Arts & Culture

Ernest and Me

As a student, author Wiley Cash discovered the work of the incomparable Louisiana writer Ernest J. Gaines. It was the start of a literary bond that has lasted two decades—and an education in the power of the place you call home

Photo: Ashleigh Coleman

Ernest J. Gaines became my literary hero in 1997, when I was a sophomore creative writing major at the University of North Carolina–Asheville. I had purchased his story collection Bloodline at the bookstore one morning, and by that evening I had given myself over to the book so completely that each of the stories about rural life in Louisiana seemed as real to me as the Blue Ridge Mountains that loomed outside my dorm room window.

Two decades later, when I think about the book, an early passage from the story “The Sky Is Gray” still comes to mind. In the story an African American boy named James and his mother are waiting for a bus that will take them into the segregated town of Bayonne, where the boy will have an aching tooth pulled by a white dentist. Bayonne is a fictionalized version of the town of New Roads, near where Gaines was born on a plantation outside Baton Rouge. The story is the perfect coming-of-age tale, but what struck me in 1997 and what strikes me now is how James speaks of the only place he’s ever known:

It’s a long old road, and far ’s you can see you don’t see nothing but gravel. You got dry weeds on both sides, and you got trees on both sides, and fences on both sides, too. And you got cows in the pastures and they standing close together. And when we was coming out here to catch the bus I seen the smoke coming out of the cows’s noses.

The landscape Gaines evokes in Bloodline—sugarcane fields, crumbling plantation houses, small dusty towns, and the meandering river—not only felt real to me, it somehow felt familiar. I was so taken with the clarity of these images and the precision of the prose that the next day I began writing my own story of rural African American life on a plantation just west of Baton Rouge. If you were to read my story about a young African American man who wields a machete while working sugarcane—and I hope you never do—you would read a story by a young, impressionable writer who had fallen prey to the kind of magic the best writers are able to conjure: Gaines made me believe I could tell a story about a place I had never visited and a people I had never known. What business did I have attempting to portray the African American experience in the plantation South in the years after World War II? After all, I was a white, middle-class kid from an old mill town in North Carolina. The only person I had seen swing a machete was Paul Hogan in Crocodile Dundee. The people in Bloodline were not my people; they were Ernest J. Gaines’s people: African Americans who had been born and raised on plantations in an area known as False River, Louisiana, where their ancestors had been slaves and, later, sharecroppers.

Photo: Ashleigh Coleman

Ernest J. Gaines at his home in False River, Louisiana.

My people were from Western North Carolina and the farms of the South Carolina Upstate, and although they shared the same region we know as the South, their experiences were obviously far different from that of African Americans living in Louisiana in the first half of the twentieth century. Yet, there was a commonality in the imprint land had left upon them. My great-grandparents were poor tenant farmers, and I grew up hearing people tell stories of hope and failure and migration from one patch of dirt to another. My grandparents were of the generation that walked off farms to find work in textile mills, and while both of my parents were born in mill villages, they left them behind for the suburbs as soon as they could afford it.

Each generation that preceded mine moved me farther away from the land that had once dominated my family’s way of life, but I still felt and intuited some kind of connection—what I have heard my friend and fellow writer Ron Rash refer to as “blood memory”—to the landscapes that had anchored my family for generations. When I read Gaines’s fiction, I was able to reclaim some measure of that connection. As a college sophomore, I had not yet read fiction by Lee Smith, Charles Frazier, Thomas Wolfe, or Rash, writers whose regional and cultural experiences so closely resembled my own. But I had read Ernest J. Gaines, and because I did not know how to chase my own history, I chased his instead.

A dirt road through sugarcane fields near Gaines’s home.

In early 2003, my chase led me to apply to graduate school at the University of Louisiana–Lafayette, where Gaines served as the writer in residence and taught an annual fiction workshop with only a handful of coveted seats. He had been offered the post in 1981, when he was living and writing in San Francisco after leaving his home in False River in 1948 at the age of fifteen because segregation rendered further education unavailable to African American children. But he had kept the landscape in his heart and mind, and every word he has written since is an invocation of it.

