Sporting South

The Legend of Black Gold

An unforgettable Indian horse that gave it all—and more

Illustration: Jason Holley

At the fair grounds in New Orleans, where the fabled Stewball ran, two solitary markers rise in the infield down the homestretch right beside the sixteenth pole. Beneath one lies the dazzling stallion Black Gold, the “Indian Horse” who ran to glory in the 1924 Kentucky Derby, and whose owner, Rosa Magnet Hoots, was a full-blooded Oklahoma Osage. Beneath the other lies Pan Zareta, a brilliant Texas filly who never lost a race against Black Gold’s mother.

It is a saga reaching back a solid century, as poignant as any in horse racing history.

When I was a boy, my parents would take me to New Orleans during the winter season at the Fair Grounds. We’d go from Mobile by train, on the old Hummingbird of the Louisville & Nashville line, breakfasting in the dining car, with its steam-fogged windows, linen-clothed tables, heavy railroad silverware, and white-jacketed waiters serving up hot pancakes and syrup. We always stayed at the Hotel Monteleone on Royal Street, with its magical Carousel Lounge where the big circular bar still turns ever so slowly on machinery from the 1890s. My father would let me sit beside him and enjoy the ride, sipping Coke or ginger ale through a straw — despite the fact that the legal drinking age in New Orleans at that time was approximately eleven.

Out at the racetrack it was always cold. In fact, New Orleans can be the coldest place on earth when a Texas blue norther combines with the thick Delta moisture to chill you to the bone. While my mother and the other wives went shopping, I would sit in the bleachers with my father and his friends in their overcoats and soft wool scarves and felt hats, watching the races through binoculars. Sometimes my dad or one of the others would even place a bet for me. I remember noticing the two small marble tombstones in the infield and asking about them, but nobody in our crowd knew anything about them. Once we asked some other people in the stands, but they didn’t know either. It was just “some horses,” they said.

Two decades passed before I learned the story. By then I was a young reporter at the Washington Star, and one of the men working the night shift was John Schultz, a gentle and erudite copy editor from Baltimore who had graduated from the Columbia School of Journalism and who, in whatever he claimed as spare time, was an inveterate railbird, handicapping horses around the East Coast tracks. When he found out I was from Mobile, he asked if I had ever been to the Fair Grounds and whether I remembered the little gravestone in the infield. I told him that there were actually two monuments, which surprised him, and that they had always been a mystery to me.

That night he told the story of the legend of Black Gold, a small, spindly horse of dubious lineage, with the heart of a Seabiscuit and the courage of a Man o’ War. It is a tale of poverty-to-riches-to-triumph, as well as one of malfeasance and indifference — even cruelty. In fact, it is the story of two horses, of how they lived and how they ran, and how they died and came to be buried side by side at a New Orleans racetrack.

In 1907, what is now the state of Oklahoma still appeared on United States maps as “Indian Territory,” home of the once mighty Great Plains tribes as well as the so-called civilized Indians — Creeks, Choctaws, Chickasaws, Cherokees, and Seminoles, who roamed the American South before Andrew Jackson banished them across the Mississippi along what came to be known as the Trail of Tears. There, amid droughts, blizzards, and tumbleweeds the size of buckboards that spun across the windy plains, these Native Americans scratched out a living from the soil, or sold trinkets from the sides of the road until, in 1890, the federal government moved them onto reservations and opened the rest of the state to settlers.

One of these settlers was a hardheaded Irishman named Alfred W. Hoots, who knew good horseflesh when he saw it, and always seemed to have something to prove. In 1907, several things happened to affect the fortunes — or lack of same — of Alfred Hoots. First, Oklahoma began to produce astonishing amounts of crude oil, then much in demand by the U.S. Navy. Second, on November 16 of that year, President Theodore Roosevelt, the Navy’s self-styled patron saint, signed legislation making Oklahoma the forty-sixth state in the Union. Third, also in 1907, a colt was born on an Oklahoma farm, a filly with the eye-catching name of Useeit.

Useeit’s pedigree was dubious at best. Her known lineage went back to the 1860s, and though it has since been questioned, it was not at the time. That is important because the rules require that horses in sanctioned Thoroughbred racing be registered as such, which, as one might expect, makes them a breed apart.

