Good Dogs

Five of the South’s Best Gundog Trainers

Few things can match the sublime pleasure of working with a great dog in the field. But the dogs don’t usually start out great. These trainers are here to help

Hollis Bennett

Puppy Love

Ronnie Smith and Susanna Love with a seven-week-old addition to their line of Brittany spaniels.

When it comes to our four-legged hunting partners, the potential to rapidly swing between the emotional extremes of adoration and apoplexy, pride and embarrassment, or satisfaction and regret begs for a kind of therapy session that begins with “So, tell me about…your bird dog.” On a chilly evening before a hunt, perhaps nursing a wee dram, we might watch our pooch curled up peacefully and feel the world aglow with goodness. But come morning, as our beloved sprints uncontrollably toward the horizon, oblivious to commands now fraught with desperation, we wonder which of us is crazier.

Your first step in the healing process is to admit that you need a trainer. Next is to locate one that’s suitable for you and the dog, which can be like asking a New Yorker where to find a good slice of pizza. Everyone has an opinion. The following professionals have decades of experience, and many consider them to be among the best gundog trainers in the South. They often specialize in certain breeds and methodologies, and their goal is to make you and the dog a team united in your passion to hunt birds, to rekindle the romance of the hunt—and, yes, to help you save face in front of your buddies.

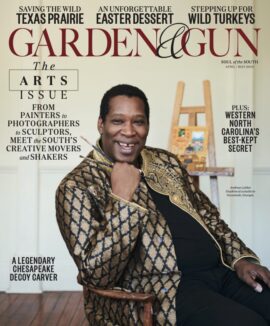

Ronnie Smith and Susanna Love (pictured above)

Ronnie Smith Kennels

Big Cabin, Oklahoma

Dog training runs deep in the married team of Ronnie Smith and Susanna Love. He hails from a dynastic bird-dog family, including his late father, the renowned trainer Ronnie Smith, Sr., and his uncle Delmar Smith, who’s now in the Field Trial Hall of Fame. She’s a fifth-generation West Texas rancher and grew up training horses and dogs with her mother, who also competed in field trials.

Andrew Hyslop

Ace, an eighty-year-old male.

Today, at Ronnie Smith Kennels, the couple work with all pointing and flushing breeds as well as breed and train a few litters of Brittany spaniels and English pointer puppies for sale each year. For Smith, the English pointer is a breed near and dear to his heart. “I’m a pointer guy,” he says. “We guide a lot of corporate and commercial hunts in Texas, and I find that the English pointer does better in a hot, high-humidity environment.” English pointers tend to be congenial in a way that belies their muscular physicality. People are often surprised by the breed’s intelligence and warmth, attributes that can make it a good house pet provided it gets plenty of exercise.

Based on his family’s decades of experience, Smith employs the Silent Command System of training, a “stair-stepped system” that ultimately builds physical points of contact on the dog’s body, such as touching the flank to honor another dog’s point and stay steady. The format, he says, builds confidence and is designed to produce a bird dog that “knows what to do in the field.” And if things don’t go quite as planned in the ever-changing conditions of a hunt, Smith keeps a maxim from Uncle Delmar in mind. “Always give the benefit of the doubt to the dog,” he says. “Just put yourself in the dog’s position when it’s trying to make a decision. Things may not be exactly what you expect they are.”—ronniesmithkennels.com

Andrew Hyslop

A Verein Deutsch-Drahthaar, nails a retrieve.

Todd Agnew and Christina Power-Agnew

Craney Hill Kennel

Mitchell, Georgia

“I don’t believe that a dog can do everything,” says Todd Agnew, who established Craney Hill Kennel with his wife, Christina Power-Agnew, in 1995. The couple specialize in training spaniels and breed English springer spaniels, and their philosophy emphasizes the individuality of the dog rather than forcing it into a role counter to its nature. Case in point: Not every gundog is meant for field trials.

“Essentially, the field-trial dog is a hunting dog with more pace, style, and excitement,” Agnew says. “It is a show, and you need a dog that can command attention, not just find birds. It needs to be able to show off.”

Compared with larger bird dogs, the quick English springer spaniels are a marvel to watch in the pheasant fields. Their medium-sized stature stems from their seventeenth-century breeding, which took them into dense cover to flush game birds and rabbits. But over the ensuing generations, the dogs have become prized for their soft mouth, retrieving skills, and bird-marking acumen in a range of settings.

Given the breed’s versatility, Craney Hill Kennel optimizes its grounds’ diversity of terrain, including woods and water. “If you run a dog in the fields first, not all dogs become comfortable in the woods,” Agnew says. “The woods are big and dark. A dog needs to get comfortable in the woods because the dense cover molds its behavior to hunt close.” And he emphasizes the importance of building bonds between owner and dog. “Everyone says they want a natural retriever, but they do not realize that a natural retriever makes the retrieve and runs off to eat the game,” he says. “We actually want an unnatural retriever that will put those instincts to work for us.”—craneyhill.com

Tracey Lieske

Wild Wing Lodge and Kennel

Sturgis, Kentucky

Andrew Hyslop

Tracey Lieske with a pair of young English setters at Wild Wing Lodge.

Call him crazy, but Tracey Lieske believes that gundogs develop better with wild game birds rather than the pen-raised fowl that dominate commercial wing shooting. He doesn’t base that conviction on some wide-eyed notion. His Wild Wing Lodge and Kennel is a twelve-thousand-acre wonderland of woods, grasses, and crop covers that’s home to a thriving population of indigenous quail. And those hard-flying birds are just the thing to bring out a dog’s prey drive and sharpen its skills.