By 1981, Gaines had published Bloodline (1968), which was preceded by the novels Catherine Carmier (1964) and Of Love and Dust (1967). But it was the story of an elderly woman who had been born into slavery and lived through the civil rights movement that had made him a rising literary star. The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman was published in 1971, and three years later a television movie based on the book won multiple Emmy Awards, including Best Actress for Cicely Tyson. The novel In My Father’s House was released in 1978, followed by A Gathering of Old Men (1983), which also became a television movie. If Gaines’s star had been on the ascent for years, it exploded in 1993 with the publication of his novel A Lesson Before Dying. The story of a condemned man on death row and the schoolteacher tasked with helping the man achieve selfhood won the National Book Critics Circle Award and has sold millions of copies around the world.

Aside from applying to the graduate program in English, I also had to apply for a spot in Gaines’s workshop. I was still living in Asheville in the spring of 2003 when I received word that I had been accepted to both.

By the time I sat down at the table in Gaines’s class that fall, he had been running workshops for more than two decades. Not only that, but he had been a student in one of the most iconic workshops in American literary history. In 1946, the famed author Wallace Stegner began a program at Stanford University that is now known as the Stegner Fellowship. Stegner invited Gaines to join his workshop in 1958. Other writers in Gaines’s cohort included Wendell Berry and Ken Kesey. Future classes would include Larry McMurtry, ZZ Packer, Alice Hoffman, Jeffrey Eugenides, and Tobias Wolff.

Photo: Ashleigh Coleman

The one-room church Gaines restored and moved to his property.

The weight of history and the scope of his literary achievement entered the classroom with Gaines the first time I laid eyes on him. At seventy he looked a little older than the author photos I had seen, but his height and the calm, resonant tenor of his voice made his presence commanding. At our first meeting he let us know that there would be no syllabus for our workshop. The class was based on sharing stories, and in fact, there were only three rules: One, bring a typed one-page response for each story; two, bring your ideas and be ready to discuss them; three, bring cookies if it is your night to bring cookies. Over the next few weeks, the man I had revered as a literary god became a thoughtful teacher who could be by turns funny, serious, and philosophical. There were many nights that semester when I laughed so hard at something Gaines had said that I wiped tears from my eyes, but there were just as many nights when his stories of his early struggles to publish his work left me walking back across campus in the smothering heat, my mind reeling with concerns about my own ability and questions about what I was doing so far from home.

The first story I turned in for workshop—about a guy who gets a tattoo in honor of his deceased brother—was polished and complete, and I wanted both Gaines and my classmates to believe that my work was always as solid as I felt this story to be. The response was generally positive, but I immediately knew that I’d wasted an opportunity to submit a story that needed the intense feedback my classmates and Gaines were willing to give. The second story I submitted—about a wayward alcoholic who has recently moved in with his mother—was a work in progress. Although the story’s narrative was weak—it was told from the point of view of the alcoholic son—I was confident that the writing itself was strong. And then Gaines read the following line aloud to our class: The moon hung in the sky like a foggy red blister against the blackness. I will never forget the look on his face as he stared at the ceiling for a moment. He lowered his gaze to the faces around the table. “Have any of you ever looked up at the moon and thought that?” he asked. He turned to me and said, “No struggling alcoholic who’s moved back in with Mom is going to look at the moon and think that. Write what’s true, not what’s pretty.”

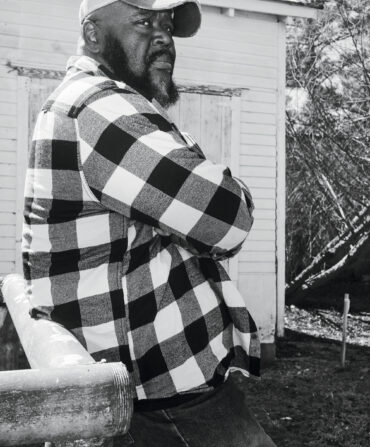

Photo: Ashleigh Coleman

The author in the chapel.

I thought back to “The Sky Is Gray” and James and his mother waiting for the bus on that cold morning outside Bayonne. I remembered the gravel road, the weeds growing along the fence, the smoke steaming from the cows’ noses. I remembered the clarity and precision of the prose and how Gaines had captured exactly what he wanted the reader to see. I wanted my readers to see the moon, so the moon—not some semblance of it—was what I had to show them.

A few months later on all Saints’ Day, Gaines invited our fiction workshop an hour north to False River. He and his wife, Dianne—a New Orleans native and retired attorney who had been living and working in Miami when the couple met—had purchased a plot of land and begun constructing a house next door to the plantation where Gaines was born and raised in the quarters. He and Dianne had taken the white one-room church from the quarters, where he had worshipped and attended school before leaving for California, and restored it and relocated it to the backyard of their new home. They had also purchased the old slave cemetery that sat in the middle of a sugarcane field about half a mile behind the property. As they had every year in the past and as they will every year in the future, descendants of those buried in the cemetery and friends from the area had gathered to beautify it.

