Travel

Lake House Reverie

Roy Blount Jr. steps back in time to his family’s old-school summers on the water

Photo: Michael Marsicano

In the middle of the night, my mother, Louise, woke up abruptly. Water was pouring onto her from above. She punched my father. He switched on the light, which was directly above my mother, took one look, and cried, “It’s raining in through the light fixture!” This happened one summer half a century ago, in what was then our homemade family cabin on Lake Burton, deep in the woods of the North Georgia mountains.

Closer inspection revealed rain leaking through a hole in the tin roof at another spot, creeping along the ceiling until it got to the light bulb, and then drizzling down. It was one of those things that happened at the lake. Once, our friend Mary Jo’s feet caught fire thanks to several jugs of water. Another time, my nephew Stuart woke up his parents to present himself coated with soot from head to toe (he’d been fiddling with a lantern in the night). Lake Burton was still semiwild back then, before weekend McMansions took over its shores.

My father, Roy Sr., wanted to grow up to be a home builder, but his carpenter father, having been deprived of all work by the Great Depression, talked him out of it. My father did eventually enable families to build or anyway to own houses, by becoming a prominent savings and loan executive, back when that meant something along the lines of James Stewart in It’s a Wonderful Life. And he did build that house on Lake Burton.

Photo: courtesy of the Blount family

The view of Lake Burton from the Blounts’ porch.

Burton is a beautiful lake, created in 1919 by the damming of the Tallulah River for electrical power. The water inundated the town of Burton, which had a post office, two churches, and a population of around two hundred, including the brothers Claud and Fred Derrick, who later played professional baseball. (At one point, Claud roomed with Babe Ruth.) Now more than fifteen hundred summer homes line the banks. I wonder whether any of the city people who take their leisure there ever heard of the Derricks, or have taken time to speculate, as we used to, about what a post office full of fish looks like. The last time I drove up there, our cabin had been torn down and replaced by a suburban-looking structure with a lawn of zoysia.

I was away at college and on summer newspaper jobs during the cabin’s construction phase, which must have been hair-raising. Daddy brought in the wooden prefab sections of the cabin’s frame by pickup truck over two and a half miles of old logging road that led from the nearest highway. Back then the road was unimproved, a lane and a half at best, clinging tenuously to the sides of old, rounded, but still steep mountains.

Photo: courtesy of the Blount family

Roy’s sister, Susan (second from left), and Chipper with friends.

“Three chickens,” a man up there once remarked to my father, “could eat all the gravel on that road in ten days’ time.” Along the seven hairpin curves and the intersection with a waterfall, the road had been widened scarcely enough to allow for all four wheels of a modern motor vehicle at once. A little rain—in a county with an annual rainfall among the highest in the nation—would turn this ribbon of red clay into a slalom course relieved only by stumps, bogs, fallen trees, and sometimes a car skidding toward you head-on. You might have to back up half a mile before you found a place where one car could get over by pulling up onto the mountainside or into a creek. Three cars rushing to escape as an incipient gully washer reduced the road to deep muck might encounter another line rushing in to pick up something from their cabins so they too could rush out.

But the road was diverting enough, back then, before you even got off onto the dirt part. Today I-85 goes most of the way from Atlanta to the lake, but in the early years we would travel the hundred-odd miles over streaked, pocked, hilly, aged, and simmering two-lane asphalt, with scrabbly shoulders of dry red dirt and dirty granite gravel, past squashed possums and dogs, bunches of leaning mailboxes, bony women rocking on porches, Womack’s Bait and Service Station, mules, tractors, dozens of metal church signs streaked with rust, a Cherokee burial mound, ubiquitous flaps of shed black tire rubber and fan belts, pieces of chrome, old men walking slowly up the road, crooked pine trees, busted watermelons, one of Georgia’s last surviving covered bridges, and a sign proclaiming Hoyt G. Head’s Deliverance Crusade. Pulling a boat and motor behind our station wagon, we’d go vwooop, vwooop, vwooop over the tortuous blacktop like a three-hundred-pound man who’s dreaming he’s a running back, turning end after end after end. Around Gainesville, the chicken capital of the world, we would start coming upon trucks carrying stacks and stacks of crates holding live fryers, and almost invariably one fryer would be out of her crate hanging on desperately in the back. We would honk and pass the truck, and my sister, Susan, and I would yell, “You got a chicken loose!” But the driver would never stop to check on one chicken.

