SEVERE WEATHER

Pulled from the Flood

After devastating waters wrecked a novelist’s Eastern Kentucky homeland last week, he worked alongside the helpers—those who refuse to let the voices of Appalachia go under

Photo: Will Anderson; Silas House

A room in the flooded Hindman Settlement School in Kentucky; the author, Silas House, found an old photo of himself among the waterlogged archives.

For long stretches we drive through people’s belongings on either side of us. We have to creep along because the debris is close. To navigate our way through we are required to see. I glimpse a blue and red plastic child’s bed that is shaped like a race car, a water heater, a box of Little Debbie Nutty Buddy bars, a baby’s nightgown, one shiny red high heel. A couch stands on its end. A large portrait shows a woman with two children smiling in matching white sweaters behind a shattered pane of glass. In the trees hang strips of unidentifiable plastic, tufts of pink fiberglass, jagged yellow sheets of plywood.

The flood hit Eastern Kentucky three days before, on July 29, and this section of Highway 15 between Jackson and Hazard only recently became passable. The creek has receded, but it still runs with a muddy, ferocious determination, slithering around a car lodged upside down between two boulders, a large toolshed that has somehow remained intact, a French door, a mess of broken furniture. Washed onto the higher bank, a mobile home bends like a loaf of bread that has been mashed in the middle. Then, a brick house with half its bricks fallen away. Another small house has been washed ten yards away from its foundation. All of the windows have been busted out, either by trees, detritus, or the weight of the rushing water.

A line of soldiers outfitted in grayish camo march down the road in single file. A woman in an orange vest directs traffic around a pile of broken lumber and twisted metal that hasn’t been moved out of the road yet. On a side road one bridge is completely washed away. On another bridge an entire house lies on its side, its floor-beams exposed.

Photo: Josh Mullins

Floodwaters around Hindman Settlement School.

Trees are uprooted and leaning all along the sides of the road, their bark stripped away to reveal startling whites and yellows. Telephone poles point in forty-five-degree angles. Waterfalls rush out of the mountainsides and in some stretches our road has partly collapsed so it is reduced to one lane.

Now we come to a wide, level section that I realize has recently been made that way; the emboldened creek has acted like a bulldozer cutting a swath through here, leaving in its wake more personal items. People move cautiously through the debris, bent over as if looking for Easter eggs. But instead they’re searching for moments from their lives. They are hollow-eyed, covered in mud, exhausted. A woman bends and plucks a swollen photo album from the saturated ground. She holds the book by one corner and water pours out of its pages.

We are headed to the Hindman Settlement School, where both my husband, Jason Kyle Howard, and I often teach in the Appalachian Writers’ Workshop, and where we first got to know each other. The school has been serving Appalachia for 120 years now, first as a boarding school that brought a classical education to an under-served population and now as a center for literacy, foodways, the literary arts, and more. The workshop, which has been a foundational literary gathering in the region since 1977, was in its fourth night when the historic flooding hit in the early morning hours of July 29. Some of its participants barely escaped before the flash flood got up to four feet deep inside their rooms. Others fled their apartments that are built into the side of the mountain, hanging over Troublesome Creek, because there were fears of mudslides. They all gathered in one cottage, spilling out onto its porch, and watched the water rise. By morning they’d find that the offices, many of the classrooms, other buildings, and lots of the campus grounds had been devastated. Many of their cars were carried away.

Photo: Will Anderson

An interior image after the waters began to recede.

Jason and I are driving to the Settlement School in hopes of helping. There are donation centers and clean-up crews set up in many places along our journey but we are aiming for Hindman not only because it has been the hardest hit—seventeen of the dead so far are from around the town, including four siblings aged one to eight—but also because the school and the community are heartstrings of ours.

Once we arrive, we find the Settlement is a beehive. Volunteers unload cases of water from an eighteen-wheeler. A woman scrubs at a row of Blackstone grills where meals have just been prepared. A father and his two daughters carry plates of food up to the cottage where several families who lost their homes are now staying. The porch there is crowded with people watching dogs and children play together on the yard. All of them are strangely quiet, even the children who are swinging with their legs arching high in the air. The shock is mostly present in their eyes and in how they move, stiff and somehow ghost-like. Other folks are unburdening their cars of diapers, detergent, paper towels, and canned goods they’ve brought to share.

The staff members of the settlement school, many of whom have suffered tremendous loss themselves, take action. The executive director, Will Anderson, helps unload the hundreds of cases of bottled water while overseeing the school’s massive operation. The night of the flood, programming director Josh Mullins was in the offices trying to save what he could when the floodwaters tore off the heavy doors and rose above his waist before he escaped, copiers and desks and everything else churning around him. Today he is out on a run for more supplies. Rita Ritchie, the office manager, and Teresa Ramey, the bookkeeper, are working on the payroll; staff will likely need their paychecks now more than ever. Many others are at work all over campus.

