Sporting

Tour the Ultimate Shotgun Collection

A trove of classic doubles brings America’s golden age of shotguns to life

Photo: Andrew Hyslop

Eric Klein’s first job was in a gun shop in northern New Jersey. He was fifteen years old.

“Everyone thinks of New Jersey as Newark,” he says from his house at Brays Island Plantation, a 5,500-acre sporting-focused community near Beaufort, South Carolina, where live oaks frame Lowcountry views of maritime forest and marsh beyond the windows. “But that was wild country up there, with a heritage very much like the South. Everyone hunted.” Clerking in a gun shop was a dream come true, but Klein, who is now seventy-two, recalls one of his earliest tasks with a nearly palpable shudder.

Photo: Andrew Hyslop

Eric Klein in the gun room at his home.

One of the shop’s largest clients was the Palisades Amusement Park, across the Hudson River from New York City, where the shooting galleries in those days still used .22 ammunition and a lot of it. The cartridges were shipped from the manufacturer to the gun shop, and it was Klein’s job to break up the shipping crates and burn them in a potbellied stove.

“They were beautiful wooden Winchester cases with the gorgeous dovetail corners,” he murmurs. “Worth a fortune today.” There is genuine sorrow in his voice.

It’s tempting to consider that the passions of Klein’s sporting life as an adult have been a partial amends for those smoke-filled hours feeding history into the fire. If so, he’s repaid the debt with interest, for Klein now shepherds a spectacular collection of American-made doubles from what is considered the golden age of American shotgun manufacturing.

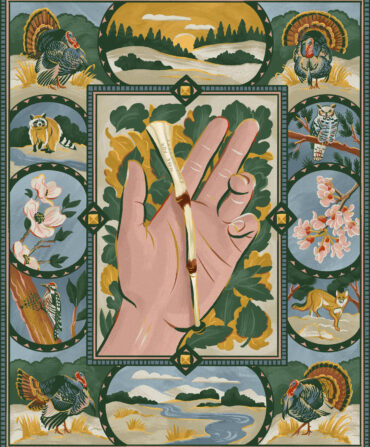

Photo: Andrew Hyslop

Engraving on the receiver of a Parker Brothers double made in 1927 and once owned by T. A. Peterman, the founder of Peterbilt trucks.

Beginning shortly after the Civil War until World War II, firms such as Parker Brothers, L.C. Smith, A.H. Fox, Lefever Arms, Ithaca, and in the later years Winchester produced classic double-barreled shotguns with a degree of craftsmanship and an approach to ornamentation that have made them highly collectible. Most American doubles were made in a wide range of grades, from inexpensive field guns to elaborately figured and engraved arms that would rival European efforts. Parker, for example, made a Trojan-

grade shotgun that sold for twenty-five dollars and an A1 Special that sold for six hundred dollars during the Great Depression.

Klein’s collection of approximately one hundred shotguns takes in a grand sweep of that history. In a classic gun room that opens into the sprawling living spaces at his home, soaring wooden cabinets hold ranks of some of the most sought-after American doubles. Drawers are filled with more.

Klein pulls down a Parker AA with a set of both 20- and 28-gauge barrels. The AA was Parker’s second-highest grade, with Circassian walnut stocks and fine engraving. Made in 1927, this gun was once owned by T. A. Peterman, the founder of Peterbilt trucks, and custom-engraved inlays of California quail flicker on both sides and the bottom of the receiver.

Pulling together entire runs of guns is a particular interest of Klein’s. He owns a 28-gauge Parker in every grade except an A1 Special. It’s on his list, he says, “if I can stand the pain.” The collection holds all of the seven main grades of the Ithaca .410 NID (the NID stands for New Ithaca Double, introduced in 1926), including one of only two grade VIIs the company ever produced. The other was stolen from its owner and has never been recovered.

Photo: Andrew Hyslop

An Ithaca .410 (left) and an A.H. Fox 20-gauge.

Like most collectors, Klein is not immune to an object of seductive provenance. He owns guns with ties to historic families, such as the Wrigleys and the Chryslers, and arms from noted shooting clubs such as the New York Athletic Club. But it is the gun and its place in American firearms history that draw him to a particular model, not the celebrity. An A.H. Fox 12-gauge owned by Teddy Roosevelt, for example, brought in more than $800,000 at auction. “But I have three of the same model, and they’re all much nicer than the Roosevelt gun,” Klein says. “An unusual or interesting provenance might drive the price up, but that has little value to me.” He is enamored with the working histories of shotguns in his collection and still takes a few of the historic pieces to the field for a workout. He shoots trap weekly with a Parker single-barrel trap gun and often hunts quail with a few of the old doubles.

Klein’s evolution as a gun collector began not long after those appointments with the potbellied stove in New Jersey. When he was sixteen years old, he purchased a Parker VHE 16-gauge shotgun—a low-grade Parker, but still a classic. “You talk about a stretch for a kid,” he says, laughing. “But I was already working hard to feed my passion for shotguns—at the gun shop, delivering newspapers, and working in a deli.” For years he went through what he terms a period of “accumulation more than collection.” He went through a Browning phase and amassed Winchester lever-action rifles. He bought lower-grade guns in high condition; his affinity for the working-class aesthetic took root early. He sold most of his first collection in 1981, during the early years of starting and running a business that manufactured commercial kitchen components. But the collecting resumed almost immediately. He scoured newspaper classifieds and old gun shops. Estate sales in New Jersey retirement communities often paid off.

Photo: Andrew Hyslop

The gun room, with black walnut cabinets and heart pine walls.

As his business travels around the world increased (his company had facilities as distant as England and Holland), Klein was exposed to the European model of aristocratic gun ownership and manufacturing, in which most firearms were shuttled between different guilds of craftsmen—barrels made in one place, actions in another, engraving and woodwork elsewhere. But back in Jersey, he says, every facet of society owned guns and hunted. And U.S. gunmaking factories typically operated under one roof, a process that seemed charmingly democratic.

“The manufacturing process for these guns was as much a melting pot as was American society,” Klein explains. The more he traveled, the more he realized how much he loved American-made shotguns. Prior to World War II, he says, not nearly as many people played golf and tennis. “They belonged to gun clubs, everything from a small club where they would drive deer during the hunting season to the big fancy clubs with manicured trap fields. And these guns are pretty representative of all those experiences. They cover the entire spectrum of society.”

The glory days of the American double ran headlong into technological advances and mergers in manufacturing industries in the first half of the twentieth century. Parker, Fox, and L.C. Smith were all gobbled up by larger American gunmakers. According to Klein, the rise of the autoloading shotgun was a death knell for the venerable double-barrel, along with the Depression and World War II, which put the skids on domestic recreational shotgun production.

But for three-quarters of a century, American shotguns reflected a country coming into its own as a cultural, political, and economic powerhouse. “For me,” Klein says, “collecting these types of guns is a physical, tactile way of experiencing that history.”