Music

My Wild Ride with Jimmy Buffett

How a chance career opportunity turned into an enduring friendship that ended too soon

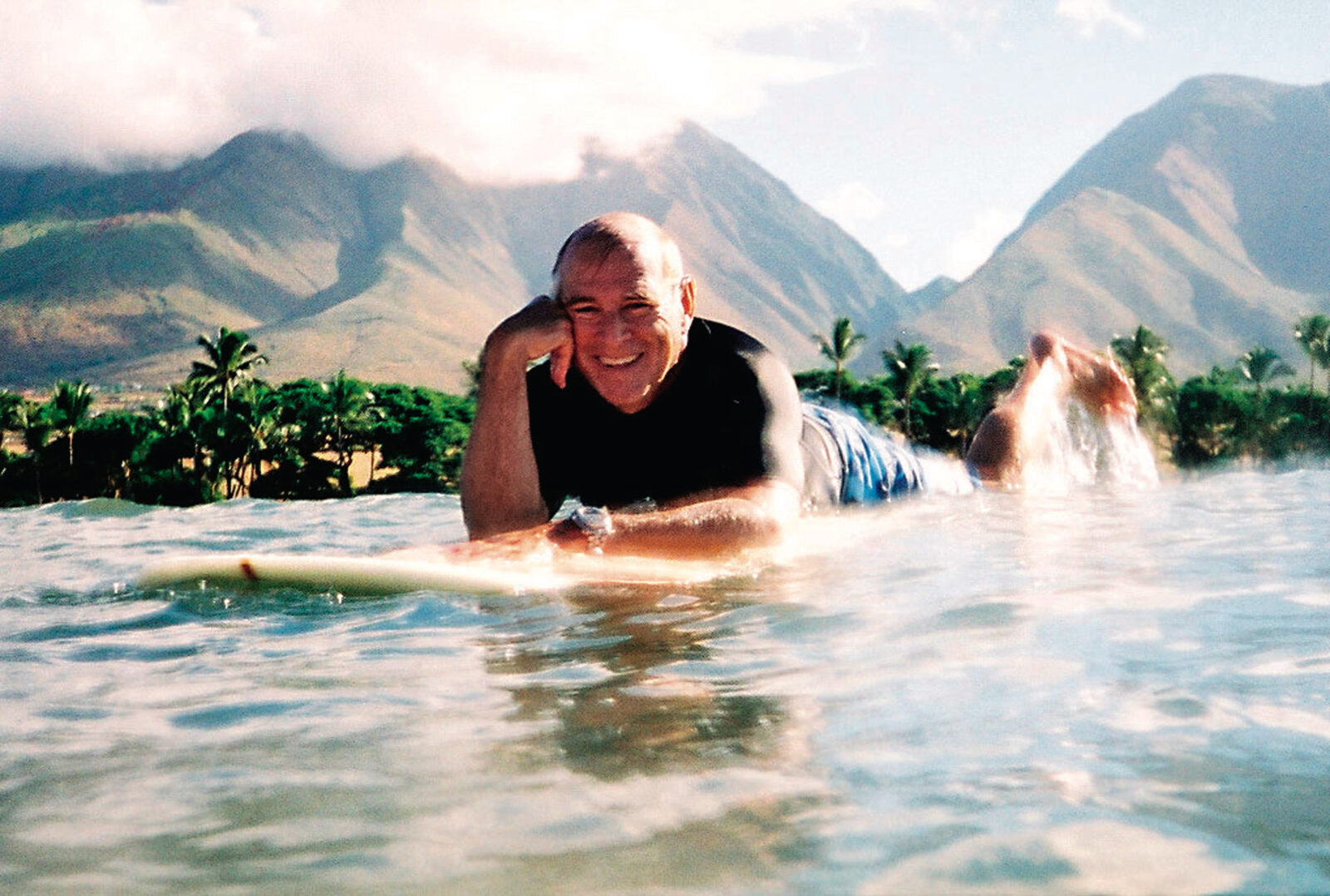

Photo: chris dixon

Jimmy Buffett in form in Maui in 2000.

One fine morning on Earth Day in 2022, my cell phone lit up with a Hawaiian phone number from a caller the device has long identified as “The Dude.”

“Hello, dude,” drawled a friendly, salty voice. “I’m heading out to Folly tomorrow. You have any time to catch up and go for a paddle?”

