Arts & Culture

Jericho Rising

How the push and pull of the South feed Louisiana native Jericho Brown’s soul-shaking, award-winning poetry

Photo: Audra Melton

It’s 9:00 p.m. and the poet Jericho Brown is singing Whitney Houston in a crowded bistro.

“Ohhhhh, I wanna dance with somebody,” he croons. “I wanna feel the heat!” Brown grins, shimmies in his seat, takes a messy bite of his hamburger. Asked if he watched the recent Houston documentary, he nods.

“Yes, God, and I cried the whole time. I was like, how did she not have anybody?” Brown swallows, takes a long swig of water. “There is not a day that I don’t talk to a poet,” he says. “This is what I mean when I say I don’t feel lonely anymore.”

Poems by Brown, who at forty-three years old is the director of the creative writing program at Atlanta’s Emory University, have been published in the New York Times, the New Yorker, the Paris Review, and Time magazine, among other prestigious spots. His third collection, The Tradition, has received rapturous praise—the book was already in its second printing shortly after its debut—and was named a finalist for the 2019 National Book Award for poetry, and one of the year’s “Books All Georgians Should Read” by the Georgia Center for the Book.

The poet and playwright Claudia Rankine says that to read Brown’s work is to “encounter devastating genius.” And indeed, his poems are sly buds that bloom on the page, bouquets of rage, wit, sorrow, lust, and earned wisdom. “Jericho is sui generis,” says Ilya Kaminsky, himself a celebrated Atlanta-based poet with a long list of accolades to his credit.

Kaminsky recalls being introduced to Brown in a tiny apartment in California. The two now talk every week, often touring together on the literary superstar circuit. “I have met many talented writers, some very famous,” Kaminsky says. “But one can tell right away when a person is an original, an individual. There are maybe four or five poets in the world who are as talented as Jericho is. And no one is more talented.”

In person, Brown is an explosion of life, magnetic, boisterous, a one-man carnival ride. Simply put, there is no scenario where one would be unaware that Jericho Brown is in the room. His laugh alone is a marvel—loud, sudden, shameless, as startling as a jack-in-the-box.

Brown says The Tradition is ultimately about the normalization of evil and contains the finest poems he’s ever written. “It’s the best example of my soul on earth,” he explains. “A representation of myself, but the better me, the bigger me.”

A better, bigger Brown is tough to envisage. A recipient of fellowships and awards from the Guggenheim foundation, the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard, the Whiting Foundation, and the National Endowment for the Arts, Brown has already hit the poetry world like a heat-seeking missile, his impact and import as large as his warm, open, Southern persona.

“In my family, you couldn’t be sullen,” he recalls. “You needed to be a person who would speak to everybody in the room, shake their hand, make a good first impression. It was important to my dad that you do what he used to call talk up.”

Brown was christened Nelson Demery III, and raised in the neighborhood of Cedar Grove, in Shreveport, Louisiana. The son of Nelson Demery Jr., a deacon and the owner of a landscaping business, and Neomia, a schoolteacher, Brown sang in the youth choir at Mount Canaan Missionary Baptist Church (his younger sister, Nequella, was on the usher board), a spiritual devotion that did not preclude Brown’s acting out in school. “I was always fighting, having trouble with teachers,” he says. He cycled through five elementary schools, two middle schools. “It wasn’t until I transferred to a magnet school that I started getting my stuff together.” Brown assumed he was just a sensitive, emotional kid with control issues. “But I know now, because of therapists, that I was acting the way my father acted at home.”

Brown describes his father as “wild” and unpredictable. He says there were outbursts and physical altercations—violence his parents have denied—designed to bring Brown to heel in ways that could never succeed. “Being gay is something my parents think is their responsibility to confront,” he says flatly. “Anything that would embarrass them publicly they were not interested in.”

According to Brown, his parents wanted him to become a lawyer or a doctor because those professions would reflect well on “the work they had done to create me and to raise me. When my dad figured out that I was not going to go to law school, he didn’t speak to me for over a week.” When Brown told his parents he was gay, they said, he recalls, “Okay, well then you’re not our son.”

The rift is one reason Brown eventually changed his name. “I wanted the poems to be mine.” He also knew his family would most likely be wounded by some of his writing, and he wanted to spare them any further discomfort. “In retrospect, and I’ve thought about this a lot lately, my parents were raising a black son and they just didn’t want him to go to prison, didn’t want him to be unemployed. They wanted to create a person they could be proud of. So it didn’t leave a lot of room for me to make mistakes, you know?”

