Arts & Culture

Clay Rice Captures the Lowcountry in Silhouette

Over the past century, the Rice family name has been synonymous with silhouette artwork. Now, with his eyes trained on Lowcountry landscapes, waterways, and people, Clay Rice has made the form all his own.

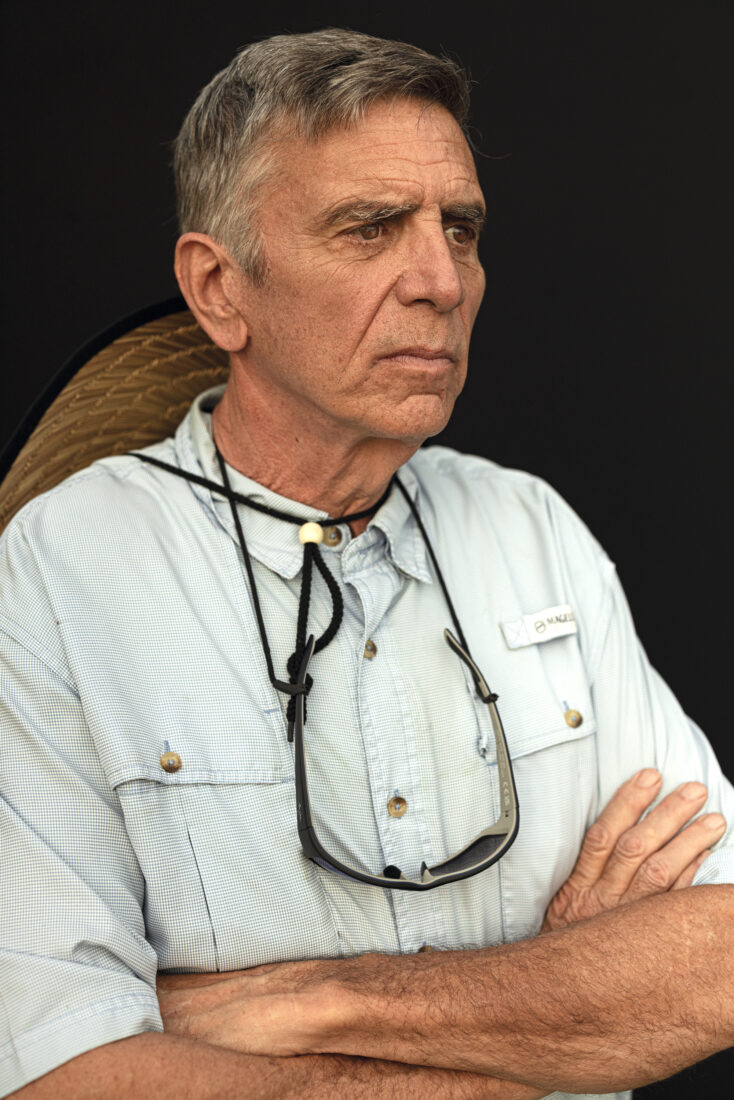

Photo: GATELY WILLIAMS

Clay Rice stands with one of his large metal pieces.

On a road winding through the verdancy of his family property on the banks of the Chehaw River, Clay Rice and I are fifteen miles and what feels like a hundred years from much of anything else. Leaving Brick House, which his great-grandfather bought more than a century ago, en route to a public boat ramp, we see few changes to the landscape other than the sand road giving way to asphalt. Green Pond, South Carolina, seems divinely designed to showcase the best of the Lowcountry, a place effortlessly resplendent, where no one is too important or in too big a hurry to pull off and let you have the road when you’re towing a boat.

Rice stops to let me watch a turkey hen lead her brood into the underbrush. Farther still, a trio of white-tailed deer bound under Spanish moss–bearded live oaks before the paradise unfurling itself transitions to manicured pine savanna. I close my eyes to see cooler days and flagging tails signaling the coming eruption of a covey of quail. It’s a lot of “things you don’t see anymore” all at once, and I’m reminded of Kurt Vonnegut Jr.’s Slaughterhouse-Five, how the character Billy Pilgrim became “unstuck in time,” hopscotching backward and forward along the continuum. I might welcome the condition if it meant regularly landing in this present place.