That morning, I swung a machete for the first time. I hacked away at vines and encroaching limbs until I felt someone’s eyes on me. I turned to find that a group of older men had paused in their work to watch me. “Where are you from?” one of them asked.

“North Carolina,” I said.

“They don’t use machetes in North Carolina?” another asked.

Later, Gaines and I stood talking in the shade of towering oaks on the edge of the cemetery. On the other side of the trees, sugarcane formed a wall so high that I could not see over it, but in between rows were breaks that offered glimpses of what lay across the field. At the end of one row I could see the still-standing master’s house.

“My grandmother spent her whole life inside the kitchen of that house,” Gaines said. “She never once entered through the front door. None of us did. We always had to go around back.”

Illustration: Ashleigh Coleman

The original house on the plantation where Gaines was born and raised.

Although I could not see it from where we stood, I knew that the Gaineses’ new home sat not too far from the “big” house. I pictured the old church where it rested in their backyard, the late morning sun glinting off its new tin roof.

“What would your grandmother think about you coming back here?” I asked. “About you building a home on this land, about you restoring the church?”

He thought for a moment and looked out over the graveyard where her headstone rested.

“I don’t know what she’d think,” he said. “But it makes me proud.” He turned toward the cane and the house in which his grandmother had worked. “It makes me proud that even if she couldn’t walk through the front door of that house, she could walk through the front door of the house next door, because I own it.”

While we stood there, Gaines pointed out graves and told me brief stories of the people buried there. At one point, he looked at me and then gestured toward a marker. “Do you remember Snookum from A Gathering of Old Men?” he asked. Of course I remembered Snookum, a young boy whose narration opens the novel. “He’s buried right over there.”

Even before visiting False River, I knew this landscape held a holy place in Gaines’s heart, but after that morning in the cemetery, I understood that it also held a holy place in his fiction. I was standing on the land where the century-old Miss Jane Pittman had talked to oak trees, where the hardened schoolteacher from A Lesson Before Dying had decided that even a condemned man is worth saving, and I knew that if I asked him, Gaines could take me to the very spot where James and his mother had waited for the bus, the same spot I had first discovered all those years ago in my dorm room in the mountains of North Carolina. Throughout Gaines’s life, as story ideas came to him, he passed them through the filter of his own experience. To walk the place of his birth is to walk the pages of his fiction, and now he had returned to reclaim it.

Photo: Ashleigh Coleman

Family members rest in a cemetery that Gaines maintains.

That fall, I had been wrestling with an idea for a novel that I did not believe I was capable of writing. Another of my professors had shared an article about a young autistic boy who had been smothered during a healing service at an African American church in Milwaukee. Although the story was tragic, I was interested in writing about a group of believers that would literally believe something to death. But I was hesitant to attempt to tell the story of the boy and his family; I had never visited Milwaukee, and I could not speak to the African American experience there.

On the drive back to Lafayette from the cemetery that day, I thought about the boy who had died inside the church, and, just as Gaines had, I thought of the places I knew, the places I grew up, where a tragedy like this could unfold. As I drove, low-hanging clouds rolled away from me across the flat Louisiana landscape, but when I squinted my eyes, I found that I could make the clouds look like mountains. Later, at my desk, I reimagined the story of the boy’s death and moved it to the mountains of North Carolina. That story eventually became my first novel, A Land More Kind Than Home, and Ernest J. Gaines was the first person whose praise appeared on the book’s jacket. I had become a North Carolina novelist by way of Louisiana.

Although Gaines would retire from teaching in 2004, I grew close to him and Dianne before completing my graduate work in 2008, regularly attending the cemetery cleanups, accompanying them to readings and book signings, and spending time with them when they returned to Lafayette to visit the university or one of their favorite restaurants. There were times when I would forget that I was riding in the car or sharing a meal with one of the country’s greatest living authors, a man who had received the National Humanities Medal from President Bill Clinton and would go on to receive the National Medal of Arts from President Barack Obama. And then something would happen to remind me of who he was and everything he had accomplished. Perhaps he would recount a story about when he and Dianne had hosted Oprah Winfrey, or perhaps I would come across a photo of him with Ralph Ellison or some other iconic writer. Then there was the time I was visiting the Gaineses for lunch and he opened an envelope to find a letter from his old friend Wendell Berry along with a handwritten poem he had dedicated to Gaines. A few weeks later I drove up from Lafayette and found Berry and his wife, Tanya, sitting on the porch with Gaines and Dianne, laughing over stories about their time in Stegner’s workshop—two young men, one from Louisiana, the other from Kentucky, thrown in with writers from California and New York. I listened as Gaines recounted a story about the very night that he and Berry became lifelong friends.