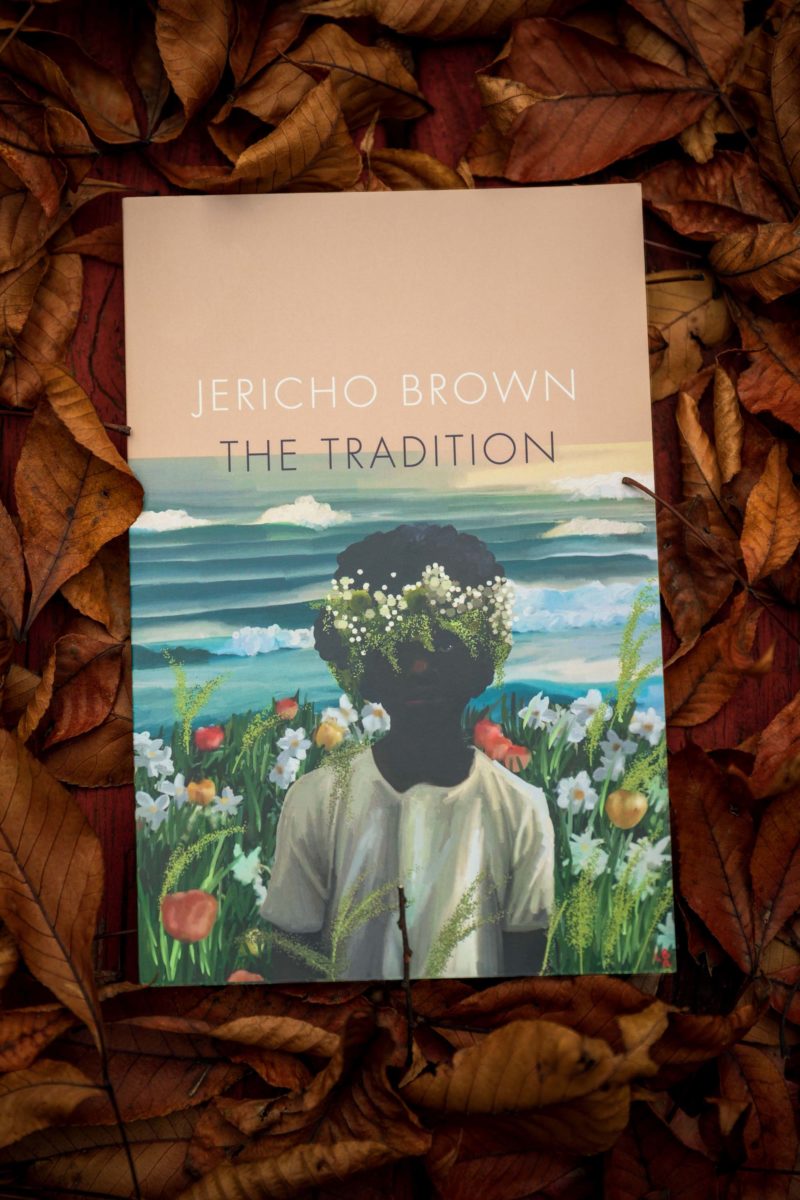

Photo: Audra Melton

Brown’s latest collection, The Tradition.

Brown and his parents have since reconciled, if uneasily. Boundaries have been set, certain topics avoided. “They’re older now,” he reflects. “Really, they just ran out of energy. I think they have agreed that I’m a lost cause.”

Brown shrugs and smiles, seemingly at home with his given designation as the perpetual family frustration—a burden he’s abided since he was a young man gravitating toward rhyme. Back then, he was enchanted by song lyrics, especially those about people in love. Then he read the poem “Edge,” by Sylvia Plath. “It was the first time I had ever seen the modifier broken from the noun,” he says. “‘Her bare / feet.’ You had to move your eyes to the next stanza. And I could not deal with it. I thought it was the most beautiful thing. I mean, it was so small and slight. And I felt completely cut open by it.”

Brown then moved on to A. E. Housman, “who I didn’t know was gay, but somehow must have been speaking to me from that.” In college at Dillard University in New Orleans, Brown immersed himself in the words of Frederick Douglass, “a right mother******. When he would give speeches, the abolitionists on tour would be on a wagon and he would have to walk behind the wagon because he was black. Isn’t that crazy? And he could write better than any of them bitches.”

Not long after, Brown found the poet Essex Hemphill. “Hemphill was really the root for me. I must’ve been nineteen. I remember being in the library, reading Ceremonies, and I had this feeling that was so exhilarating and exhausting and scary because this book was telling all my business.” Brown recalls trying to hide himself from view, make himself tiny. “I didn’t want anybody to see me reading this book of secrets because then they would see my face and know that it was my secret.”

