Land & Conservation

How One Arkansas Family Is Rewriting the Rules of Rice Farming

In flooded fields amid a waterfowler’s paradise, the Isbells are reimagining how to use the land—and gaining the attention of sake brewers worldwide

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

Arkansas old-timers will tell you that the ducks know where the old sloughs were. That even today, when half the woods have been cut down and turned into mile after mile of flat, featureless rice and row-crop fields, the location of those ancient, winding creek bottoms remains imprinted in their brains. That’s one explanation for why one rice field might be full of ducks when adjacent fields are empty, even though they all look similar. Somewhere in the twisted strands of those birds’ DNA, they know where those ghost bottoms are.

I ask Chris Isbell if he agrees with this as we sit in his muddy gray pickup and watch ducks pour into flooded timber just beyond an Isbell Farms rice field. What Arkansans call a “rice field” is really a flooded field, diked and pumped full of shin-deep water. Isbell is a fourth-generation farmer in Central Arkansas and a second-generation rice farmer, and his family farm sits in the middle of the state’s Bayou Meto, Big Ditch, and Two Prairie Bayou bottomlands. It’s perhaps the finest stretch of rice-growing country in the South, and it is, for sure, among the region’s most famous waterfowling grounds.

Isbell looks out through the windshield, leans back, and laces his fingers behind his head. The longtime farmer, still boyish at seventy, wears rectangular glasses and a blue Columbia fishing shirt. He also frequently flashes a playful grin, as if he’s thinking about a joke that he’s not sure you would get. He’s not the kind to give you an answer off the cuff.

“I do,” he finally replies. “That’s why we put the duck pits where those old sloughs ran. They know. They remember. It might be a mystery to us, but it’s no mystery to the ducks.”

As with those ducks, Isbell’s interest in the past seems rooted in what it can tell us about the present, and more important, the future. Isbell has devoted much of his working life to transforming rice culture in the South, making it more environmentally friendly and supported by diverse streams of rice-adjacent income so that farmers can keep farming. His approach isn’t to proselytize but to lead by example, and on the three-thousand-acre Isbell Farms, he and his family have stretched the boundaries of what it means to be a rice farmer.

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

Pintails leave an Isbell Farms impoundment; fourth-generation farmer Chris Isbell stands in a rice field at his family’s Arkansas farm.

Some of Isbell’s ideas veer off the main road. Eradicating weed seeds with microwave transmissions, for example. But others have proved prescient. The Isbells were early adopters of more sustainable rice cultivation methods such as alternate wetting and drying, which reduces both water use and methane emissions significantly, leading to their becoming part of a small group in 2017 of the first American rice farmers to sell carbon credits, to Microsoft. Such practices enabled him to cut water use in his fields by half, and explain why he partners with university scientists to find ways to further reduce emissions. Coming up with wild-eyed ideas about rice farming is why Isbell Farms attracts scores of agricultural officials and researchers to this chunk of Arkansas to ogle just what the heck Chris Isbell is up to now. And why he and his family are minor celebrities in Japan. We’ll get to that last one in a minute.

To understand Chris Isbell requires a grasp of the long-intertwined relationship between rice farming and duck hunting. The country’s leading rice-growing state, Arkansas produces more than 40 percent of U.S.-grown rice. For decades, Arkansas rice was cultivated the same way it’s grown in the Far East—on terraced and leveed fields where farmers can manipulate water levels. That’s still the practice across much of Arkansas and other states.

But growing rice that way requires large amounts of water. Managing water on terraced fields also requires enormous amounts of off-season labor—building terraces, fixing terraces, leveling fields, and cleaning out ditches—which also takes enormous amounts of fuel.

In the 1970s, Isbell’s father, Leroy, pioneered a different way to grow rice. By leveling fields completely flat, water could be managed field by field, instead of terrace by terrace. It’s called “zero-grade farming” and uses nearly a third less water than traditional terraced methods. And because the rice fields can be kept flooded after harvest and throughout waterfowl migration and wintering periods, it also creates some of the finest waterfowl habitat on the planet.

Wins on top of wins, which is sort of an Isbell thing. Not that it’s always so straightforward or successful. Folks around Carlisle, Humnoke, and Snake Island have gotten used to the farm’s experimental ways, like the fields of filamentous algae Isbell raises that provide mulch for his rice fields, or the towers and monitors along some of his fields that measure emissions. But nothing compares to the chaos that ensued when word got out that the Isbells were growing Japanese rice. “There were Greyhound buses driving down our rice levees,” Isbell recalls with a grin. “It was crazy.”