Since the breed’s inception in the late 1700s, all true Thoroughbreds can directly trace their lineage to one of just three fleet-footed Arabian stallions that were named for their owners: the Darley Arabian, the Byerly Turk, and the Godolphin Arabian from Tunisia, who is probably the most famous. These lean, swift runners were brought to England from North Africa and the Middle East to be bred to sturdy British mares, resulting in the spectacular animals one sees on racecourses today: long, strong legs and necks, wide muscular shoulders, heavily muscled thighs and quarters. But their most important characteristics are the stamina and athleticism that it takes to carry the weight of a man (and more recently, a woman) on their backs at breakneck speeds near 40 mph around an oval racetrack a mile or more long. There are faster sprinters to be sure; a quarter horse, for instance, can outrun a Thoroughbred any day, but only for a quarter of a mile — which is somewhat like the difference between a drag race and the Indianapolis 500.

Suspicious pedigree or not, however, Useeit must have been a thrilling sight to behold when Alfred Hoots first encountered her at the Fair Grounds racetrack in 1909. As a two-year-old juvenile, she had everything he believed it would take to become a champion, and to prove his point he made a trade for her with eighty acres of the hardscrabble Tulsa farmland where he and his Osage wife, Rosa, eked out a living raising cows. Thus Hoots not only achieved every Irishman’s dream of owning a racehorse, but it turned out he had a damn good notion of what it took to make one, since during the next eight years Useeit won thirty-four of one hundred and twenty-two races on the Southwest “leaky roof” circuits, an impressive record by any standard.

Problem was, like so many mares, she could tear up the track for about three-quarters of a mile but then ran out of steam, which simply wouldn’t do for the longer distances. Among her greatest competitors during those times was the venerated Pan Zareta, who won nearly half of her one hundred and fifty-one races, and whom Useeit never managed to best.

True to the deathbed promise she had made, the widow Hoots sought out the stallion that her husband had envisioned to produce a champion

Hoots, however, convinced himself, and insisted to anyone who would listen, that if Useeit could be bred to a stallion of uncommon endurance, the resulting progeny would, of all things, win the Kentucky Derby, which was then, as now, the most prestigious horse race in the world. But a dilemma kept Hoots from proving it: First, after giving foal, a racing mare is usually no longer a viable candidate on the track; second, Hoots didn’t have the money to pay for a stud fee anyway — at least not for the horse to which he wanted Useeit bred.

Hoots tried to solve part of the problem himself in 1916 when, perpetually short on cash, he entered Useeit in a claiming race in Juarez, Mexico. Under the rules of a claiming race there is no entry fee, but a price is put upon the horse, and when the race is over, anyone who pays that price can buy the horse. Hoots thought he had the bet covered because of an unspoken rule among horsemen that when an owner enters his only horse, no one will claim it — no matter what the price. But as bad luck (and bad manners) would have it, someone did. Hoots solved that problem by brandishing a shotgun and refusing to hand Useeit over — with the predictable result that both Hoots and horse were banned for life from the racing circuit.

In Hoots’ case that wasn’t very long because the following year he found himself on his deathbed, where he extracted a promise from wife Rosa that she would try her best to come up with the money to breed Useeit to the spectacular Kentucky stud Black Toney, known for his ability to finish what he started — namely a mile-and-a-quarter-long horse race, which also happened to be the running distance of the Kentucky Derby.

For two years after Hoots’ death in 1917, the banished Useeit languished in the horse pasture until, in 1919, fortune smiled on Rosa Hoots. It arrived in the form of a sho’ nuf’ Oklahoma gusher of an oil well on some grazing land Hoots had leased from the Osage Nation before he died.

Coincidentally, the year after Al Hoots passed away, and the year before his oil was discovered, the magnificent Pan Zareta also died. Her pedigree was no less suspect than Useeit’s, but between the two they had ridden roughshod over most of their male competition in those early years of the twentieth century. Unlike Useeit, who usually raced in the Southwest, Pan Zareta (or “Panzy,” as she was fondly known — she was named after the mayor of Juarez’s daughter) heard the starting gun from Texas to Kentucky, New York, Canada, and points in between. If you leave out the cynical handicappers, fillies have always occupied a special place in the hearts of racing fans, and Panzy was no exception: Whenever people heard she was racing, they came from miles away just to get a look. In 1917 she took the Oaklawn Stakes, beating the 1914 Kentucky Derby winner Old Rosebud. Although Panzy won few of the major events, mainly because she wasn’t entered, during her exceptional six-year career she took more races than any other mare then on record, earning more than $800,000 in today’s dollars.