The caller was none other than Jimmy Buffett. And by God, when God’s own drunk and a fearless man calls you to go paddleboarding, you go paddleboarding. Jimmy was in Charleston, South Carolina, where I live, to rehearse his upcoming summer tour. Per custom, he was flying under the radar. Per custom, I was expected to both honor that and be ready for whatever adventure—or misadventure—lay just ahead.

I first met James William Buffett on a midsummer’s day in 1999, a few weeks after I’d walked into the Manhattan offices of Men’s Journal, clutching a notebook of slide photos and with a hopeful headful of article ideas. There, the legendary editor Terry McDonell introduced me to an energetic young staff. Circling back to his office, he then asked a question that would change my life: “Do you know Jimmy Buffett?”

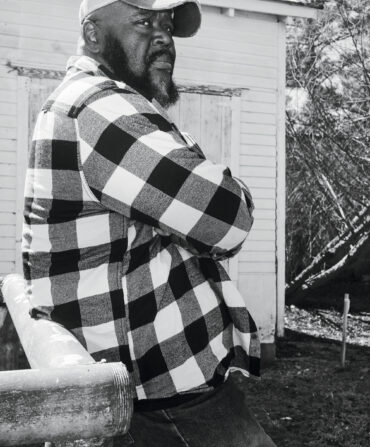

Photo: chris dixon

Buffett on Bull Island in South Carolina.

I might as well have been struck by lightning. No, I did not know Jimmy Buffett. But like most Southerners, I felt like I did. Growing up between Atlanta and the South Carolina Lowcountry, I internalized his music as if it were the soundtrack of my life. Seeing him grace a cover of Men’s Journal—casting a fly rod from the wingtip of the Grumman Albatross seaplane he called the Hemisphere Dancer—and reading the accompanying excerpt from his book A Pirate Looks at Fifty had actually helped cement my decision to head to New York. I left my job at Surfer magazine in Dana Point, California, and traveled three thousand miles in a wheezing VW camper. McDonell, who years later would pen a memoir called The Accidental Life, told me Jimmy was looking for a surfer who could code HTML, write, and sort of document his life and tour. “It’s not writing for the magazine,” McDonell said. “But it could be pretty interesting.”

A few weeks later, my VW puttered into a nondescript driveway in Sag Harbor, New York, where I was met by a fit, friendly guy sporting flip-flops, a pair of Quiksilver trunks, Ray-Ban aviators, and a navy hat bearing South Carolina’s palmetto-and-crescent emblem. “Hi,” he said, extending a hand. “I’m Jimmy.”

Photo: Christopher Lane

Buffett surfing in Montauk in 2008.

After a few minutes discussing our mutual South Carolina connections—Jimmy’s wife, Jane, was from Columbia, and he had in-laws in Georgetown, where my dad lived—I was sitting beside him in a small shed filled with photos, fishing rods, surfboards, and a fly-tying stand, editing home movies he’d shot with his young son, Cameron, on a tiny Bahamian island. Then and there began my own accidental journey. Jimmy decided to entrust me with a sort of proto-blog we would call Travels with a Pirate. I would click the shutter while flying aboard that old Albatross from Bimini clear out to San Diego. I would hit the record button as he cast for tarpon on Rum Cay or unspooled tales that left me slack-jawed—like the time he asked Joni Mitchell to sing “Carey” to a pal in St. Barts. “You gotta sing this for Groovy,” Jimmy remembered saying to her. “He came all the way across the ocean by himself.” So Mitchell sang it a cappella while Groovy wept.

Photo: chris dixon

In his element on Maui.

I surfed with Jimmy everywhere from Palm Beach to San Onofre to Lahaina. And I ended up with the truly baffling good fortune to come to call him, and the motley extended family that made up his band and crew, my friends. I would learn many truths about Jimmy Buffett, but here are three. First: He was just about exactly the person you hoped he’d be. Second: Beyond his well-documented lust for life, he was witty and kind. (You know how some folks say you should never meet your heroes? Well, Jimmy wasn’t my hero until after we met.) Third: Jimmy Buffett was an endlessly entertaining, truly fascinating, and occasionally terrifying person to try to keep up with. By the time I came on board, he had pretty much given up on the harder-partying aspects of his piratical life. What that meant in practical terms was that he channeled his boundless energy into seeking out adventures that regularly scared the crap out of his entourage, and sometimes me.

