Arts & Culture

The Talented Mr. Toye

The strange story of how William Toye might have forged hundreds of paintings, deceived prominent art collectors, and created a scandal around one of Louisiana’s greatest folk artists

Photo: Erika Larsen

William and Beryl Toye have sixty cats buried in the backyard of their Baton Rouge home, each in its own coffin. William, seventy-eight, builds the coffins out of redwood. Beryl, ten years younger than her husband, digs the holes.

The Toyes are opera aficionados, and for years they named their pets after characters in the musicals of Gilbert and Sullivan, until they finally ran out of names.

“Do you know we’ve had a hundred and six cats since 1977?” William says with no small measure of pride. “Ko-Ko was the first, Yum-Yum was second. If you have all day, I can tell you about every one of them.”

The Toyes never wanted children. “We didn’t want all the yelling and screaming,” William says, “so we adopted cats instead.”

They live in a quiet neighborhood populated with ranch homes built in the 1960s and ’70s. Theirs is the only two-story house on the street, and it’s the only one with knee-high grass and the shorn trunk of a dead tree in front. Beryl Toye grew up in England, and one might call her yard an English garden if it weren’t a fact that she hasn’t tended to it in years. Beryl suffers from agoraphobia, an anxiety disorder that incites feelings of panic if she has to leave the house, and as a result she often goes as long as a month without venturing outside.

Visitors to Keaty Drive say the house looks haunted. The gutters have fallen down, and the fascia board is rotten and black with mold. Junk crowds the front porch: a discarded air-conditioning unit, rolls of stained carpet, a mail carton left to rot in the weather. Inside, there is a large hole in the ceiling of what was once the formal living room. The Toyes made the hole one night at 3:00 a.m. to free their Maine coon, Puggy Wuggy, when the cat got stuck between the joists. During the same crisis, they also carved out the ceiling of the downstairs powder room.

“I contacted a funeral home about where to get gravestones for the cats,” William says. “So I’m going to have a load of gravestones delivered, and we’re going to put one at the head of each grave.”

“We know where they all are,” says Beryl, who is making a rare outdoor appearance this day. “Taddy is here, Janey here.” She stops, brings her hands up to her face, and begins to cry.

“Hebe,” William calls out, pronouncing the name Hee-bee. “I think I saw Hebe Jeebe under the storage building, B.” He looks at his wife and points again. “Hebe,” he says. “Come along now, Hebe.”

