Sporting

Quiet in the Woods

A hunter’s lessons in the deep magic of stillness

Illustration: Dawn Yang

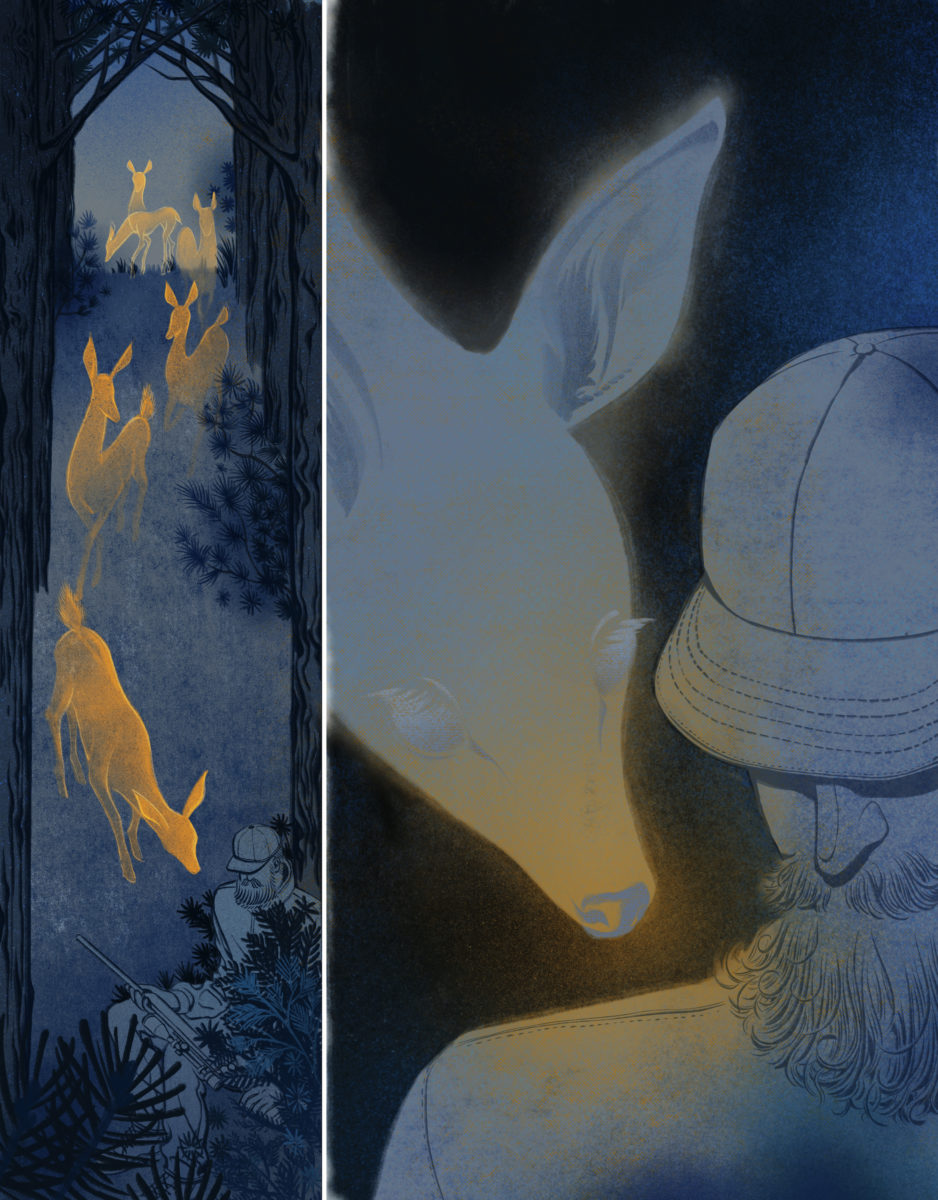

He tells me to go to where the trail forks, to set up there in the corner. From that spot, he says, I will be able to see down both lanes: the right running to an old food plot, the left dead-ending in bedding. The deer, he says, are likely to come from anywhere.

So midafternoon I slip in a good two hours before the evening movement. I find the place he’s described and tuck in to a thicket of stickseed and green briar where I’ll be concealed in a chair on the ground. I can see down the right lane to where the trail swells into a fallow opening. But down the left side, I can see only thirty yards to a bend, and past that is where I convince myself the deer will be.

