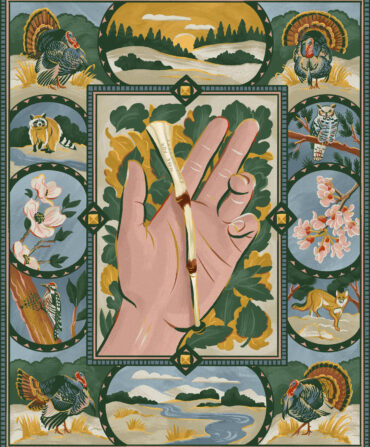

Sporting

A Legendary Carver’s Chesapeake Chops

With a hatchet, a knife, paintbrushes, and a deep reverence for nature and American folk art, Mark McNair turns out some of the finest decoys ever to float the Atlantic coast

Photo: Gately Williams

The Chesapeake Bay glitters at the base of the hill behind Mark McNair as he swings a small hatchet into a block of white cedar, which with each effortless strike looks more and more like a duck.

“I make this look easy because I’ve been doing it a long time,” he says, casually spraying up wood chips like confetti into the sunlight.

It’s a scene seemingly from another time. Dressed in a worn oxford shirt and a frayed straw hat, McNair is at work beneath a craggy juniper tree about a hundred feet from the 205-year-old clapboard house where he lives with his wife, Martha, in remote Craddockville, Virginia, overlooking a body of water that, for centuries, has inspired so many of the nation’s finest carvers of duck decoys. Of that lineage, McNair is perhaps the most celebrated living practitioner.

“He is the dean of contemporary decoy carvers,” says Kory Rogers, the Francie and John Downing Senior Curator of American Art at the Shelburne Museum in Vermont, home to what many consider the nation’s premier public decoy collection. “Albert Davids Laing, Elmer Crowell, Charles ‘Shang’ Wheeler…,” he says, rattling off the names of the legends. “We have all the great masters here, and it really speaks to Mark’s place within this field that he is the only living artist we have in the collection.”

McNair doesn’t seem to know he’s a living legend. He doesn’t even look like he knows he’s at work. He’s just chopping away in his yard, barefoot, making jokes about his so-called job.

Photo: Gately Williams

Handmade knives and chisels and a brant goose head carved from a branch of red cedar.

“It’s work, yeah,” he says as the wood chips fly. “But it’s more like…effort. If it ever turned into that kind of work, I’d stop doing it.”

McNair hasn’t stopped in fifty-one years, though, and now, at age seventy-three, he doesn’t look like he plans to anytime soon. He just keeps chopping away until, after a few moments, he sets down the hatchet and inspects his work, turning the duck in his hands. “It gets slower from here,” he says, and he walks into his workshop.

Decoys are hunters’ tools, objects of deception created by some wily genius who discovered that if he shaped bulrushes into the form of a bird and placed it out on the water, living birds might see the thing from above and be tempted to land, thinking they’d found a good place to eat. The earliest known examples, like the eleven decoys found in a Native American archaeological site in Lovelock Cave in Nevada, are estimated between one thousand and two thousand years old. It wasn’t until the mid-1800s, though, that wooden decoys became commercially widespread in the United States, during a stretch when hunting wildfowl in the Chesapeake Bay was such big business that it is said more ducks were shot there than at any other time or place in America.

All of that ended with the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918, which made the hunting and sale of protected species of migratory waterfowl illegal. In doing so, it also brought about an end to the mass production of decoys. Carving became a cottage industry. “Every waterman, bayman, hunter, or fisherman who enjoyed duck shooting, whether it was one bird for the evening stew pot or one hundred birds for the city markets, made decoys,” wrote decoy historian Henry A. Fleckenstein Jr. of this period, which also marked when connoisseurs first began to recognize decoys as more than just tools, but also as works of fine art.

McNair didn’t know any of this when he was growing up in Guilford, Connecticut. He didn’t hunt, and he didn’t carve birds or own any decoys. But he did know that his father, a carpenter, could make magic out of hand tools and wood. “I remember when the pile of lumber outside turned into our porch,” he says. “And our house too—he built that himself. It was my introduction to wood. It just gives you permission to build things.”

McNair had an early penchant for drawing, and in elementary school, his principal suggested he take art lessons (“She saw me doodling instead of learning my Latin,” he says). He ended up in a class for adults—which included a few Yale professors—all of them working on their oil techniques. “That was a real eye-opener,” McNair says, and by the time he graduated from high school, he’d set those newly opened eyes on becoming an artist. He enrolled in the Rhode Island School of Design, one of the country’s top fine art schools, thinking he might become an architect. Soon, however, he found himself making ends meet however he could.