From the beginning my mother pointed out that going to the lake was no rest for her. She could not refrain from cooking full-scale meals, or from rigorously cleaning up and making improvements under any roof of her own. Once, before we put in a stove, she cooked steaks on a barbecue grill outside in the rain, keeping them dry with an umbrella.

Photo: courtesy of the Blount family

Susan slaloming.

But she did enjoy looking out over the water at the mountains from our screened porch early in the morning, before the day’s outboards had churned up the lake’s surface, and hearing the lapping of the water at its edge. The sound that our dock made, pulling with the waves against the cables that moored it to two pine trees, reminded her of something comforting from her youth: the creak and slip, snap of a porch swing. “That’s something you might capture in your writing,” she said.

My mother also enjoyed picking blackberries and huckleberries (which our dog Chipper would eat off the bush), smelling the honeysuckle in season, and visiting a forsaken cemetery nearby with epitaphs like “We had him just a little while.”

Once my father, who never got all the way into the water himself, was dutifully pulling some young person on water skis when his favorite cap blew off and sank. Bright green, oddly elongated, and featuring a vintage likeness of Donald Duck, it was a startling topper on an otherwise statesmanlike-looking man, but nothing else kept the sun out of his eyes. I remember watching as he boated back after it a long ways, in the early evening, and my mother, snapping beans on the porch, saying, “Oh, he loved that cap.”

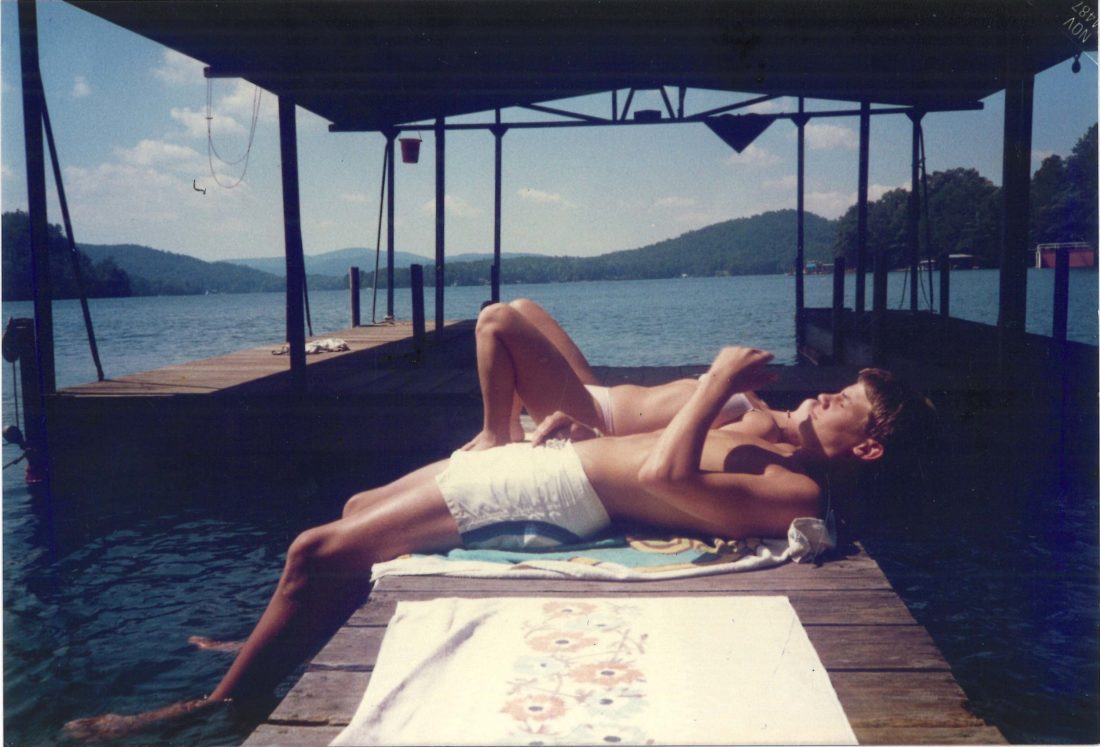

Photo: courtesy of the Blount family

Roy’s son, Kirven, sunbathing on Gracie, the canoe.

