Arts & Culture

The Curious and Twisty Love Story Between New Orleans and Disney

The fascinating, decades-long dalliance between the Crescent City and the Disney version of it, starring a cartoon princess, Creole chefs, mechanical tiki birds, and the world’s most meticulously researched flume ride

Illustration: MARK HARRIS

In 1959, Mayor Victor Schiro (right) proclaimed Walt Disney an honorary citizen of New Orleans; in turn, in 1966 Disney invited Schiro to help dedicate New Orleans Square at Disneyland.

In the spring of 2006, in the midst of a primary election for mayor of New Orleans, a candidate named Kimberly Williamson Butler posted a photo on her website. At first glance, it was ordinary enough campaign stuff: Butler smiling, her arms crossed authoritatively in front of a picture-perfect New Orleans background of quaint French Quarter buildings and wrought iron balconies. On closer examination, though, there was something off. Over the candidate’s left shoulder sat a trash can that didn’t look like any trash can found on the streets of New Orleans. In fact, as observers quickly noted, it looked very much like the trash cans found at another popular tourist destination, 1,900 miles away. The campaign quickly scrubbed the can from the photo, but by that time the mouse was out of the bag: The snapshot had not been taken in New Orleans at all, but in “New Orleans Square,” at Disneyland in California. Butler was about to become a source of amusement around the world (but decidedly not the mayor of the city of New Orleans).

Almost twenty years later, I found myself standing at about the same spot as Butler had, squinting at the streetscape in front of me and sympathizing with her, or whatever staffer had committed that fatal photographic blunder. Trash cans notwithstanding, Disneyland’s New Orleans Square really does look like New Orleans. Or rather, it looks like a very specific piece of New Orleans that tourists are most likely to visit; the street signs identify it as the corner of Royal Street and Orleans Street, almost dead center of the French Quarter. True, the magnolia tree on my right felt 20 percent too big, casting everything into a surreal scale. (Some say it was planted to screen parkgoers from the disorienting sight of the Matterhorn ride’s snowy peaks towering above Royal Street.) The Mardi Gras mask suspended over the street might have been a little too on the nose, even for the Quarter. And, of course everything was much cleaner and shinier. But here was a row of Creole town houses, with their bright colored shutters, the flickering gas lamps, the balconies hung with purple and gold beads. On one sat a painter’s easel; on another, jazz instruments.

The resemblance was as uncanny now as it must have been when New Orleans Square first opened, in 1966. This is not just the product of Disney’s famously detailed Imagineering, but rather a long and tightly knotted history between the two places: Disneyland may look like New Orleans, but New Orleans also looks like Disneyland—in no small part because it’s Disney that has taught generations of Americans, including New Orleanians, what it is that New Orleans should look like.

My journey to New Orleans Square began a year earlier, when I drove a mile or so from my home to a corner not of Orleans Street, but of Orleans Avenue, where the legendary Dooky Chase’s Restaurant sits in the real New Orleans. For seventy years, chef Leah Chase ran Dooky Chase’s, turning a neighborhood sandwich shop into a center of the civil rights movement, a genteel gathering place for Black diners when many other restaurants still barred them, and a standard-bearer for Black Creole cuisine. Since Leah’s death in 2019, her sprawling family, including her daughter Stella and granddaughter Eve Marie Haydel, have nurtured the restaurant’s legacy.

