Conservation

Tangled Up in Indigo

Since first encountering an indigo snake as a boy, the author has been haunted by this all-but-extinct vestige of the Southern wild, once as much a part of the landscape as the longleaf pine. For fifty years he has walked the woods in search of an indigo, with an eye to the ground and, at long last, a little help from perhaps the only group in the world trying to save them

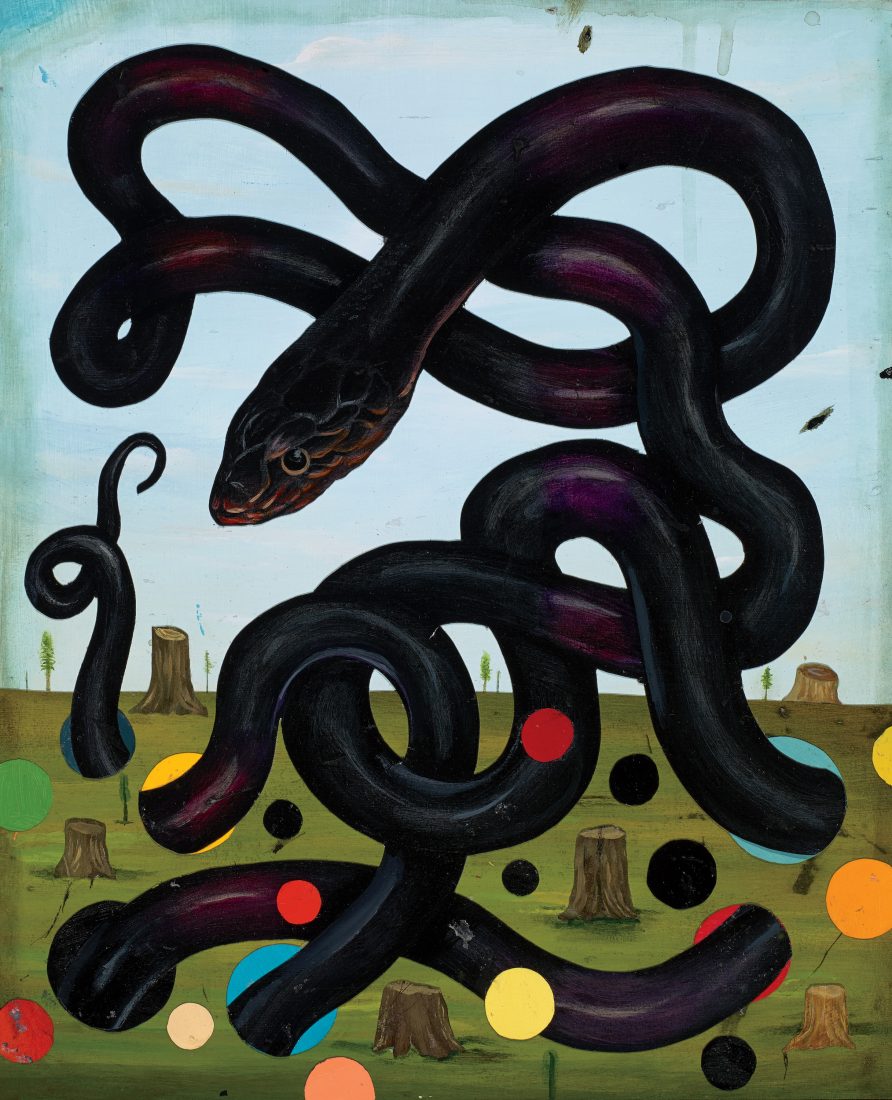

Illustration: Illustration by Jason Holley

How I Became a Fool for the Indigo

James Gregory’s father, we were told, was stabbed twenty-seven times in a shell parking lot outside a liquor store in Jacksonville, Florida, where, possibly, he worked. We never talked to James Gregory about it. We did not know James Gregory well. We put on a school play in which we surgically removed a tumor from a patient using backlit projection on a bedsheet to better show the ghastly tumor lifted from the patient. The tumor was a live six-foot snake that in the projection must have looked fifteen feet long. We got the gasp from the audience that we wanted. I like to think that the patient was James Gregory, and that yada yada we were exorcising a demon from him, but in fact I do not recall who played the patient and doubt that it was James Gregory. We did not know him well, and I do not even often think of James Gregory in this or any other context. I do remember that after the show the snake was enjoying his stardom until too many children touched and grabbed at him and it became a kind of rock star–fandom event that needed security and there was no security and the snake having had enough decided he was his own security and he bit Mike Wilkerson on the thumb, and Mike Wilkerson shook him off his thumb and in that jostle we dropped the snake, who crawled under a long leaning stack of metal chairs for surcease from his admirers.

