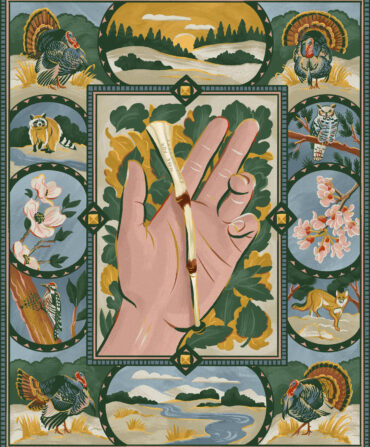

Land & Conservation

Squeeze Play: Pythons

They’re big, they’re breeding, and they don’t belong. So to combat the invasive Burmese python, Florida officials invited all comers to take on the Everglades’ most notorious outlaws

Photo: Gately Williams

Somewhere behind us in the murk of the canal comes a watery crash and the gnashing of teeth. Twelve-year-old Morgan, dozing on the bank, panics and scuttles up to safety, swinging his flashlight back and forth. The finger of light illuminates a scene that looks like a charcoal-etched daguerreotype, shades of gray and black, with buttonwood trees reflected in the silvery water. The only color is the glowing red cigarette eyes of a half dozen alligators spooked by our noisy presence.

“Goddamnit!” says Allen Schneider, turning to his young son. “We might have a snake here and you’re fooling around with those gators. Get away from the water!” A tangerine waxing moon hangs in the saw grass. Schneider creeps forward to an inert S shape lying on the trail. He brandishes a snake hook that looks like a giant dental tool. It’s the least menacing of the weapons weighing down his diminutive five-foot-six frame. A 12-gauge shotgun hangs from his back. On his right hip is a 9mm pistol, on his left a .22 Magnum revolver. In case all those fail, he carries three throwing knives in a neat pouch. Schneider is a former Florida Keys charter captain who now works as a nuisance animal removal expert. I’m here in the Everglades with him and his son for the Python Challenge.

Photo: Gately Williams

Snake Charmers

Hunter Allen Schneider.

Schneider approaches the S shape and quickly pounces, pinning its head to the ground. On closer inspection, however, it is not a Burmese python, our desired quarry. It is a very angry water moccasin. “Dang!” he says, panicking slightly. “These are the only snakes that will actually come after you.” He gingerly releases his grip and winces like a novice defusing a bomb. The snake rears to strike. Schneider hooks it around the midriff and sends it hurtling into the alligator-infested canal. On we march, into the quickening Florida night, looking.

Schneider is one of a heavily armed posse, eight hundred strong, assembled this past winter for the takedown of one of Florida’s most notorious and elusive outlaws. Hiding out in the deepest parts of the Everglades is the Burmese python, a species whose invasion of these parts was swift.

Back in the 1980s and early ’90s, southern Florida became a hub for both cocaine trafficking and reptile smuggling, with considerable overlap. Often drug traffickers took part in importing exotic species—some going so far as to stuff boa constrictors with cocaine. Reptile breeding farms started. No end of wannabe Tony Montanas ordered Burmese pythons to parade around South Beach or to keep in their stucco mansions to amuse guests. A five-foot-long Burmese baby is manageable. But the snakes grow to as long as twenty-three feet, as thick as a telephone pole, and as heavy as two hundred pounds. Many an alarmed python owner released reptiles into the Everglades, a habitat ideally suited to the jungle native. Making matters worse, 1992’s Hurricane Andrew reportedly destroyed some commercial python breeding facilities near Homestead, a town at the southern end of the Miami megalopolis and the edge of the ’Glades, allowing their once-captive livestock to slither off into the welcoming sea of grass.

Release Burmese pythons into Connecticut, say, and the cold-blooded creatures would perish in the first cold snap. But in southern Florida, they thrive, laying as many as a hundred eggs at a time. Credible estimates of the wild python population there range from 5,000 to 100,000, numbers that leave plenty of room for disagreement. Some think even the high end of that range falls short. “We’ve hit one stretch of canal bank over and over,” says J. D. Willson, an assistant professor of biology at the University of Arkansas who has studied the snakes’ proliferation. “And we’ve pulled eighty pythons out of there. The science has just not caught up with accurately estimating how many of these there are. I would say that there are hundreds of thousands rather than tens of thousands.”

Photo: Gately Williams

A full-grown Burmese python can weigh up to two hundred pounds.