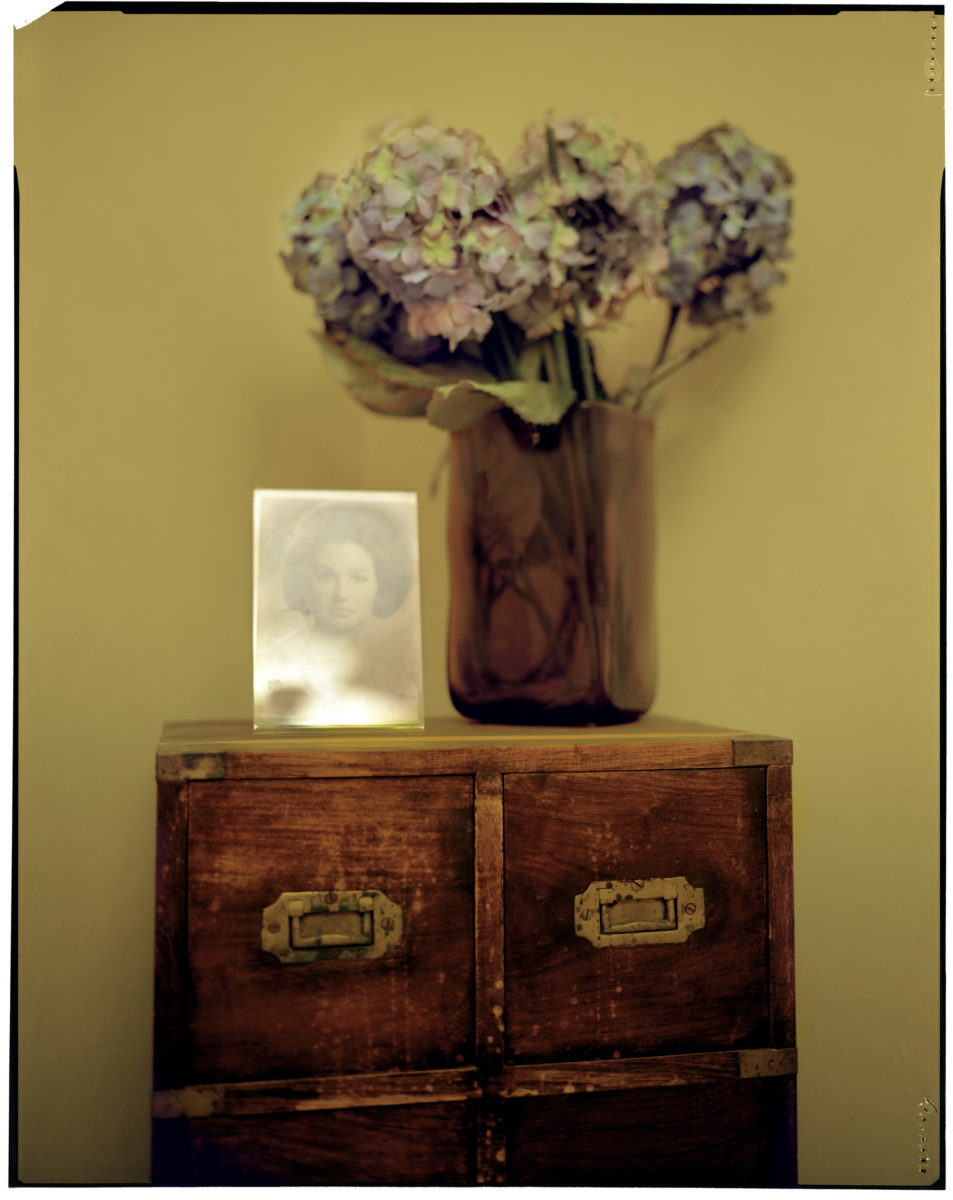

Photo: Erika Larsen

A rare photo of Beryl

“But you told me she was killed in the raid,” I whisper to William, out of Beryl’s earshot. “She was,” William replies. He begins to cry now, too.

It happend on the morning of September 30. Brandishing a search warrant, federal agents descended on the Toyes’ home and spent nearly five hours looking for evidence that the reclusive old couple were more than eccentric cat hoarders. The FBI was investigating claims that the Toyes were also art forgers who had scammed dealers and collectors out of hundreds of thousands of dollars by selling them fake paintings by Louisiana folk artist Clementine Hunter. According to the Toyes, the agents ransacked their home and outbuildings and found only four small Hunters, leftovers from a four-hundred-piece collection that Beryl had amassed decades earlier when she and the artist were friends.

Five months after the raid, the Toyes and an art dealer who sold hundreds of their paintings were finally indicted and charged with three counts each of mail fraud and one count of conspiracy to commit mail fraud. The Toyes remained defiant, and the threat of a federal trial and prison time hardly fazed them. “The FBI just wants us out of the house so they can come back and steal the Degas we have stored in the closet,” Beryl says. “But I have a message for them: We’re not leaving. Let them come get us.”

As many as forty people had participated in the raid, including agents with Animal Control who left with several cats in portable kennels. “It was like a Ku Klux Klan, homosexual, Nazi Germany convention,” Beryl says.

Neighbors congregated across the street at James Breedlove’s house. “I had so many people come over, I could’ve sold tickets,” Breedlove says. “The agents had a card table set up in the front yard, and they were bringing out paintings. They would wrap the paintings in brown paper and log them onto a yellow pad on a clipboard. Finally a fire truck and an EMS vehicle showed up. I learned later that Beryl went bonkers. They took her to the psych ward of a local hospital for three days, but we didn’t understand all this at the time. All we saw was Beryl coming out on a stretcher. It was quite a show, I’m telling you.”

The raid unhinged Beryl, she admits, and she swallowed Valium tablets after telling agents she was going to kill herself. She also cursed and took a swing at one of the investigators. “They were pointing fingers at me, and I can’t paint,” says Beryl. “And then they thought they could trick me. They said, ‘Well, your husband’s confessed to it and we’re going to take him down to Central Lockup.’ And I said, ‘But he couldn’t have painted them either because I bought them from Clementine.’”

William surely has the talent to copy Hunter. While most of the paintings hanging on the walls of the Toyes’ home depict now-deceased pet cats, there are highly competent copies in the mix of great paintings by artists such as Paul Gauguin, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Alfred Sisley, and all came from William’s hand. William once said he might’ve had an important career as an artist had he been able to function better in the world. Like Beryl, he battled agoraphobia, which for a time left him paralyzed with fear if he had to do so much as get in his car and drive across town. William is particularly adept at replicating Claude Monet, the French Impressionist whose canvases sell for millions. “Nobody does Monet better than me,” William likes to boast. “If he were still alive and we both did a water lily painting, tell me the difference.”

