Arts & Culture

Southern Masters: James Lee Burke

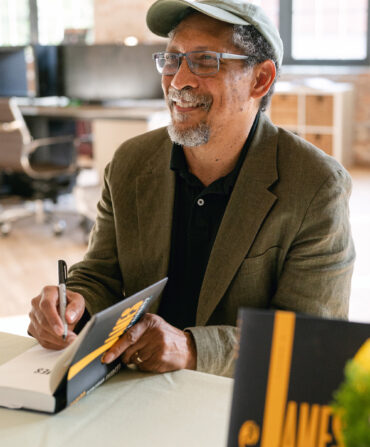

With thirty-five novels, two Edgar Awards, and one of the most enduring characters in crime fiction, James Lee Burke is a titan among mystery writers. But maybe we should just call him a writer

Kyle Johnson

Before the day James Lee Burke handed me the almost comically long-barreled Buntline revolver and showed me what I would be shooting at with it, I’d never, not in the fifty-seven years I’d been alive, held a gun before. Armed with this knowledge, he had made sure I was pointing the gun in the direction opposite of wherever he happened to be and showed me how to load it, how you bring the trigger back halfway—where the phrase half-cocked comes from, he told me—and open the loading gate, centering the chamber, inserting the bullets, turning the chamber six times until it’s full. James Lee Burke is seventy-nine and he will be seventy-nine until December. He hasn’t hunted in fifty years, but he’s collected guns since he was a kid. He’s also collected coins, minié balls, and arrowheads. The guns—pistols and rifles from the Civil War, a Thompson .45 like the one Dillinger used, an Italian Carcano—are on display in a locked glass case in his hallway, surrounded by hundreds and hundreds of books. Don’t let his arsenal give the wrong impression, though, because he’s a gentle man. Though he’s created some of the more violent characters in American fiction, in his real life he’s an old-school guitar-playing pacifist whose work gives voice to those we might not hear above all the sound and fury. If Woody Guthrie had turned out to be a novelist, he might well have been James Lee Burke.

