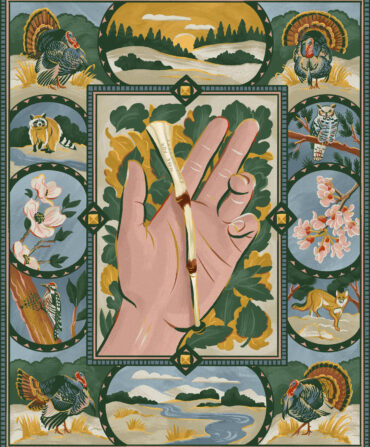

Sporting

The Women of the Palace

From a 1920s cottage on the Georgia coast, generations of Southern outdoorswomen gave a wide-eyed young boy an education in the ways of the water, the ethics of the hunt, and the infinite beauty of the natural world

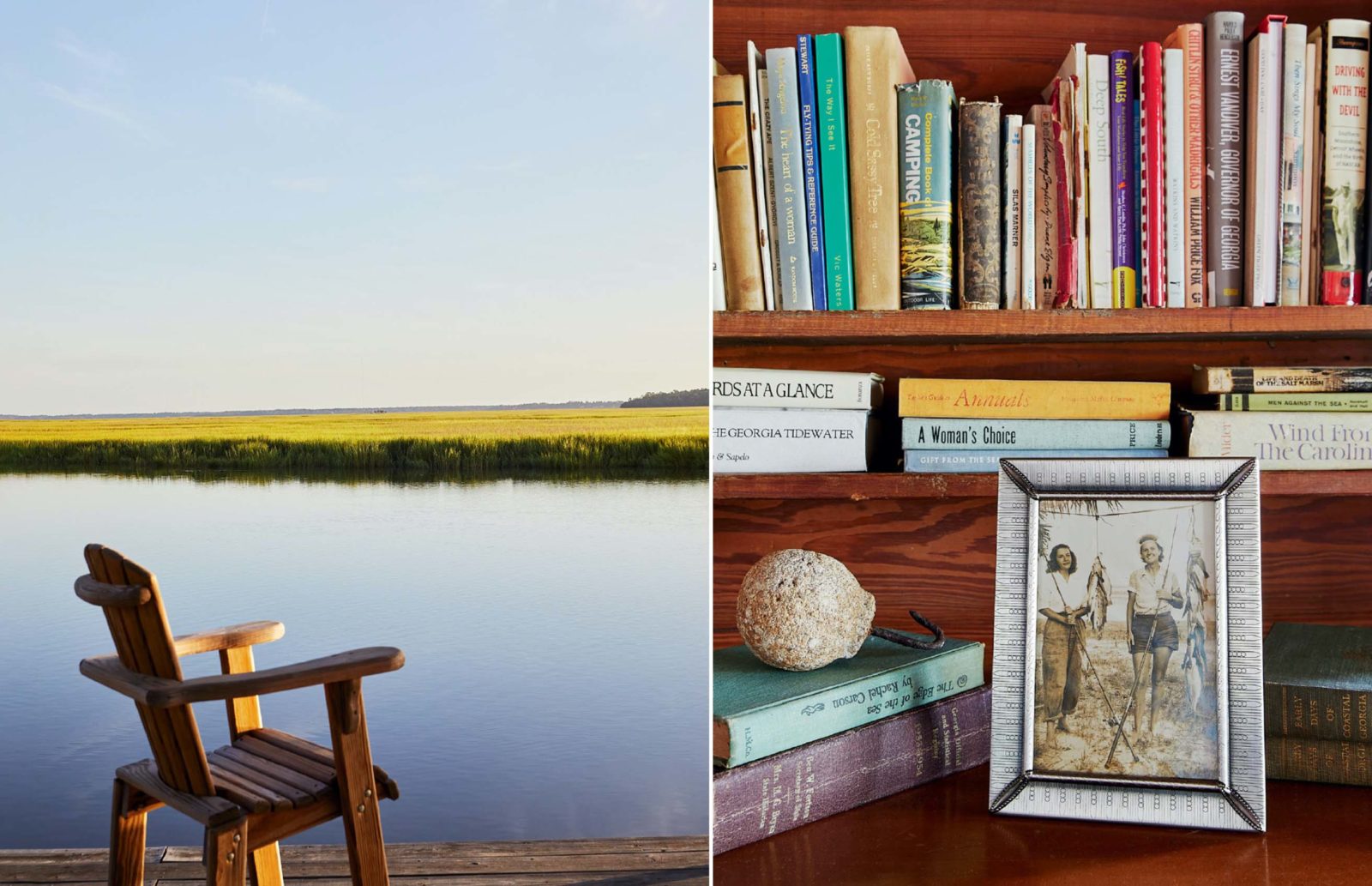

Photo: William Abranowicz

The house’s current owner, Julia Dodd, cools off in the creek.

At Georgia’s ragged edge stands a causeway made of earth piled by hand atop bricks and tires, long grown over with grass and sandspur and sea oxeye. It is a tenuous ribbon of stability cutting through mud and salt and spartina, connecting land and river in a place that is neither, perpetually a tidal shift away from becoming more of one or the other. Looking down its sandy length, I imagine all the footprints laid upon it slowly becoming manifest, one hundred years of emerging soles and toes. There are mine, of course—once tiny and tentative, then confident and bold, now hindered by age and injury. But far more of them belong to people who have meant the most to me, and who made the most of me. In this place, save for mine, they belong entirely to women who wore a path through the outdoors I’ve been trying to follow for fifty years.

Laura Powers Campbell was a waterwoman, living by moon phase and season as much as clock or calendar. She was my great-great-great-aunt by marriage, a connection that seems too remote for a woman whose cackling laugh I still hear decades after cancer silenced it. But family has always been a mutable concept in the South, where questions of provenance are easily lost amid love and dedication. I never thought of her as anything but permanent, as much a part of the ecology of the coast as gray-black mud and oyster shells, and I do not consider it naivete that I assumed I would always be able to run into her tanned and sun-spotted arms to be pronounced her “precious angel in this world.” Ordinary mortality gave the lie to the main of my belief, but because she said it, I still consider myself her angel, despite my many failings in that regard. The truth is she similarly blessed members of multiple generations. They blessed others in turn. In that sense, she achieved the gentle immortality I always ascribed to her.