Beryl says she finally buckled under the agents’ pressure and took responsibility for producing the fake Hunters. “I said, ‘Okay, I painted them,’” she says. “‘I painted them right after I finished helping Michelangelo paint the Sistine Chapel and Chagall paint the lobby of the Met.’ This of course went above their heads.”

In the commotion the Toyes’ favorite cat jumped the fence into a neighbor’s yard. Twelve-year-old Hebe had cataracts and couldn’t see well. William later found her dead in the street. “Her unseeing eyes were gazing out at me,” he says. “What is the FBI going to say when we share this story with the sixty million cat lovers in the U.S.?”

William says he confronted an agent after he discovered Hebe. “I told him, ‘You want a fight? Go ahead.’ But he just walked away. And so I yelled at him, ‘The nation of cat lovers will know about this. You murdered Hebe.’”

In the backyard now, Beryl has stopped crying. She looks out over the privacy fence that separates their property from a self-storage facility on the adjacent lot. “They’re watching us from the top of that building as we speak,” she says. “The FBI has us under twenty-four-hour surveillance. They see everything we do.”

“Hebe Jeebe,” William calls out.

“They sprayed a special powder on our car,” Beryl says. “Whenever William goes anywhere, like to the market, they can track him from a satellite.”

Photo: Erika Larsen

An early impressionist scene by Toye

“When they were clearing out the land behind us to build that building,” William says, indicating the self-storage facility, “they took out a forest. The guy operating the CAT tractor found a human skeleton holding a high-powered rifle. The skeleton didn’t have identification, but we’re certain he was an assassin hired to kill us. He died back there somehow. It never made the papers, of course.”

Born in either 1886 or 1887, Clementine Hunter spent most of her life at Melrose Plantation, some fifteen miles southeast of Natchitoches, Louisiana, a picturesque town of about eighteen thousand on the banks of the Cane River. Hunter, granddaughter of a slave, picked cotton and pecans until the jobs exacted such a physical toll that she moved into the big house and worked as a maid and a cook. In the early part of the twentieth century, Melrose served as a retreat for writers, artists, and other members of the South’s intelligentsia, many of them residents of New Orleans’ French Quarter who found a patron and friend in Cammie Henry, the plantation’s owner. According to legend, artist Alberta Kinsey left behind some painting supplies after a visit in 1939, and Hunter used them to make her first picture on a window shade.

Hunter produced between four thousand and five thousand paintings before her death on New Year’s Day, 1988, at age 101. Her colorful, simply rendered scenes of agrarian life hang today in museums and appear in major exhibitions dedicated to American folk art, and collectors of Southern art covet her work, routinely paying $12,000 for a superior example. Her paintings are often compared to those of Grandma Moses, but the differences between the two are profound. Moses painted quaint scenes of rural New York, most of them winter landscapes, while Hunter showed the daily activities of an average country black person in the segregated South.

William Toye has never understood the appeal of Hunter’s paintings. “They’re junk,” he says, “and really only good as dartboards.”

The Toyes moved to Baton Rouge from New Orleans in 1994, and in both locations William refused to let Beryl display her Hunters at home. He hates the paintings so much, he says, that he destroyed dozens of them by breaking them over his knee. He put others out for trash pickup, but not without first punching holes in them with the pointed end of a bricklayer’s hammer. Almost as bad, he kept her collection in a garage with a pet door that let cats come in from the cold. “I let them scratch and piss on the pictures,” William says. “And I was happy when they did. I think it improved them a lot.”

He says he has no regrets about how he treated the Hunters even after he learned how much they’d increased in value. Beryl, who says she started buying from the artist in 1969, usually paid between $35 and $50 for a painting. She once sold a group of six through a New Orleans auction house, she says, and earned “top price.” In the early 2000s, that amounted to about $3,500 a painting. “Whenever we sold some, the money went to the cats,” William says. “We go through about five tons of cat litter a year. Can you imagine what that costs?”

Photo: Erika Larsen

Art House

A work in progress

Tom Whitehead knows the Toyes made a bundle selling art, but he doesn’t believe their story about Beryl’s Clementine Hunter collection.

Whitehead, a retired associate professor of journalism at Northwestern State in Natchitoches, was so close to the artist that she called him her “white son.” Beginning in 1969, he visited her at least once a week but never ran into Beryl Toye. He doesn’t recall Hunter ever mentioning her name, either.