At the boat ramp, a young man named Lance hails Rice. If Lance cares that he’s talking to America’s most prominent living silhouette artist, he doesn’t show it. We concern ourselves instead with what’s biting, both fish and flying insects—topics so constant in the Lowcountry it’s as if one is in an endless conversation with someone whose face is ever-changing. Lance tells us of his recent luck with redfish and black drum. I hypothesize that the nails of Southerners’ big toes evolved to offer us a means of scratching the backs of our legs when under assault by no-see-ums. But for Rice’s fiberglass boat, there is little about the day that could not have transpired between our grandfathers. In Rice’s case, it almost certainly did. I share the thought with him, and he smiles. “This place hasn’t changed since I was a child,” he says. Rice is well positioned to judge, descended as he is from a family who has been telling the Lowcountry’s stories in art and literature from Brick House for more than 130 years.

For forty-three of Clay Rice’s sixty-six years, he’s used scissors and black contact paper to capture silhouettes, many of them portraits of children, just as his grandfather Carew Rice famously did for more than fifty years before him. Carew’s career is an obvious influence upon him, as is the writing of his great-grandfather James Henry Rice Jr.

Photo: GATELY WILLIAMS

Clay Rice.

As the editor of the Columbia Evening News, James Henry was both ardently pro-development and a passionate naturalist and wildlife conservationist. Perhaps the man who became South Carolina’s first state game warden in 1911 couldn’t have envisioned the hunger with which developers would someday consume the place. But in both his editorials and in two books, James Henry, who was born in rural Upstate South Carolina, wrote excitedly of the beauty and opportunity he found along the water. In Glories of the Carolina Coast, he described the view from Brick House: “No mountaineer ever saw such scenery as one may behold any day and night between the Chee-Ha and the sea, or almost anywhere in these lands of charm.”

Carew, James Henry’s son, grew up at Brick House, beholding that scenery day and night before attending the University of Chattanooga. There, Clay says, “he took an art class and started cutting profiles. He cut a silhouette of a blue jay and a squirrel, realized he had the skill, and his scenes got more and more elaborate.” As a young adult during the Great Depression, “he thought, ‘This is a way to make extra money. If I don’t charge a lot for them, maybe people might buy them.’” The work became a consuming passion that took him across America and Europe. “He was just obsessive,” Clay remembers. “It was the creativity in him coming out. He just had to do it.” As a child, Clay sometimes picked up his grandfather’s scissors, but after a year of college, he struck out for Nashville hoping to work as a songwriter. In 1978, Music City was looking for another Anne Murray or Conway Twitty—now the man who still deeply reveres Guy Clark says, “I’m not even sure Nashville was the place for me, because I was more into Springsteen.” After three years, Clay headed back to South Carolina, where his mother said, “You might want to try something different.”

He began cutting silhouettes “just to see if I could do it,” he says. “I started out with little things I could sell to gift shops. And then I went up to the Hammock Shops in Pawleys Island and cut silhouettes in the summertime.” People lined up for young Clay’s cutouts, many remembering his grandfather. He recalls thinking, “‘Wow, this is good.’ I was good at it, I liked it, I liked meeting the families, and they genuinely liked what I did.”

Photo: GATELY WILLIAMS

Shaping an egret silhouette with custom scissors.

Clay calls silhouettes “a quirky little corner of the art world.” It’s also an ancient one, stretching back to Greeks etching profiles on pots. The iconic black-on-white form emerged in eighteenth-century France before arriving in the British colonies. “The earliest reference to silhouettes in [what is now] America was actually in South Carolina,” says Lea C. Lane, a curator at the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, part of Old Salem Museums & Gardens in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. “There’s a 1769 letter from Harriott Pinckney where she references the artist John Wollaston, writing, ‘Wollaston has summon’d me to-day to put the finishing strokes to my Shadow.’”