For years the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) has flailed away at the problem, allowing hunters to remove snakes, offering amnesty days when pet owners could turn in unwieldy pythons, and, in partnership with the Nature Conservancy, setting up both a hotline for sightings and a Python Patrol. The month-long Python Challenge in January and February, Florida’s first, has upped the ante, attempting to warn the public of the hazards of invasive species by using the python as the poster boy. It is also a giant experiment. The organizers want to see if offering financial incentives to the public—$1,000 to the capturer of the largest python; $1,500 to the hunter who catches the most—can successfully cull the fast-multiplying population. They also hope that harvesting large numbers of pythons in such a short time will give scientists precious insight into the snakes’ eating habits and preferred habitat. Participating hunters have paid $25 apiece for permits that allow access to four Everglades wildlife management areas.

The 2013 Python Challenge is launched to the strains of “Brown Eyed Girl,” outside the Hurricane House at the University of Florida Fort Lauderdale Research and Education Center, in Davie. A carnival atmosphere prevails. Although few of the entrants have hunted snakes before, they have come girded for battle, spurred on by YouTube videos showing giant pythons fighting to the death with alligators. Some look like extras from Pirates of the Caribbean, with large, suspiciously new-looking knives jammed into their belts. Others suggest a fondness for SEAL Team Six, dressed in neatly ironed camo with mossy oak do-rags and shiny black combat boots. Members of a motorcycle gang, the Swamp Rats, drift past on Harleys. One red-haired giant of a man has “Pepper” tattooed on his neck. A man at a stand sells python skin pants and offers to tan snakeskins. A chef cooks tacos made from snakehead fish, another invasive species. Reality TV producers are everywhere. One strides around on a cell phone encased in a faux set of brass knuckles.

From behind a magnificent silvered Wyatt Earp–style mustache, Jake Wierzbicki, a fifty-seven-year-old field engineer from Homestead, recounts the two times he has killed rattlesnakes with his bullwhip in Nevada and Arizona. “That leather goes at nine hundred and eighty miles per hour and breaks the sound barrier,” he says. “Turns ’em to mush.” He rocks back on his heels, showing off his $400 snakeskin boots. “Four layers of Kevlar,” he says, alluding to any venomous snakes he may encounter during his quest for pythons. “Ain’t nothing getting through that.”

Wierzbicki’s motivation seems not so much ecological as it is a vendetta. “If they weren’t damned, then God would not have them crawl around on their belly,” he says. “I mean, these things are killers.” He recalls the dreadful story of Shaianna Hare, a two-year-old up north in Oxford, west of Orlando, who was killed in 2009 by an eight-foot pet python as she lay sleeping in her crib. “When they go to eighteen feet you got a man killer,” Wierzbicki says. “I hate snakes.”

The media hoopla surrounding the event has led some to envision a bloodbath, with thousands of captured snakes—pythons hanging off trees at every turn. But not everyone. As the crowds thin, climbing into pickups and revving up motorcycles to light out for the Everglades, Captain Jeff Fobb of the Miami-Dade Fire Rescue’s Venom One—a unit that removes nuisance snakes and deals with bites—offers me a cautionary word while he cradles a twenty-two-month-old female Burmese. “These creatures camouflage themselves very well,” he says, flashing a smirk. “They escape when they hear trouble. You have hundreds of people crashing about. I think we’ll be lucky to see a hundred caught in the whole competition.”