In 2005, Whitehead partnered with Art Shiver and edited a book about the murals Hunter painted in Melrose’s African House, an old structure that stands on the plantation grounds. Whitehead was autographing copies one day at a Baton Rouge bookstore when a friend approached him holding a Hunter painting. As it happened, another Hunter expert, Shelby Gilley, who wrote his own book about the artist, had come to the store to see Whitehead. The two men examined the painting, and Gilley, a Baton Rouge gallery owner who died of pancreatic cancer in January, expressed doubts about its authenticity.

Hunter fakes had been circulating since the early 1970s, but those counterfeits were easy to identify. One of her relatives had forged paintings, as had a relative of Cammie Henry’s. Because Hunter painted in a primitive style, she became a mark for yet more artists who found her easy to imitate. What made the painting in the bookstore different was its quality. The forger was clever and highly skilled. He’d painted the scene on vintage board, and his brushstrokes and monogram were convincing representations of the artist’s. But something about the painting wasn’t right. For starters, it was too clean to have originated with Hunter, who typically left smudges on the backs of her paintings and mussed the edges from handling.

Whitehead thought the painting looked like those that had been sold for years by Louisiana dealer Robert Lucky, Jr. Lucky, who declined a request to be interviewed for this story, works today for a high-end art and antiques gallery in New Orleans, and he once sold Hunter paintings from a collectibles store he owned in Natchitoches. Exactly when Lucky’s association with the Toyes began isn’t clear, but the relationship apparently ended in 2003 when Lucky, who’d been accepting paintings from Beryl’s collection on consignment, stopped selling them after customers returned them with complaints that they weren’t what they seemed. The federal indictment charges Lucky with selling some of those paintings again and again, even after he’d learned that they were fakes.

Whitehead claims that Lucky once “blurted out” in a heated phone conversation that he had placed 247 Hunters from the Toyes with dealers and collectors, and Whitehead includes himself among the many who were duped. The artist’s devoted friend, who knew her work as intimately as anyone, had bought seventeen of them with a partner, paying Lucky a total of $55,000.

In many cases the Toyes’ paintings revealed a sophistication that was absent in other Hunters. They were also much busier. Some depicted multiple plantation activities and tracked in a narrative arc. Hunter didn’t paint that way, Whitehead says. Another giveaway was the alleged forger’s use of pink and purple. He liked them far more than Hunter ever did. And there was yet one more problem. “Clementine painted on boards that were fairly standard sizes,” he says. “The Hunters that were coming from Lucky miss the regular sizes, but, then again, every so often somebody would take Clementine a funny board and she’d paint it. But we quickly realized that all of Lucky’s were like that.”

William Toye has never understood the appeal of Hunter’s paintings. “They’re junk,” he says, “and really only good as dartboards”

Whitehead once visited a friend in Arkansas who had a Hunter Christmas tree painting on display in his home. Whitehead says he’d encountered “only about five to ten” such scenes by the artist in forty years. “And so my friend says to me, ‘I’m really fortunate. When I bought this from Robbie Lucky, I told him I had three kids and hoped to give each one a Christmas tree painting. And Robbie said he would check and get back to me. And in two months there were two more Christmas tree paintings.’

“That was the moment,” says Whitehead, “when I realized the forger could do them on order.”

The source of the fake Hunter in the bookstore was an unlikely one. It had come from Don Fuson, a well-known Baton Rouge business owner and contractor who’d amassed one of the finest private collections of Louisiana art and antiques in the state. Fuson was shocked to learn that the painting was no good. He had bought it from a wonderful old man named William Toye.

The hunt for the next big find “has sometimes been like a drug that prevents me from doing anything else,” says Fuson. “The need for more, the adrenaline rush that comes whenever I find something important. This is what’s always kept me going.”

Fuson is particular about folk art, so much so that he usually doesn’t buy it. Although he knew that Clementine Hunter was one of the most popular artists to ever come from the South, he never felt compelled to buy her paintings until William Toye came along.

Their first meeting took place in November 2005 at one of Fuson’s Baton Rouge businesses, Rudolph’s Christmas Shop, when William offered to sell him Hunters from his wife’s collection. According to Fuson, William told him he owned a company in New Orleans that produced stage sets for operas. Only three months before, Hurricane Katrina had destroyed the Ninth Ward warehouse in which Toye Scenic Arts stored its sets. Fuson says William gave him the impression that he and Beryl were Katrina evacuees who escaped with only her Hunter collection and now needed to sell it to rebuild their storm-ruined lives.

Fuson was suffering pangs of survivor’s guilt in the months after Katrina. Just eighty miles down the road in New Orleans, after all, people had lost everything in the storm, and there he was in Baton Rouge in a large home that had suffered no real damage. It only made sense for him to help out the down-on-his-luck old man.

