Southern Masters

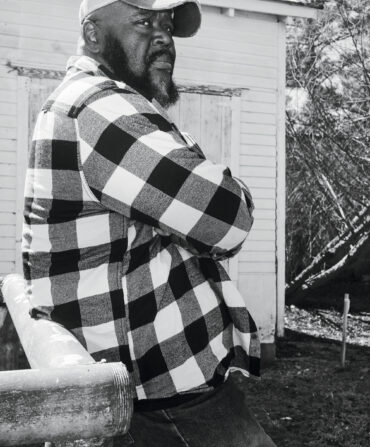

Lonnie Holley

With a gift for seeing meaning in the things others throw away, Lonnie Holley is showing the art world that beauty is where you find it

Photo: David Raccuglia

“This is the smallest thread,” Lonnie Holley says, holding up one red fiber, as thin as a hair. “It can matter.” He lets go and the string blows in the wind, part of a mobile Holley has sculpted from a coat hanger, a root, the lid of a tin can, and two seashells glued together. It hangs outside of an Atlanta storefront that was once a pizza parlor, among other things, but now serves as Holley’s art studio. The doors are open to an interior so filled with found material—Styrofoam, animal bones, tree roots, two old radios, stacks of stone, a web of wires strung from the ceiling—that some of it is tumbling out the door. It’s just trash, waiting to be picked up.

Yet look a bit closer. What has emerged begins to transform. Those Styrofoam pieces nearby reveal themselves to be carved faces. In plastic water bottles on the windowsill, you find both seedlings and holes in which birds can nest. The blue plastic sheet flapping in the breeze beside you has a handprint painted on it with the word HI in its palm; as the wind blows, it waves right at you. All around you, what was all just trash at first glance is, before your very eyes, becoming something else entirely.

This is the world of Lonnie Holley.

If Charles Dickens had set his novels in the Jim Crow South, Holley might have been his finest creation. Born in 1950 in Birmingham, Alabama, Holley counts himself as the seventh of twenty-seven children. As he tells his life story, by the time he was four, his mother had already given him to another woman, who then traded him to yet another woman for a pint of whiskey. At age seven he was hit by a car, dragged for several blocks, and left unconscious for three months. He spent two and a half years in the infamous Alabama Industrial School for Negro Children at Mount Meigs, where he was beaten often and severely. As a young man, Holley spent years working odd jobs, including time in a kitchen at Disney World in Orlando, before returning to Alabama in his late twenties. It was here that he made his first art. He was twenty-nine years old, and a niece and a nephew of his had died in a house fire. His family couldn’t find the money to buy grave markers, so Holley decided to make them himself. He salvaged industrial sandstone from a metal foundry near his sister’s house and, using a knife, a spoon, and a fork, carved it into two tombstones. Soon, he had created so much sculpture—from sandstone as well as other found materials—that he had transformed his property, near the Birmingham airport, into what was essentially one full acre of art.

“I love my brain, man, but it’s been through an awful lot,” Holley says. “I had to use art to keep me from crying. I had to bring it all out of me and put it on something. So my art was that. I wasn’t able to write all about it. I was braining all about it.”

Imagine the most curious, compulsively creative person you know. Put him through years of hardship, subject him to racism and poverty, and give him no creative outlet or medium with which to express himself. In many ways, this is the space in which I imagine Holley found himself as a young man. Someone with a writing background might have turned to essays, fiction, or journalism. An artist with access to traditional media—canvas, clay, photography, or even video—might have explored those paths. Holley had none of these. What he did have, in addition to his extraordinary mind, was an eye singularly trained to see the potential in items the rest of society had cast off.

For a time, Holley’s boyhood home was located in the odd cultural nexus between the Alabama State Fairgrounds, a racetrack, and a drive-in movie theater. At age five, he got his first job: picking up garbage at the drive-in. Here is where Holley first began to see the potential of items whose worth, to most people’s eyes, was nothing.