Photo: Gately Williams

Mark McNair roughs out a shape; his first home workshop.

“I did some antique restoration, and I carved signs,” he says. “I painted houses and played in a band…I was determined to be self-employed.”

This was the early 1970s, when a burgeoning interest in American folk art was influencing the art world. The 1974 landmark Whitney Museum of American Art exhibition The Flowering of American Folk Art, 1776–1876 is one that McNair feels captured the zeitgeist. “That’s exactly what was happening at the time: a flowering of American folk art,” he says. “It all felt brand-new.” Forms that many considered useful only for practical purposes increasingly drew his attention, and one day a decoy resting on a friend’s shelf caught his eye.

“It was a red-breasted merganser,” McNair remembers. “I took it down and looked at it. Not in profile—I looked at it from the top. It looked like an African mask. A light went off and I thought, I’ll make one of these.”

The next day, he made a merganser of his own using little more than a drawknife and an old paintbrush. Soon after, he sold it. The quick turnaround was perhaps a harbinger of things to come: These days, most McNair birds sell before they’re even carved. And while a shorebird of his might go in the low four figures, at auction some McNair decoys have sold at prices more often reserved for luxury cars. In 2009, a rig of five golden plovers went for more than $37,000. (More than a century ago, hunters targeted shorebirds—nowadays shorebird decoys are purely decorative.)

“I don’t even know,” McNair says when I ask how many decoys he carves per year, but his son Ian—who, like his younger brother, Colin, is also a celebrated decoy carver—guesses the number is around fifty. When McNair was younger, he was turning out nearly a hundred a year. Again he demurs when asked how many of those birds sell. It’s Martha who answers for him this time. “All of them,” she says. (Except for the few he keeps for himself.)

Photo: Gately Williams

McNair and a view of Curratuck Creek from his dock in Craddockville, Virginia.

Despite the fawning attention and high-ticket sales, nothing drives McNair so much as the inherent pleasure of craft. It always seems near the top of his mind, as when he steps onto his dock one afternoon and catches sight of a plastic buoy out in the water.

“Those used to be made out of wood,” he says wistfully, watching the buoy bob in the chop. “And some of them were fantastic, even though the people who made them knew they wouldn’t last.” He compares the evolution of buoys to that of decoys, which now also are often made of plastic. He recounts tales of hunters who gladly swapped their timeworn wooden rigs for new plastic ones. “They would just throw the old ones into the woodstove,” he says, sighing. “They just replaced it all with plastic.”

Still, McNair understands. Plastic decoys are light. They’re inexpensive. They don’t wear out, and they work. For him, though, it’s the endeavor of making art by hand that brings the most satisfaction.

“As humans,” he says, “we have the innate desire to make things attractive to us. That’s why I do it.”

Inside his workshop, McNair pulls a spokeshave across the newly roughed-out duck body, curling slivers of wood away from it with such ease that it appears as if he is simply wiping them off. The doors and windows to the small structure are all open, and two flies and a bee dance through the space, moving between countless hand tools and paint cans and art books and birds in progress. Mozart plays quietly from invisible speakers.

“I move around throughout the day,” McNair says, pointing to one workbench that faces east. “I work here in the mornings, because of the light,” he says, and then gestures to the other side of the room, where another bench faces west, “and there in the afternoons, because it’s cool and the light doesn’t cast shadows.”

Photo: Gately Williams

Carving a shorebird with a spokeshave.

He adjusts the duck in a vise, looking for new angles to work. The surface is already smoother and more lifelike. “If you do a good job sculpting it, these lines should all flow together,” he says, illustrating his point by tracing the contours of the bird directly onto the wood with a piece of raw graphite. “See the way this line flows into this one,” he says, following each curve as it leads naturally into another, back and forth, moving all the way to the smallest turn of the beak. “And there,” he says, with one last tiny coil, “the separation of the mandibles…” What’s left is a series of lines so natural they appear to have risen from within the wood itself, as if they had been there the whole time, drawn in some invisible ink, just waiting for McNair’s touch so they could emerge.

Photo: Gately Williams

McNair uses a comb to create vermiculation on a wood duck decoy.