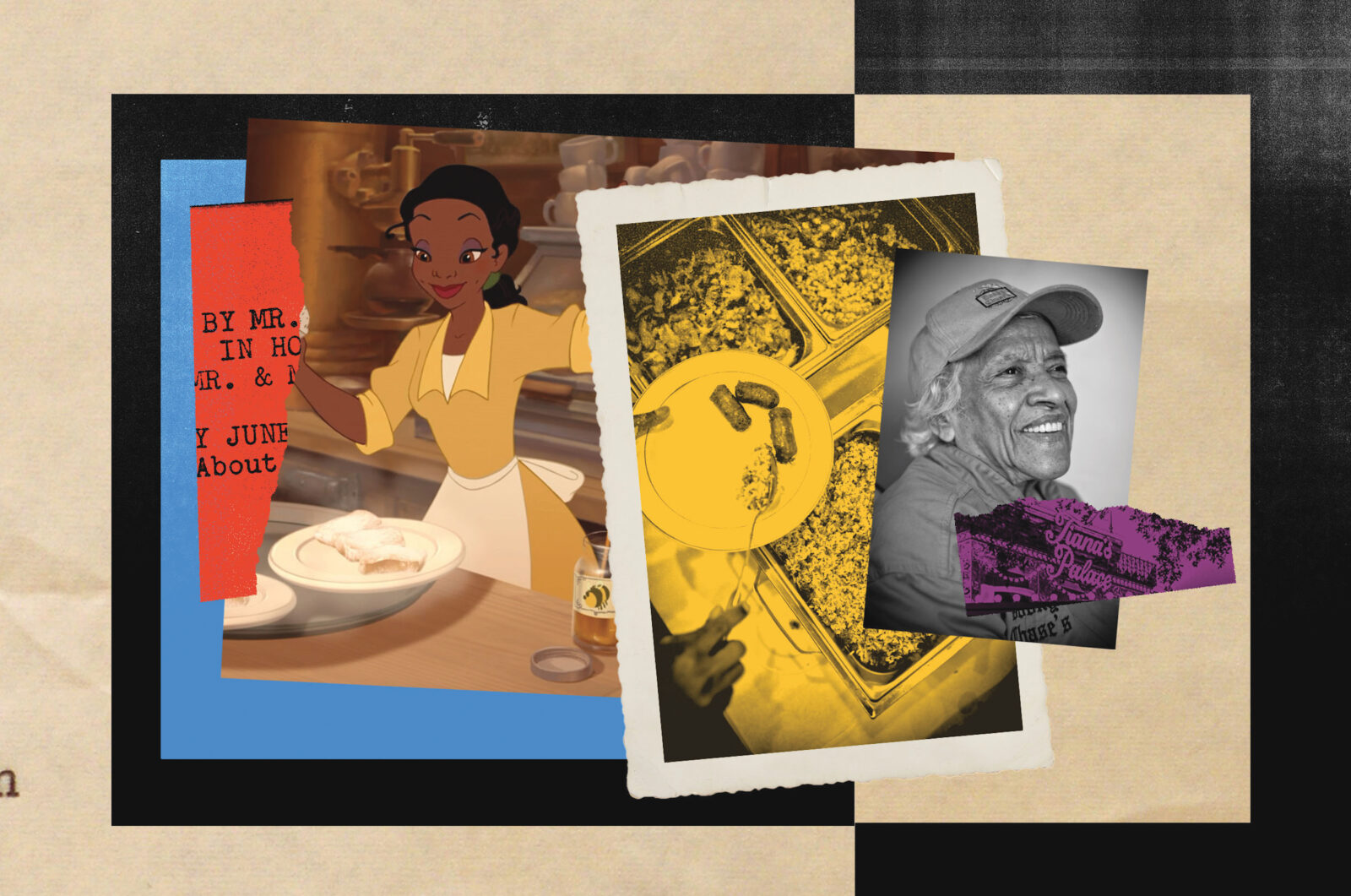

In addition to her many other accomplishments, Leah Chase was, according to Disney lore, the inspiration for Tiana, the lead character in the 2009 film The Princess and the Frog. At Dooky Chase’s that evening, a media event heralded a new ride based on the film that was set to open at Disney’s two American theme parks. It had been a long time coming for fans of The Princess and the Frog, which features the first Black princess in Disney’s history. After years of rumors, the attraction, named Tiana’s Bayou Adventure, had finally been given the go-ahead in June 2020, during the summer of protests for the Black Lives Matter movement. In a fairy-tale twist, it would be replacing Splash Mountain, the iconic Disney ride originally based on Song of the South, a film so notorious for its racial insensitivity that Disney has refrained from releasing it on home video or streaming services for nearly fifty years.