The problem is, I don’t know the first thing about white-tailed deer. I’ve never killed one. I’ve never seen one in the woods while hunting them. I’ve come from small-game stock, from houndmen with kennels of rabbit-crazed beagles, old men who kept squirrel dogs and Savage 24s. For the most part, I was raised by fishermen. No one hunted deer except a great-uncle who lived on the opposite end of the state.

But the man who sent me to this corner, he knows deer and knows this place, which is to say, of course, I should listen. Instead, I pick up my chair and creep down to the bend. I fold into a stubby cedar tree that brushes me in against a pine. Now I can see to the end of the lane. About an hour before sundown, footsteps come heavy behind me. The sound is a good ways back, so I glance over my shoulder and see her. She is a young doe, probably eighty pounds, her coat slick and as tan as an acorn. Head down, she nibbles the grass, then looks up with ears alert. She glances back to where she’s come from, takes a few steps, and continues to feed.

Illustration: Dawn Yang

I make up my mind that I will not move until she passes me. The footsteps grow louder and I hold still, my eyes nearly closed, my heartbeat drumming. In the final moment, I realize I am sitting directly on a trail. Her head comes over my right shoulder close enough that I could touch her. I slightly turn just as she comes into my peripheral vision, and that sudden movement stretches her eyes wide. The doe all but comes out of her skin, just an explosion of muscle thundering over the ground and gone.

This is the first deer I ever hunt, and I do not kill her. Instead, I tremble in astonishment and wonder as she vanishes. I realize right then that if a man sits still enough, he might completely disappear.

* * *

The problem with dying is that there’s no good time to do it. When the turkeys stop gobbling, the flatheads start to bite. The catfish turn off just as the doves begin to dive into fields of corn stubble. The doves disappear and the whitetail rut kicks off. Season renders us to season, and we run ourselves ragged in pursuit of the game we chase.

I half joke that it’ll be a heart attack that takes me out of this place. They’ll find me at the base of a tree with muddy gobbler tracks stamped over my body, or sprawled on a dock having been shocked awake by a bait clicker, the slow tick-tick-ticking of a flathead taking line till the spool is empty and the rod itself slides off the dock into oblivion. Everyone who knows me knows how much I love the outdoors. They ask me to join them on hikes, and sometimes I go. The thing is, though, they walk too fast, at least for me. They tend to talk too much. When I’m with them, I keep pace and conversation because I know that’s what’s expected, but I’m bothered by the way the woods go dead around us. We are a fire glowing against a space that will not have us. Nothing dare step into that light.

As we stumble along, the deer hide and wait, squirrels melt into the limbs on which they hold, and birds cease their song. What we’ve come to be a part of wants no part of us. Deep down, I want to tell the person I’m with to sit and be still, that we must be quiet and treat this place like church. I want to tell them that if we don’t, we will surely miss the sermon. But instead I keep those things to myself for fear of ruining their good time, and in turn we see nothing. The more time passes, the more I tend to go to the woods alone.

* * *

In the dog days, the daytime heat always pushes me deeper into the night. Midnight finds me alone on the water, the North Carolina mountains resting black against the sky. I sweep the beam of a spotlight across the bank and scan for eyes that will glint like copper coins. When the brightness finds them, the bullfrogs slip into a trance that will not break so long as the light is steady. They cling to driftwood shadows until I’m close enough to gig them in the cattails and reeds.

While the boat passes between shores, I shine my light into the water and spot sunfish bedded in craters of swept-out sand. The fish tilt back and forth as if sleeping with fins waving soft as lullabies. A loud crack breaks the silence, and without turning the light, I know that a beaver has slapped its tail in warning. Above, blue-green nebulae hold like smoke amid the spangle, and I am dumbstruck that I’ve missed this till now. Who could care anymore what brought them here? I turn off the light and lie across the seat of the jon boat in wonder.

Come fall, when the leaves peak and the trees cast their color onto ripples of creek like oil fire, I watch a brook trout rise in an eddy where a stone’s back breaks the current. A bow and arrow cast sets a Cahill to air, and as the fly lands, I wrist flick mends of line to keep it there. The trout comes up through a glitter of mica, rolls across the fly, and dives back toward a cobblestoned bottom. I set the hook and feel weight.