Photo: Gately Williams

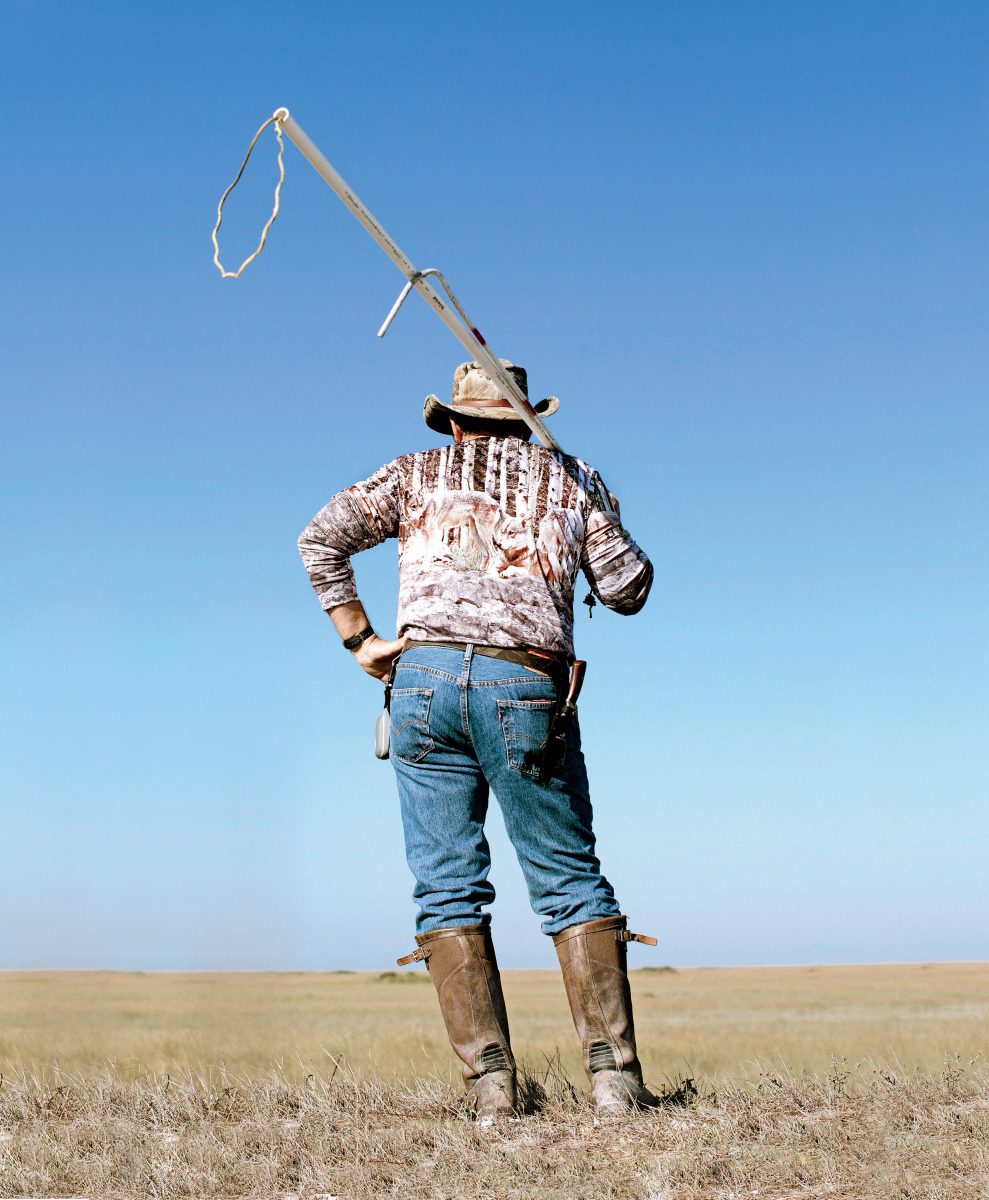

Showdown in the Swamp

Python hunter Jake Wierzbicki, loaded for snake.

The day after my unsuccessful hunt with Allen Schneider, we’re at it again. In the greening dusk, Schneider eases his heavily laden boat into the turbid water of Canal L67. “Here we go,” he says. “Into the heart of darkness.” Southern Florida has about 1,800 miles of canals, dug to prevent flooding and drain swampland for the region’s urban sprawl. We motor in to some marshy turf Schneider has scoped out for potential snake habitat. His spotlight illuminates deep burrows ripped out of the banks by alligators, where he says snakes sometimes hide. They’re empty.

Photo: Gately Williams

Wierzbicki in the Everglades.

We head several miles west before alighting on foot to hunt, pressing through treacherous pluff mud. We push through thickets of thorny trees jammed with cobwebs. Schneider leaves no stone unturned. He spots a deer track. “Pythons are ambush predators, so they’ll wait for other animals to follow down the trail,” he says. Other hunters have left plywood boards under bushes to lure in nesting mice and, in turn, snakes. Nothing. Schneider surges up piles of limestone, pulling out rocks covering suspected python lairs. Morgan leans in with his head torch. “Careful, son,” Schneider says. “If it’s a rattler in there, you’re gonna get bit.”

After many hours of plunging in and out of thickly forested banks, Schneider comes to a sharp halt in a dense thicket. “Shhh,” he says. “Notice anything?” At first nothing dawns. Then I realize that despite being out in the middle of the Everglades for well over twelve hours, day and night, we haven’t seen any mammals. Not one. “Ten years ago I used to come down here and see herds of deer, fifty or sixty, all over here,” Schneider laments. “I used to hunt here all the time. Now…zip.”