Photo: Timothy D. Easley / Associated Press

Hindman executive director Will Anderson in the wreckage.

The first person we see is Sarah Kate Morgan, the director of traditional arts. She is a phenomenal musician and a force who is always in motion. She is unloading buckets that she is going to fill with water to flush the toilets of people who are staying on campus since there is no functioning water at this time. A day later the maintenance foreman, Moses Owens, will figure out that a century-old cistern still works, providing the only running water for miles around. Sarah Kate often peppers her conversation with affable curse words, all the while wearing a genuine smile. When I tell her we are here to help she immediately fires off a list of things to do: We can unload or organize supplies, pull damaged furniture out of the ruined offices, help save the archives, and help prepare or serve food to the community. Despite its own myriad problems caused by the flood, the Settlement School has decided to open its doors and serve the region just as it always has. About forty people and twelve dogs are being housed there. The school is feeding and offering supplies to anyone who comes there seeking help.

Usually disasters around here are ignored by the media, or mentioned and lost in the next news cycle, but this flood has gained international attention. Two camera crews are present as soon as we arrive in Hindman. While they are mostly focused at this point on the destruction, the help being provided at the Settlement School is indicative of the general attitude of people in the region. Nobody is waiting for anyone else to come do the work. The people have armed themselves with rakes, hoes, and shovels. They’re moving debris and directing traffic alongside officials. Pentecostal church groups and organizations like Queer Kentucky are working together to organize collection centers and deliver supplies. A group of Mennonites from the area are set up on the side of the highway, dishing out fried chicken and mashed potatoes. Kristin Smith and Melissa Bond, married farmers who run the Wrigley Tap Room and Eatery in nearby Corbin, moved their services into the heart of the disaster area to cook for those in need. Groups such as E KY Mutual Aid, Appalachians for Appalachia, Foundation for Appalachian Kentucky, Appalshop, Pikeville Pride, and many others are on the front lines to help their own.

Photo: Mandi Fugate Sheffel; Silas House

Saving treasures in the Hindman Settlement School archives.

Melissa Helton manages community programs for the Settlement. She is calm, decisive, and while focused on helping those most in need, she is also clear that one of the most pressing concerns is saving what can be salvaged of the school’s archives. Most of them are wet and covered in the mud that has invaded everything. I am reminded of the woman pulling her family photo album from the muck. I am reminded of how my own mother grabbed only our photo albums and me when a flash flood took everything our young family owned decades ago.

Jason and I go to work after a quick tutorial by Melissa, who has been taught a few tricks by trained archivists who have volunteered their time over the last couple of days. Many of the items are beyond saving. Some of the photographs can be dried easily. Others must be dunked in water to remove the coating of mud, lightly dabbed, and hung or laid to dry.