After a few strips, the fish flaps in the shallows by my boots. I kneel down and wet my hand, scoop this marvelous thing onto my fingers. Autumn is reflected down the flanks, colors blending like that of a sugar maple: green to goldenrod, tangerine to scarlet. The dark green back is swirled with lime marmorations and red spots haloed in pale blue coronas. There is a sunset painted across my palm.

Winter renders the landscape to pen and ink, and I am in a tree waiting for a deer that will not show. A charm of golden finches fly over the wood line and land in the brush and scrub pine at the far edge of a clear-cut. Slowly the birds make their way toward me, landing in places that suit them for reasons I cannot know.

I am bundled and cold, and that makes it easy to hold still. The tree stand is in a hickory backdropped tightly by dogwood. In a moment the entire charm converge on that singular point. They clasp to limbs like leaves and are so close to me that when I focus on a single bird, I can see barbule and barb of feather, strands as fine as baby’s hair. My vision pulls back, and I am surrounded by yellow that is too bright to fathom. The universe becomes a single color, and I am ensnared within it.

* * *

All that I know of beauty, I learned through rod or rifle. For me, fishing and hunting have been the mechanisms that placed me squarely into the heart of things. I don’t intend to suggest that this is the only means, just that without some project few would climb twenty feet up a pine two hours before daylight. People chase vistas to catch sunrises. They round bends in trails and stumble onto black bears, surely a stroke of luck. But who else shivers cold in the dark up a tree that is miles from any road or trailhead and is waiting when the blue fog melts off the saddle at first light? Photographers? Madmen? Maybe. And if so, I will gladly share the woods with them.

What I’ve come to love most about those mornings is the flip of the switch when the world cuts on. You slip into a place at full dark and wait out the silence. You’re there when the first bird calls and the second answers, when life suddenly blooms out of every space that offered the slightest shelter from night. The only requirement is that you hold still unflinching and dare not break the spell. As Wendell Berry wrote, “For a time [you] rest in the grace of the world, and [are] free.”