Silhouettes were then often made with a machine called a physiognotrace, which allowed artists to quickly outline a person’s profile. The speed of production made custom art available to the masses. “All those things together added to the popularity, both in the North and the South,” Lane says, “especially because you see a lot of itinerant artists traveling from community to community to meet demand. Clay Rice is part of a long continuum of this art form in the American South, which puts him within this national and international context.”

As Clay’s career blossomed, he began driving thousands of miles a year in a camper van, cutting around ten thousand children’s portraits annually. By layering papers, he cuts a stack of three silhouettes (grandparents usually want a copy) every two and a half minutes. After shaping, by his estimate, 1.25 million pieces, his hands are those of a workingman as much as of an artist, rough and gripped by arthritis. Surgery left him unable to make a fist with his left hand, the one with which he holds paper. His right hand feels the pain too, so he modifies his scissors, welding on thumb loops to stabilize them.

The nearly continuous century of silhouettes cut by both him and his grandfather means that someone whose silhouette Carew once cut may now bring their grandchild to have a silhouette cut by Clay. “I just think there’s such an emotional tug about a silhouette,” says Joy Leavitt, a Bostonian who hosted Clay at her children’s shops in Connecticut and Western Massachusetts for more than a decade. “Seeing that baby’s little nose and lips and the little sprouts of hair on the top of their head when they were little, or the long braids and bow—it’s pure Americana.”

For both Carew and Clay, portraiture laid the foundation for something bigger. At Brick House, Clay spent summers watching Carew focus his art on James Henry’s “lands of charm,” cutting scenes of mallards flaring to land, Gullah Geechee people fishing from pirogues, and Charleston’s and Savannah’s ornate iron gates. Some of the images illustrate James Henry’s second book, Aftermath of Glory. Clay, too, has expanded his work, cutting landscapes and wildlife images that over the years have grown larger and more complex than his grandfather’s. Some he cuts from traditional paper; others are massive artworks he renders in wood and steel.

Photo: GATELY WILLIAMS

A portrait Rice cut of the author.

His love of music, too, has evolved in an unforeseen way: He never stopped writing songs, and he wrote and illustrated six award-winning children’s books with as much of a musician’s understanding of pace and rhythm as a storyteller’s sense of plot and purpose. Of the songs Clay sang and the books he read in her Northern stores, Leavitt says, “The kids were just enchanted. He’s like the pied piper. And New Englanders love his beautiful accent.”

Like a creek through the tidal marsh, Clay’s life has twisted back on itself in unexpected ways, turning those little things he could sell to gift shops into a bridge between folk and fine art, a literary and musical legacy, a human connection, and a decades-long love letter to the people, wildlife, and legends of his home.

As we follow the Chehaw’s sinuous turns through the spring marsh, that impossible green streaked with winter’s brown promising an emergence from the dead time, Clay drives his boat the way he cuts a silhouette. Hands moving by muscle memory as much as conscious thought, he navigates the sandbars and mudbanks rising from the shifting tide as surely as the shapes he brings forth from paper. There is a richness here, missed by those who see only pluff mud and marsh grass. But for Clay, part of the fourth generation of Rices to live here, every hummock, island, and creek in the ACE Basin, the massive wetland named for the Ashepoo, Combahee, and Edisto Rivers feeding St. Helena Sound, holds a story he is compelled to tell.

Rounding a river bend, we come upon a pair of crabbers, Arthur Ford and Eric Bernabe, and Clay cuts the engine to speak to them. Crabbing is a hard business, one Ford has been in his whole life, with Bernabe assisting him for almost three decades. They rarely come this far into the ACE, they tell us, but it’s been dry, forcing them deeper to find their catch. It’s a testament to the unassuming intimacy of Lowcountry life that we can hail a pair of strangers, tie up to their boat, inspect their bushel baskets of blue crab, and ask about life on the water. “I’m very drawn to the people who work the water,” Clay says over the whine of the boat engine as we depart. “There’s a lot of art in what they do.” Their work inevitably finds its way into his, but Clay’s own life imbues his work, too, with a kind of know-it-when-you-see-it authenticity of which he says, “I grew up hunting and fishing. By writing or painting or cutting what you know, and what you think is beautiful, someone walks by, and it speaks to them. You put them there even if they haven’t been to that place.”