And let us pause. We have a large snake under a long stack of leaning, heavy chairs. I am an agile twelve-year-old boy with a good sense of physics, which is what confers agility. The snake is under my charge. The snake has been put in my charge by my fifth-grade teacher, Shirley Brown. She has him because she has friends at the Jacksonville Zoo reptile house, whence he comes to her on loan. The snake will not be declared federally protected until 1978, but already in 1964 it is a rare animal. I have been allowed access to him to put him in the play. I am in charge and the snake has survived a fan event without security and is now under a ton of metal that can, with less jostling than dropped him to the floor, slide, shear, crash, and in my agile twelve-year-old brain cut him to pieces or merely crush him to one multiply bolused piece. The prudent thing would have been to put my foot on the rubber foot of the leading leaning chair to secure the stack and ask Mike Wilkerson to get the snake, or, if Mike Wilkerson had had enough of the snake, to have him replace my foot with his and get the snake myself.

Maybe prudence had been abdicated when we decided to pull a snake tumor out of a person onstage. I got down and into the chairs and maybe Mike did too, and we got the snake out without incident; he did not, that is to say, bite us in the face, which we were presenting to him perfectly had he wanted to. I already knew that the character of this snake was special, having handled him some before his stage debut (I posed with him outside the Jax Zoo reptile house), but I suspect his agreeable demeanor at this juncture may have spoken to me in my condition of emotional delicacy, a phrase I borrow from William Trevor and will explain. The snake had no more quarrel with Mike Wilkerson’s thumb. We got him into a secure cage and I had a nervous breakdown. Maybe that overstates it. The expression “burst into tears” understates it. Let’s say I was wracked by a sobbing that made it hard for me to breathe, or see much, but the little I could see included my teacher’s collapsing faith in me as her protégé. (She had called me this when introducing me to a man at a drugstore who was not her husband, whom I knew and liked, and my adult-behavior alarm had gone off.) In my sniff-heaving I could not begin to explain to anyone the vision of those chairs, the hair trigger those old beige rubber feet were, what one rung of chair could do to a snake let alone five hundred…and I watched Shirley Brown dismiss me, and thought something like, Well, this is of course regrettable, but she has no idea, hail-fellow-well-met with her drugstore dandies.

For fifty years I have thought only occasionally about James Gregory, sturdy Mike Wilkerson, or Shirley Brown. I have had no outsize breakdowns, just the steady march unto desuetude. But more than occasionally I thought about that giant purple friendly snake, and I have walked the woods looking for one. At first everywhere, anywhere, because they were alleged to be everywhere, and later in rarefied, special terrain, because they were supposed to be there, I walked the woods looking for an indigo, the gentleman snake.

Many parks in Florida have information kiosks with colorful enamel signs showing the special flora and fauna in the park. The gopher tortoise, the scrub jay, the indigo snake. At no park with an indigo snake on its kiosk signs could I find an indigo. If I asked rangers if anyone had seen one, no one had, or maybe someone had, some time ago, and where is that fellow, well he’s not here anymore. I finally realized that the thing had gotten so rare that if I was to see one of these snakes in the wild, alive, while I was alive, I was going to need professional help. (It is not easy to see one not in the wild. The Jacksonville Zoo still has a few, and I wonder if they are related to the 1964 snake; I was recently surprised to see one in the Nashville Zoo.)

How a Friendly Old Redneck Becomes a Fool for the Indigo

About the time of the snake play in Jacksonville, Fred Sulley was working construction in an early development of Orlando called Bay Hill and began noticing indigo snakes and realizing they were being displaced by the habitat destruction. “They had nowhere to go,” Sulley tells me. He began taking some home and turning them loose in his house. One, a male he captured at three feet who grew to eight feet, whom he named Big Guy, took up behind the sofa. “That was his place,” Sulley says.

When friends came over and sat on the sofa, scooching it into the wall, Big Guy would “get mad,” according to Sulley, and could expand and inch the sofa back out away from the wall with the people sitting on it. “They thought it was mechanical and I would say oh no, I got a big snake back there, and they would laugh. Then Big Guy would smell their shoes and pants to see where they had been, like a dog, and come out and raise up about four feet to look at them. Whenever that happened I never saw those people again!”

He credits Big Guy with exceptional intelligence. “Once I came in and put a bucket of KFC down and went to change clothes and when I came back the chicken was all over the floor. My lady friend at the time said we should throw him some chicken to see if he would catch it. We had been throwing him mice and rats. He caught them and he caught the chicken too.”

It’s been fifty years and Fred Sulley, whom a friend of Sulley’s lady friend at the time calls “just a friendly old redneck,” still misses Big Guy, who came to his end well away from the outdoor perils at Bay Hill. “Indigos,” Sulley says, “are affected by insecticide. All the snakes I had died of colon cancer. I had a roommate that had the place treated for bugs every month. Big Guy was smarter than any cat I ever had.”