I never knew Laura’s husband, a man forty years her senior with whom I share blood. Laura and James Campbell, called Skipper, lived and worked in Decatur, Georgia. But in the 1940s and ’50s, tide and moon regularly pulled them southeast upon red dirt roads to a community still barely large enough to have its own name. Driven by the rhythms of the water, with Skipper limited by age, Laura rowed a wooden bateau into the vastness of Doboy Sound, where they could catch flounder and trout and channel bass, decades before fashion made them known as redfish. She was an artist with a cast net, hauling it in bulging with snapping shrimp, building the strength that would pull me so close years later. Thus did a Macon farm girl become a waterwoman.

In a simple house they called the Palace, Laura and Skipper lived with the weather rather than in spite of it. The four rooms, built of #2 yellow pine, stood tucked into the shadows of live oaks, sited there for the same breeze that still ripples miles of marsh. In the cold months, more blankets sufficed for the failures of the single fireplace. For the Georgia heat, there were screens on the windows. They lived life as nature presented it. Over time, in that acceptance came mastery.

Photo: William Abranowicz

Live oaks shade the Palace.

Ultimately, time is all we have. Parting with it to the benefit of another is our most precious gift. Laura gave that gift freely despite being so wracked with pain from rheumatoid arthritis and degenerative disk disease that by the time she moved to the coast for good in 1964, she had to crawl from her boat to pull herself up on a railing after an outing. Even as a child, I knew pain would lay her flat eventually, so arriving at the Palace meant a sprint from the car to her arms. As she swept close fellow arrivals, I snuck into the kitchen hoping to see a galvanized bucket with a towel spread over it, the sound of fiddler crabs scratching within telling me we would soon be hustling down the causeway from the house with our rods to the dock and boat.

