was an abandoned railroad depot his father bought for $250. “We were from the other side of the tracks, that’s for sure,” Fisk says with a grin. There wasn’t a huge emphasis on education or the arts. “We had a Bible,” Fisk recalls, “and then we had a book on how to study the Bible. Those were the only books in the house. We didn’t have art classes. I don’t think I ever heard the word art growing up.” He recalls one day sitting down in the living room, drawing, and his father appeared. “If you’ve got time to sit down and draw,” Fisk’s dad said, “then you got time to work. Get going.” When each child turned thirteen, Fisk says, his father “turned us loose. He bought our food and bought us a Christmas present, but that was it.” Clothing, books, transportation—the boys had to work to pay for it all. “He taught us young: Get out there and hustle.”

Even today, despite the accolades and international acclaim, he is reluctant to call himself an artist. “I’m a tool maker,” he insists. “Not an artist. If I have any talent at all, it lies in determination. My dad taught us that who you were came from the limits you placed on yourself. That’s still my approach. If I don’t know how to do something, that just means I don’t know how to do it yet.”

He figured out what he wanted to do when he was ten, during a school field trip to the James Black forge.

“When I walked in, there was a guy playing in a fire,” he says. “He was dirty and making all kinds of noise. Doing everything Mama said not to do. And he was making a big ol’ bowie knife. It was the prettiest, shiniest, sharpest-looking thing I’d ever seen. Oh, my gosh. And that was it. That was the start of all of it.”

Despite the bowie knife’s fame, no one can say exactly what the original looked like. The knife gained its initial notoriety from an epic duel held in 1827 on a Mississippi River sandbar across from Natchez, Mississippi, during which Bowie was grievously wounded yet still killed one of his assailants. News of what came to be known as the Sandbar Fight fueled the frontier public’s infatuation with the knife Bowie wielded. Soldiers, buffalo hunters, senators, and governors strapped the knives to their sides, with foreseeable consequences. Across the young country, according to one breathless account, “Bowies were drinking blood from New Orleans to Dubuque and from Savannah to Brazos.” In 1837, the Arkansas Speaker of the House killed a fellow legislator with a bowie on the floor of the Arkansas House of Representatives. By the mid-1800s, the cutlery industry of Sheffield, England, was flooding American ports with various incarnations of the bowie knife.

After his visit to the forge, Fisk went home, carved a knife from wood, and promptly stabbed one of his brothers with it. “My mom gave me a whooping for that,” he says, laughing, but the die was cast. He was smitten with knives and knife making. Fisk graduated from high school in 1971 and would mark time in a variety of jobs—as a machinist, managing a cement terminal, and as a federal railroad inspector. “And with a little bootlegging on the side,” he says with a wink. In 1972, still struggling to pay the bills, he bought a bar of steel for ten dollars. It was large enough to make two knives, which he sold for eight dollars each. “That was six dollars in profit,” he says, “at a time when six dollars was a pretty big deal to me.”

In 1987, Fisk went full-time into knife making. Two years later, he received his “master smith” designation by the American Bladesmith Society, an incredibly rigorous process that only a handful of knife makers achieve each year. By then he was charging as much as three hundred dollars for a knife, but he was still working in a makeshift shop built out of used shipping pallets. One customer came in from Colorado to pick up a knife and, as he was leaving, told Fisk: “You know, if I didn’t know that my knife came out of here, I wouldn’t let my knife even go into a place that looked like this.”

Photo: Dan Winters

A bowie handle made of wood from the walls of the Alamo.

Today the range of people who find their way to Fisk is mind-boggling. He is currently working on a two-hundredth anniversary commemorative knife for the Texas Rangers. Once, he took a call from Russia and was asked if he could make a shashka, a Russian single-edged sword that dates to the seventeenth century. “Of course, yeah, I can make one of those,” he replied. “And while we’re talking, I’m thumbing through a research book on Russian weapons, trying to see what the hell a shashka is. But I took the job. I didn’t know how to make one, but that allowed me to study. To learn new techniques. To reach further.”