How a Snake Nut Becomes a Fool for the Indigo

A snake enthusiast who has an indigo and calls herself snakemama posts this on Pet Talk:

I held an Indigo snake at a reptile expo about…nine years ago, and that twenty seconds changed my life…I HAD to have one.

They’re very unlike any other snake. First, they are unable to unhinge their jaws in order to engulf large prey, so they have to eat smaller prey items. Second, they have a FAST metabolism, so they eat (and poop!) frequently. He eats three or four small prey items a week. Third, they are smart. Grendel clearly recognizes me from any other person, and whenever I am in the room with him he keeps his head out, watching me. He doesn’t watch my husband or anyone else.

He’s incredibly docile, until he senses food. Then he becomes a maniac! He’s also beautiful…with big glossy black scales and an enchanting red face. He’s very expressive too. He makes little “huff” sounds of disapproval when I’m not taking him out of his tub fast enough or when I won’t let him go climb out of my reach.

She continues:

We got used to each other quite quickly. I DO have to let him know that I’m coming, if I surprise him by taking him out too quickly he’ll strike at me, but if I take it slow he’s completely fine. Soon, I started taking him out to climb trees!

In the wild, male Indigo Snakes may patrol quite a large territory, so I make an effort to get him out for lots of stimulation and exercise every day.

These snakes will eat ANYTHING they can get their mouths around. In the wild they eat a lot of rattlers and other snakes, but they also eat fish, birds, rodents, lizards, and anything else they can! This has caused me some problems…like the day I tried to wipe some spots off the side of his tub with a paper towel…

It can also be funny, like last week when I decided to offer him a bite of my pork chop and see if he liked it.

I have let snakemama go on because, dubious as what she says may look to the non–snake nut, everything she says is true. She can be called a snake nut if we may concede that the term is not always pejorative. It isn’t.

Photo: Greg Dupree

Drymarchon Couperi

A captive four-and-a-half-foot adult Eastern indigo snake named Guinness.

Strippers Were Fools for the Indigo

Before international trade made the python and the boa constrictor available, if you were a woman in the United States who wanted to remove your clothes and move suggestively for entertainment purposes, and you wanted a snake in your act, you wanted an indigo. It was huge, agreeable to your business, provocatively mobile, and its indigo iridescence, next to your white flesh, in the case of burlesque dancer Kathryn “Zorita” Boyd, was striking. And when you were not at work, you could take your business partner for a walk, on a leash.

I Had Better Define Snake Nut

At bottom, a snake nut is a person who has the chase gene, defined here by Jennie Erin Smith in Stolen World, her book about illicit reptile trade: “Levy, like Molt and the rest, possessed the gene that had caused him to chase after reptiles since he could walk…” The person with this gene may chase all reptiles, chase some reptiles, or be a hard-core snake person only. He, or she, may have the gene only recessively; she may be a botanist, say, with a casual delight taken in the reptiles in the bushes. There are good snake nuts and bad snake nuts. Here is a bad snake nut, again from Smith: “Bob Udell was a free agent now, roaming back and forth to Florida, returning with trash cans full of indigo snakes that he kept in his apartment.”

A bad snake nut trading in indigo snakes is one of the historical forces that have depleted the indigo to the edge of extinction. They were beautiful, they were friendly, and they were money. In scientific parlance, researcher Kevin M. Enge and colleagues write, “Collection of Eastern Indigo Snakes for exhibition purposes and the pet trade probably contributed to population declines in some areas in the past (Whitecar 1973; Lawler 1977), and although illegal collecting still occurs, its impacts on populations are probably minimal compared to those of habitat destruction and fragmentation.” Note the two probablies. A man in pursuit of the indigo today, seeking professional help, must be careful what kind of snake nut he appears to be.

As a boy I was a member of a club run by the famous reptile showman Ross Allen, and the club sent its members pseudoscientific papers mimeographed on construction paper with a three-hole punch. When I read that efforts to force a rainbow snake to regurgitate in order to study its diet killed the snake, I realized a herpetologist, if that’s what it took, I would not be. So my chase gene came to override my study gene, if I’d had one. I merely wanted then, and want now, to hold a snake, not make it throw up, or cut it open, or sell it. I am a good snake nut.

Turning Myself Over to the Professionals

I began by running into an old friend working in herpetology and telling him that I was on my see-an-indigo-before-I-die quest. He told me there were two beautiful women doing indigo research in southern Georgia and that I should hook up with them. Indubitably, I said, I want to hook up with two beautiful women who will to boot put me on an indigo. The friend was to send me an e-mail. I waited.