The Hickses and the Barneses, who went to our church, also built houses on the lake. Bill Hicks, Chet Barnes, and my father took pleasure in scrounging materials for each other (old telephone poles, oil drums, Styrofoam), insulting each other’s craftsmanship—“Well, I don’t believe I would have gone about it backwards like that, would you, Chet?”—and joshing about the keeping-up-with-the-Joneses aspect of the pioneer life: “I guess everybody’s going to have to break down and put in a commode now that Barnes has.”

But none of them were as pointed as Mr. Kastner, a wizened local man with a piercing indirect gaze who subsisted on truck farming, allegedly some distilling, and what carpentry he felt up to. One day, when he was helping Chet and my father with some project, he said, “When you goin’ to build a fence?” They assured him they weren’t ever. “We have a name,” he said, “for city folks that come up here and build fences.”

Photo: Michael Marsicano

One Saturday when Chet asked him if he could come back and work the next weekend, Mr. Kastner said, “No. I promised to help that other damn fool across the lake next week.” He conceded that my father could carpenter, but he told Chet, an insurance executive of some stature, that whoever had the idea that Chet could even take part in building a cabin “sent a boy to do a man’s work.”

The Kastners had sent all of their children to small Georgia colleges, and they had gone on to take good jobs in states as far away as California. When my father observed that it was sad to see the young folks leave home, Mr. Kastner said, “If mine didn’t leave when they got growed, I’d run ’em off. They wouldn’t be no good.” He wouldn’t join us at meals, saying, “I brought my dinner.” When we would stop by his house to negotiate payment, he would come out front and his wife would stay sitting inside out of sight. He’d say, “That’ll be $13.75 for the time and $4.25 for the paint and nails. Seventeen dollars.” She would call out, “Eighteen,” from the shadows. Once, we heard, Mrs. Kastner got dressed up and went with her ladies’ club on the bus to Atlanta, to shop for the day. She couldn’t settle on what to buy with the money she brought, so she came back home with it all. We thought that was touching. The Kastners may have thought we were touching.

The Barneses brought Aunt Josephine and Uncle Lewis, a sister and brother who lived together, to the lake sometimes. Aunt Josephine, elderly, was built like a manatee and hyperactive. One day, though it was her first time to watch anyone water-ski, she was on the dock telling Chet how to teach his daughter Judy how to ski and Judy how to learn.