After seven years of racing, Panzy’s owners decided to retire her for breeding, but when it was discovered she could not foal, they sent her back to New Orleans to train for upcoming Fair Grounds events. There, she contracted pneumonia and died on Christmas Day, 1918, and because she was so beloved by the fans, she became the first horse to be buried in the Fair Grounds infield, an honor that was bestowed only once more.

True to the deathbed promise she had made, with her oil money the widow Hoots sought out the stallion that her husband had envisioned to produce a champion. In 1920 Useeit was shipped off to Lexington, Kentucky, to meet Black Toney, a descendant of the immortal British racehorse Eclipse, and the premier stud at Colonel E. R. Bradley’s Idle Hour Farm. The resulting colt, born in 1921, was named Black Gold, an Indian expression for the oil that was now making some Oklahoma Native Americans wealthy.

As trainer for Black Gold, Rosa retained an employee on her farm named Hanley Webb, who had also trained Useeit, and who has been described as “old school,” which can mean anything from no-nonsense to hard-hearted. But whatever Webb did with the new colt as a yearling, it definitely showed up in his juvenile year, when he won the Bashford Manor Stakes at Churchill Downs, placed second in both the Cincinnati Stakes and the Tobacco Stakes in Northern Kentucky, and placed third in the Breeders’ Futurity Stakes at Lexington.

From the beginning, Black Gold had as his jockey a New Orleans Irishman named John D. “Jaydee” Mooney, who was so taken with Black Gold’s personality and spirit that he often made the sacrifice of declining to ride other horses. Much to his credit, Black Gold wasn’t quirky or finicky like a lot of racing animals, and showed a willingness to run and a determination to win that endeared him to fans and handlers alike. Though many critics derided the sleek little jet-black stallion as being undersized, his record in 1923 made him a likely contender in the much-touted Kentucky Derby. Then, on January 8, to the fans’ delight, as a three-year-old Black Gold started the New Year with a bang by winning the Louisiana Stakes — his first race in the big time — by six lengths and in a driving rain, too, confirming himself as a first-rate mudder as well.

As it happened, 1924 was the Kentucky Derby’s fiftieth anniversary, or Golden Jubilee, as race officials preferred to call it, and accordingly, momentous changes were announced amid great fanfare. Not only was the race designated the Run for the Roses, but, for the first time, in the opening ceremonies “The Star-Spangled Banner” was replaced by Stephen Foster’s “My Old Kentucky Home,” a song that still causes many native Kentuckians to cry into their mint juleps even before the racing begins. Also, a spectacular new trophy was fashioned that remains the standard design to this day: a nearly two-foot-tall, three-and-a-half-pound solid gold loving cup, with a horse and jockey on the lid.

With the Kentucky Derby’s future thus fortified and “the most exciting two minutes in sports” upcoming, racing fans watched Rosa Hoots take her seat in one of the owner’s boxes at Churchill Downs — the first Native American and only the second woman to do so — ironically, in a year that saw Congress pass the Snyder Act, granting U.S. citizenship to all American Indians. Out on the smoothed dirt track, nineteen edgy horses were led to their places at the starting line — among them the sensational Kentucky blueblood Chilhowee, holder of the fastest 1 1⁄8 miles on record and with a pedigree from Great Britain that would reach to the moon.

When the starting pistol was fired, Black Gold stumbled at the rail and it got worse from there. Hemmed in but still tracking the leaders, he was bumped, fouled, and thrown off, but recovered to shoulder free on the outside and gain on Chilhowee, who seemed to have the race neatly bagged along the rail. In the stretch it was Black Gold and Chilhowee neck and neck, but Black Gold was not to be denied. Jaydee Mooney asked for more and Black Gold gave it all, bursting across the finish wire a half length ahead at 2:05:20. It wasn’t a pretty race, and a lesser horse might have faltered, but as the esteemed racing chronicler John Hervey wrote, Black Gold “won it in race-horse style after a rough race, displaying rare determination.”