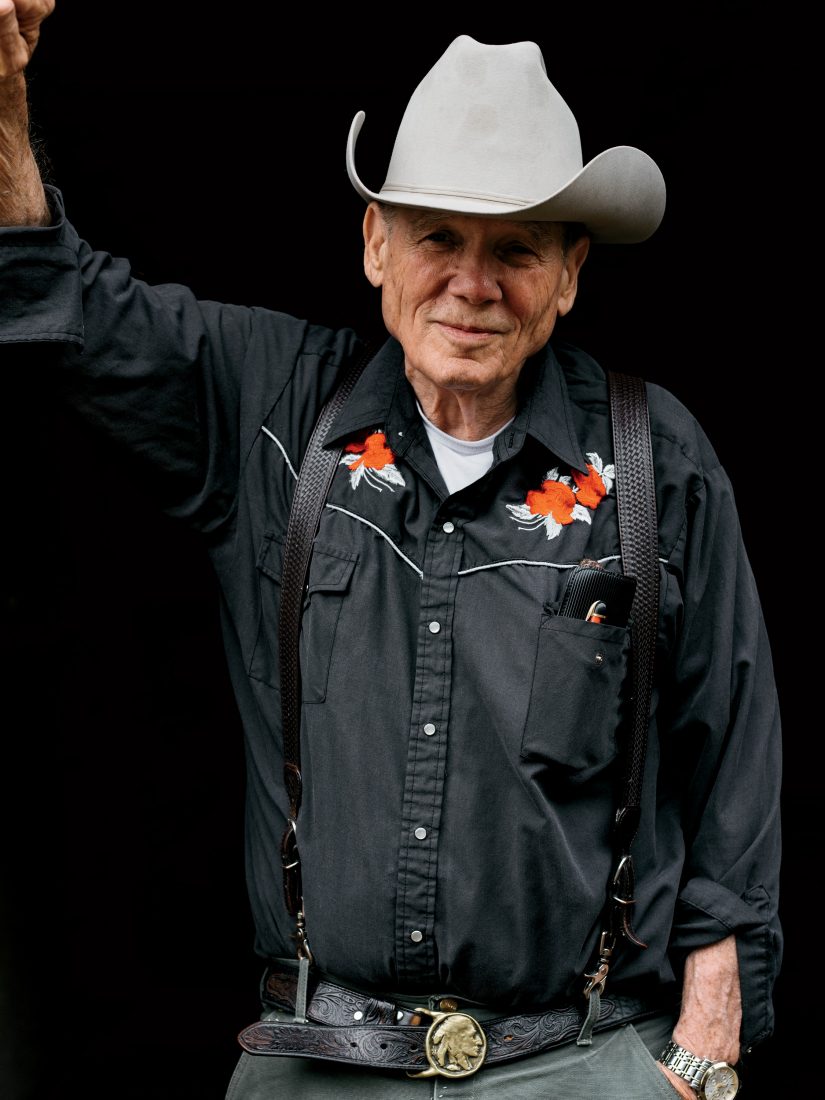

We were in the woods behind his house in the billowing, parabolic hills at the base of Montana’s Blue Mountain, not far from Missoula. It was so quiet we could hear a grouse flutter its wings in the underbrush. He had lined up a half dozen Maxwell House coffee cans. Big coffee cans, like paint canisters. He was wearing his cowboy hat and leather suspenders, his belt buckle an oversize Indian Head nickel, and we both had on ear protectors. He shot a couple of the cans to show me how it was done, bouncing them into the brush. Then he handed me the gun, gingerly, and I did exactly what he did, but failed to achieve the same results. I don’t know where my bullets went, but they didn’t violate the space anywhere near the ginormous cans.

“You know what?” he said. “We’re at a bad angle.” He walked up the hillside to move the cans ten or twelve yards closer to me, close enough for me to read the fine print along the bottom. Twelve to twenty-four bullets later, I hit one.

“You’ve got this!” he said. “You’re a natural. You’ll be better than me soon. Those cans had better watch out from now on.” In addition to being one of the most prolific novelists working today, he’s also one of the humblest and a really good liar.

We kept at it and still the cans had nothing to fear from me, and I suspect we would have been out there a while longer if the FedEx man hadn’t pulled up in the driveway. He stepped out of the truck with a cardboard box about the size of a toaster oven.

“Just set it on the porch!” Burke calls out, and then “Thank you!” and then, to me, softly, tremulously, “I bet that’s my novel.” His voice isn’t quite gravelly, but it’s rough, dusty, gruff but genial, sort of what Santa would sound like if he lived in Louisiana for a long time. “The advance reader’s copy, they call it. The ARC. I haven’t seen it yet.”

So we pack up the Buntline and all the accoutrement, and I follow him down the hill and into his house to open up the box; Pearl, his wife of fifty-six years, has brought it inside. He sets it on the desk in his office. Books line one long wall, and windows fill another. His two Edgar Awards for best novel—ceramic busts of Edgar Allan Poe, given by the Mystery Writers of America—flank his Grand Master Award for lifetime achievement, which is a slightly bigger ceramic bust of Mr. Poe. Even though this is his thirty-fifth novel, which means he’s done what he is doing now thirty-four times before, he takes the box cutter to it with the keen breathless excitement of a kid.

The Jealous Kind, it’s called, the last novel in a trilogy about the Holland family that began with Wayfaring Stranger. The series takes place in Texas, where Burke was born. This one is a novel of the fifties, a decade he feels only Rebel without a Cause has accurately portrayed. As Aaron Holland Broussard, the narrator, says early on: “It’s not the way everybody thinks. Not one person I know listened to Frank Sinatra or Bing Crosby or Perry Como. We thought their music was shit and Lawrence Welk was water torture.”

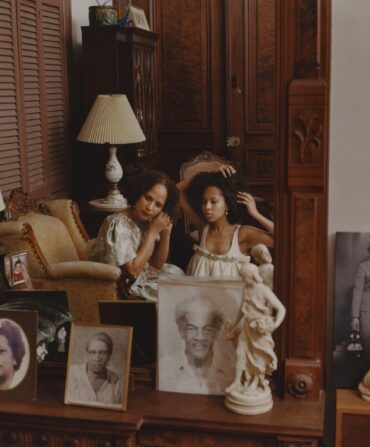

Kyle Johnson

The author at his writing desk, surrounded by family photos.

“These books are the best books I’ve ever written,” Burke says, “hands down.” He holds the book up. “Look at it.”

We look at it. He glows. He might have been ten years old and this his first Schwinn. The title is a deep crimson against a black backdrop, and there’s a blonde in pearls and a sparkling dress that seems destined to be taken off.

“I love this.”

Pearl takes a peek.

She smiles. “It’s nice, but it doesn’t look like one of your novels,” she says.

“It’s different,” he says. “But no man or woman is going to be able to walk past it without stopping.”