That mania stemmed from a 1987 meeting of rice researchers in California, where Isbell chatted up a Japanese economist who explained in somewhat nationalist terms the difference between Japanese and American rice. As Isbell remembers him saying, Japanese rice was an elevated grain, bright on the tongue and silky smooth. American rice, by contrast, was simply a glop of stuff to which butter or gravy adhered. When the economist told Isbell that Japanese rice would grow only in Japan, the planter got his back up.

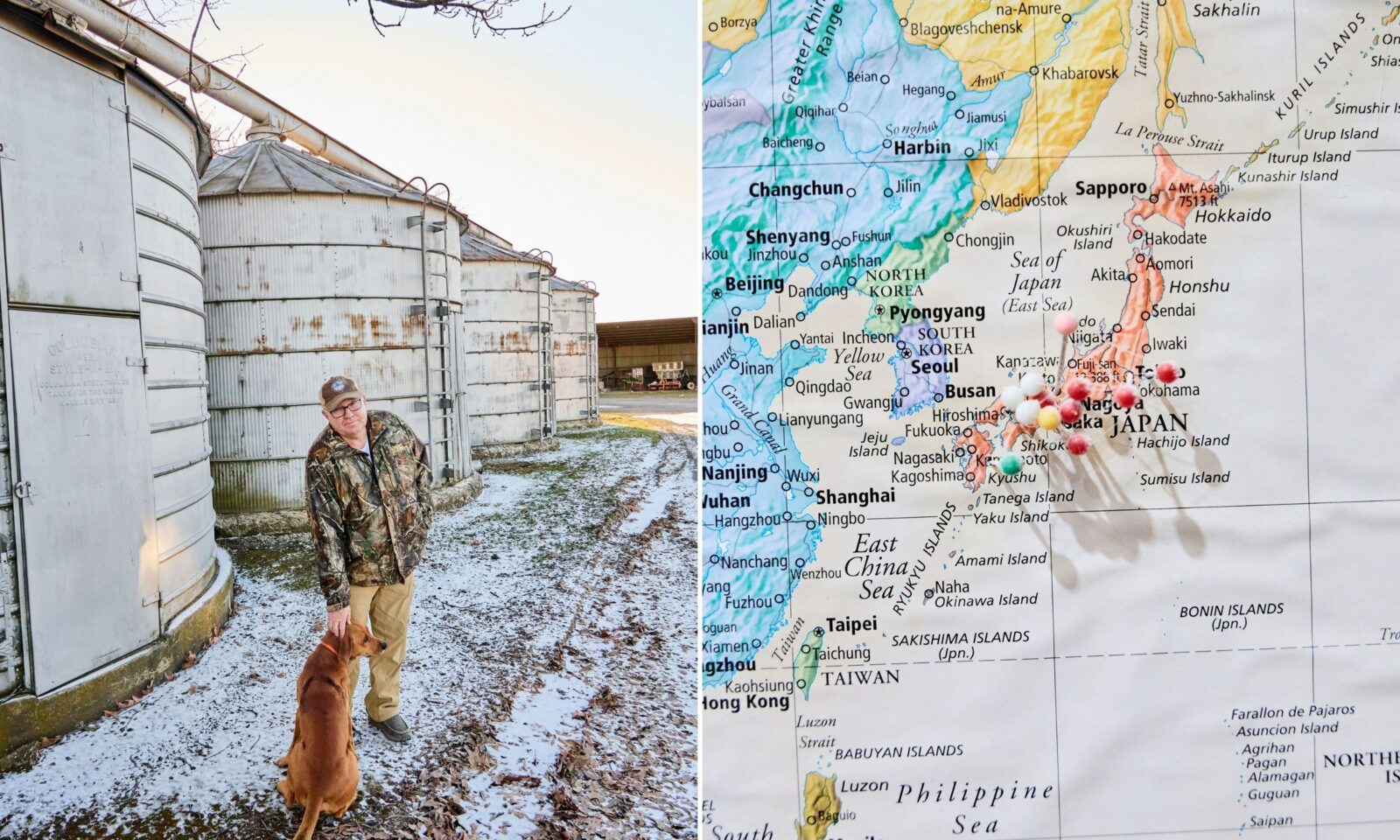

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

Chris Isbell with one of the farm’s dogs; pins mark the home locations of Japanese visitors.