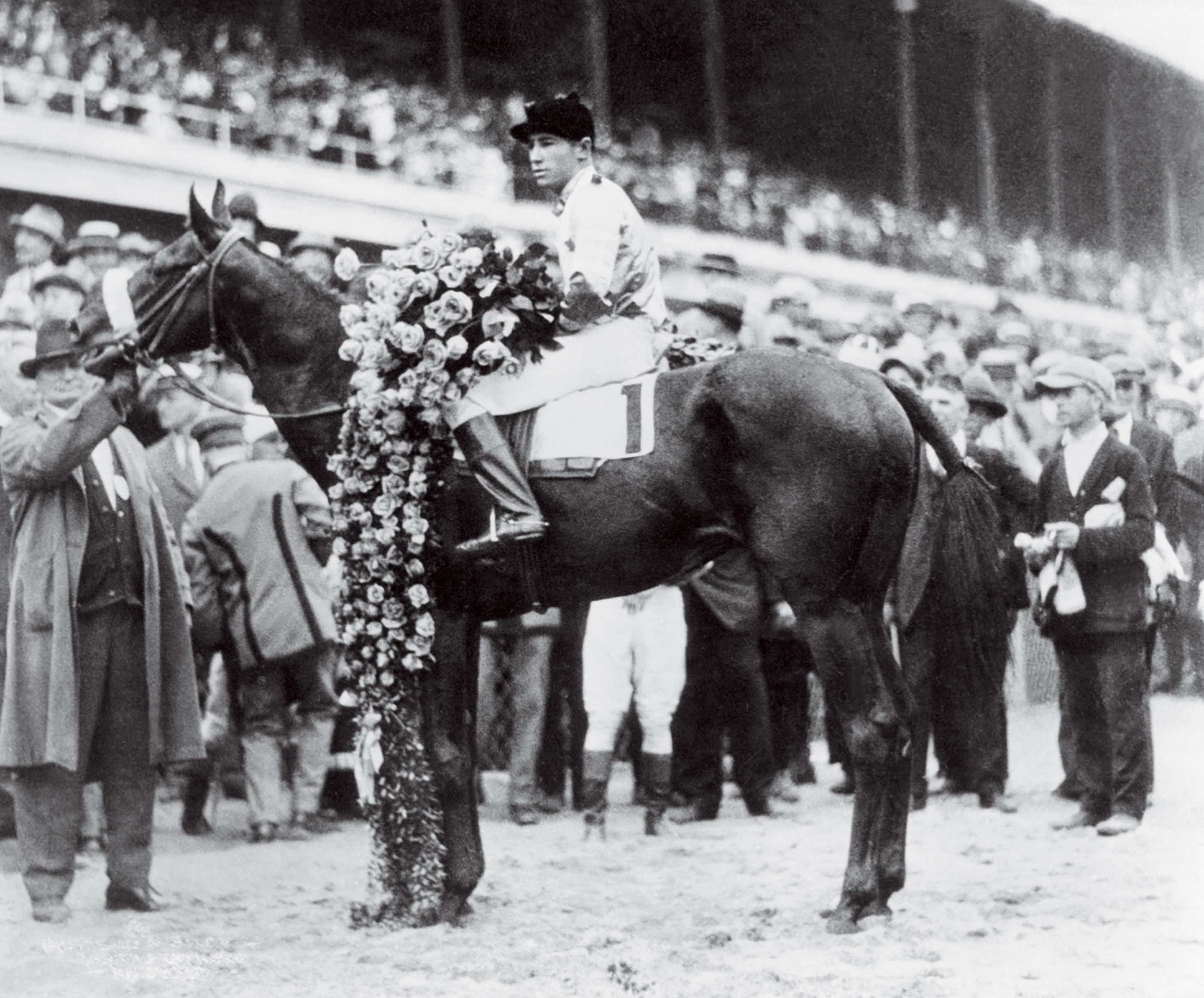

Photo: Photograph courtesy of Churchill Downs Incorporated / Kinetic Corporation

Black Gold won the 1924 Kentucky Derby in "race-horse style, displaying rare determination." That year the three-year-old horse ran thirteen big-time races.

Afterward, Rosa Hoots stood in the winner’s circle with her horse, wearing a gauzy printed dress and her face half covered by one of those funny little 1920s hats that look like a flowerpot turned upside down. She appears in the pictures somewhat embarrassed by all the photographers’ attention, while clutching in both hands the big gold cup that her late husband had promised her in his dying days.

In that era there was no Triple Crown, and while the Preakness and Belmont were undeniably important races, they had none of the cachet they do today. Black Gold was entered in neither of them that year, but went on to win two other derbies, the Ohio and the Chicago, making a total of four in one year — a record that stood for several decades. Moreover, his victory in both the Louisiana Derby and the Kentucky Derby went unmatched for more than seventy years. He finished in the money in eleven of his thirteen starts that year, which is why what happened next seems so puzzling, so unnecessary.

Several years ago I was asked to introduce the movie Seabiscuit at its premiere gala held in Atlanta. During a subsequent conversation with Laura Hillenbrand, author of the brilliant book on which the movie was based, I suggested that she write the story of Black Gold.