He carries it around with him for most of the rest of the day. That night we all go out to dinner at an authentic Montana steakhouse and eat beneath the head of a giant taxidermied moose. We go back to their house for fresh cherries and we eat them and then say good night. As I’m driving back to the hotel, the car ahead of me slows down so a goose and her five babies can cross the road. Almost all of them make it.

His thirty-fifth novel. I admit to getting caught up in that number. As someone who in twenty years has produced six measly novels and a kids’ book about a cat, I felt like I’d been sleeping on the job. As Jim Burke will tell you, though—and it’s hard not to call him Jim after being with him for about five minutes—it’s not about quantity. It just can’t be helped, though—when you work every day of the year as he does, the pages mount up. He doesn’t even take vacations and doesn’t seem to understand them or what they’re for.

Others have written more novels, but few have written so many so well. Burke is best known for being a mystery writer, and his plots are electric. But he’s also created a character in the darkly philosophical Dave Robicheaux who is as durable as Atticus Finch and Willie Stark. For those who are coming late to the book group, Burke has written twenty novels featuring Robicheaux, the sheriff’s deputy in New Iberia, Louisiana, who book to book manages to get caught up in various criminal enterprises. Just when you think it can’t get any worse for him, it gets worse; it’s a tragic spectacle, man’s inhumanity to man. Robicheaux can never quite win the day—wickedness may be stalled, but it’s never defeated. The man has lost a lot. But Robicheaux isn’t drawn from the legacy of Chandler, Hammett, or Spillane: Burke never read them. His P.I. arrives straight from medieval theater, the morality play Everyman, and the good Knight in The Canterbury Tales—in other words, all that stuff Burke studied in graduate school. Robicheaux is meant to be a tragic hero, a fearless man for whom a little fear might be a good thing.

“He takes chances that hurt him and sometimes hurt his family,” Burke says. “But they’re the kind of chances every person who really engages in the struggle of good and evil will have to incur. No way around it.”

Burke knows evil. Early in his career, when he was struggling to get his work published, he was, among many other things, a caseworker for parolees in Los Angeles and a police reporter in Louisiana and a recorder of music in Angola Prison, so he’s seen it all from deep inside the heart of darkness itself.

We think of the Robicheaux books as mystery novels, but that’s really just our own lazy shorthand, our need to try to fit everything in the world into its own genus and genre. We make the same mistake when we say Burke is a Southern writer. He was born in Houston and lived in Louisiana on and off for decades, so he is of the South, certainly. But it would be less specific and more exact to call him, simply, an American writer.

Kyle Johnson

Mountain Time

Burke with three of his four horses at the ranch.

Burke hasn’t always been a best-selling novelist. There were years when he couldn’t get his work published at all, and more years when the novels he had published went out of print. So he and Pearl have followed work wherever it took them, from Florida to California. He put himself through college partly by working as a landman for Sinclair Oil, and then went to graduate school at the University of Missouri, where he earned his master’s in English literature and, more important, met and married Pearl in 1960. It’s there he studied poetry with John Neihardt, author of Black Elk Speaks. He drove a truck and was a social worker on Skid Row in L.A. and a land surveyor in Colorado. Pearl worked as a librarian and took care of a family of four children. He taught at five colleges before finally getting on a tenure track at Wichita State University.

It was Black Cherry Blues, his third Robicheaux novel, that changed his life. His publisher needed him to go on tour in the fall, right when classes started. He couldn’t, he told them; if he missed a semester, he’d lose his tenure. But someone at the publishing company said, “I promise you, Jim. If you do this tour, you’ll never have to teach again.”

Promise kept. Since Black Cherry Blues, published in 1989 and winner of the Edgar Award for best mystery novel, Burke has been on the New York Times best-seller list almost every year. You can tell a writer is doing well by looking at the cover: When his name is twice as big as the title, he has officially arrived.

Let’s take a moment simply to admire his writing. This is from his first Robicheaux novel, 1987’s The Neon Rain: “Mist hung in clouds on the river’s surface and around the brush-choked pilings of the bridge; the air itself seemed to drip with moisture, and the shale rock in the parking lot glistened with a dull shine as the pinkness of the sun spread along the earth’s rim.” Echoes of Steinbeck, Hemingway, Faulkner. Maybe we can even hear something of his cousin, the late Andre Dubus.

And this from The Jealous Kind, his latest: “The juke and barbecue joints were loud, the doors wide open, the elevated sidewalks inset with tethering rings and littered with paper cups and beer cans, rust-stained where the rain spouts bled across the concrete.”