Outside the restaurant, some thirty media members—from newspaper reporters to Instagram influencers—milled around, excitedly shooting selfies and recording videos. They had already spent the day touring a swamp and visiting the nonprofit arts center YAYA, an alumna of which had contributed paintings that Disney used as source material for the new ride. Courtney Quinn, known on social media as “Color Me Courtney,” posed in front of the Dooky Chase’s sign wearing a jacket with “Almost There”—a song title from Princess— stitched in script on the back. Quinn collaborated with Disney on a Tiana fashion line and has participated in celebrations known as #TianaTuesday, in which fans share outfits in homage to the princess. “It’s huge,” she said about Tiana’s impact. “Just a huge moment in representation.”

Tiana herself, or a version of her, waited in the dining room, wearing a green ball gown, elbow-length evening gloves, and a tiara. She stood, surrounded by the restaurant’s collection of African American art, near a baby grand piano, played by the great New Orleans pianist Rickie Monie. When my turn came to take a photo with her, a character handler deftly lifted the mint julep from my hands and placed it on a table, out of frame. How was she enjoying New Orleans? I asked Tiana, awkwardly.

“How can I not be happy, here in my hometown, Sugar Plum?” she cooed, in a voice more Savannah than Ninth Ward, but otherwise convincing.

As we dined on poached shrimp, Creole gumbo, and grilled redfish, a Disney executive introduced Terence Blanchard, who had played trumpet for the alligator character Louis in the original film and who, the day before, had been in Baltimore, receiving a Peabody Award. Stella Chase spoke, as did Carmen Smith, an Imagineer on the team that developed Tiana’s Bayou Adventure. Smith’s voice was mellifluous, immediately soothing: “This is a bedtime story,” she said. “It’s a bedtime story about hope.”

I was sitting with Gavin Doyle, who began blogging about Disneyland and Walt Disney World in Orlando when he was thirteen years old and founded MickeyVisit.com, a popular website of park news and tips. Doyle has teams of reporters who walk the parks regularly, noting even the smallest scoops. Minor menu changes can cause a huge stir, he told me; that week, Disney World had erected a new sign, and it had taken exactly eighteen minutes for the tidbit to be posted on social media. Given that level of scrutiny, it was easy to understand the fuss over a major new ride—particularly one replacing a beloved tentpole attraction. After the ride opened at both Orlando’s Magic Kingdom and Disneyland Park last year, I sat through an hour-and-ten-minute YouTube video comparing Tiana’s Bayou Adventure with Splash Mountain in forensic detail, followed by nearly five hundred comments.

Of course, Disney faced the added pressure of telling a Black story, something the company has not always done smoothly. If there was one message of this press trip, and all the publicity surrounding Tiana’s Bayou Adventure, it was that this time Disney had done its homework. A dozen Imagineers had made multiple trips to New Orleans. They had spent hours in archives and in the streets, sifting through records in a quest for absolute accuracy. Locals had been solicited to create elements: PJ Morton composed and recorded an original song, and a third-generation master blacksmith from the Seventh Ward named Darryl Reeves fabricated an iron weathervane to sit atop the ride’s loading shelter. Into the attraction would be piped the smell of freshly cooked beignets.

Illustration: MARK HARRIS

New Orleans chef Leah Chase is said to have inspired the character of Tiana in The Princess and the Frog.

The next day, we visited the Historic New Orleans Collection for more presentations. We perused a gallery of artifacts that had especially stirred the Imagineers: a Mardi Gras Indian costume; a breastplate worn by the king of Carnival in 1893. The docent showing us around, it turned out, had worked at a Disney park himself. He waved exaggeratedly, which the crowd understood to mean that he had suited up as one of the characters wandering around the park—or, in unofficial parlance, had been a “friend of ” a character. Given his height, it was generally agreed he’d played Goofy, though perhaps Baloo the bear.

The team’s fixation on accuracy was admirable—and the desire to show it off understandable—but it still felt slightly weird: Isn’t Disney in the business of inventing reality? “You need a team that understands why,” Carmen Smith explained. “We need them to feel confident in their designs.”

All of it spoke to Disney’s unique challenge of balancing authenticity and fantasy, fun and social responsibility, nostalgia and the need to evolve. Well, not quite unique: As it happens, these precise dilemmas have long faced New Orleans, too. In fact, locals use a particular term when the city tips too far toward make-believe at the expense of the living city: They call it Disneyfication.