In February, Michael Dorcas, a biology professor at Davidson College, published the results of a study that suggests Schneider is onto something. Dorcas and his team found that from 2003 to 2011, observations of raccoons here decreased by 99.3 percent; sightings of opossums dropped 98.9 percent; of bobcats, 87.5 percent. The researchers found no rabbits at all. “We were sampling this same road in the Everglades, searching for pythons for three years, and started to notice the near complete absence of vertebrate animals,” Dorcas says. “We hadn’t even seen a raccoon for years. When the results of our calculations came back, we were astonished at the magnitude of the declines in many once very common mammals.” He concludes: “You’ll never hear me say this is definitively the python. What I can say is that both the temporal and spatial patterns of python occurrence and mammal declines indicate that it is highly likely pythons that are causing a decrease in mammal populations.”

By a pond filled with garfish, Schneider, Morgan, and I find a python skin. By a pile of limestone there’s the musky scent of a python. We surge farther. I slip down an escarpment of razor-sharp boulders, stripping skin off my elbow. We motor back to the dock empty-handed.

The next day we head to the Southern Glades Canal. Schneider guns the boat into the banks, and we climb through dense foliage. We’ve covered more than a hundred miles without spotting a python. What we do see everywhere are some of the invasive species that, according to the National Park Service and the FWC, have infested at least 1.7 million acres and cost the state some $500 million every year. We fight through thickets of Brazilian pepper that crowd out light, killing native plants. Old World climbing fern strangles cypresses. I start to notice what looks like pink bubble gum stuck to steel fence posts: the Giant African land snail. Pythons may be the most maligned, but they’re certainly not the only species disrupting the Everglades’ natural balance.

After three days, I have blisters the size of golf balls on my feet, a wasp sting, I’ve lost five pounds, and my skinned arm is healing all too slowly. Still no python. Unseasonably warm weather, often in the seventies, gives them no incentive to sunbathe. “The snakes have all the edge out here,” Schneider says. In the first three days of the Challenge, hundreds of hunters have caught only eleven. Members of a group called the Florida Python Hunters caught three the first day. “How can they catch three when over eight hundred people have caught nothing?” Schneider mutters.

One of the successful hunters is Dave Leivman, of Weston, Florida, aka Python Dave, who has hunted pythons on an individual permit for a few years. He hands in two pythons early in the competition, one of which bites him during a live interview on Fox News. (“Never turn your back on a python,” he later tells me.) The following day, an e-mail is sent to all Challenge entrants declaring that snakes must be handed in dead.

A gregarious, fleshy-faced man, Leivman has lived in the Everglades since he was two. When I visit his house after hunting with Schneider, he greets me at the door with five dogs snapping around his heels. He found his German shepherd, Elsie, way out in the ’Glades, just skin and bones, abandoned by a callous owner. A rabbit lives in the downstairs toilet. There’s a ball python, a smaller relative of the Burmese, in the living room.

Leivman has always caught native snakes in the neighborhood. Five years ago, when he caught his first python, he figured it was a fluke. Two years ago he started to catch them regularly. He’s an avid snake lover as well as a hunter and cannot bear to kill them. “It is not the pythons’ fault that they are here,” he says, his features darkening. “I would like to see them removed, but it has to be done as humanely as possible. I’m a little uneasy about letting the public do the killing.”

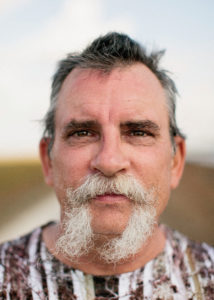

Photo: Gately Williams

Biologist and Python Challenge participant Nick Gadbois.

The next day I join Nick Gadbois, a mild-mannered environmental scientist and marine biologist who travels the canals taking water samples for a private company contracted to the FWC. He sometimes catches snakes while working. “Goddamn yahoos,” he says, eyeing a pickup filled with men prowling the berm over a canal. Gadbois works with Bob Hill, a sixtyish man who has become an Everglades legend. There are images all over the Internet of Hill catching monster pythons, including one that had eaten a full-grown deer. Both men have witnessed epic battles between pythons and alligators. The giant snakes wrap the alligators and then slowly tighten their grip each time the gator exhales. When a python swallows something that big, its metabolism speeds up forty times and its digestive tract doubles in size. The heart nearly doubles as well.

“I think snakes are pretty cool,” Gadbois says as he shows me the carcass of a python he caught a while back. He’s leaving it in the sun, letting rodents and bugs strip its flesh so he can preserve the skeleton. A Burmese python can unlock its jaws to accommodate the largest prey, he says, pushing its windpipe up and off to the side. Pythons are formidable swimmers and can stay underwater for thirty minutes.