After a year I ran into him again. Waiting on the…I said. It’s coming, he said. Again it did not, and it dawned on me that this was all just possibly a bit too Odyssey to be true—two beautiful women, in the woods, were going to show a wandering stranger an extinct purple snake.

I wrote a writer I know, John Lane, with whom I once looked for snakes in a rock quarry near Spartanburg, South Carolina. John wrote a Chuck Smith at Wofford; Chuck Smith wrote me: I should contact Chris Jenkins, boss of an outfit called the Orianne Society, which, incredibly, was formed to preserve the indigo snake. Improbable an idea as an organization dedicated to saving a snake is, that it is, in this case, a society is perfect: A gentleman snake belongs in society. This is a society snake if there ever was one.

Photo: Greg Dupree

Orianne's CEO, Chris Jenkins.

I wrote Chris Jenkins from within the Orianne website and heard nothing. Maybe I had not managed to come off as a good snake nut. An organization saving the virtually extinct indigo snake might have a significant problem with, and be hypervigilant for, the bad snake nut. How to let Jenkins know I had held one snake in 1964 and was still haunted by it, and that I had no experience with trash cans full of indigo snakes?

I essayed one last go. I trod lightly:

Dear Chris Jenkins:

I’ve been referred to you via John Lane and Chuck Smith. I asked them where might I best stand a chance to see an indigo in the wild.

I wrote you earlier, to the Orianne site, perhaps going astray, and thought I’d try again. I am pondering, have been for years, doing a piece, possibly long, about the indigo snake as it perhaps symbolizes the peril of all things good in the world we have ruined….

Perhaps itself a bit spooky. But Dr. Jenkins responded:

Padgett,

I apologize if I missed your last email. I have ccd Heidi Hall and she can coordinate with you on the best way to get into the field with our staff to see an indigo….

Heidi Hall! Does that not sound like a beautiful woman? And she is in fact in Georgia working with the indigo. I am back in The Odyssey.

And Hall writes:

If you could give me a range of dates you would be willing to come out in the field I can start coordinating with our staff. I noticed you are in Florida….

And I am not only in The Odyssey, I am in the door.

Captive Propagation of the Extinct

It should be noted that I am about to witness animals that I deep down have believed extinct for nigh on fifty years. In my empirical view, they are extinct. I know that they are not, but they still are.

Before I go outdoors to see them, I go indoors. The facility in Florida that Heidi Hall has invited me to is a breeding compound outside of Eustis. The kennelman as it were is Fred Antonio. We enter a building marked Quarantine, which is for ascertaining that animals introduced into the breeding program are pathogen-free. The floors are concrete with a spectral speckled epoxy paint on them that squeaks of clean; the balance of the room is stainless steel and good lighting. We approach a steel rack of plastic drawers and Antonio opens the top drawer and removes from it an indigo snake about eighteen inches long, a hatchling, and hands it to me. Into the silence I proffer, he says, “Isn’t that cool?” For several reasons, some of which can be articulated, it is. I manage to say, “Yes.” The snake is, for one thing, a homunculus, a scale model of an adult. Some snakes have the cuteness in the young that characterizes mammalian young—large eyes, delicate body, undeveloped features. Not these. Full-on adult snake in miniature, a bold, strong, confident little purple thing. Second, it represents extinction that quite clearly is somehow making little ones of itself. It rocks my world. Antonio shows me two-year-olds, four-year-olds. We migrate to a breeding building. He shows me large indigos, one confiscated from a trailer in Ocala with no surrounding habitat for the game wardens to release it in. At a cage a gravid indigo is in her laying box with her head just out of its hole, watching the room.

When we approach, she does not draw into the hole. Antonio hands her to me. I get a vibe unlike any I’ve gotten so far. She is not anxious to be put down. Nor is she content to find herself against a warm body, to stabilize and sit tight as a constrictor may. Nor is she crawling to get out of a tree she somehow can’t get out of, the position taken by many snakes. She regards me, regards Antonio, and thinks at least this: Hmmm. I say to Antonio, “This is a thinking snake.” Antonio says, “Yes.” He has known me not an hour. He does not know that I am insane or not insane. He sees that I am right about this snake, because he knows this snake.

We return her to her cage. She reenters her laying box, as any snake would; she circles within it, as any snake would; and she extrudes her head and rests her chin again on the bottom edge of the hole in the box to resume observing the room, as any snake would not. A dog would do this, not a snake. If you pick up a dog and hold it, it seems to think, I don’t know why this is happening, exactly, but it is A-okay. That is why I told Antonio the snake was a thinking snake. It thought precisely that, pretty much.