“I can’t,” she said, “it’s too sad.”

In two years of racing, Black Gold had earned $110,500 for his owner — some $1.3 million in today’s dollars — an enormous return by any measure. Still, it was customary to keep a horse on the circuit so long as he was viable, or else to put him out to stud, which is what Rosa Hoots did with Black Gold after he developed foot problems. Specifically, at the end of that grueling 1924 season during which Gold ran no fewer than thirteen big-time races, he became hampered by a quarter crack, which is a split in the hoof. It is usually brought on by an imbalance in the foot, and can cause extreme footsoreness and lead to more serious trouble down the road.

Putting him out to stud was, of course, the right thing to do, since continuing to race the horse could only aggravate such an injury. Trouble was, Black Gold turned out to be sterile, a condition not especially uncommon, but an unfortunate one considering that he was a perfect product of his dam’s speed and his sire’s stamina. So, for the next two years he languished in pastures in a kind of horse purgatory, unable to race and unable to mate. By all rights, he should have been converted to dressage, or at least to a saddle horse, so he could spend the remainder of his days enjoying romps across the Oklahoma plains. But for some reason that was not to be, and the blame most likely rests on his trainer, Hanley Webb.

In 1927 it was decided to return Black Gold to the racing circuit. Modern veterinary medicine has ways of dealing with a quarter crack that were unheard of eighty years ago, but perhaps Webb believed that it was not as bad as it seemed, or at least that it would not cause much trouble. But the fact is, racing a horse in such condition is risky: To race, a horse must be in shape, and to be in shape it must train, and training means a lot of hard running, which puts terrific strain on any racing animal — let alone one that has been idle for two years.

Nevertheless, when the 1927 season opened, Black Gold, now a six-year-old, was back on the tracks, where he compiled a record of exactly no wins, no places, and no shows — a humiliating comedown for a former winner of the Kentucky Derby. That, if nothing else, should have told his trainer and his owner that their horse had become an also-ran. What discussions might have taken place between Hanley Webb and Rosa Hoots are lost to history, but when the 1928 season rolled around, Black Gold, obviously still plagued with the quarter crack, again found himself on the starting line, this time for the Salome Purse at the Fair Grounds in New Orleans on a cold January day.

Another horse with his sort of injury might have sulked or shirked, but Black Gold did neither. He was in the running all the way, and thundering down the homestretch trying to make up ground, when his jockey heard the sickening crack that means a broken leg. Even then, he never stopped running, and in one last gallant and astounding effort he somehow finished the race on three legs. But it was too late for anything except to put him down.

Black Gold died that afternoon on the same track where he had won his first race, and where Al Hoots had fallen in love with Useeit back in 1909. He lay barely a stone’s throw from the weathered marble monument that enshrined his mother’s nemesis, Pan Zareta. They said that afterward spectators wandered onto the track, wanting to cut a lock of hair from Black Gold’s mane or tail, and the next day flags were lowered to half staff and New Orleans schoolchildren were let out to attend his burial in the infield next to Pan Zareta.

It is extraordinary when a racetrack acquiesces to such a thing, but in all likelihood it had something to do with the old Kentucky colonel E. R. Bradley, owner of Idle Hour Farm, where Black Gold was sired by his own famous Black Toney. Bradley had purchased the Fair Grounds racetrack a year earlier, and in 1924 he sat in an owner’s box at Churchill Downs along with Rosa Hoots when Black Gold whipped three of his other prized horses in the Kentucky Derby. Nobody ever said E. R. Bradley was anything but a gentleman.

In 1972 Pan Zareta was inducted into the National Museum of Racing’s Hall of Fame, and Black Gold followed her there in 1989. Since then, the Fair Grounds has had its ups and downs, having been destroyed by fire in 1993 and rebuilt, then wrecked by Hurricane Katrina, forcing its racing season to move for a year to the Louisiana Downs in Bossier City. Today the races are back in the location they have occupied for one hundred and forty-four years.

But racing fans no longer have to wonder, as I did as a boy, about those little monuments in the infield. During the winter season at the Fair Grounds, Black Gold was memorialized in a ceremony, and flowers were placed on his grave before the fiftieth running of the 5 ½ Furlong Black Gold Stakes. It was a fitting tribute to an Irishman’s dream and to the small, valiant “Indian Horse” who was mistreated at the last, but always gave whatever he could, right up to the end.