Laura was cautious and fearless in equal measure. She taught by doing and expected me to learn the same way, whether she was biting into a raw chicken neck “to get the juices flowing” before tying it onto a crab line or getting a stingray off a hook or teaching me how to dock and secure a boat against a fast-moving tide. I was not yet ten years old the first time I found myself driving a boat wide open, her hand on my shoulder as she calmly explained how to quarter a shrimp boat’s wake or avoid shifting sandbars. But Laura’s wisdom was not limited to rod and net. In the decades before I knew her, before pain stole a piece of her life, she hunted squirrel in the woods, duck in the swamps, and marsh hen in the creeks. More grandly, days not commanded by life in Decatur or spent at the Palace found Laura and Skipper near Tallahassee, Florida, at a quail plantation called Foshalee, where my great-grandfather Louis “Bub” Campbell, Skipper’s nephew, was the manager.

Photo: William Abranowicz

From left: Laura Powers Campbell (right) with a 1941 catch; a view of the marsh; vintage fishing rods and a Stevens .410 that belonged to the author’s grandmother.

If Laura taught me how to be an outdoorsman, at Foshalee she met the woman who would teach me why. Bub’s wife died young, leaving him to raise his daughters, Julia Francis and Betty Ann Campbell, who would become my grandmother “Nana,” on thousands of acres. Laura was nine years older than Betty Ann, and their connection became some perfect blend of friends and sisters. More unusual for the time, they were outdoorswomen in the richest meaning of the word. The things they learned together over decades, under towering Florida pines and on Georgia waters, still color how I enter nature, with an appreciation bordering on reverence and a hopefully soft step.

Bub did not ignore the finer aspects of education expected of Julia and Betty Ann in the 1930s and ’40s, but he lived a life squarely in the province of men—one of dogs and quail and turkeys and horses. With their mother gone, a Black woman, Carrie Weaver, mothered the two girls, raising them into a society she herself would never be allowed to join. I sometimes wonder how much of the forty-eight years of joy I experienced with Nana I owe to the woman who raised her. Whatever the percentage, I know I can never fulfill the debt I owe Mrs. Weaver, or the many women like her. In that, I am hardly alone in the Deep South.

Originally hired as the kennel manager and trainer, Bub was a dogman who rose to manage all of Foshalee for its Northern owners, people with names like Whitney and Vanderbilt. Cited for his expertise numerous times by the famed naturalist Herbert L. Stoddard, he lived his passions and raised his girls to know them. But true outdoorswomen are rarely the product of one person’s tutelage, and Foshalee was rich with teachers.

Mr. “Country” Hand was a renowned turkey caller, known for killing a turkey while shooting backward from a galloping horse. I cannot imagine a better name for a man of his time and place, and he gave Nana an uncommon education in the ways of the natural world. She loved to tell of the time when she was ten and Mr. Hand put her in a blind. He admonished her not to move and sat well behind her to call. Fifteen turkeys walked by her unchallenged, disappearing the way only turkeys can. Exasperated, Mr. Hand asked her, “Betty Ann, why in the world didn’t you shoot one of those toms?” She answered, “You told me not to move!” But turkey hunting was simply a beloved distraction at Foshalee. Quail were the mainstay, and Nana was forever marked by the outsize passion engendered by the bobwhite.

Nana helped Bub entertain quail-hunting parties, seeking coveys on horseback and from horse-drawn wagons, dogs coursing through wire grass to point and honor one another. She learned the patterns of the birds, and when it was time to burn the grass under the pines, she fished for bream and rode for the simple pleasure of being on a horse. In pictures from the time, with her seated in the saddle, shotgun in hand, the smile on her face is as beatific as those in photos seventy years later in which she holds my daughter, her first great-grandchild. Laura and Skipper were there too, for covey after covey bursting from lespedeza in numbers of which we now only dream.