He went home and pulled out a globe. “This was before Google Earth, when people actually looked at globes,” he says, smiling. He noticed that the region of Japan known for Koshihikari rice was situated on almost the same latitude as his rice farm. Koshihikari is a short-grain sticky rice cultivar beloved as both table rice and premium sushi rice. After three years of tinkering, Isbell sowed his first fields with Koshihikari, quite likely the first planting outside Japan.

It took three more years to bring the rice to the American market, but it caused quite a stir. Japanese media went bonkers when they learned that an American farmer had cracked the code of what was essentially a culinary state secret. Japanese news outlets picked up the story, and a Japanese television station produced a ninety-minute documentary. Scores of reporters hounded the family, and Japanese tourists and farmers, as well as public officials from around the world, started pouring into tiny Humnoke.

Then came the next hurdle: selling American-grown rice to Japan. The country had long banned rice imports but at the end of 1993 agreed to incrementally open its markets to foreign producers. Isbell was one of the first farmers to send American rice to Japan, and he and his wife, Judy, received an invite to travel to Sendai City to speak at a conference. It was a tense time. Protesters crowded the streets. The auditorium, Isbell recalls, hummed like a beehive.

The Isbells took the stage and told their story. They showed a slide presentation of the farm. The Japanese attendees were aghast at the size of their fields. “A lot of them were growing rice on two acres,” Isbell says. “It was a little bit different.”

When they began taking questions, the first man to stand up was visibly angry. He railed into a microphone as Isbell awaited the translation. “He said, ‘My seventh-grade son says Japan is self-sufficient in rice. Why should we buy rice from the United States?’ And he pointed right at me.”

On the auditorium stage, Isbell took an Isbell moment. I can almost imagine him leaning back, fingers laced behind his head.

“I thought to myself, Man, I guess I got to say it. I said, ‘I’m very sorry, and I don’t mean this to be ugly, but the United States is actually self-sufficient in automobiles.’”

The crowd was silent as the translator worked through the language. Isbell was sweating. Then the convention hall broke out in laughter. Isbell rice went on sale in Japan the next year. Sold as “Chris’s Rice” or “Rice Ambassador,” the bags featured a photograph of the family and glowing language about Arkansas, “where golden ears of rice stretch to the horizon.” Isbell and Judy have since visited other countries, and Isbell has returned eight times to Japan as an ambassador of American rice farming.

Around a large table in the Isbell home, family members howl with laughter. An impressive collection of musical instruments hangs on the walls. Isbell plays the mandolin, guitar, and banjo. Most of the family—Chris and Judy; their daughter, Whitney Jones; her son, Harrison; and her daughter, Alayna—perform often at church. We pass platters of lasagna and pitchers of sweet tea as the crowd recalls the farm’s weird brush with global fame.

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

Stalks of growing rice; a bird’s-eye view of rice harvesting.

The Isbell family may not quite be a dynasty, but they are consumed with rice through and through. Judy is a constant presence with Chris at conferences. Whitney runs the farm’s significant community outreach and social media efforts. Her husband, Jeremy, is an Isbell Farms partner and Rice Farming magazine’s 2023 Rice Farmer of the Year (Leroy and Chris were jointly named Rice Farmers of the Year in 1996; both are Arkansas Agriculture Hall of Fame inductees). Nephew Shane Isbell and his wife, Lisa, work on the farm, as does Harrison. The only direct family member absent this day is Chris and Judy’s son, Mark. He serves on the USA Rice Sustainability Committee and had to skip dinner because he is in Costa Rica spreading the gospel of Isbell-style rice farming.

In the crush of attention as word spread in Japan about the American farmer growing Japanese rice, so many visitors arrived that Whitney and Mark made summer money leading tours. Once, the front doorbell rang, and Judy answered it. Two men in black suits stood on the porch holding a Panasonic rice cooker. The president of Panasonic had seen the documentary, in which the Isbells had used a rival’s brand, and emissaries had come to ask a favor: Next time you’re on Japanese television, please use our rice cooker instead.

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

Isbell Farms partner Jeremy Jones; freshly harvested rice waiting to be hulled.