Brown calls himself rebellious, a defiance born of being black and gay in a culture hostile to both. Part of that rebellion saw Brown taking on musty poetic conventions, inserting himself (like Plath, Douglass, and Hemphill) where many didn’t believe he belonged, then mastering his craft to the point of irrefutability. “Thomas Jefferson argued there was no poetry among black people,” Brown says. He decided that if formality was going to be the obstacle, he would first master, then dismantle, the form. “Jericho is a supreme formalist,” Kaminsky says. “It took people years to notice he is just as fancy in his craftwork as any American poet of his generation. But he also understands the power of human emotion, and he knows how to modulate it so that the reader remembers the poem years after it was read.”

A natural showman, Brown leans toward dazzle. His artistic voice, like that of his beloved Whitney Houston, is a thing of such transcendent beauty and honed skill it changes anyone lucky enough to hear it. Like the note he used to keep over his computer: Every line a surprise.

In The Tradition, Brown showcases an entirely new poetic form he calls the duplex, which draws from the ghazel, the sonnet, and the blues. Via a specific repetition of lines, arrangement of couplets, and number of syllables, Brown invented something wholly original that challenges and enlivens older formats. He took a weaponized form, subverted it, thumbed his nose at the gatekeepers, and did them one better. “I wanted to make something that sounded elegant no matter what,” Brown explains. “I also wanted a form that had all these identities in it. I wanted a form that in my head was black and queer and Southern.”

Brown welcomes contradiction and complexity. His brain is jazz, a whirlwind of associations and inspirations. The duplex, like its namesake two-doored home, provides the idiosyncratic architecture.

“My dad felt you could talk people into anything, you could smile people into anything, you could charm people into anything,” Brown says, wistfully. “I don’t know that it is useful for me to romanticize ideas about what poetry can do in the world. But I do believe, because I know what reading a poem can do to me, that a poem can change a life.”

Photo: Audra Melton

Brown’s creative process includes arranging potential lines he has typed on strips of paper into poems.

Brown’s basement library is filled with poetry books. There are also comfortable chairs with cozy afghans folded on top, and a Diana Ross doll he was given as a fortieth birthday present by the poet Phillip B. Williams. No fewer than six Bibles line one shelf, arranged neatly in descending height.

In the kitchen, a tower of prepared food boxes teeters alongside Kind bars and mature bananas. Brown has been touring with The Tradition every day he isn’t teaching. “I read at Xavier University. The night before that, I read at my alma mater, Dillard University. Tomorrow, I’m headed to D.C. Monday I’ll read at the University of Baltimore,” he says, describing a typical breakneck week.

The demands of his tour permit little time for luxuries like cooking or sleep. Not that Brown sleeps much anyway. He often writes at night, calling his poet friends at 3:00 a.m. to read verses he thinks have potential. “Poets always answer the phone,” he says with an emphatic nod. “That’s a fact.” Sometimes Brown tweets in those onerous, inert hours, sharing his anxieties and fears, open to connection however it comes.

“I look like a crazy person when I’m writing,” he confesses. “It’s four in the morning, I’m wandering around in my underwear, pacing between my basement and my living room, chanting to myself. In order to get a poem to work on the page, I have to hear it in the air. I’m always reciting lines, testing to see what they sound like, then running to the computer.”

On parts of Brown’s basement floor, Ziploc bags stuffed with strips of paper roll around like tumbleweeds. On each piece of paper, Brown has typed a potential line for a future poem. He groups them by category—every line that mentions a “mother” in one bag, every line in iambic pentameter in another, and so on. It’s a strategy for memory keeping, for never having to face the dreaded blank page. Asked the moment he became a poet, Brown doesn’t hesitate.

“When I was in fifth grade and my teachers were talking about the Civil War and they said we ‘lost.’” He howls, claps his hands against his thighs. “Hmm…did we? Did we lose? It didn’t seem that way to me.”

Brown was already hip to the cost of difference, aware of the ache, the dissonance that comes from living in the presumption of “we.”

“People have these assumptions about how hatred works in the South,” he explains, noting that even among enemies, Southerners identify with each other, they remain in relationship, like circling planets. “There’s an understanding that somebody is with you even if you hate them, which is very different from Boston or the West Coast, where they act like they don’t see you at all.”

And though being “seen” in the South was and remains a risk for Brown, it is the only place he longs to be. “The literal engine of my poems is the vernacular of the South and in particular black people in the South. I need to be around the number of black people that the South provides, the expectation of seeing black people that the South provides, the relationship black people have to each other that the South provides. That’s definitely not available in San Diego.”

That very lingua franca, delivered in his seductive Louisiana inflection, is part of what lifts Brown’s readings to the level of sacred experience. “I have seen people cry, laugh, and then cry again,” Kaminsky says of Brown’s performances. So profound is his gift for writing, for oratory, that hearing Brown recite his work is akin to hearing a sermon in a language you didn’t know you knew. (No wonder his friends answer his 3:00 a.m. calls.)