* * *

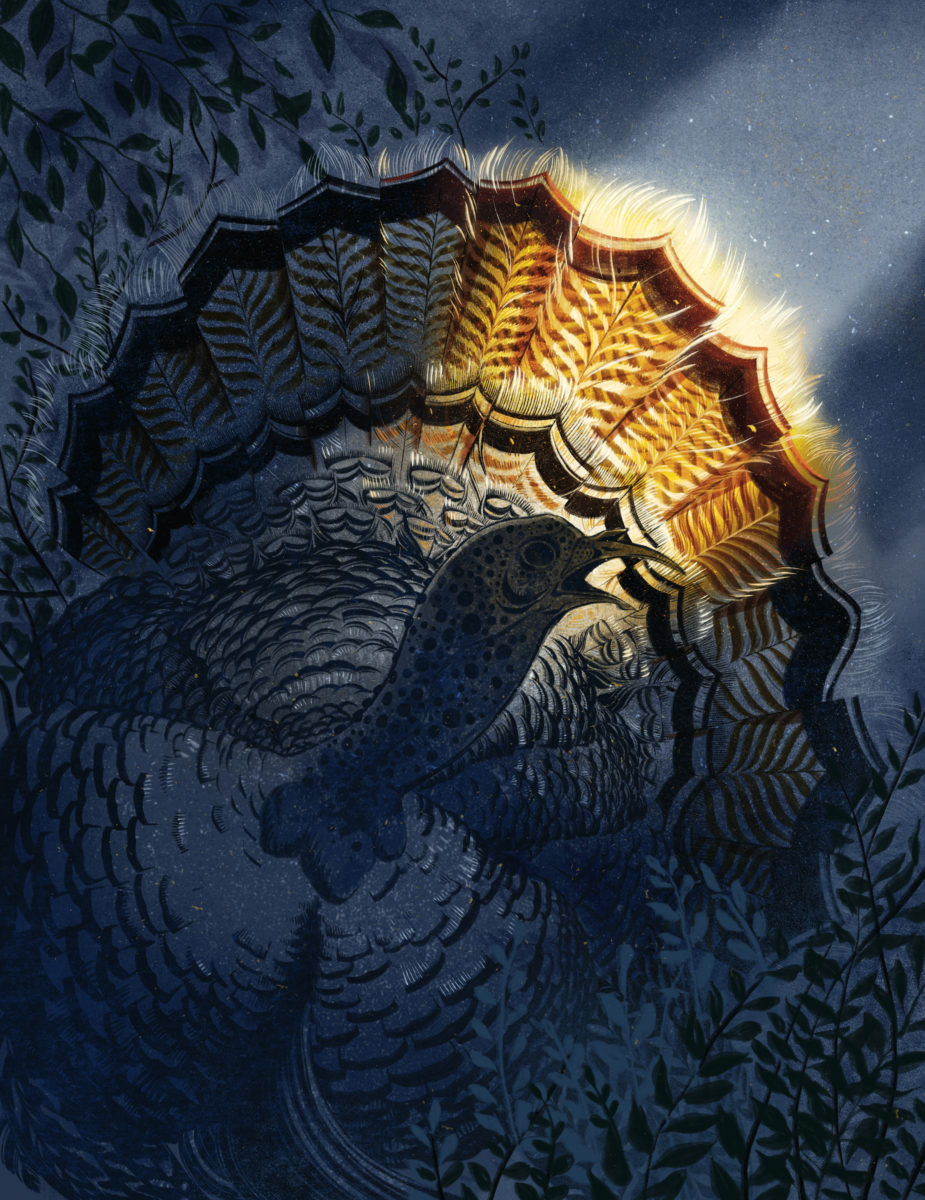

The pinewoods have been opened by fire, and spring has started to push its green face out of the ash and black. By summer what’s been burned empty will fill again, but for now there is no cover and no place to hide, so I crawl down a dry creek bed, praying the turkey won’t see my approach.

The morning has just brightened from black to sapphire, and the bird hammers again from his limb, a sound so loud and close that it crashes against me like thunder. I peer over the lip of the bank for somewhere to sneak within range, and I see an old pine nearly three feet through that is more than enough to conceal me. I lean against the tree, my torso now trunk, my legs spread over scorched ground like exposed roots. Somehow I’ve managed to make it within fifty yards of where the gobbler is roosted.

Illustration: DAWN YANG

The woods are waking up around me, and I have to fight off the urge to rush things. I wait a few minutes for the light to get up before I call, and when I do it is nothing loud or startling, just a subtle tree yelp sent from the bell of a trumpet. I am not expecting the response. There is no beat of wing or fly down, just gravity and ground, the dull thud of the bird hitting earth as he drops off the limb like a stone. He stands in the clearing and cranes his neck to study the layered shadows where the call has come from, but I am cupped in a dark hollow that light has yet to find, and no matter how hard he tries, he cannot see me. For the turkey, survival requires absolute certainty, and so the wood line becomes his line in sand. He will not come any closer.

A dogwood winter sets his breath to air, every gobble a sound written out like a score of smoke that hangs before him till the echo fades. He swells into strut and rakes his wing tips through the frosted grass, his head drained white as ice. For a long time, this is all that exists between us. I am a tree, and he is a dancer. The sun takes an hour to crest the pines, to warm that glacial blue dawn, and in that time he walks like eyes across a page, without one step taken into the margins.

When the first rays break the treetops, I watch his feathers turn to stained glass, a fan backlit bronze and barred, the outer curve fringed in gold. I cannot move, and I do not want to. Here is where I would spend my forever, heaven and earth the very same place, though even while I breathe it, I know that it cannot last. As quickly as it has come, it will go. There is always the flip of the switch. The world is awash with miracles, and I am thankful to simply bear witness.

David Joy, a twelfth generation North Carolinian, is the author of five novels, most recently Those We Thought We Knew (winner of the 2023 Willie Morris Award and the 2023 Thomas Wolfe Prize). Others are When These Mountains Burn, The Line That Held Us, The Weight of This World, and Where All Light Tends to Go. He is also the author of the memoir Growing Gills: A Fly Fisherman’s Journey and a coeditor of Gather at the River: Twenty-Five Authors on Fishing, a book that raises money for the CAST For Kids Foundation. Joy lives in Tuckasegee, North Carolina, with his dog, Edie Munster. Read more at his website.