“He reminded me of an old professor,” Fuson says. “He said he didn’t want to sell to dealers, because they’d screwed him in the past. Makes sense. There are unscrupulous people out there who’d take advantage of an old man.”

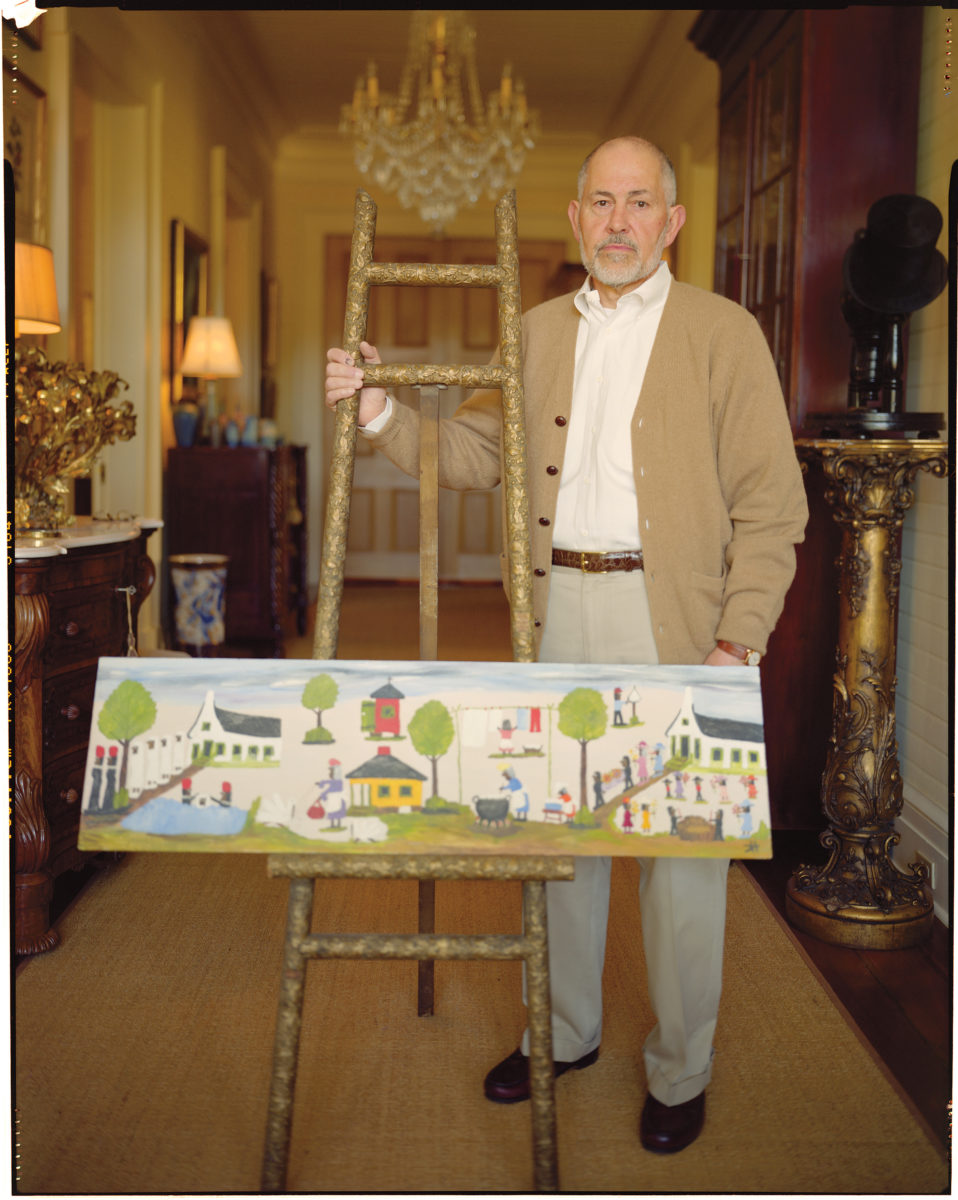

Photo: Erika Larsen

Some of the disputed Hunter paintings that Don Fuson bought from Toye

Before he committed to buy the Toyes’ paintings, however, Fuson showed them to a gallery owner who specializes in Louisiana art. The dealer didn’t question their authenticity. Instead the woman told Fuson she wanted to buy the group, and Fuson communicated her offer to William. The old man liked the price, and Fuson wrote him a check for $5,500, a fraction of what Hunters of such quality were usually worth.