The love affair between Disney and New Orleans begins with Walt Disney himself. Archival correspondence dates his first visit to 1937. Entranced, he returned throughout the 1940s, including to ring in 1946 at the Sugar Bowl, and later that year during promotion for Song of the South. It was on this trip, or one soon after, according to Walt Disney Archives director Becky Cline, that Disney stopped into a Royal Street curio shop and discovered a mechanical singing bird manufactured around the turn of the century by Bontems of Paris. Such automatons fascinated Disney, and he had this one (along with another, a gift from someone in France) sent to his team in California to be disassembled and studied. Its progeny—from the founding fathers in the Hall of Presidents to the droids in Star Wars: Galaxy’s Edge—would become one of the signature technologies, trademarked Audio-Animatronics, of the new immersive amusement park Disney was beginning to envision.

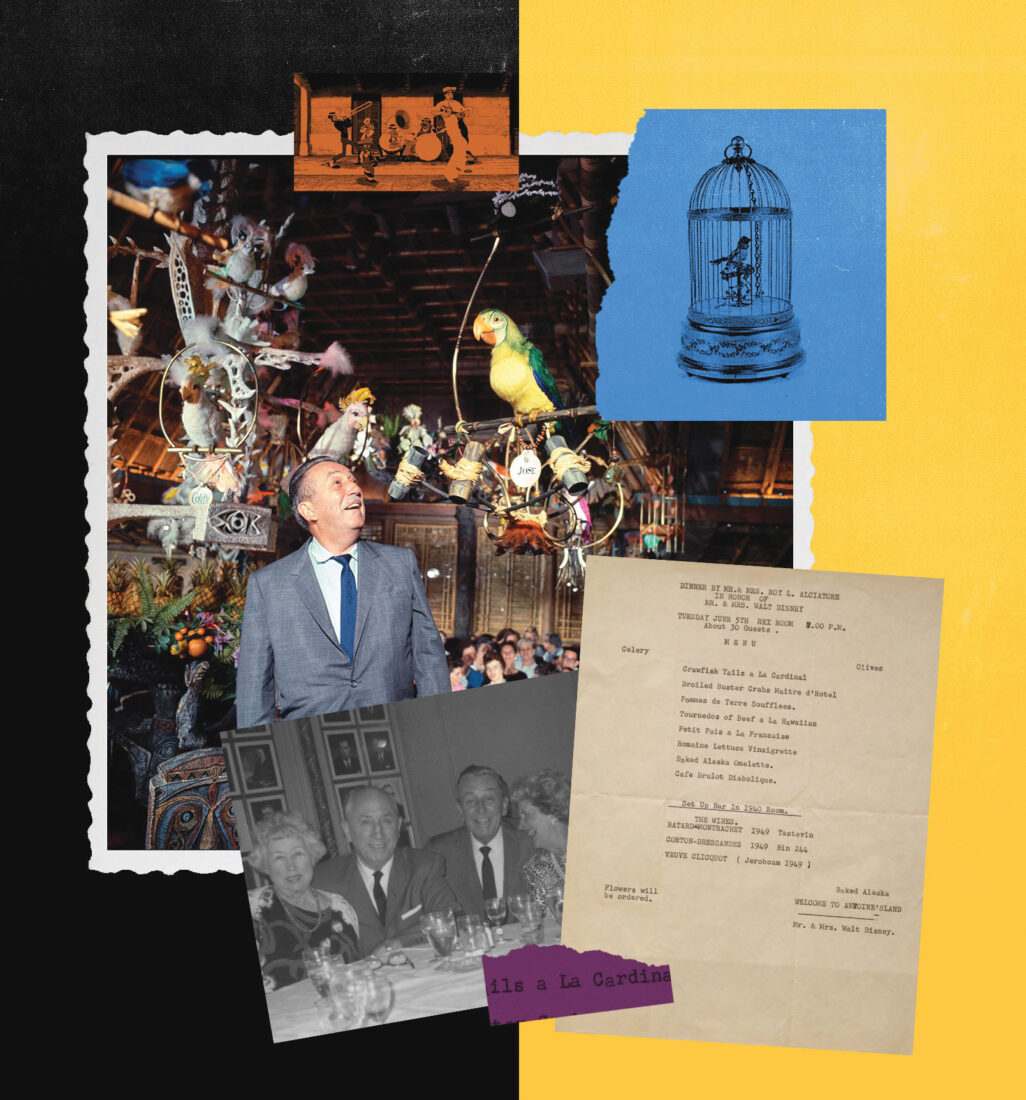

Disney also became a regular at Antoine’s Restaurant. The French Creole institution was already 116 years old when it hosted a 1956 dinner for thirty or so people in Mr. and Mrs. Walt Disney’s honor. It was held in the famous Rex Room, and the menu included crawfish tails à la cardinal; soufflé potatoes; tournedos of beef “à la Hawaiian,” and Baked Alaska (thus covering both soon-to-be states), all washed down with a jeroboam of Veuve Clicquot, among other beverages. At the bottom of the typewritten bill of fare somebody attempted a play on the name Disneyland: WELCOME TO ANTOINE’SLAND.

Illustration: MARK HARRIS

During his visits to New Orleans, Disney often dined at Antoine’s Restaurant. On one trip, he discovered a mechanical singing bird in a French Quarter curio shop that would later inform such iconic Disney attractions as the Enchanted Tiki Room.

It’s not hard to see why New Orleans appealed to Disney. To this day, there are few cities in the United States that feel so much like stepping outside the United States. Disney clearly appreciated this otherness and its appeal: Disneyland would be anchored by Main Street, U.S.A., a thoroughfare reminiscent of his idyllic, small-town childhood in Marceline, Missouri. That would be Disney’s vision of America; New Orleans Square would be something else.

For all that, it would take eleven years after Disneyland’s 1955 opening for New Orleans Square to make its debut—the last major addition to the park that Disney oversaw before his death. That didn’t mean the Crescent City was absent from the park’s first decade. From the beginning, Frontierland, which invoked the Wild West, included New Orleans Street, where Don DeFore’s Silver Banjo restaurant sold barbecue (much like the accent of the Tiana at Dooky Chase’s, Disney has often conflated South Louisiana with the South in general, which most New Orleanians will tell you begins north of the city).