The family learned a number of important lessons, about the power of media and about the opportunity—and the need—to shape the story told about family farms in America. Whitney, in particular, is passionate about connecting with customers, people who stumble across the farm through social media, and curious locals who remain surprisingly uninformed about Arkansas’s agricultural heritage. “It’s about educating people about real life on the farm,” she says. “Whatever it takes.” Not long ago, while shopping in Little Rock, she mentioned to a lady at a store that she was a rice farmer. “How does that work?” the lady asked. “Does rice grow on trees?” One Instagram post about the Isbells’ farming was shared twenty-one thousand times. “It had three thousand comments,” Whitney says, “and I answered every one. I don’t care if people even say something ugly. I say something nice back, because that drives the algorithm, and that drives engagement. And I just want people to see and understand what we’re doing out here and why it matters.

“Now,” she says, eyeing my plate, “did you want another piece of cake?”

“Oh, this one is going to mess us up,” Shane Isbell growls. “You just watch.”

We are working a group of a half dozen ducks on their second pass over an Isbell Farms timber hole. As Shane chatters to the birds, I press my face to a tree trunk. It had been a textbook play, the mallards bombing out of a blue sky, circling the decoys in a tightening gyre. But as they turned a corner on their looping flight, a single mallard hen joined the group, slipping in from nowhere. Instantly, the vibe shifted in the little flock. The birds picked up their heads and gained a few feet of elevation. Now they turn for another circle but are hesitant to close the distance. We see that hen on the outside of the flock, dragging the rest of the birds with her. This late in the season, mallards are already pairing up. The last thing a girl duck wants is a bunch of dudes pestering her to death, and we have a bunch of plastic dudes spread out on the water.

“This time of year,” Shane mutters, “the hen holds all the cards.” The birds drift off in the interlocking matrix of tree limbs and head for elsewhere. But my pounding heart also suggests how the scene is a perfect example of the thrill of timber hunting in Arkansas, whether triggers get pulled or not.

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

Shane Isbell on a duck hunt; ducks circle over a frozen impoundment.

It has been a century since the symbiotic relationship between rice farming and duck hunting in the state took a consequential turn. In 1926, a farmer named Vern Tindall built a reservoir on 450 acres of forested land on his farm near Stuttgart. He intended to use the water to irrigate his rice fields. He didn’t realize how many thousands of ducks would pile into his flooded timber. The rise of rice planting in Arkansas in the decades that followed saw thousands of acres of bottomland woods turned into so-called “greentree reservoirs” for irrigation, with a latticework of ditches, canals, and water-control structures connecting them. Duck hunters packed the reservoirs. “Timber hunting” for ducks became the ne plus ultra of waterfowling experiences in the South. And the region around Stuttgart took on a glamorous luster among waterfowlers. As the mallard flies, Stuttgart is about a dozen miles from the Isbells’ farm.

I’ve hunted ducks on Isbell property for more than a decade, making an annual January pilgrimage to the Snake Island Hunt Club, some of whose duck blinds stand on land that Isbell’s great-grandfather owned and farmed. There are dozens of duck clubs within a few miles, from family affairs to highfalutin outfits with dues and fees that would give Midas pause. The Isbell property hosts four different clubs alone, but none are of the fancy variety. “I like regular people,” Isbell says. “I like to help regular people who love to hunt get to hunt.”

Leasing land to duck hunters provides another income stream for the farm, but it also gives the family a meaningful way to stay rooted in the community and Arkansas tradition. From this perspective, rice on Isbell Farms is one kind of crop. The ducks in Shane’s timber hole are a different kind of harvest. The smiles on the faces of hunters and the memories made on the land are another. The chance to connect the experience of the American farmer to the nonfarming public is yet one more bonus. Whatever it takes, as Whitney Jones says. This family doesn’t let opportunity slip by, which is why they’re also at the forefront of another burgeoning rice venture.

At a workshop bench in a tall processing facility a few miles from the house, Chris Isbell spreads out a thin layer of newly milled rice grains. He picks one up, and I look closely: Perched on his fingertip, it looks like a tiny egg.

“Now let me show you something,” he says, using a razor blade to split the grain in half. “See that little line?” he asks. It is an even tinier pearlescent orb suspended in the grain like an egg yolk. “That’s what they’re after.”

That line is called shinpaku, the “white heart,” he explains. Starch is the main component in all rice types, but for high-quality sake, brewers prize cultivars that contain this line of pure starch in the center of the grain. Isbell Farms mills sake rice down to as low as 23 percent of its original size to create a premium product for brewing.