During the Challenge, Gadbois and I hunt for days, and often at night. We hit spots so remote that we find remnants of Santeria ceremonies: red cloths, candles, offerings to an unseen deity. “Spooky,” Gadbois says. Still, we are unlucky. Gadbois seems discouraged by the sensational turn the competition is taking. As the media storm intensifies, more hunters sign up, bringing the total to around 1,200 a week into the hunt. Allegations of cheating feed the rumor mill. “Already they found coolers out on some of the tree islands with snakes in them,” Gadbois says.

With hunters eager to throw their rivals off the scent, there is no shortage of bluffing and misdirection. When we come across a pair of camo-clad men swinging machetes as they walk across a berm, Gadbois tells them that a massive python was spotted near a café not far away but managed to escape. The men frown and tromp back to their car. “Got ’em,” he says. “They’ll leave this area to me now.”

Given the dearth of snakes, I link up with yet another hunter in hopes of increasing my chances. Rodney the Python Hunter, as he calls himself online, is Rodney Irwin, a chain-smoking Floridian from Homestead, a place he calls “ground zero” for pythons. He’s a self-described “herper” (short for herpetologist), fascinated with snakes and reptiles. Irwin hunts from a red Ford F150 with a 12-gauge Remington and his giant Alsatian, affectionately known as Big Dog. Once they caught a green anaconda, which caused a local stir as scientists wondered if that species too had entered the Everglades food chain. “Just someone’s pet,” Irwin says.

We crawl around a deserted NASA facility formerly owned by Aerojet, a company that built rockets for the first space shuttles. Amid the giant, dilapidated factory choked with poisonwood trees, Irwin stalks with Big Dog at his side and the shotgun over his shoulder. Despite venturing out here every night prowling for snakes, Irwin is a realist about actually catching one. “You’ll probably never see a python while you are here,” he lets slip. “These things are very hard to find. And that’s the problem.”

Photo: Gately Williams

On The Lookout

Hunters often stalk pythons at night, when the snakes are most active.

Back at Irwin’s art deco house, we head out to where he keeps the small alligators he uses for children’s shows, one of his main sources of income. Deep in a garage, next to a speedboat on blocks, is a pen. Irwin rummages beneath the straw and pulls out a large black leathery lizard the size of a small dog. It’s an Argentine tegu, another invasive species. It looks angry.

“These things are going to make the python look like nothing when they get going,” Irwin says. Unlike pythons, tegus can survive a cold snap as low as thirty-five degrees, and they eat almost anything. “We may not have caught a python,” he says. “But I’m ready for the Tegu Challenge!”

By the end of the Python Challenge, 1,600 hunters have caught a total of sixty-eight snakes. The winner, Brian Barrows of Fort Myers, harvested six pythons for the top prize of $1,500. Paul Shannon of Lehigh Acres caught the biggest snake, 14 feet 3 inches. Included in the grand tally, a simultaneous competition for those who already had permits before the Challenge was won by Ruben Ramirez of the Florida Python Hunters, who snagged eighteen.

Although the low number of snakes caught surprised some, Frank Mazzotti, a professor of wildlife ecology at the University of Florida and one of the Challenge’s organizers, was not one of them. He first implanted transmitters in pythons back in 2005, in a bid to study their behavior. On occasion during the Challenge, he and his fellow researchers watched python hunters with bemusement. “We could see people walking past them all the time,” he says. “The other day five guys walked past one in a tree that we knew was there because of the transmitter.”

As Mazzotti sees it, the Challenge was a “scouting expedition” to discern the best tactics to combat the pythons’ spread. “I get to see who is good at catching snakes and who is good at keeping information,” he says. Once researchers have studied the results of the hunt, they can plot strategy. “Rather than the Challenge, which only happens a month a year, if there is a group that is good at catching pythons, can we incentivize them on a year-round basis? I’m in favor of whoever is best at this and getting them on my side.”

For some entrants, the Challenge had a wholly unanticipated effect. At the start of it, I met a silver-haired English professor from Colorado named John Calderazzo, who was caught up in the serpent-hunting fervor. “Nothing human in those eyes looking back at you,” he told me. He signed up to go out with a hunter and also ventured out on his own. At the opening ceremony, though, he got an opportunity to hold in his arms a thirteen-foot Burmese python. He marveled at its grace and power. Later, while hunting, he discovered that his heart was not in it. “I realized very early on that I wanted no part in the killing of pythons,” he wrote to me as we were both leaving Florida. “Even though I agree that a hunt might be a sound ecological response now that everything else has failed, it came down to this: They are such magnificent creatures.”