“I would prefer to take the trash and make it meaningful,” Holley says, perhaps also stating a metaphor for his own life, which many people in the Alabama of his youth might also have considered as having little worth. “With thrown-away materials, I’m doing the same thing the potters or sculptors of early stone were doing. I am making things, like what Malcolm [X] says, by any means necessary.”

One morning, as we walk across a parking lot outside a coffee shop in Atlanta, Holley’s instinct to glean kicks in. He stops to pick up two pieces of mulch. He taps one against the curb, testing its structural worth. Both make the cut. They go into his pocket. Later, in another lot, he plucks three large leaves off a Royal Empress tree growing from the cracked foundation of a warehouse. He lifts a gnarled root from the dirt. These too come along with him, but, by accident, he leaves them in my car. The next day, when I return them to him, he steps onto the sidewalk outside his studio and sets one leaf in the sun, then lifts the root above it so that its shadow lands perfectly in the leaf’s center.

Photo: David Raccuglia

Holley outside his Atlanta art studio.

“Stand here,” he says, directing me to his side. “Take a picture of this.”

I raise my iPhone to shoot, but before I do, Holley moves me into a better position.

“Over here,” he says. “And now, look. See? It looks like a lion, rearing up on his back legs.”

Again Holley has worked his magic—the root has indeed created the perfect silhouette of a lion contrasted against a bed of pure green, made from the leaf below. The image is right there in front of me and I hadn’t even seen it.

Holley’s compulsion to make things seems impossible to stop. His sculpture-filled property in Birmingham was bulldozed after the Birmingham Airport Authority acquired it via eminent domain (though Holley says the land is still undeveloped). He was driven out of his next home in Harpersville, Alabama, after being shot at by neighbors who Holley says were related to the original owners, who had lost the home in a drug raid. And yet, like some resilient strand of artistic kudzu, Holley just keeps regenerating and taking over whatever space he occupies. Now sixty-five, Holley was recently diagnosed with prostate cancer, for which he has been receiving treatment, but he remains incredibly robust and productive. His new apartment in Atlanta is so filled with his creations—so much hangs from the ceiling that in places it is difficult to stand—that it feels more like a web than a series of rooms.

In late 2014, the Metropolitan Museum of Art acquired three Holley sculptures for its permanent collection. In the art world, there is perhaps no greater validation. This followed acquisitions by the Whitney and the Smithsonian, to name just a few of the great museums that now hold Holley’s work. This year, the Halsey Institute of Contemporary Art in Charleston, South Carolina, mounted a major solo exhibition of his sculpture (on display through October 10), along with an accompanying book, including an as-told-to autobiography of Holley by the National Book Award winner Theodore Rosengarten.

“I would call it late,” Holley says, of his increasing recognition, “but on time for the future.”

Along with the wider appreciation of his art has come the emergence of Holley’s successful music career. Though he says he always sang, he released his first album, Just Before Music, in 2012, followed by a second, Keeping a Record of It, in 2013. Critics universally lauded both for their unconventional beauty and seemingly shot-out-of-nowhere singularity. He has performed with the likes of Daniel Lanois, Bill Callahan, and David Byrne, among many others, and is in high demand on the festival circuit.

“They are Siamese twins, coming from the same factory,” Holley says of his production of visual art and music. And like his visual art, Holley’s music is surprising and unusual. He improvises his songs anew at each performance, inspired by a set list of phrases written to spark various trains of thought. His voice conjures elegant melodies at times so catchy they stick in your head for days.

To many, the roots of Holley’s art and music are unaccountable. Where did this come from? How did this happen? The difficulty in fitting Holley into a preexisting category is in large part why he is so often classified as an outsider artist, a term widely applied to those who are self-taught or fall outside of the mainstream art world, but one that has also been criticized for marginalizing an artist’s work. To be deemed an outsider, after all, means that someone else has created an inside.

“His art doesn’t have a category,” says Mark Sloan, the director of the Halsey Institute. “Lonnie is in a category by himself.”