Photo: chris dixon

Buffett surfing at Waikiki, Hawaii, with Diamond Head in the background.

Photo: chris dixon

Buffett flying above Cape Hatteras in his Cessna Caravan.

I never had the chance to survive a ship-sinking offshore gale with him like his longtime friend and fellow Mobile Bay angler Jimbo Meador, or wakesurf amid the 1,400-horsepower prop wash of Jimmy’s massive old Albatross like his right-hand man Mike Ramos. But I did sit behind Jimmy as he banked that Albatross so hard above the blue Gulf Stream that I nearly passed out. I gaped as he piloted his Cessna Caravan seaplane down onto blue Bahamian water, and later between two crags onto the tiny runway of Gustaf III Airport in St. Barts. In 2008, I helped him very nearly drown his one-of-a-kind, veggie-oil-powered Sportsmobile camper—a vehicle I’d helped him build out—during a rising tide at Montauk Beach. A couple of years after that, I again death-gripped the armrests as he buzzed and banked, literally at dune level, around the Cape Hatteras lighthouse during a Wright Brothers pilgrimage.

Photo: chris dixon

Buffett (right) with Jimbo Meador (center) and Folly Beach shrimp boat captain Neil Cooksey.

But it was here in his beloved Lowcountry that Jimmy and I shared our most memorable adventures. Once on Bulls Island, north of Charleston, Jimmy thought it would be worthwhile to brave the wildlife refuge’s plentiful alligators to surf a nice right-hander running down the spooky boneyard beach. The waves were breaking among the dead trees of the island’s erosional maritime forest, but Jimmy deftly guided his nine-foot Stewart rounded pintail around the trunks and stumps, and we lived to tell the tale.

A couple of years later, over a bowl of cheese grits at Folly Beach’s Lost Dog Cafe, Jimmy asked me about a wave he’d scouted from his plane that broke maybe a mile offshore in front of the Morris Island Lighthouse. “It’s kind of sketchy,” I said. “Lots of big fish and currents. But it can get good.”

Photo: chris dixon

Dodging alligators on Bull Island, South Carolina.

“Well shit,” he said. “Let’s check it out.”

After stand-up paddling for twenty-five minutes, Jimmy, my local filmmaker buddy Scott Snider, and I began walking across the partially submerged sandbar that marked the edge of the surf zone. Scott and I were maybe ten yards ahead of Jimmy when we heard a bellow of pain. Terrified I was about to see bloodstained water, I turned to see that Jimmy had instead been lit up by our local species of box jellyfish. Scott and I were zapped moments later too, but not like Jimmy. Angry welts spread along his feet and lower legs, and I worried he might go into shock. Instead, he calmly looked out to sea and said, “We probably should paddle back in, but we came this far. I have to catch at least one wave.” And so he did.

After that, Jimmy’s running joke became “Well, Dixon, how are you going to try to kill me today?” My emphatic answer came in 2018 with Hurricane Florence. As Florence was churning toward the Carolinas, the day before Folly Beach was put under an evacuation order, I met Jimmy and his nephew Whit Slagsvol just south of the pier. The waves were nearly scraping the bottom of the decking and crashing down in the sort of slow-motion way that says, You’re going to get annihilated. A wicked nearshore current swept southward. “You sure you wanna paddle out?” Whit and I asked. Seeming more like a pirate looking at fifty than seventy-one, Jimmy grinned and said, “Shit yeah, let’s go.”

Photo: chris dixon

Buffett after getting stung by jellyfish off Morris Island.

Waves obliterated us on the way out, but each time, Jimmy properly turtle rolled beneath his board, then sputtered to the surface, bearing a look of sheer determination. Eventually we were far out, even with the end of the thousand-foot-long pier. The waves were moving so fast that Jimmy was struggling to gain paddle momentum on his relatively short, thin Stewart. I didn’t want to be the person responsible for drowning Jimmy Buffett, so I tentatively asked, “What do you think? It’s definitely getting bigger. Should we paddle in?”

Again, Jimmy just smiled. Paddling in through that maelstrom would be no picnic either. “Nope,” he answered with a Zen calm. “I wanna catch a wave.”

Whit caught a long left-hander all the way in. Then the next wave of the set reared up. Jimmy hollered: “Go, Dixon!” I hesitated. If you go, you’re gonna leave him out here all alone. But Jimmy yelled again, “Get it, dude!” And so I did.