Bolstered by the dealer’s assessment, and hoping to be charitable while also adding another important Southern artist to his collection, Fuson bought eighteen paintings from the Toyes over the next two months, paying $30,000. He sold a couple to his friend Paul Dammers, a Baton Rouge neuropsychologist, who in turn sold others from Fuson’s cache to colleagues at the medical center where he worked.

Fuson isn’t the first to have been impressed by Toye. The old man is a tireless raconteur who enjoys spinning tales about his past as a symphony conductor, an inventor, an opera set designer, and an art collector. In the 1990s, he handed out business cards that identified himself as W. Geoffrey Toye, Ph.D., when his name is really William James Toye and he dropped out of school in the eleventh grade.

Toye says his name was too close to that of his abusive, alcoholic father, William Joseph Toye, and he chose the new name as a tribute to another relative, the English composer Geoffrey Toye. But was he an actual doctor in any field? Beryl insists that her husband has so much musical experience that he qualifies as a doctor, but Toye admits that he was a lazy, unmotivated student who never received a high school diploma, let alone a college degree.

At seventeen, Toye moved from New Orleans to New York to work as a stagehand at the Metropolitan Opera. He lived in the old opera house for a season, he says, “sleeping at night in any room that was empty,” and he claims to have befriended the most important conductors and classical musicians then working in the city, some of whom provided him with apprenticeships. He says he also spent time with artists. “I remember watching Jackson Pollock work,” Toye says. “He’d fling the paint around, and you had to step back or he’d cover you with it.”

Toye moved back to New Orleans in 1951. He worked as an architectural designer for engineering firms making models of buildings and bridges, and he took private lessons in conducting from maestro Massimo Freccia. In his spare time Toye studied art books and taught himself how to paint. It took skill to produce a winning likeness of a great work of art, but Toye also learned to use materials that matched those that went into making the original. He says he even knew the secret formula that Edgar Degas used to create his famous pastels of ballerinas.

Toye made other things too—like bombs. On a lark he flushed one down a toilet in the men’s room of a neighborhood playhouse. “I didn’t stick around to see if the place flooded,” he says, “but I could hear the explosion as I was running from the building.”

By the late 1950s, Toye was battling bouts of anxiety that overwhelmed him whenever he had to leave his home. To treat the condition, he says he underwent successful shock therapy. “I had three sessions,” he says. “That’s all it took.”

William Toye met Beryl Spalding in 1967 when she visited New Orleans as a tourist and a Catholic priest friend brought her over to his home on Plum Street. Beryl had a full, sensuous mouth and thick hair cut in a fashionable bob, but William found her fiery temper as compelling as any physical characteristic. In an argument she could stand toe-to-toe with anyone, including him.

Photo: Erika Larsen

A Toye original

They spent only two weeks together before she had to return to England, and then he romanced her across the ocean with love letters and flower arrangements before asking her, in yet one more hand-written note filled with longing, to come back and marry him. She returned to New Orleans and rented a room in a French Quarter hotel. They haven’t been apart since.

Toye told Fuson a lot about himself, but he didn’t tell him the whole story. As a matter of fact, he left out some of the most interesting parts.

In 1969, when the Toyes were still living in New Orleans, police interviewed them after burglars broke into their St. Charles Avenue apartment and slashed forty-four canvases and stole six others. The majority of the destroyed paintings, William told police, satirized the city’s leading public officials, while a smaller group depicted locations in Storyville, the notorious red-light district in New Orleans that was shut down in 1917. William was scheduled to exhibit the controversial paintings at the city’s Downtown Gallery in less than two weeks, and he says he believes the burglary was a vendetta by politicians who didn’t like how he’d portrayed them.

The Toyes say they filed an insurance claim after the break-in and received “around twenty-five thousand dollars,” roughly the value of the destroyed artwork.

Then five years later William was arrested for allegedly selling fake Clementine Hunter paintings to an undercover New Orleans police detective in a sting operation that received front-page coverage in the Times-Picayune. A photo showed two officers standing with a clutter of primitive paintings, which at first glance looked like original Hunters. The artist was still alive then, and she confirmed that she hadn’t painted them. To fight the charges, William hired one of the city’s top defense lawyers, and although he spent a harrowing day in jail, the case never went to trial.

In 1997, the Toyes were connected to yet another forgery scandal when paintings they consigned to a Baton Rouge auction house were deemed worthless fakes by art experts who questioned why purported top-tier works by the likes of Degas and Henri Matisse were being sold through a small-time operation called the Louisiana Auction Exchange. The Toyes still vouch for the authenticity of their paintings, and they claim that they were the real victims, swindled by a cadre of international drug dealers who used auction houses to steal good paintings from unwitting consigners like them. The thieves, the Toyes say, switched out good paintings with copies and returned the copies to auction houses with questions about their authenticity and demands that their purchases be nullified. The consigners never received payment and, in the end, they were saddled with phony paintings that were worthless.