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

Grains of premium sake rice; harvesting at the farm.

The rice on Isbell’s workbench is a cultivar called Yamada Nishiki. That he is growing in Arkansas what is known as “the king of sake rice” is another by-product of his incessant tinkering. Isbell has long “played around” with various types of rice in a small four-acre plot near his house. He might grow forty varieties at a time, nursing them throughout the summer, taking notes. One day, he is fond of thinking, one of these might be something. He’d experimented with growing a little Yamada Nishiki, grains of which he’d kept in a freezer since the nineties. He’s not sure how the Takara Sake brewery in Berkeley, California, found him, but find him it did, and Isbell Farms began growing the rice commercially.

For five years, Isbell sold a bit of Yamada Nishiki to the California sake brewer. But as sake began to enjoy a global rise in popularity, that “one day” he’d wondered about came to pass. Isbell Farms started shipping the prized rice to breweries worldwide—in Mexico, Canada, Norway, and New Zealand. Its reputation grew, and Isbell soon partnered with Ben Bell, a native Arkansan and wine connoisseur turned sake aficionado who spent two years as a sake brewer in Japan and has a dream of turning the state’s rice belt into a sort of Napa Valley of sake. In 2023, Bell, with business partner Matt Bell (no relation), opened Origami Sake in Hot Springs, Arkansas, combining the town’s famed water with Isbell’s Japanese sake rice. The sake has won several awards, and it appears that Isbell has tapped into another growth sector. According to the Sake Brewers Association of North America, about two dozen craft sake breweries now operate in the United States, having more than doubled in number over the past decade.

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

Duck calls and other family memorabilia displayed in a glass-top coffee table; a selection of sakes that use Isbell Farms rice.

The Isbells’ sake exploits added yet another revenue stream and garnered a new round of attention. But for one of the most innovative and engaging farming families in the South, it’s all just part of another day on the farm.

When Isbell was in his mid-twenties, pondering the changing future of farming and how on earth he could make a decent living from the land, he learned that a biological supply distributor in North Carolina would buy frogs. Collecting frogs wasn’t exactly farming, but a dollar is a dollar.

He called the company and asked: “How many frogs do you want?”

We’ll take all you can get, came the reply.

Chris Isbell is an honest man. “You might want to think about that,” he said.

He shipped out hundreds of frogs. Then the company asked: What else can you catch? Can you catch spiders?

Watch this, Isbell figured.

He put his kids on three-wheelers, wielding PVC pipes with a washrag wadded up on the end. They zipped up and down the field edges, looking for large yellow-and-black garden spiders. “You’d bring that washrag up through the bottom of the web and wind it up, and there would be your spider on the end of the stick,” he recalls. Tap the stick on a five-gallon bucket filled with rubbing alcohol. Nothing to it. “Thirty-five cents a spider,” he says with a chuckle.

Next it was six-inch-long carp, caught in crawfish ponds and frozen in buckets. He met the buyer and turned over five buckets of frozen baby carp. “And he gave me seven hundred and fifty dollars,” Isbell says. “I felt like I’d robbed him.”

Isbell tells these stories one afternoon as we pull into a field while he scrolls through his phone, looking for a file dubbed “Projects,” where he types notes for all his wild ideas. Like spraying his rice with some kind of horticultural sunscreen—which may or may not even exist yet—because rice doesn’t care for certain wavelengths of ultraviolet light. Or using drone-mounted thermal imaging to assess how many insects are in a field to fine-tune and minimize pesticide use. Would that work? “Those bugs have blood in them,” he says. “They’ve got to be hotter than the rice.”

Crazy ideas about how to make a farm work in a fast-changing world. Like smashing a rice field as flat as a pancake. Or raising Japanese sake rice in the delta bottoms of Arkansas. Crazy ideas, and Isbell knows it. That stuff will never work, they tell him.

There’s that enigmatic smile again. Watch this. And hold my sake.

T. Edward Nickens is a contributing editor for Garden & Gun and cohost of The Wild South podcast. He’s also an editor at large for Field & Stream and a contributing editor for Ducks Unlimited. He splits time between Raleigh and Morehead City, North Carolina, with one wife, two dogs, a part-time cat, eleven fly rods, three canoes, two powerboats, and an indeterminate number of duck and goose decoys. Follow @enickens on Instagram.