Jimmy looked like a speck against the dark ocean as Whit and I turned to paddle back out. A huge set of waves obscured the horizon way outside. Jimmy paddled over a first wave taller than his nine-foot board, then over a second. I’ll never forget watching him swing his board around to paddle for the third. He windmilled his arms, and as the swell lifted him, he stood and assumed a textbook-deep crouch. The wave reeled southward and he rocketed along, just ahead of the erupting whitewater. He finally leaped off in thigh-deep water after a ride probably two hundred yards long and surfaced with a whoop. I hadn’t killed him.

Back on the beach, I snapped a picture of Whit and Jimmy clutching their boards. Jimmy posted it to his Instagram page with a nod to the lyrics to his song “Surfing in a Hurricane.”

I ain’t afraid of dying

I got no need to explain

I feel like going surfing in a hurricane

#follybeachsurfing

The post got picked up by CBS News, Fox News, USA Today, and even the Washington Post. Some folks said Jimmy was being irresponsible. But we weren’t under an evacuation order, and there were waves to be surfed. Still, Jimmy went on to add a line to the post: “On a serious note—respect mother nature, please be safe and listen to your local authorities.”

By the time Jimmy rolled up to my house near Folly Beach on that Earth Day morning, I had already recruited Scott Snider and fellow surfer and lensman Luke Pope-Corbett, on Jimmy’s hopes that we might nail some aquatic footage for him to use on the big screen during the summer leg of his Life on the Flip Side tour.

I was aware Jimmy had been under the weather, but aside from looking a bit thin, he was as energetic as ever. We stroked out of the small tidal creek and cruised toward an uninhabited island near my house in search of tailing redfish and bottlenose dolphins. Out on Folly Creek, we intercepted a full bottlenose family frolicking along a shoal of oyster beds and spartina grass. The mama and her babies made lazy circles around us—close enough we could whisper to them—and then moved off. Nearing the forested island, Jimmy pointed to a break in the trees. “What’s over there?” he asked. “There’s gotta be redfish in those shallows.” I’d honestly never even noticed it, but Jimmy somehow found a break in the marsh that led through a maze-like creek to where the trees parted. Sure enough, redfish were popping through the shallows. We heard the screech of a bald eagle and the knock-knock-knock of a big woodpecker. Soon, that mini maze opened up to a tiny sand beach that curved around into a stunning tidal creek bisecting the island. Pushed along by the rising tide, we paddled through a cathedral of trees until the creek simply petered out. Luke and Scott nailed the footage, but Jimmy was too mesmerized to notice. “Jesus, dude,” he said, pulling up onto the sandbar. “This place is beautiful.”

The next day, he rolled up around daybreak so we could get in a paddle before his noon flight back to Sag Harbor. The tide was quite high, so we reckoned we’d cruise across a different flat in the direction of Morris Island. But as we left our little creek, a pair of dolphins surfaced, so we followed them at a distance. We tracked them silently, just watching and listening as they breathed in and out.

Our dolphins here exhibit a fascinating behavior. When tides permit, they swim into the mudflats and shovel their beaks through the pluff mud in search of blue crabs. Sometimes they really get into it, churning the waters violently with their flukes. On very rare occasions they’ll headstand, pushing three-fourths of their bodies straight out of the water. Jimmy was within twenty yards of the big male when he started arching his back and hurling mud. I turned my camera from the female just as the male went vertical, flopping his body back and forth for a few seconds to get down deep and waving his tail at Jimmy in what was probably the most impressive headstand I’ve ever seen. Momentarily transfixed, Jimmy bellowed a deep, satisfied laugh. “Man, I’ve seen dolphins do a lot of things, but I’ve never seen that.”

The next day, he rolled up around daybreak so we could get in a paddle before his noon flight back to Sag Harbor. The tide was quite high, so we reckoned we’d cruise across a different flat in the direction of Morris Island. But as we left our little creek, a pair of dolphins surfaced, so we followed them at a distance. We tracked them silently, just watching and listening as they breathed in and out.