The convoluted explanation didn’t end there. The Toyes say they also risked their lives by providing the FBI with evidence that expensive antique armoires sold at auction had secret compartments in which the same drug peddlers had hidden narcotics.

Photo: Erika Larsen

Real or Fake

Fuson with one of the paintings in question

As further proof of their innocence, the Toyes argue that Ronald Causey, owner of the Louisiana Auction Exchange, practically served up an admission of guilt by committing suicide in the wake of the forgery scandal. When FBI agents arrived at Causey’s home to arrest him, according to William, Causey had his wife, Sandra, block their entrance, and he retreated to a room upstairs. “There was a gunshot,” William says. “The FBI pushed the door open and went in and found Causey dead.”

“He stole about $1,300,000.00 worth of art from us,” Beryl wrote in a letter to Robert Lucky, Jr., on January 7, 2005. “He was a dangerous criminal who surrounded himself with other dangerous criminals. We…literally hounded him to his death.”

Sandra Causey, who lives today in a small town in northern Louisiana, says that the Toyes’ description of her husband and account of his death are just more cruel lies. “Ron would be the last person in the world to kill himself,” she says. “He died of lung cancer. My husband was a fine, big-hearted person who didn’t like to think people could do bad things to you, and so he trusted Mr. Toye, and the whole time Mr. Toye was deceiving him.

“By the time we finished dealing with Mr. Toye, both Ron and I were convinced he was either completely insane or completely evil.”

As soon as he learned that his Hunter paintings were fakes, Don Fuson and his friend Paul Dammers drove out together to confront the Toyes. “When I pulled up to Keaty Drive, my heart sank,” Fuson says. “The house was scary. And I was astounded by what I saw. We waded through the grass and the things strewn about to the front door, where there’s a sign that says, ‘Do not disturb, go away, keep out,’ something to that effect. It’s not easy to knock on an iron door, so I beat my fists against the wall.”

Toye watched the men through blinds in a second-story window, and several minutes passed before he appeared at the front door. Fuson told him there was a question about the paintings, and Toye invited the men in. After a while Beryl came downstairs, wearing a muumuu and challenging their assertions in a firm, unyielding voice accented by her days in London and Hertfordshire.

Beryl says she was usually alone when she traveled to see Hunter. On occasion, though, she drove up to Melrose with a man named James Lake, a patent attorney from New Orleans who handled her husband’s legal affairs. Lake, now deceased, was a middle-aged bachelor who drove a red Mercedes-Benz convertible and shared her interest in plantation history. William had never joined them, because he was always busy fine-tuning his latest invention. Besides that, he had no desire to meet an artist whose work he despised.

“The FBI doesn’t scare me,” says Toye. “Try standing before an orchestra of sixty-eight musicians. Now that’s terrifying”

Rather than provide Fuson and Dammers with evidence, Beryl told them it was their burden to prove the paintings from her collection weren’t good.

“I was hoping that Mr. Toye would say, ‘Let me get the photo album,’ and there would be forty pictures of Mrs. Toye with Clementine on her front porch,” Fuson says. “But there were no pictures. I was hoping he would produce a phone number of the friend who had visited Melrose with Mrs. Toye, but they didn’t have that, either.”

Fuson and Dammers claim that the Toyes still haven’t refunded their money, as the couple promised. In their defense, the Toyes say Fuson had copies made of the Hunters they sold him, and they provided the name of the likely forger: Robert Moreland, the twenty-nine-year-old son of Margaret Moreland, a well-respected Baton Rouge art conservator whom both Fuson and the Toyes often used to clean their paintings.

Robert Moreland today is an artist based in New Orleans, but he once worked as a restorer and occasionally came in contact with William Toye. Moreland says he considered the old man a friend and was shocked when he first learned about his claims. “Never, never would I do something like that,” Moreland says. “I don’t think I could fake one if I wanted to. It’s just preposterous.”

Moreland says that when he cleaned the Toyes’ Hunters, he noticed something odd. “Usually when a painting is old,” he says, “the older it is the stronger the paint is, but there were times when a little paint would come up when I was using a relatively weak cleaner. And I was like, ‘Huh, that’s coming up kind of easy.’ But what do I know? I don’t know anything about Clementine Hunter, and I definitely wasn’t going to say the paintings were fakes because of that.”