“We want from art the same thing we want from God,” Brown says. “To be changed.”

Photo: Audra Melton

Brown in the Cator Woolford Gardens.

Tonight, Brown is giving a talk at a bookstore in Decatur, Georgia, not far from his house. The book club event takes place upstairs, where Brown slides into a seat at the top of a circle of chairs and gamely initiates small talk with the gathering of about a dozen middle-aged white people. The audience is nervous, the setting intimate, but Brown puts them at ease. “I learned I had an accent when I moved to the West Coast,” he quips, throwing his head back and laughing loud enough to be heard from the bathroom downstairs. By way of introduction to his collection, he describes himself as “a black man who thinks a lot about flowers,” sharing that as a kid he did so much yard work for his father’s landscaping business, he “could clean out all your beds, if you wanted.”

The audience chuckles politely, then Brown launches into a reading of his poem “Foreday in the Morning,” which opens with a line about his mother growing morning glories, “because she was a woman with land who showed as much by giving it color.”

The poem continues, unpacking racism, the futility of and essential need for beauty, the damage of mythology, of embracing a dream that’s actually a trick, the poison of drinking someone else’s idea of yourself.

I’ll never know who started the lie that we are lazy,

But I’d love to wake that bastard up

At foreday in the morning, toss him in a truck,

and drive him under God

Past every bus stop in America to see all those black folk

Waiting to go to work for whatever they want…

When Brown finishes, the woman on his right says the poem made her sad. Downstairs pop music blares, the bookshop having chosen not to turn it off. The empty lyrics and pounding beat compete with Brown as he reads more selections. If it bothers him, he doesn’t let on. Instead, much as his poems do, he extends grace to those who may or may not deserve it.

As he does at every event, Brown introduces this evening’s listeners to forgotten, unexamined pockets of themselves, unearthing the hidden parts neglected or denied, an experience akin to dipping into a hot bath that first makes you gasp, but soon soothes you into an indispensable calm.

Another woman asks how Brown writes his poems, says she too is a poet. Brown walks her through his process, how he pushes forward from lines he collects like souvenirs, tucking them away until he’s moved to take the most compelling and anchor it at the bottom of the page, then take the second most compelling and plant it at the top, before engaging the two lines in conversation. Brown retrieves his phone and begins to read a few snippets he’s gathered recently.

“In Kansas, children have to take field trips to slaughterhouses.”

“They asked us what we were doing and we said fighting because that was the answer.”

“What does it mean to italicize someone’s name?”

The audience swoons, feeling rightly that it has been let in on a captivating secret. And the listeners begin, as humans always do, to build a narrative between the random lines.

“It’s not a two-plus-two-equals-four situation,” Brown explains. “If you want to write poetry,” he warns as the night wraps up, “you have to be in it for the long haul.”

The event has ended and Brown is driving home, the radio playing too softly to register over his booming voice. He’s explaining why his love life is a mess.

“I’m attracted to difficulty,” he jokes. “Great for a poem, not so great for relationships.” He sighs. “I am very proud of this book. I’m proud of making the duplex. But, you know, there are days when I ask myself, like, what the hell am I doing?”

Are you ever satisfied?

“No.”

Are you worried about that?

“A little.”

Brown pulls into his driveway, tilts his head toward his garden. He is pleased with his climbing roses, with how he took his plot of green and transformed it into a thing of kinetic beauty, a man with land who showed as much by giving it color. He is perturbed by the rabbits that plague his root systems, but only enough to write a poem about them (which is about rabbits the way Dancing with the Stars is about dancing).

Brown makes use of it all, his fury, his joy, his delight, his despair, the violence done to him, to everyone like him, roses, roots, rabbits. “Jericho writes the kind of poems you want to keep when there is nothing else left to keep,” Kaminsky observes.

“I’m trying something every day,” Brown says. “I don’t have the option not to wonder.” So it is for all outsiders who can’t stop observing, questioning, doing the math of injustice and cruelty. Brown carries the water of all that. Then offers the world a drink. “As a black queer poet from the South, I think my job is to add to the story, so more of its truth can be told,” he explains.

Brown says it was not so long ago he had to borrow money for gas to get to his graduate school classes. That he had to accept every free meal. He is grateful for the bounty that has sprung from what he’s planted. He has few illusions. But he has dreams.

“I’m interested in—what is that word? Posterity. I’m almost ashamed to say it, but when I die, I want to die in the South and I want people to think of me, if anybody ever thinks of me, to think of me in contrast to and in context of this place. That’s important to me.”

And until then?

“I just want to write a nice line and then the next.”