Still, Holley is surrounded by labels—outsider, folk, self-taught, visionary, mystic. The list goes on.

“All those things fit me like an ill-fitting suit,” Holley says. “And I’ve worn many suits in my life.”

When I ask what kind of artist Holley thinks of himself as, he answers immediately and emphatically: “I’m an American artist.”

That Holley’s work has found its way to museums around the country is itself a story. In 1986, William Arnett visited Holley’s acre of art in Birmingham, a moment that changed both their lives. Arnett is the pioneering founder of the Atlanta-based Souls Grown Deep Foundation, home to perhaps the country’s preeminent collection of African American vernacular art. Known for finding artists well outside the mainstream, Arnett has at times raised controversy by challenging the art-world status quo, as well as around the question of whether such artists have been taken advantage of. Holley feels strongly that, in his instance, such is not the case. When together, the two men talk shop and banter like an old married couple. “I love you, Bill,” Holley says one afternoon, pointing across a table at Arnett. “I want to be the best artist I can ever be. And this man gave me that chance.”

Photo: David Raccuglia

Man of Steel

Holley tinkers with his sculpture Adding Seats for Y'all at the Souls Grown Deep Foundation, in Atlanta.

Arnett was the force behind the wildly successful Gee’s Bend quilt exhibition, among many others. The three Holley sculptures now in the Met’s collection were part of the museum’s acquisition of more than fifty works by Southern African American artists donated by Souls Grown Deep. An exhibition is scheduled for the fall of 2016. But at the time Arnett first visited Holley, he was only a nascent collector.

“That changed it all,” Arnett says. “When I met Lonnie, I knew. I was like wow! It wasn’t what he said, although that was fascinating; it was what he did.”

At the time, Holley’s figurative sculptures—those featuring faces, commonly out of sandstone—were easy for anyone to identify with. They are evocative and playful, many revealing hidden faces embedded in and around other faces, with more shapes—houses, slave ships, animals—intertwined. His found-object sculptures, however, were harder for viewers to digest. While to some they were nothing more than piled junk, Arnett saw the assemblages for the highly deliberate works of art that they were.

“It required no mystical understanding of truth,” Arnett says. “Great art doesn’t need a textbook to explain it. You can’t miss it.”

“I was like good night!” Holley says. “This guy is really seeing what I’m doing better than anyone else I’ve entertained.”

When Holley discusses his work, he likes to tell you what he calls “the definition” of each piece, going over each element, no matter how minute, and explaining what it means in relation to the others, much as an author might carefully consider each word or paragraph in an essay. Every feature—each bend of wire, piece of string, empty bottle, or metal rod—is imbued with meaning.

“I’ll see a stone; Lonnie will see prison labor in the eighteenth century,” Arnett says of Holley’s ability to see the narrative possibilities in the least likely of objects.

The sculptures generate a different kind of aesthetic satisfaction than that of more decorative art—a reward that might be less immediate, but one that increasingly reveals itself the more you learn to pay attention to the exact materials we have so often been taught to ignore.

“My beautification is not for beauty,” Holley says. “It’s not for anybody’s wall. It’s for their brain.”

And it does affect your brain. After dropping Holley off at his apartment one afternoon, I stop at an intersection beside a huge oak that has recently fallen over. Yellow caution tape surrounds it, enormous splinters lifting into the air from the broken trunk. It’s just garbage now, soon to be removed by a crew. But then the scene starts to reveal itself to me in a way it never would have before. The yellow tape frames the broken tree like a ribbon of stage lights. The sky is stenciled into jagged pieces between the shards of the trunk. It’s intricate and colorful and speaks to years of magical growth and one moment of violent action. It’s as if Holley has infiltrated my brain and is directing it to perceive new and singular messages. I stay on at that stoplight a moment longer than needed, blindsided to find myself looking at such a giant piece of trash and thinking wow, that is beautiful.