Atlantic white cedar is McNair’s wood of choice, though he enjoys working with unusual materials as well, like a gnarled bend of Southern wax myrtle that he carved into a curved goose neck, or some long cedar roots that he worked into large wading birds. Where he sources his wood, though, can get a bit complicated.

“You gotta know somebody who knows a guy who knows a guy who is maybe willing to share his number,” McNair says, laughing. “And if you call him and he answers, he might show you some trees that he’s got; then maybe, if you’re lucky, he might let you buy a few.”

The right wood is of paramount importance to McNair, and not just for aesthetic reasons. While 99 percent of his decoys will never be hunted over, almost all of them are made to float. He hollows out and weights each one according to tradition, so that if you were to take a McNair decoy out, it would sit on the water the way any honest working decoy should. “I think of them as little boats,” he says.

Photo: Gately Williams

A finished black-bellied plover. McNair originals, including an early wigeon drake, a mourning dove, and swans.

Despite his adherence to tradition, McNair does not practice in historical duplication. He makes his birds using time-tested techniques, yes, but to the eyes of many, he’s really making contemporary art.

“I certainly think Mark is one of the best contemporary decoy carvers in the country, if not the best,” says Burton Moore, manager of art and history exhibitions at Brookgreen Gardens in South Carolina. “And that’s because he has that fine artist’s eye for looking at all the famous pieces of the past and then incorporating all of that into his own design in subtle ways. And he has that Rhode Island School of Design fine art background. He just rolls all of that into a contemporary piece quite amazingly. He’s transcended the decoy.”

It is a sentiment that experts across the field share. “Mark’s work bridges a gap,” says Kory Rogers at Vermont’s Shelburne Museum. “He takes a folk-art-style type of work and makes it something that people who gravitate toward fine art sculpture can appreciate.”

Stephen B. O’Brien Jr., the owner of Copley Fine Art Auctions, one of the leading American sporting art auction companies, adds, “What makes Mark special is his unique ability to not only study past decoy makers, but past artists, whether they are Greek sculptors or Van Gogh or Jackson Pollock.” (McNair’s son Colin works as one of Copley’s decoy specialists.)

McNair is indeed a student of art history, and though he does have a traditional fine arts education, he also spent years on his own gathering whatever information he could about decoy carving, an effort that, before the internet, often required a bit of detective work. Like the day he and a friend found themselves driving a Ford Econoline through a snowstorm in Duxbury, Massachusetts, when it occurred to them that the decoy collector and physician George R. Starr Jr. lived in the area. McNair pulled over at a gas station and looked him up in the phone book. “We called and asked if we could visit, and he said to come right over for supper,” McNair says. After identifying Starr’s house by the decoys lining the windows, McNair says, “we went in and I gave him a shorebird that I’d made, and he gave me advice that has stayed with me forever.”

Photo: Gately Williams

A finished pintail by his son Ian; McNair spends hours at his stool, carving by the window.

So it went for years, with McNair gleaning what knowledge he could and incorporating it into his work. The result is an unmistakable McNair style marked by formal sculptural knowledge and—the trait people perhaps mention most often—a singular painting style that somehow manages to look at once old and new.

“He’s famous with his paint finishes,” Moore says. “Everybody wants to know how Mark finishes a decoy. You know, he uses old Japan oils and secret elixirs…”

“The secret is out,” McNair says, laughing at the idea. “It’s been out for years.” All he does, he explains, is make what he needs by hand. Usually that means combining artists’ oils and Japan Colors, a type of oil paint that dries quickly and flat. The real trick, he says, is in how you apply the paint, and in knowing what you want something to look like. For that, he takes his cues from past masters and from nature itself.

“When you go hunting and you’re watching your birds on the water, or live birds on the water, you’re gathering information,” McNair says. “I get to watch birds in front of my house, and it’s so interesting to watch them come in and go through all of their routines. You see them do different positions that you might not if you’re not exposed to them all the time. Oh, I love that interaction out there. The head position. The attitude of the birds.”

Later, just at sunset, as their boat chops across the ebbing tide in Nandua Creek, McNair and his son Ian spot a few dark shapes moving across the horizon.

“Look at those birds,” Mark says, squinting. “What are those?”

“Egrets?” Ian says.

“Ibis?”

They watch silently.

“No, those are egrets,” Mark says. “They are ibis off the bow, then egrets behind them.”

To the untrained eye, they’re just black dots, moving over the shoreline and soon out of sight. The idea of the birds remains, though, their forms there in the minds of the McNairs, ready to fly back and land.