A decade before Preservation Hall opened in New Orleans, Firehouse Five Plus Two may have been the most famous traditional jazz band in America. Its members were Disney employees (all white men) who happened to play on the side, and they frequently gigged at the park. The offspring of Bontems’ mechanical bird popped up everywhere, perhaps most spectacularly in Walt Disney’s Enchanted Tiki Room, which is still a genuinely enchanted experience, with its thrilling chatter of analog beaks.

When New Orleans Square finally did open in July 1966, Disney invited the mayor of real New Orleans, Victor Schiro, to the ceremony. He and Walt joked about switching jobs for the day and about how the price tag for the new “land” ($18 million) exceeded that of the entire Louisiana Purchase ($15 million). Disney also remarked, proudly, that New Orleans Square was cleaner than the original. No doubt this was true.

The points of connection would continue. The North Shore of Lake Pontchartrain, a short drive from downtown New Orleans, was one of several places considered for Disney’s next theme park. (Local legend has it that the corruption of Louisiana’s politicians, and their demands for kickbacks, scuttled the deal and sent Disney packing for Orlando.) New Orleans Square would eventually contain two of Disneyland’s marquee attractions: Pirates of the Caribbean and the Haunted Mansion. To walk through the real French Quarter today, dodging ghost tours and buskers dressed as pirates, is to understand how loudly the tropes of these rides echoed back to New Orleans and how deeply they have become stitched into the city’s own iconography.

If Disneyland introduced Americans to how New Orleans looks, it also gave them a hint of how it tastes. Located inside the Pirates of the Caribbean attraction, Blue Bayou Restaurant is set amid an illusion of an antebellum mansion, past which the ride’s boats float on a fake river. In a very New Orleans way, diners and riders become actors in the others’ entertainment. When Blue Bayou opened, in 1967, its menu included nods to French Creole fare, including Crabmeat Saint Pierre, as well as such further afield dishes as Le Pâte Boulette de Viande (spaghetti in meat sauce) and, famously, the Monte Cristo. That sandwich, though deep-fried and vaguely French-seeming, is about as New Orleans as Tiana’s Healthy Gumbo, a recipe for which appeared on a Disney Facebook page in 2016. The “gumbo” featured kale and quinoa (but no roux), and commenters roasted the recipe across social media and beyond, achieving the seemingly impossible feat of unifying Louisianans on a matter of gumbo preparation. Disney magic, indeed.