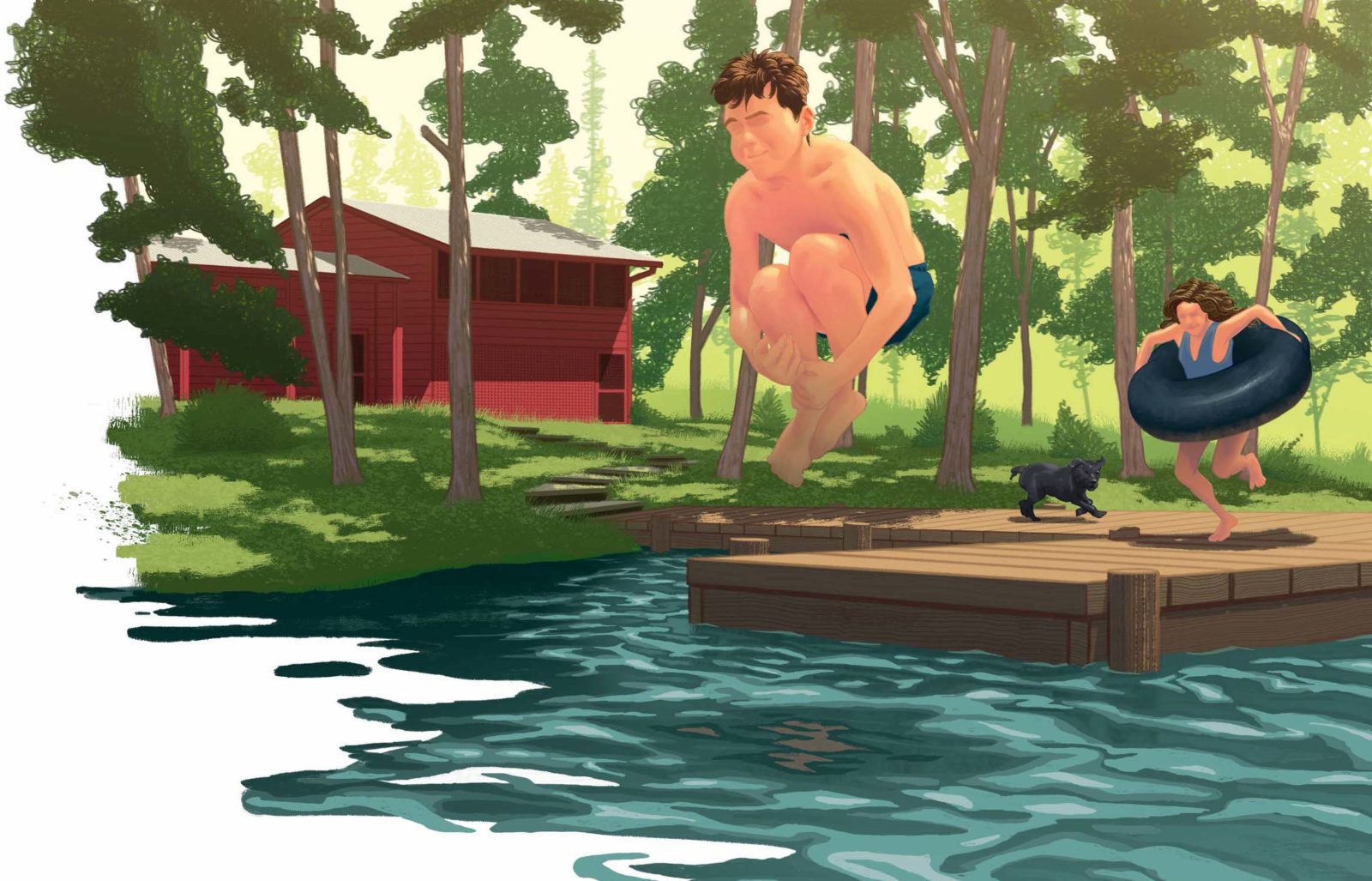

Roy’s daughter, Ennis, messing with Kirven on the dock

“J. C.!” she shouted across the water (that being the family name for Chet), “that child’s not ever going to learn how to ride that ski if you don’t drive that boat slower!” Mary Jo, Chet’s wife, said, “Aunt Josephine, he has to drive fast to pull her up.”

“Oh,” Aunt Josephine said. “Drive faster, J. C.! Faster!”

With that, and body English, she pitched forward off the dock and into the lake. Her flower-print dress billowed out around her like a parachute and she thrashed and hollered, “Help! Lord, get me. I can’t swim!”

Photo: courtesy of the Blount family

Splashing around.

My mother, who couldn’t swim either, plunged right in, heedless of her own safety, and found herself standing in fifteen inches of water, grasping at Aunt Josephine’s skirts and assuring her that she was coming.

“Aunt Josephine,” my mother said after a moment, “you’re sitting on the bottom.”

“Oh,” said Aunt Josephine, and after some heaving and straining by several people, she was up and wading around.