When the hunt was over, Nana accompanied them eastward to the Palace, trading her Stevens .410 for salt air and a bent fishing rod. I keep that Stevens stored in a gun safe for my daughter, a wood-and-steel manifestation of the gifts given by women who went before her. She may hunt, or she may not. But I mean to honor that legacy, and her, as best I can by giving her the option to know the things treasured by the women who so influenced her father.

Photo: William Abranowicz

From left: Yellow pine in the living room; the Palace’s front porch.

Age and life force changes, none more so than for women, too often expected to marshal their resources for the betterment of others. When Betty Ann Campbell married Robert Lee Russell Jr. in 1949, she took what Bub had left her and bought nearly six hundred acres of pine, oak, and pasture in Northeast Georgia. There she made a home, decorating it in colors meant to evoke the feathers of quail and pheasant. Nana traded hunting for rearing five children, granting each a deep appreciation of the landscape and their own place within it. They roamed the farm, fishing in the pond and hunting during the seasons as Nana sat on her breezeway counting shots, asking for the story behind each on their return. I was her only grandchild for the first twelve years of my life, and though I lived a lesser version of my mother and her siblings’ experience, Nana was no less engaged in connecting me to the world’s natural cycles. I pulled bass and bream from her pond as soon as I could hold a rod, often with her shouting, “Hallelujah, dahlin’!” My introduction to hunting was less glorious.

I was nine years old the first time I killed a warm-blooded creature. I was newly possessed of a BB gun, and my prey was a flock of cedar waxwings eating berries at the bottom of Nana’s back pasture. Standing at the edge of a mass of bramble and privet, I levered the gun again and again, firing and missing the birds from a distance of no more than six feet. I finally wounded one irretrievably, but insufficiently to relieve it of its suffering. It was not hunting, simply killing, and I understood the difference too late. Panicked, I ran for Nana, struggling through thigh-deep grass as the bird’s tiny beak opened and closed ever more slowly in my fist. I had never known a time in my short years when my actions elicited anything but her signature phrase, “That’s wondaful, dahlin’!” Now she sadly asked why I would do such a thing, explaining that killing without purpose is nothing more than unconscionable waste. Forty years later, the shame of it still brings a sting to my cheeks, and I refuse to kill anything I will not eat.

Too often life is sad poetry. As her father had before her, Nana lost her life’s love young. In the wake of my grandfather’s death, she stopped riding, fearful of an accident leaving her five children without a parent. But if she gave up many of her early loves, she passed them to two generations who understand the simple joy of watching a hummingbird buzzing just outside of reach or a whitetail buck bounding through a field, consumed by the rut.

Laura had no children, but as she helped raise Nana, so she helped raise her children, on the farm and at the Palace. At the coast they, and later I, lived immersed in the landscape. If I learned the ethics of the hunt from Nana, I learned the thrill of driving a boat at full throttle, a deep vee of white wake behind me, from Laura. Better still was both of them in the boat, rods rattling in the wind. In the thirteen-foot skiff Nana bought for Laura, we drove all out for the twenty-minute run to the dock at Post Office Creek, where Laura taught me to drop purple-backed fiddler crabs on hooks along the creosote-soaked pilings, keeping our lines taut and gently lifting and settling our rod tips as we waited for the nearly imperceptible bite of sheepshead feeding on barnacles below.