I am pleased to report that there was no quinoa in the 7 Greens Gumbo at Tiana’s Palace, the new Disneyland restaurant adjacent to New Orleans Square and Tiana’s Bayou Adventure. Have I had better versions of Leah Chase’s famous gumbo z’herbes, including ones that didn’t mysteriously include sweet potatoes? Obviously. Same with the Mickey-shaped beignets available nearby, and the crab cakes and rémoulade I ordered at Blue Bayou. But have I also had worse, including in New Orleans restaurants I would defend as decent introductions to the city’s cuisine? I have.

Finally, it was time for the ride itself. From New Orleans Square, I walked over to Bayou Country. If Disney does nothing else but get it through visitors’ heads that New Orleans and the swamps of Cajun country are two separate things, it will have done the region a great service.

By this time, I had spent a year thinking about and hearing about this ride and the vast effort that had gone into its conception and execution. As soon as my log flume lurched forward, all of that left my head completely. I have a vague sense of there being a story—something about Tiana and Louis searching the bayou for musicians to play a Mardi Gras party. I remember a part where we were supposed to have been shrunk down to the size of a frog, another where we turned the corner to a dazzling scene of the New Orleans riverside, and in between, a long, terrifying climb through streaming light toward the ride’s signature fifty-two-foot drop. I remember remembering that I am a total wimp when it comes to amusement park rides.

Did any of it matter? I wondered as I disembarked, soaked, exhilarated, and shaking a bit. Had all those hours of research by the Imagineers been for naught? “It’s all in there,” Carmen Smith said in her hypnotic voice when I asked her the next day. “You’ll see it more each time you take the ride.”

That may overestimate my courage. But two sights do stick with me from that day, both occurring outside Tiana’s Bayou Adventure itself. A few weeks earlier, on Election Day, I had taken my daughters to lunch at Dooky Chase’s for the first time, thinking it an appropriate destination for a day when the nation’s first female Black presidential candidate for a major party was on the ballot. Stella Chase was working the floor, stopping by each table to chat and make sure everything was okay. At Tiana’s Palace, I watched as a Tiana character did the same, including at a table at which Stella herself, there for the ride’s grand opening, sat with her family.

The other sight was the stacks of Leah Chase cookbooks and Dooky Chase’s spice mixes for sale in the gift shops at New Orleans Square and Bayou Country—some of the very few non-Disney items to be found among the infinite merchandise offerings throughout the park. Frankly, the connection between Tiana and Leah had always seemed a bit thin to me, with little to connect the two besides career and, of course, race. But this was authenticity and representation with dollar signs to back them up.

It’s worth saying that it’s a problem when a city acts as though it is a theme park; ask anyone who has ever driven in the Quarter, dodging Hurricane-carrying tourists who seem to believe they are in some kind of magic kingdom. Likewise, it’s also a problem when we start to believe that a theme park can provide what a city does: Cities are messy, unpredictable, and sometimes scary—but also surprising, enlightening, and fun in ways no theme park can ever be.

Yes, you may meet Tiana at New Orleans Square, but only in New Orleans will you encounter a character like Kimberly Williamson Butler, whose notoriety began before her infamous photographic faux pas. Several years earlier, she was elected Clerk of Criminal District Court and immediately attracted attention for lavishly redecorating her office, most notably with $2,459 curtains. After Hurricane Katrina, she briefly became a fugitive rather than comply with a court order involving funds to clean up the courthouse’s flooded evidence room. When she reappeared at city hall, accompanied by her pastor, it was to make an announcement: “You know what? I don’t think I’m the right person to be clerk of court,” she said. “I think I’m the right person to be mayor.” The rest is history. And that’s what you call a wild ride.