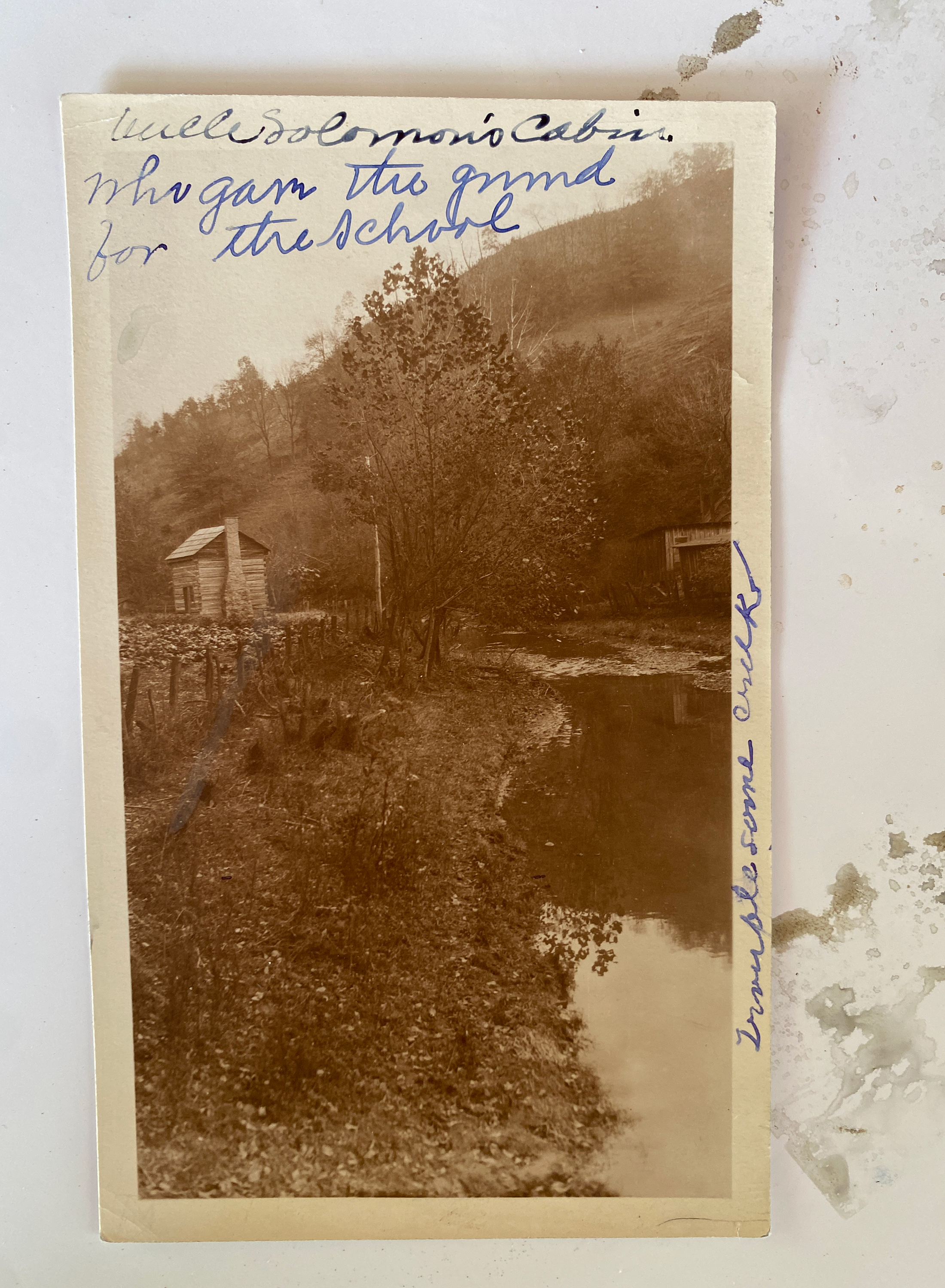

Photo: Silas House

A found photo of Troublesome Creek.

The archives hold not only the history of the settlement school but also that of the region itself. This loss is particularly devastating in part because Appalshop, a media, arts, and education center in nearby Whitesburg, was badly hit as well and houses even more archives of the region. At Hindman there are thousands of items detailing the daily lives of Appalachian people over the last century, showing everything from folks enjoying an early 1900s hike outfitted in suits or full skirts to children learning in computer labs just last year. There are recordings of legends like Jean Ritchie performing on stage and 1960s children participating in a maypole. I found a whole cache of postcards that had been sent to the school’s staff from James Still (author of one of Appalachian literature’s foundational texts, River of Earth) during his travels across Central and South America.

There were hundreds of pages of letters written by locals and the school teachers who came to the mountains from all over the country to participate in a social educational experience that changed the region for the better, old brochures from the writers’ workshop with a photo of beloved writer Lee Smith on the cover. Smith has been a longtime supporter of Hindman Settlement School and is the person who first sent me there. Dolls survived that had been handmade by Verna Mae Slone, a local woman whose 1979 memoir What My Heart Wants to Tell became a surprise bestseller. I even found pictures of myself during my long association with the school, including my first author photo, taken on the creek’s banks twenty-two years ago.

Photo: Silas House

Will Anderson, right, and Melissa Helton, foreground, help unload water.

The lives are the most important and disturbing losses, of course. The day we were in Hindman another body was found not far downstream from us. As of this writing, thirty-seven people are dead from the flooding, and Governor Andy Beshear says we should expect that death toll to rise. To be in Eastern Kentucky right now is to shed tears of sorrow, pride, anger, and hope, sometimes simultaneously. So many are in the depths of the worst kinds of grief. You can feel it when you’re driving those winding mountain roads, when you see people living in tents or shelters, when you see children trying to play when they know their family has lost everything they own. Seeing them, I can’t help but blame the coal companies who disrupted so much natural drainage, caused widespread erosion, and did more damage to the area that directly contributes to these disasters. I can’t help but blame the legislators who refuse to pass climate initiatives.

Today a heat wave has moved into the region again. The sun is beating down on the backs of people working hard to save what they can, to recover bodies, to clean out the seemingly infinite mud and muck. But the sun is also helping to dry up the saturated ground as well. The sun, though hot, is still shining for those left behind. And the people keep working.

To find more information and donate to the Hindman Settlement School, click here.

Photo: Silas House

Silas House, the author, hangs photos to dry.