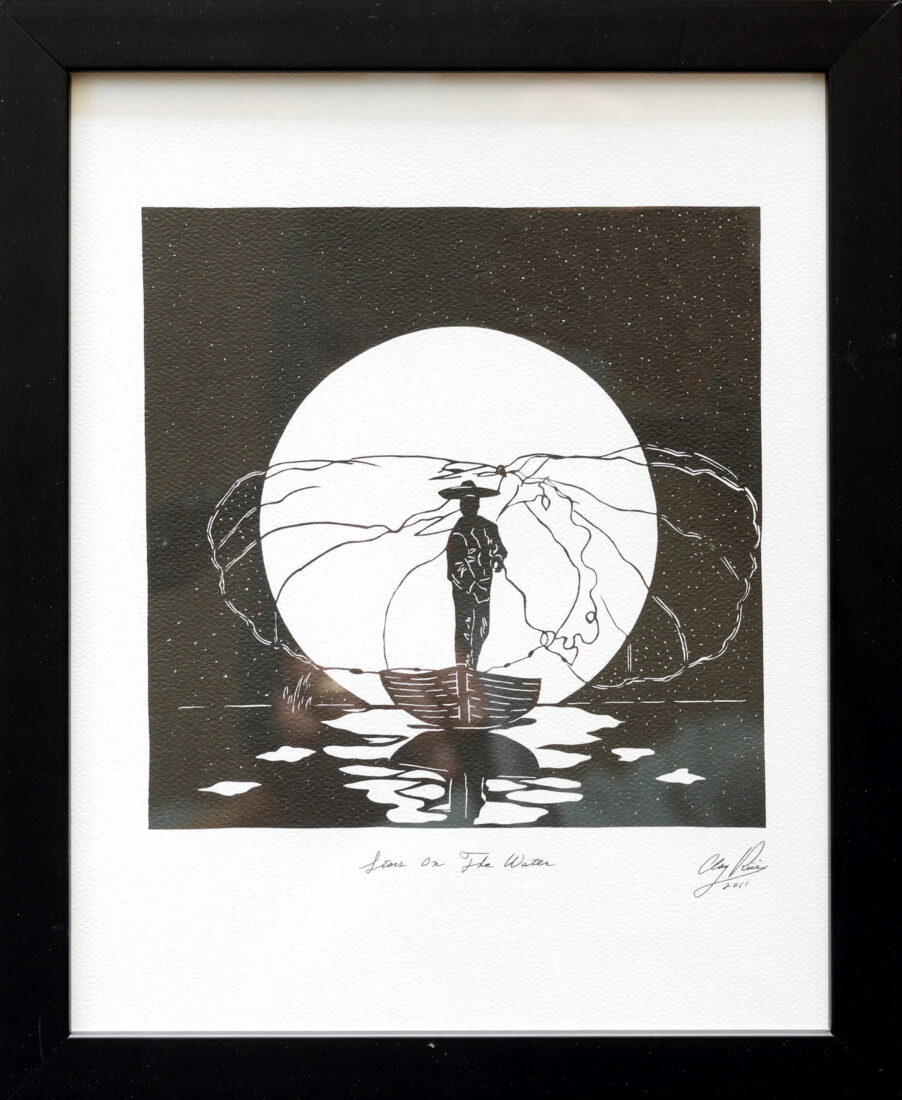

Illustration: Clay Rice

Stars on the Water, a 2011 artwork.