Our dolphins here exhibit a fascinating behavior. When tides permit, they swim into the mudflats and shovel their beaks through the pluff mud in search of blue crabs. Sometimes they really get into it, churning the waters violently with their flukes. On very rare occasions they’ll headstand, pushing three-fourths of their bodies straight out of the water. Jimmy was within twenty yards of the big male when he started arching his back and hurling mud. I turned my camera from the female just as the male went vertical, flopping his body back and forth for a few seconds to get down deep and waving his tail at Jimmy in what was probably the most impressive headstand I’ve ever seen. Momentarily transfixed, Jimmy bellowed a deep, satisfied laugh. “Man, I’ve seen dolphins do a lot of things, but I’ve never seen that.”

Paddling back to the house, Jimmy asked me, as he always did, how life was going. How was Quinn’s teaching job? How were Fritz and Lucy? “Damn, she’s gonna be a senior in high school? Man, my kids grew up so fast too.” He told me never to miss an opportunity to share an experience with them before they’re out of the house—“because that’s what you’re gonna remember.”

I didn’t want to dwell on Jimmy’s health, but I was, of course, concerned. “It’s been a rough go, honestly,” he said. “But things are looking up. I think I’m actually gonna be able to go on tour. It’s really true, you know. Getting old ain’t for the faint of heart.”

Four years prior, Jimmy had helped me brainstorm—and find my direction on—a book called The Ocean: The Ultimate Handbook of Nautical Knowledge. Writing it had kicked my ass. “That book wouldn’t have happened without you,” I told him. “My career. My life, really. I owe a lot of the good things that have happened to me to you. I’m very lucky, and I just want to thank you for that.”

“I’m proud of you, dude,” he said. “But it’s not luck. Or not entirely. We make our luck.” He swept his arms around and gestured to the sky. “And look where we are right now. Look what we just experienced in your backyard. We don’t have to go to church. It’s right here.”

That was our last time on the water together.

Photo: Quinn Dixon

From left: Luke Pope, Scott Snider, Luna the Lab, Buffett, the author, and Pippa the mutt in 2022.

Photo: chris dixon

The author and Buffett digging out the Sportsmobile in Montauk.

As I type these final words, the tears are starting to well and the grief is, again, washing over me like a wave, so maybe it’s time to close the computer and get out on the water. I’ll leave you all with a few parting thoughts.

First, until the day I die, I will never cease to be inspired by Jimmy Buffett. He never stopped taking risks and pushing himself—even when he was battling cancer, and even when it drove those who cared about him crazy. Doing so would have been antithetical to the Fearless Man he truly was.

While I’ve watched that fearless man move very fast, I’ve also watched him slow down enough to spend hours on a front-porch rocking chair, recording personalized greetings and messages of hope for terminally ill fans. It’s not something he ever told folks about, but he did it just the same. I’ve seen his Singing for Change foundation fund projects at hundreds of nonprofits. And I’ve marveled as a collection of personal surfboards he donated allowed the founder of Folly Beach’s Warrior Surf Foundation to quit his day job and focus on the veterans’ organization full-time.

Photo: chris dixon

Buffett and the author’s daughter, Lucy.

Photo: chris dixon

The author, his daughter, Lucy, and wife, Quinn, with Buffett in Sag Harbor.

I’m not Bono, Alan Jackson, Tom McGuane, Joni Mitchell, Bill Clinton, Kenny Chesney, Sir Paul McCartney, or any of the litany of famous folks Jimmy called his friends. I’ve always just sort of been one of the “gypsies in the palace,” as is the case with most of the people who worked behind the scenes for Jimmy—people he truly loved and treated like family. My stories, while unique to me, aren’t unique. If you had the chance to bask in Jimmy’s glow, whether through a chance encounter at a fishing dock, a wedding photo he crashed at a Margaritaville restaurant, a wave you shared at Ditch Plains, a beer you sipped at a Key West dive, or a massive concert filled with screaming Parrot Heads, you were a fortunate person indeed. And you knew, because it was obvious: Jimmy Buffett cared about you.

On the Saturday morning after Jimmy’s death, my wife, my son, and I went out to a local landmark—an old boat deposited on the side of Folly Road during Hurricane Hugo that has since become a canvas for folks to paint odes to friends and family. Marriage, graduation, retirement, birth, death—we read about them all on the boat. With a gallon of latex and several spray cans, we painted a wave, a palm tree, and a simple message on the old hull: Live Like Jimmy.

Fair winds and following seas, Mr. Buffett. I will miss you very, very much.

Photo: Quinn Dixon

Buffett and the author checking the waves at Montauk.