Determined to stop the Toyes, Fuson met with other alleged victims. On one occasion the collectors and dealers went as a group to the state attorney general’s office and presented their stories, but the conference left Fuson frustrated. “The impression I got was that they thought this was a white-collar crime and that rich people were getting hurt and so it wasn’t a big deal,” he says.

Even as word circulated that hundreds of convincing Hunter forgeries had contaminated the market, the artist’s paintings continued to attract collectors and fetch top prices. “Money in the bank” is how Claudia Kheel, director of American paintings, prints, and photos for Neal Auction Company in New Orleans, describes the authentic Hunters that come to her for appraisal. Since 2006, the year Fuson first identified William Toye as the source of his bad paintings, only 27 of 197 Hunters offered at major auction houses went unsold. One painting, a Cane River baptism scene, set an auction record of $19,980 in October 2007.

It’s two days before Christmas, and Beryl stayed up all night tending to yet another crisis with one of the cats. Now in the late afternoon she is still too tired to get out of bed. She remains upstairs in her room, which has the words “Cats in this rm please don’t open door” written in blood-red paint across the door.

Photo: Erika Larsen

Con Artist?

The mysterious Mr. Toye at the door to his studio

Together the Toyes wrote a letter to FBI director Robert Mueller protesting their innocence. They copied the letter to Louisiana governor Bobby Jindal and President Obama. Beryl was so traumatized by the FBI raid that William believes she is suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder. “I think she would benefit from shock therapy,” he says.

The Toyes say they’re as afraid now as when they had their problems with the auctioneer Causey. After that experience, they installed bullet-resistant glass in the windows downstairs. William also set a booby trap outside under a window by the carport. He designed it himself, placing a large sheet of glass on marbles. “Anybody who steps on it will be in for a surprise,” he says.

The Toyes are facing lawsuits brought by Fuson and Shannon Foley, a New Orleans art dealer who claims she paid them $44,000 for bad Hunter paintings. The Toyes say they’re getting by on Social Security. They could sell their hand-painted Degas monotype for $1 million if only they could get it authenticated. Same goes for the Raoul Dufy watercolor that hangs in a sitting room. If a Dufy expert endorsed the painting, they could make $175,000. But they’re the Toyes, and they’ve given up on soliciting positive assessments from the art world.

William has spent the last two hours in a room with a bare cement floor and a vigil light burning in the window as a tribute to one of the Toyes’ dead cats. He plays tapes of old opera performances that he says he conducted. Now he’s listening to a recording of Verdi’s Il Trovatore staged in New Orleans many years before. And suddenly the old man is there again, acting out his memory of the day. He waves an invisible baton, cuing the violins and the French horns, punctuating the music with well-timed beats. William usually walks hunched over and with the aid of a cane, but he is a new man now, stronger, more alive. His worries seem to have disappeared. A loud roar comes up as the soprano belts out a difficult note, and William absorbs the ovation with his eyes closed and a small, trembling smile on his face.

“The FBI doesn’t scare me,” he says. “Try standing before an orchestra of sixty-eight musicians. Now, that’s terrifying.”

He walks outside and points out more graves. Graves crowd the forlorn garden next to the carport and extend along a side fence. They dot the ground under a Chinese tallow tree. Still more fill the leaf-choked area in front of his workshop. He invites me into the storage building. “Here’s where the FBI says we had our Clementine Hunter factory,” he says. “The only thing a Clementine Hunter’s good for is as a stepping stone in a muddy field.”

The door creaks open to a chaotic scene. A pile of debris occupies the middle of the room, and boxes stand stacked against the walls. Paintings executed in various styles are scattered everywhere, though not one resembles a Hunter. William reaches for something on top of the pile. It is a large drawing of a vaguely familiar scene. Disheveled men crowd a shadowy area under an overpass. Some look insane; others hold liquor bottles. Under a sign that says White Tower Hamburger stands a woman, the only one in the picture. She is wearing a dress, a pillbox hat, and high heels. The drawing is signed Reginald Marsh 1952 in the lower right corner.

A painting by Marsh sold at auction for $834,500 several years ago, and his New York Bowery scenes, such as this one, are represented in important museum collections all over the country.

“Is that a real Reginald Marsh?” I ask him.

“Yes, it is,” William replies.

“It must be worth a lot of money. Mr. Toye, why don’t you sell it and make life better for you and Beryl?”

The old man is slow to answer. “I knew Reginald Marsh when I lived in New York,” he says. “I used to see him sketching on the street, and I visited him at his studio and watched him work. He was a weird guy, but we got along.” William removes the drawing from the pile and hands it to me. “Take it,” he says. “My gift to you.”

He closes and locks the door and starts for the house. “Hebe,” he calls. “Come, Hebe. Come.”