Each of Clay’s pieces incorporates hidden details, much like the place that inspires them. Beyond the central image, which might be a deer or an angler or the Lowcountry legend Dr. Buzzard, there is, for instance, a great blue heron hidden in the corner or a turkey peeking from the palmettos. In a scene cut into polished steel for an anniversary gift, thirty hearts merge to form a cloudscape, representing thirty years of marriage. It is the kind of detail one might miss without paying close attention, like the alligator we saw while heading to a sandbar where Clay cast his net for baitfish. His art is life as he knows and has known it, rendered simultaneously with softness, precision, and the realization that what is present is shaped by what is taken away.

In the years since my own first encounter with Clay—by happenstance in a bookstore on Edisto Island—I’ve met attorneys from the Upstate, writers from the Midlands, and farmers in the Pee Dee whose faces light up upon mention of the Rice legacy. Once, while standing at the edge of a dove field in Hartsville, South Carolina, with my friend David Segars, I mentioned Clay. Minutes later, our shotguns cased, David’s parents, Goz and Pat Segars, were graciously showing me through their home, adorned with Rice silhouettes. Sitting at the kitchen table, which was made from a sheet of glass laid over a Clay Rice torch-cut steel image of an oysterman poling himself and bushel baskets of oysters through the marsh, Goz said, “I grew up knowing Carew Rice. He would come to our house and spend the night, telling stories and talking. He was invariably working under the table with his hands, and at breakfast one morning, he pulled out a silhouette. Another time, I traded him a couple of axe handles for a silhouette.”

Photo: GATELY WILLIAMS

Rice on the Chehaw River at sunrise.

A similar scene played out while I was slurping oysters with new friends during Charleston’s Southeastern Wildlife Exposition. I mentioned Clay, and Brooks Geer, co-owner of Awendaw, South Carolina’s Sewee Outpost store, smiled. “A silhouette from his granddad is one of my earliest memories because there was one on my mom’s dresser,” he said. “Now Clay is continuing the tradition, and I have a chance to be part of it.” Geer sells Clay’s prints and books, and he and his family have spent time at Brick House and fished with Clay, whom Geer calls “the Renaissance man of Lowcountry South Carolina.” Geer motioned over Stratton Lawrence, who’d spent months on the road as Clay’s assistant in 2004 after answering a Craigslist job listing. “It was my first really close view of an entrepreneur doing something for himself,” Lawrence said, “creating the life he wanted, only working for himself to do it.”

Later, Katy Perrin, owner of Port Royal, South Carolina’s Windhorse Gallery, told me: “What you see in his silhouette cuttings comes from just how immersed he is in what we all love about living here and the outdoors. Clay Rice is the Lowcountry.”

Sitting on his front porch at Brick House, rocking and admiring the scenery that has inspired so much of his work, I realize that Clay Rice’s true art is storytelling, documenting the unique beauty and magic of a place that, for all the strength of its culture and traditions, is under constant threat of figurative and literal erosion by forces man-made and natural.

Photo: GATELY WILLIAMS

Rice cuts a silhouette on his family’s land in South Carolina.

Clay stands at the top of his quirky little corner of the art world. But he still defines success as “your next piece being your best piece, and the piece that you just finished, you’re really, really proud of.” The next pieces are in Clay’s head, those wide landscape cuttings mattering more and more as the time he has to produce them is diminished. “At my age, you start thinking about retirement, how much longer you can be out there,” he says. “I like to be at my place in the Lowcountry. I can work at my own pace, cut those larger silhouettes. You can’t just do those in a day.”

Though Clay has two sons, both have their own lives, and even if they were inclined to follow him, he does not want them to have to work as hard, or travel six to eight months a year, as he has. With no heir apparent to a century-old family tradition, each piece might be considered a requiem. But Clay Rice doesn’t concern himself with such matters. He stands on a piece of ground he loves, part of a legacy he’s rightly proud of, all of it sprung from that ground. And for now, the tide is running fast, and Clay knows a spot that will produce redfish. “There’s still room, a lot of room, out there to have art that soothes people if you can give them something that just slows them down a little bit and says, ‘You know, it’s still a beautiful world out there.’”