But most of our family’s lake adventures derived not from contrived aquatics but from fundamentalist logistics, transformed by nostalgia and the out-of-doors. At the lake we went back some ways toward the soil, some ways toward nature, but mostly back to old-fashioned, hardscrabble homemaking or home-building chores—a sort of ritual reenactment of the down-home hard times my parents and their friends knew, by experience and heritage, in their formative years. At the lake these chores could be recreative.

Uncle Lewis was older, smaller, and quieter than Aunt Josephine. He had vivid white hair and small bright eyes. My mother was painting the porch floor one night when Uncle Lewis came by with his ukulele. He played “Sweet Rosie O’Grady,” “Carolina Moon,” and “My Wild Irish Rose,” and sang them in a high cracked voice, while Mom stayed on her knees singing along politely and brushing on paint.

Photo: courtesy of the Blount family

Roy waving from the house, with Kirven and cousin Audrey below.

On the extremely hot day when Mary Jo Barnes caught fire, she and Chet had boated over to the place of a man they knew with a well. They had made arrangements to obtain drinking water from this well regularly, and after filling up a load of glass bottles, they headed back home with them in the bottom of the boat, around Mary Jo’s feet. When they reached their dock, she stood up and started handing the bottles out to Chet. She kept saying she smelled something burning, and he kept saying no she didn’t. But she insisted, and then she yelled, “It’s me!” The sun shining through the water jugs had set her tennis shoes on fire. She had to dunk each of her feet, in turn, over the side.

In 1959, when my father leased our plot from Georgia Power for fifty dollars a year, the woods were full of bears, foxes, and mountain goats. We could often watch a deer or an enormous snake swim from cove to cove as we ate breakfast on our screened porch. A toad would hop out from under the cabin’s front stoop whenever we arrived for the weekend. Or else Mother would say, “Well, I wonder where our old toad is?” By 1981, she and Daddy and Chipper were gone. Susan and I had moved up North. The lake house passed out of the family.

The other day I looked the property up on Google Earth. Where our cabin had been looks like a defense compound. Is that round thing a helipad? A covered swimming pool? At least a patio. A patio! Lots of podlike dark-green roofs. I’ll bet acorns don’t bounce off of those the way they did off our tin one. Good thing my kids and their cousins had a chance to be under that roof.

I guess we had a part in denaturing the area around the man-made lake. But our encroachments were modest. One fall afternoon, Susan and Mother and I drove up without Daddy for some reason. We towed the boat, which was packed with supplies including a whole ham, fresh out of the oven. On one of the single-lane switchback roads, we looked out the window and the boat was alongside of us. The trailer hitch had come off. We wrangled the trailer back and hooked it up temporarily. Found a gas station with a guy available for welding. But then, when we got to the boat ramp we used, something was wrong with our old fifteen-horse Johnson motor. I got it cranked, but it just barely put-putted.

Photo: courtesy of the Blount family

Kirven paddling the canoe.

We were miles from our cabin. It was turning cold. And more important, dark. But Susan is a born navigator.

“We turn at the school bus,” she said.

“School bus? What school bus?” I asked.

“There’s a school bus,” she said.

Very few lights lit the shore, and no moon to speak of either. We poked along on the lake for three spooky hours. Couldn’t even see each other, except fleetingly with our single, carefully conserved flashlight. I worried that Chipper, who was old by then and had no use at all for cold weather, would lose patience, but she was as oddly calm as the rest of us.

There was the school bus. Somebody had turned it into a cabin. Around midnight, we reached our dock. I remember that ride as one of our least stressful family times together. Chipper had kept warm, we discovered, by sleeping on the ham.

Photo: courtesy of the Blount family

The kids catching rays.

Another dark night, when most of the lakeside lots were still uncleared, Mother and Susan and I got lost on a walk. We came upon a house. We knew we didn’t know the people there, but the outlines looked familiar, so we crept up close in hopes of getting our bearings. Suddenly the residents switched on a row of preposterously brilliant outdoor lights and confronted us, stooped in surreptitious poses. We ran off into the woods, delighted, feeling almost like indigenous fauna.