“Our philosophy is to expose the young dog to all of the elements that Mother Nature has to offer, including numerous bird contacts,” Lieske says. “We’ve found that by doing this we build on the dogs’ natural pointing ability and desire, to produce a bird dog that has a lot of style and intensity around its game.”

For Lieske, the program is a big win for his English setters, a breed that loves to work but that he says typically matures more slowly than the English pointer. “English setters generally don’t mature until about two years old, and we’re seeing pointer-like performance from our setters at six to ten months old.”

Andrew Hyslop

Training Days

Lieske at work with setters Parker and Purdy.

In addition to training, Lieske also hosts quail hunters at Wild Wing Lodge during the season. Off-season, he trains in the mild weather of his Wild Wing Lodge North, on Clearwater Lake in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. And if you stick around, he offers prime grouse hunting during the month of October.—wildwingkennel.com

Martin Deeley and Pat Trichter

Florida Dog Trainer

Montverde, Florida

To e-collar or not to e-collar is one of the most polarizing issues in the bird-dog community. But for Martin Deeley and his wife, Pat Trichter, there is a middle ground.

A cofounder of the International Association of Canine Professionals, Deeley has been training bird dogs for more than thirty-five years, starting in his native England, where most hunters and field-trial handlers prefer positive-reinforcement techniques. It was somewhat of a rude awakening for the couple when they arrived in Dallas in the late 1990s to find that e-collars ruled. Eighteen months later they left for rural Florida, where Deeley developed a system that bridged American and British training traditions. Called E-Touch, the idea is to use an e-collar’s lowest possible voltage only to get the dog’s attention rather than transmit correctional jolts, and it works in conjunction with a system of reinforcement. “E-Touch supports what I train,” Deeley explains, “which is the British style where the retrieve is intrinsic to the reward. Dogs know when they do a good job, and they understand your body language when you tell them what a good job they have done.”

At their kennels outside Orlando, both Deeley and Trichter train companion dogs while Deeley focuses on Labrador and golden retrievers—or any other retriever breed—for wing shooting. “Labrador retrievers are the easiest dog I’ve ever worked with because we both enjoy what we’re doing,” he says. “You’re rewarding their innate abilities.”

Whether it’s a golden or a Lab, finding a great retriever requires basic detective work. “If they’re show dogs or heavier dogs, they don’t have that hunting drive,” Deeley says. “You want a retriever that comes from good, working bloodlines.” And given their ingrained work ethic, he says, “my approach is that if the dog isn’t doing its job, then I must’ve done something wrong. And then I’ll look for a solution.”—floridadogtrainer.com

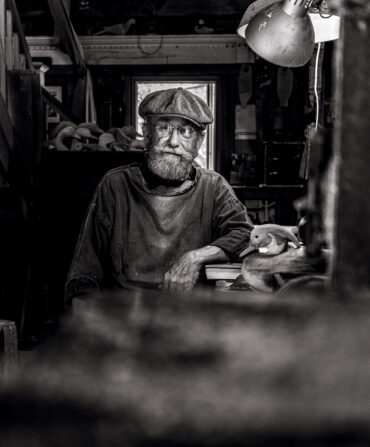

Robert Milner

Duckhill Kennels

Somerville, Tennessee

Andrew Hyslop

Robert Milner cozies up with his pupils.

A retired U.S. Air Force lieutenant colonel, Robert Milner is no stranger to discipline. But duck hunters who pay a visit to his rural kennels might be surprised by what they don’t find: not an e-collar in sight. Milner is a stalwart advocate of positive-reinforcement training for gundogs.

Beginning in the 1960s, Milner trained thousands of dogs using standard compulsion methods (shorthand for aversive training techniques such as e-collars). His turning point occurred following the 9/11 attacks, when FEMA dispatched the Tennessee-based search and rescue team Task Force One to the Pentagon crash site to find survivors in the rubble. The rescue dogs’ performance proved disappointing, and Milner got the call to overhaul the training regimen.

He opted for a new paradigm inspired by the U.S. Navy’s Marine Mammal Program and the principles of operant conditioning, a form of positive reinforcement training in which a correct response is rewarded while a wrong response is ignored. And he made another key change as well. “The dogs were lacking in hunting persistence,” he says. “They didn’t do well, because they were trained and maintained on a constant schedule of reinforcement.” Instead, Milner employed a variable schedule, similar to what happens in nature. “Studies have shown that a lion is successful on about one stalk out of five,” he explains. “It keeps the lion hunting.”

Andrew Hyslop

Brown-Eyed Beauty

Cuckavalda Monty (Tex), a five-year-old British Labrador retriever.

He was able to reduce prep time for the task force’s dogs from eighteen months to six, and if it could work for rescue dogs, he was sure it could work for bird dogs as well. By now, he was a frequent visitor to the United Kingdom, where field-trial handlers prized British Labrador retrievers for both their hunting drive and their gentle disposition and receptiveness toward soft-handed training regimens. They were such a good fit that Milner has since become the only American breeder of British Labrador retrievers from the original lineage of the fifth Duke of Buccleuch of the 1830s.

“With punishment, whether it’s with a choke collar or a shock collar, it makes the dog want to run from you,” he says. “We have to adopt more humane ways of training our best friends.”—duckhillkennels.com