During my visit, we take a break from forging the blade of a new hunting knife design to eat a quick breakfast at Fisk’s house, just up the hill from the shop. Between bites of bread crowned with homemade mulberry jelly and dandelion honey, he takes a phone call: It’s a friend of the family of Teddy Roosevelt on the line, updating him on the family’s efforts to try to get a piece of wood from the back porch of Roosevelt’s “Summer White House,” Sagamore Hill, in New York. He grins. “I know,” he says. “It’s all just crazy.”

In fact, Fisk’s collection of knife-making materials is one reason his work commands such attention. There’s no question that the allure of complex Damascus steel patterns keeps interest high, and Fisk’s skill at forging artistic mosaics is at the peak of the art. But part of what drives the high-end art knife market is an increasingly valuable palette of materials, particularly for handles. Fisk keeps a supply of exotic bone and other natural materials—among them are slabs of mother-of-pearl, stingray skin, antique tortoiseshell, and a walrus baculum, which is the penis bone found in some mammals. A particular passion is tracking down and securing historic woods.

It’s a passion shared by Fisk’s wife, Lorraine. On their first date, Fisk teasingly called her Bob, and the name stuck. She is grandmotherly and bubbly, an integral part of the business and known to an international clientele as Bob. She handles most of the business details for Fisk’s work, and mines news accounts for clues about potential handle sources.

In a separate room off the workshop, Fisk rummages through a storehouse of historic materials while Bob pages through a binder of documents supporting the provenance of each piece. He has a length of rebar and top railing from restoration work on the Statue of Liberty. He pulls out a piece of hull plating that was ripped out of the USS Cole when it was attacked in Yemen in 2000. Wood from the podium at which Ronald Reagan delivered his second presidential inauguration speech. Wood from inside the Alamo; from Robert E. Lee’s birthplace at Stratford Hall in Virginia; from the infamous Andersonville prison, which held Union POWs; from a tree in the yard where Dr. Samuel A. Mudd treated John Wilkes Booth after he shot Lincoln. Bob recently saw that Sotheby’s was going to sell a piece of the wooden post that held the Liberty Bell. Fisk bought it before it could go to auction.

Photo: Dan Winters

Fisk takes a moment to consider the history and the future of the bowie knife.

There’s another room off the main working space of Fisk’s forge. When he opens the door, I see tables strewn with pencil sketches of engraving details, a large painting of a blacksmith at an anvil, and a modern engraving microscope that looks like something from a surgical suite. Light strains of Celtic music spill out; Fisk keeps it on twenty-four hours a day. “This world is different from that world,” he says, nodding toward the main shop. “When I walk in here, I need it to be inviting and relaxing. I don’t even want to see that other world and get distracted by something that didn’t go right at the forge.”

There are a million things that can go wrong while trying to make a knife. Errors in forging, tempering, annealing, grinding. A tiny slip of the engraving chisel. An errant tap of a hammer. According to Fisk, in his first year as a full-time knife maker, he threw out fifty-two knives that weren’t up to snuff—more than he completed. His percentages are better these days, but he’s hardly perfect.

He used to throw not-quite-right knives in the trash, until one day a fellow at a knife show walked up to his booth with a blade Fisk clearly remembered discarding. “He had dug it out of my trash pile!” he says, astonished. Now when a blade doesn’t meet his standards, he buries it. Drives it straight into the ground with a hammer. Jerry Fisk rejects are scattered all over his property—bowies and hunting knives by the dozens. Even a few swords.

Every knife has to work from the word go, he says. “I don’t try to fix a knife that’s not working out. I start over. It can’t be right unless it’s right every step of the way.”

He tells me about an old family friend who had bought a knife in an English pawnshop for ten dollars and carried it off to World War II. “He put it on his side, and on D-Day’s second wave, it was right there with him.” Fisk studied his friend’s knife and determined it was made in the early 1880s. “Whoever made that knife had no idea that sixty years later somebody’s life was truly going to depend on it. I know a number of my knives will stay in a gun safe or hang on a wall. But every knife I make, I have to consider: Is this the knife that somebody’s life will depend on a generation or two down the road? I build every one of them for that circumstance.”

In a neighbor’s pond, he says, grinning, there’s a $7,000 pocketknife with Damascus steel and ivory handle scales. “It wasn’t turning out to suit me,” he says. “I tied it to the end of an arrow and shot it into the water.” Then his smile vanishes. “There’s no middle ground,” he says. “When I make a knife, it’s a yes or a no.”