“Stegner always wanted his students to spend time together outside the workshop,” Gaines said. “So we’d always go out for drinks after class.” Apparently, neither Gaines nor Berry, both soft-spoken and thoughtful men, were the talkative, outgoing social animals that the other fellows appeared to be. “One night, Wendell came up to me and said, ‘I need to talk to you outside.’ This was the 1950s. When a white guy from Kentucky asks a black guy from Louisiana to step outside, you know what that means. I went out there expecting us to fight, but Wendell said, ‘Hey, man, we’re both Southerners. We’ve got to be friends. We’ve got to stick together.’”

A few months ago, I returned to Louisiana to visit Ernest and Dianne. Both Gaines and I have new books out this fall, and I wanted to celebrate with him. His novella, The Tragedy of Brady Sims, his first book of new fiction since 1993, unfolds after Brady Sims shoots his own son inside a courtroom after the young man has been convicted of robbery and murder. While Sims is holed up inside the courthouse, a young reporter heads to the barbershop in the African American section of Bayonne to dig deep into the community’s memories of Sims’s troubled life. Once again, Gaines has filtered a story through the place, the landscape, and the people he knows best. My new novel, The Last Ballad, follows a young textile worker who is swept up in a violent mill strike in the summer of 1929, after she takes a stand for herself and her children in joining a labor union. It should come as no surprise that the novel is set in my hometown of Gastonia, and is based on true events.

I landed at the airport in Baton Rouge and rented a car, and I marked the landscape as it changed from the urban center of Louisiana’s capital to the oil refineries along the Mississippi to the small town of New Roads, and finally to the flat farmland marked by corn, soybean, and sugarcane fields around False River. Gaines was waiting for me on the porch when I arrived. Aside from using a walker to get around due to a bad back, he had changed very little in the three years since I had last seen him. When he saw me, he smiled and rubbed his face, a gesture toward how white my beard had gotten.

“That’s what having two babies will do to you,” I said.

“Nah, man,” he said, “you look great.” I followed him inside and said hello to Dianne, and the three of us sat down to lunch. “I remembered how much you like red beans and rice,” she said.

We ate and they asked me about the things that had happened in my life. My wife and I had returned to North Carolina after she practiced law and I taught at a small college in West Virginia; we have two little girls under three years old; and I had been offered my own position as writer in residence. As the University of Louisiana–Lafayette had welcomed Gaines home in 1981, the University of North Carolina–Asheville had called me home to the mountains in the fall of 2016.

Our conversation turned toward our time at the university in Lafayette, and he asked about classmates I had kept in contact with, two of whom remain close friends. He remembered every story that each of us had submitted for class.

“I even remember the stories you submitted when you applied to the workshop,” he said. “You were writing about people I understood, about rivers and mountains and forests. I thought, Here’s a guy I can work with.”

That evening after dinner at a restaurant in New Roads, Gaines told a joke about a man who falls from a window in a tall building. As he plummets toward earth, the man notes each floor as he passes, saying, “So far, so good,” all the while getting closer to the ground. Gaines was already laughing by the time the man reached the first floor: “So far, so…”

There is a certain ceremony in dining with Ernest and Dianne Gaines. They know the owners of most of the restaurants in the area, and most of the waitstaff as well, and most of the diners know the Gaineses or at least recognize them. They say hello to everyone on the way in, and then everyone says goodbye to them on the way out. People still marvel at this man who left home so many decades ago only to return in a way that proved he had never truly left.

This is what I was thinking about as we climbed back into the car to head home, but I was also thinking about the ways in which my evolution as a writer and my literary career are inextricably tied to Ernest J. Gaines. I did my best to share with him what was on my mind: how I had discovered his writing back in North Carolina; how I had traveled to Louisiana to study under him; how I was now the writer in residence at the place I consider home because I learned to write about it after standing with him in an old cemetery fourteen years ago. I joked that perhaps it was a good omen that we both had books coming out at the same time.

Gaines laughed, and then he turned and gave me a quick smile.

“So far,” he said, “so good.”