All of my suppositions and impressions about indigos formed by the snake in 1964 that bit Mike Wilkerson after the play turned out to be not inaccurate. When Antonio handed me the snakes in the lab, fifty years later, I felt I already knew how they move and think. An indigo snake leaves a lasting impression.

Seeing Extinct Snakes Outdoors

To see the extinct outdoors is a bit harder than seeing them indoors. You have to go into the habitat that is now so famously lost, degraded, and fragmented: the longleaf pine forests and sandhills in Georgia and Florida. In the north of this range the snake makes what is called obligative use of gopher tortoise burrows, in the south nonobligative use, meaning the snake is not confined to burrows for its refugia, one of the favorite words in herpetology. In warmer months the indigo can range into low-lying areas—hardwood swamps, pine flatwoods. What has degraded, destroyed, fragmented these terrains is a hurricane of forces: logging when we had forests in the 1800s, fire suppression once the original forests were gone, agriculture large and small, urbanization, and pandemic silviculture (putting seven hundred trees on an acre where seventy once stood). Between these fragments of terrain are roads—an indigo is a huge target and has a lot of himself or herself to get across slick asphalt. To the lay eye, the snake wants some dry ground with some tortoises on it or near it. Usually a pine tree about. Some sand. Some peace.

Photo: Greg Dupree

Serpent Turf

A swamp at the Orianne Indigo Snake Preserve in Georgia.

I am turned over to Dirk Stevenson, the chief field wrangler for Orianne, who came down to the Okefenokee as a child from Illinois and was photographed with an alligator beside the family car, and his chase gene metastasized. He has caught, marked, and recaptured indigos at last count 418 times for Orianne (257 individual indigos), and he agrees to take me afield with an enthusiasm only a man with a metastasized chase gene can show: “I am excited. We shall herp as few grown have.” “I am sure looking forward to draping a 2 m Dry about your person.” (A “2 m Dry” is a six-foot-plus indigo, Drymarchon couperi. The herping tribe likes Latin and likes to use it, often in coded and satiric ways. “Harry Greene is very interested in where and when you filmed the horridus footage, if you are willing to share.”)

Stevenson takes me on a tour that includes a private tract of land under Orianne’s managing help and two conservation easements. It is May and I am told not to expect an indigo, because we are beyond the obligative-use period of the gopher tortoise burrow. I don’t expect to see one, because I am now convinced they are vestiges in a laboratory only. We see beautiful land, hill and dale of good longleaf pines, and dozens of marvelous golden-sand burrow aprons with no snake on them. Driving a jeep trail beside a fence line, we see a flash of something that looks metallic—I think it might be a bicycle fender—and as I realize it is a coachwhip, Stevenson has ratcheted the truck into park and we are out of it and I try to go through the fence where the snake is headed, into a pasture, where I think it will open up and run like a greyhound, and Stevenson with a limp that owes to a knee or a hip I’ve not asked about runs back down the fence line, behind us, I think to get through the fence better than I have, because I am hung in it, completely, and Stevenson comes limping back with the coachwhip coiled in one hand and offers it to me. Running this snake down is to my mind not unlike Will Smith’s running down the cephalopod or whatever it was that qualified him to be a Man in Black. Moreover, the coachwhip, which I had thought to be a biter, is in a happy docile set of loops about the size of a ladies’ handbag when Stevenson hands it to me. I begin to think maybe this guy knows what he is doing. If he can run that snake down—it’s the fastest there is, here—and charm it into a neat limp nine-inch coil, maybe he can drape a 2 m Drymarchon couperi about a person. The realm of possibility tilts.

At the conservation easements we join some other herpers, a term I use loosely and don’t like at all. We join people who want to walk around with Stevenson and maybe find an indigo. I begin to see a certain ethos among these people, who more loosely might be called conservation-inclined naturalists and scientists of one stripe or another. There is an ethos among them that a proper man should know what everything in the woods is. En route to a snake, if that is the target, he identifies the plants, the birds, the trees, the soil, the rocks.

Frankie Snow is a naturalist at South Georgia State College in Douglas who seems to know what everything is, and walks the woods in neat pressed jeans with a marvelously yellow magnolia walking stick and mystical-seeming wisdom. He is the definition of the man with a small chase gene delighted to find a snake in the bushes. (I am an amateur, ignorant of every plant and bird in the woods, stumbling on the rocks, after the snake. Stevenson is in the middle.)

With eyes out for indigo, Frankie Snow delivers a running commentary as we walk, pointing at plants. “Deerberry is a blueberry,” he says. “Gallberry is a holly.” He cocks an ear: “Bachman’s sparrow.” We pause, listen to the sparrow, resume. “That Isoetes there”—he points too vaguely for me—“is the rarest plant on-site.” I am dumbfounded, if that might mean foundered on one’s own dumbness. Suddenly Frankie Snow says something that means something to me: “We’ve counted nine individuals right here.”