I can think of only a handful of writers whose work clears the high bar for three decades. Burke is one of them. The only thing undermining his credibility as a literary writer is his success, his sales figures. In America we can’t allow an author to be both popular and good. But Burke is.

And then there are the plots themselves. He’s come up with hundreds of them. Two books of short stories, thirty-five novels—and most of his novels have more than one plot snaking through them at a time, intertwining, winding and unwinding like coiling wisteria vines.

Where does he get these story lines?

Without hesitation, he answers: “They’re true.”

His stories are drawn from history, from his own family, from his time at Angola, on Skid Row, working with police departments. Corruption, ineptitude, vicious criminals, lazy cops, fearless heroes: He’s seen it all, and he’s heard it all, and he says the reality is even more sordid than the sordid versions in his stories.

“It’s the voice of the characters,” he says. “That’s what comes from somewhere else. It’s something I’ve never understood. I have blackouts sometimes, and have no memory of having written what I’ve written. Wasn’t it Michelangelo who said…” He pauses, excavating the quote and dusting it off so he gets it just right. “‘Every block of stone has a statue inside it and it is the task of the sculptor to discover it’? I think the character lives in the trunk of the tree that becomes the paper you type on.” He laughs. He has notebooks all over the house, handy to write down the sudden surprise sentence, the inspired idea, the revealing plot turn that might come to him on the way to bed or to feed his horses. His characters wake him up in the middle of the night to talk to him, and he listens. He reports what they tell him and we read about it later.

At seventy-nine James Lee Burke is sharper than a penknife. He seems to remember everything that’s ever happened to him, everything he’s read. He can tell a story—but never just one. The words fall like rain into a river, and the river flows with asides like tributaries eventually meandering back to the main. Fun fact: He’s a great impersonator—Dizzy Dean, Clint Eastwood, William F. Buckley, Jr., Jack Kerouac, Mary Astor, Jim Folsom. He can describe Civil War battles as if he had choreographed them himself. His great-grandfather fought in that war, and a picture of him dominates Burke’s office like the official spirit of the past. Burke has a metaphysical string and it’s tied to history, to family, to the before, during, and after of how he and the rest of us ended up here, at this peculiar and dangerous moment in our history.

And the South for him—the Texas of his birth, the Louisiana he grew up in—that’s in the past as well. He left it for Montana, and he may not return. “Wolfe was right,” he says. “You can’t go back.”

So many of his novels deal in one way or another with the despoliation of the land. In his 2013 Light of the World, the twentieth Robicheaux novel, one murder leads to another, which leads, in Burkeian fashion, to a much larger plot of corporate profiteers ruining what was once a pristine landscape. This isn’t just fiction to Burke. He’s watched the Louisiana of his youth disappear.

“It’s changed,” he says. “The respect for the natural world that used to be there is gone.” And he wonders if we’re going to lose it all, all the greens and blues of the world. “The context for our survival exists now,” he says. “The environment is changing, and you can argue about how much of it is our doing. But there are choices we have to make, and we aren’t making them. People aren’t ignorant, not at all. But there’s been a collective decision to be ignorant about this. This is a crossroads moment in history. We’re living in it.”

His world looks different now. Driving down the two-mile-long dirt and gravel road leading to his home is like driving into a dream of what the world can be. Spruces scattered and clinging to a sloping green hillside. Three open fields, and as many horses—four—as he has children. One of his children, Pamala, is his social-media guru/publicist, and has been for the last sixteen years. She’s also his first reader. Another daughter, Alafair Burke, is a best-selling novelist herself. The Jealous Kind is the last of the trilogy, and he’s not sure what will come next. Maybe another Robicheaux novel, but maybe not. He doesn’t plan that far ahead.

We didn’t plan that far ahead either. My first day there he showed me how to shoot a gun—an unplanned experience—and on my second he showed me how to play a few old songs on the guitar. He strummed the Martin, I picked at the Gibson. He sang “Folsom Prison Blues,” “The Wild Side of Life,” a couple of others. He does remind me of Woody Guthrie when he sings, with his unschooled and heartfelt twang and wail, his old green army pants held aloft by his indispensable leather suspenders. He’s not playing the part of one of our finest novelists, because I don’t think he knows how to, and wouldn’t if he did. Yes, most writers dream of having their name in forty-eight-point font on the covers of their books. James Lee Burke doesn’t care about that, though. He already knows who he is.