Time has since rendered some of my experiences with Nana and Laura irreplicable, like the close encounters I had with bottlenose dolphins in those less aware days. But the love of nature I got from Laura means I am happy now to keep my distance, to tread ever more lightly, to leave less wake. The things we did not know aside, the ethics Nana and Laura taught me still hold. Laura loved the author Robert Ruark, himself raised in North Carolina’s Cape Fear region, where I now live with my wife and daughter. “You might as well learn that a man who catches fish or shoots game has got to make it fit to eat before he sleeps,” he wrote in The Old Man and the Boy. “Otherwise it’s all a waste and a sin to take it if you can’t use it.” Fish was for eating, not packing a freezer. You neither exceeded the limit nor took fish that didn’t meet regulations. You packed your own gear, carried your own gear, and on return, maintained your own gear. Only then could you turn your attention to other things.

With no television at the Palace, dusk was for Skip Caray calling the Atlanta Braves on the radio and Laura calling raccoons in from the marsh so I could feed them in my lap. Injured raccoons lived in her house, secreting silverware behind the couch that we later retrieved for our own dinners on the screened porch, no matter the season. Once darkness fell, Laura loved to take me swimming amid whorls of bioluminescence before reading to me. Havilah Babcock, the brilliant sporting essayist and University of South Carolina English professor, was a staple. Though Ruark’s words again seem most apt: “Anybody who reads this book is bound to realize that I had a real fine time as a kid.”

Photo: William Abranowicz

From left: The sleeping porch; a 1933 field trial trophy and a megalodon tooth.

Nana passed last year, and the farm soon after. But the Palace stands as it has since 1926, four rooms at the nation’s southeastern edge anchoring me against modernity’s currents. Waking to sunrise under layers of winter quilts on the screened sleeping porch, I still feel the promise of magic in the morning chill. When my feet hit the floor, worn smooth by a century of similar awakenings, I know the simple value of things that have always been there. When I shuffle to the end of the bed to put on yesterday’s clothes, the oil stains on the floor from outboard motors stored clamped to the footboard remind me that the Palace has always been a gateway to the natural world, where Laura truly lived without shield or insulation, and the source of so many of the gifts she and Nana gave us.

Laura’s rods rest where they always have, in a hollow in the living room built next to a similarly purpose-built gun cabinet. Crossing the room, I step through French doors to a breezeway, part of an addition built in 2000. Cold bites my bare feet as I cross concrete to ascend wooden steps into a great room, soaring ceilings and #2 yellow pine evoking a chapel. I am moved to glory every time I enter. Looking across the causeway to the marsh framed by hanging Spanish moss, all of it burnished in gold and fire, I hear Laura’s and Nana’s voices calling me a “precious angel in this world,” telling me, “That’s wondaful, dahlin’!” Then another, clearer for its actual presence: “Morning, baby. What do you need?”

Photo: William Abranowicz

From left: Sunrise on the dock; Betty Ann Campbell (left) and Laura.

My aunt Judy, Julia Brevard Russell Dodd—Nana’s daughter, my mother’s sister, and Laura’s great-great-niece—bought the Palace in 1989, the year before Laura passed. The two having spent enough of their lives together that Laura named a boat the Judy B, it was a transfer less of ownership than responsibility for a woman who considers herself the place’s caretaker rather than owner. Judy carries on her own version of Nana’s and Laura’s outdoor traditions. “I love seeing three-year-old girls shucking oysters,” she says. “I love seeing little boys and cast nets. Life at the Palace was a simpler time that is still here if you look for it.”

Leading children into the marsh and immersing them in its story, cooking from Laura’s wild-game cookbooks and with recipes written in Nana’s hand, Judy perpetuates a time when children spent as many hours bathed in sunshine and salt spray as they now do the flickering light of their devices. On Judy’s dock, my daughter caught her own first fish. In kayaks, Judy leads us to a sandbar to collect sharks’ teeth, and in her skiff, to the rich history and biology of Sapelo Island, twenty minutes away. Always present is the legacy Laura and Nana set before her, one she accepted along with the deed to the Palace. It is a heavy obligation, creating another generation of outdoorspeople in a place so rich in memories, where even after fifty years I am compelled by splendor to stop and stare as my daughter skips down the causeway, adding her footprints to those laid so long ago.