“Nine individuals? Do you mean indigos?

“Yes.”

“Nine? Right here?”

“Yes.”

They would know it is nine individuals because each would have been marked with a microchip, called a PIT tag. Frankie Snow, with his beautiful yellow stick, his nice blue (non-camo) pants, his soft-spoken all-knowing of the ground and the air, is not jiving me. I begin to hyperventilate, just a bit, ready to stumble on the rocks.

No snake is seen.

Photo: Greg Dupree

Emerging from a gopher tortoise burrow.

An Indigo Blitz in South Florida

A doctoral student, Javan Bauder, invites a group of herpetologists to the Archbold Biological Station east of Arcadia, Florida, to participate in what is called an Indigo Blitz. The purpose will be to capture two specimens that are the right size for the last of Bauder’s federally approved radio implants. This will give him a total of two dozen snakes radioed up for his population-viability study, which is to constitute the fundament of his dissertation, a thing he hopes to be able to do. By my lights a dissertation is an improbable thing even before its execution is predicated on locating live extinct animals.

Archbold Biological Station is so out there, so intact and pristine-feeling and starlit and big, that you get a frontier-Florida feeling and want to call people and tell them you’re there. “And?” they’ll say. “And nothing—I’m here. It’s…” It will do no good to convey the weird sense of things, the pastures and the scrub feeling like Indians ought to still be on it, the small slate-shingled houses for the researchers that feel forties-made and that Archie Carr must have stayed in, if not Audubon or Bartram.

Stevenson and a field man named Andy Day who does population surveys for Orianne come in from a trip they made that day near the Everglades. They have a Florida king snake they found on rocks beside a canal; it coils on my left hand and we type e-mail together for two hours. A king snake is not a thinking snake, beyond what is necessary.

They have found something else. They saw some vultures working something on the edge of the road and Day said, “Let’s go see the indigo those vultures are eating,” and they stopped and saw that the vultures were indeed eating an indigo. It is a freshly dead extinct snake, the closest I’ve come yet. It is over seven feet long, and the carcass is so voluminous and mutilated and grisly it is hard to look at. A man could easily weep a little.

I go out with Bauder and his radio man Patrick Barnhart to find nine of his two dozen radioed snakes. We go initially into some very heavy palmetto cover about truck high. The first snake, Naja, is found, underground. It takes a good half hour to locate her. The second snake, Angelo, is also found underground. The process is to use a nondirectional antenna until a signal is secured, switch to a directional antenna, wade into this distressingly heavy cover toward the signal, lower the gain as the signal strengthens, and finally, by a series of signal-here, no-signal-there passes with the antenna at the ground, to determine, with reasonable conviction, that the snake is right here, under you. GPS coordinates and temperature of the air and the ground are all entered into a log and the data later plotted out, providing a tidy home-range overlay graphic for the particular snake on an aerial map. The indigos at Archbold have home ranges spanning from 59 to 1,360 acres, and you can see on the aerial map where they roam and forage. After Naja and Angelo we head for Rambo, snake number three, over in the southwest part of the compound.

On the way we are called to another group of hunters near where Rambo is. They have caught an indigo—in fact, Chris Jenkins has. I see my first one alive and not in a lab or zoo. It is adult, but not huge. We head for Rambo, get another phone call. The bastards have found another one, a hatchling. We go back and see it. Ass chapping. I see now the snake is extinct to me, not to others. I get it.

We arrive finally at Rambo turf and while Bauder and Barnhart are getting the gear out I head on out to where they tell me we are going. It’s a grassy road going down through a shallow creek; on the left of the road is a very improbable highway-grade guardrail. A barbed-wire fence is running along the road on the left, too, becoming one with the guardrail. Why a real guardrail would be on one side of a ranch jeep track on land that has not even been a ranch for a good while…and suddenly I am aware that the ground more or less under my feet is rumbling, a black rumbling moving and moving fast down this incline along this fence coming to this guardrail, and without seeing it well I am moving too, fast, with this damned indigo snake, no doubt about it, its black blurred presence now shearing under the barbed-wire fence to the left and heading for the creek, and I am too, and can’t get over the fence, and can’t get over the guardrail and the fence, and the snake gets in the creek, makes a hard left turn, goes up the creek for ten feet and into a copse of palmettos on the bank. This takes about five seconds. The palmetto rhizomes emerge from and go back into the bank like giant snakes themselves, a metropolis of thick rhizomes like elephant trunks in mud. The snake needs one hole, and these rhizomes provide fifty. I am hyperventilating a lot. Were I going to have a heart attack from excitation, I would have had one right there. We hunt the area for a bit, but we are fools to bother. Three of these extinct snakes a quarter mile from each other! The one we don’t get, mine! A highway-grade guardrail!

Rambo is located underground. Venus (she was caught in flagrante delicto with a male named Sigma on Christmas Day) is located aboveground, moving; we see only a foot-long section of her for a tenth of a second in a part in the grass she is porpoising through at a burning speed. We locate, all underground, CSC, Homer, Marge, Sigma, and late in the day the ninth snake, Betty Ford, so named because she crawled up into a Ford when she was initially captured.

Extinct to me has set in with some teeth. I want to see one of these snakes and catch it. Can it happen? I leave the radio team and go with Stevenson and Day in their truck back to camp. We are flying along when Day, sitting sideways facing the rider’s side of the truck in the little half-seat thingie of the Tacoma, says, in a serious tone I’d not heard from him, “Got one.” Stevenson slams on the brakes. I open my door and step out, thrown into the door as happens when you step out of moving cars, and begin running back to where Day must mean by saying “Got one” when he said “Got one.” The snake is on a patch of sand the size of one half of a Ping-Pong table. The other half of the Ping-Pong table is a patch of grass not more than six by four feet. The snake raises its head and looks at us coming, holds the look just a second, and then whips its head away toward the grass and goes. I land on the snake in the grass softly so as not to hurt it but can’t feel anything to pin. Day goes to the farther half of the patch and paws it in the same flat-palming way, covering the area with replacements of his hands and whole forearms, as a cat might. He has gone beyond where I saw the snake. I know I jumped right on the snake. I assume he will get it, and that he has gone where the snake was not because as a pro he knows something I do not. Extinct to me. Somehow a giant black snake the girth of a motorcycle tire and over six feet long has disappeared from an area the size of a Ping-Pong table, one half sand, the other Bahia grass not a foot high. About an hour later, after we issue all the postmortems we can issue, Stevenson says it went into a hole under the grass and that we could have dug it out but it would have taken an hour. I have seen three live indigos this day, aside from the two slow ones somebody else caught. The ones I have seen are the fastest and smartest snakes I have ever seen. But I have seen them. They are not extinct.

Back at our slate-and-linoleum research pad, like an old Florida lake house, the adult indigo Chris Jenkins captured that day before I failed to capture mine is “worked up”—that is, sexed, measured, weighed, and PIT tagged. The sexing involves inserting a stainless probe into the cloaca. In theory, the theory of the humans doing it, it does not hurt. When this snake gets his/her probe in, he/she bites Patrick Barnhart the radio man, who is holding the nonrelevant end, on the thumb. Unlike sturdy Mike Wilkerson, florid Patrick Barnhart does not flinch. He takes it as a scientist should. A small trickle of blood issues. When the probe is removed, the snake releases his grip on Barnhart’s thumb and has no more quarrel with it, or with anyone, just as the Jacksonville snake had no more quarrel once the security hazard was removed. The snake being probed at the blitz I believe just needed a bullet to bite. No one present knows it, but I am working on a hypothesis myself. If an indigo must bite a human, it will bite on the thumb.

We Finally Get Real

Stevenson takes me to some known ground in southeast Georgia, not in May but when it is supposed to happen. It happens. We come upon a slash pile with a burrow more or less into the side, or edge, of the slash pile. We are about twenty feet away yet and Stevenson points out an indigo on the slash pile, sunning. “There you go. Go get her.”

The snake is on this pile of logs and limbs, and she is facing, and not far from, a cliff of sorts in the pile of logging detritus that drops off sharply, and growing up this cliff are prodigious very thick blackberries. If she crawls just six inches she will be in heavy briars, inextricable. She can probably just enter the very slash pile where she is without moving anywhere. I don’t know why she has not already disappeared.

“No,” I tell Stevenson. “If you need that snake, you better get her yourself.”

“You sure?” It has been a year at least that he has been trying to drape a Dry about my person, and this disappoints him. I think the disappointment of my losing this snake for him will be greater, and I see no way, given what I have seen, that it can be captured by me.

Stevenson clops as ungainly as a man can clop across the face of this pile of trash, moving logs under the very snake, which continues not to alert, so that I am beginning to think this is surely a dead snake, and he finally gets there and picks her up, and looks at her face closely, and says, “Yep, just waking up.” Her name is Stacey. This is her third or fourth recapture. She is doing well. I’m a little miffed. These Georgia snakes is way yonder different from them Florida snakes. The next one is mine.

But it is not next. I see one caught by the half party that goes the way Stevenson and I don’t go one day, a big female that one of the two women on the trip who has never held a snake at all wants to hold all day until its release. On that trip Stevenson and I hunt a burrow, lying down to look for tracks, as one does, a few feet from a diamondback, which we don’t see but which another person finds, calling us back to the hole to show us how astute we are. I survey hundreds of burrows with Andy Day, going to hundreds of burrows via GPS waypoint, without seeing a snake, or even a tortoise. But I must say: Once you get a taste for the longleaf pine and wiregrass, this may be the best futility on earth. I think this is the serenity I saw in Frankie Snow.

Photo: Greg Dupree

Longleaf pines line a road.

And one day, I do not now know where, Stevenson and I put in a long day, and at the end of the day, no snake except maybe a diamondback he saw but I of course did not. We wander off a bit done-for-the-dayish onto, I think, some property adjacent to where we were actually supposed to be. It is not grand woods. Planted pines. A couple of burrows. Stevenson calls me from the burrow I’m scoping to the one he’s at. He’s about ten feet from it. I come up, can see the apron, stop. Close enough to see the area, not too close. “I might be mistaken,” he says, “but I think there’s a Drymarchon couperi in the Vaccinium.” There is something in his attitude that tells me this is not just pranking. There is nothing on the ground around this apron other than a low reddish bush that looks like thinning hair on a redheaded aging man. I can see the scalp through it. I get closer. There is nothing in the bush, but Stevenson is standing there like a bird dog on point that has not lifted a leg or gone rigid in the tail. I get between the burrow and the bush, nearly over it, and where there was nothing in this thin bush there is a six-foot bluish snake nervously calculating relocation. I check the broader area: nothing but some thin pine straw for thirty yards, no holes, no palmettos, no briars, no Ping-Pong tables of innocent grass. There is hardly anything on the ground that would allow for traction. This snake has only one option.

I put my foot right in the mouth of the burrow and kneel down on one knee. This is called blocking the plate. I can get up just in case he does try to run. Even if he does, he is going to slip on the straw. Even if he is as fast as the Florida snakes and does not slip on the straw, he cannot outrun me for thirty yards. He knows all this and I know it. I have a goat-herding stick I brought home with some difficulty from Kenya with me. It is thin and nicely finished and light and strong, and with it I touch the Vaccinium gently just to supply a joule of nervous giddyup to the situation. It’s a herding stick after all. The snake advances a foot or so, his head clear of the red bush, and looks at the expanse of flat ground with the straw on it. He advances yet, still straight, not turning to the hole but going around it, more or less, until I put the stick on the ground ahead of him, and he goes ahead and turns, calmly, inevitably, for the hole, and as he passes my outside foot and comes to my knee I pick him up with my left hand and put down the stick in my right and get that hand on him too for support, and, after looking fifty years for my extinct snake, it has crawled right to me. And I see that I have a style: I will not rush an indigo snake if I do not have to. You do not knock the door down and handcuff a reasonable man. You ask him to come into the station, and he will.

Can a Snake Be Saved?

I witnessed a man in a physical-therapy clinic, told by the cute young women trainers having him do light-barbell curls that they wanted him to get stronger, ask the women, without guile or menace, “Can an eighty-year-old man get stronger?”

I would like to ask, with the same want of cynicism, can a snake be saved? Or is it the case that an effort to save a snake would be the very most hopeless effort in the entire lost world, the lostest of lost causes that have left us our mostly ruined planet? Had I not been haunted for fifty years by this snake, I would not ask if it can be saved.

What if the proposition were put to us that we could save at least our part of the world if we could save this giant purple friendly snake? Would that be any less absurd than suggesting we could save the world by saving the elephant, or the tiger? As it happens, Orianne was initially funded by the same party who funded Panthera, the foundation trying to save the big cats. The creation myth for Orianne (a myth that happens to be true) goes that Tom Kaplan’s (of Panthera) daughter Orianne said, more or less, Daddy, if you’re saving the tiger, you ought to save this great purple friendly snake, too, and Daddy decided to try.

Proposing saving the elephant or the tiger in order to save the world might be a shade less preposterous than proposing saving a snake in order to save the world, by which I mean that a few more people might get in the game to save the elephant than would get in the game to save a snake. It happens, though, that the game to save the elephant is not going well. It has brought us, we are told, to the slaughter of twenty-five thousand of them a year for their two big front teeth. That does not bode well—the unforgetting, majestic, circus-employable, Dumbo-inspiring giant who mourns its dead and whose prehensile monstrous wiry-haired trunk even children want to touch we cannot save to save our lives. How would we purport to save instead a snake, in a world of people who fall into three camps vis-à-vis snakes: the only good snake is a dead snake, a snake is all right if it stays over there, and snake nuts?

It’s a fair question, and only a snake nut would pose it. But as Randy Newman said of Lester Maddox, this snake is our snake. This is our elephant.