Travel

A Voyage Down the St. Johns

To find the primeval heart of Florida, take a journey down a river in time

“Like the emotional desperadoes who came—who still come—to Florida seeking a geographic cure for their past, this river has a complicated persona.”

—Bill Belleville, River of Lakes: A Journey on Florida’s St. Johns River

So that’s what we are? Emotional desperadoes? Clearly we are seeking a geographic cure for something out here. Why else would we be on this remote blackwater river, churning along at five miles an hour, overwhelmed by the exotic flora and fauna—and the deep history—that engulf us? Below: alligators, turtles, snakes, manatees, shellcrackers. Above: herons, egrets, eagles, kites, and, in the words of one crew member, “more ospreys than pigeons at the Varsity.”

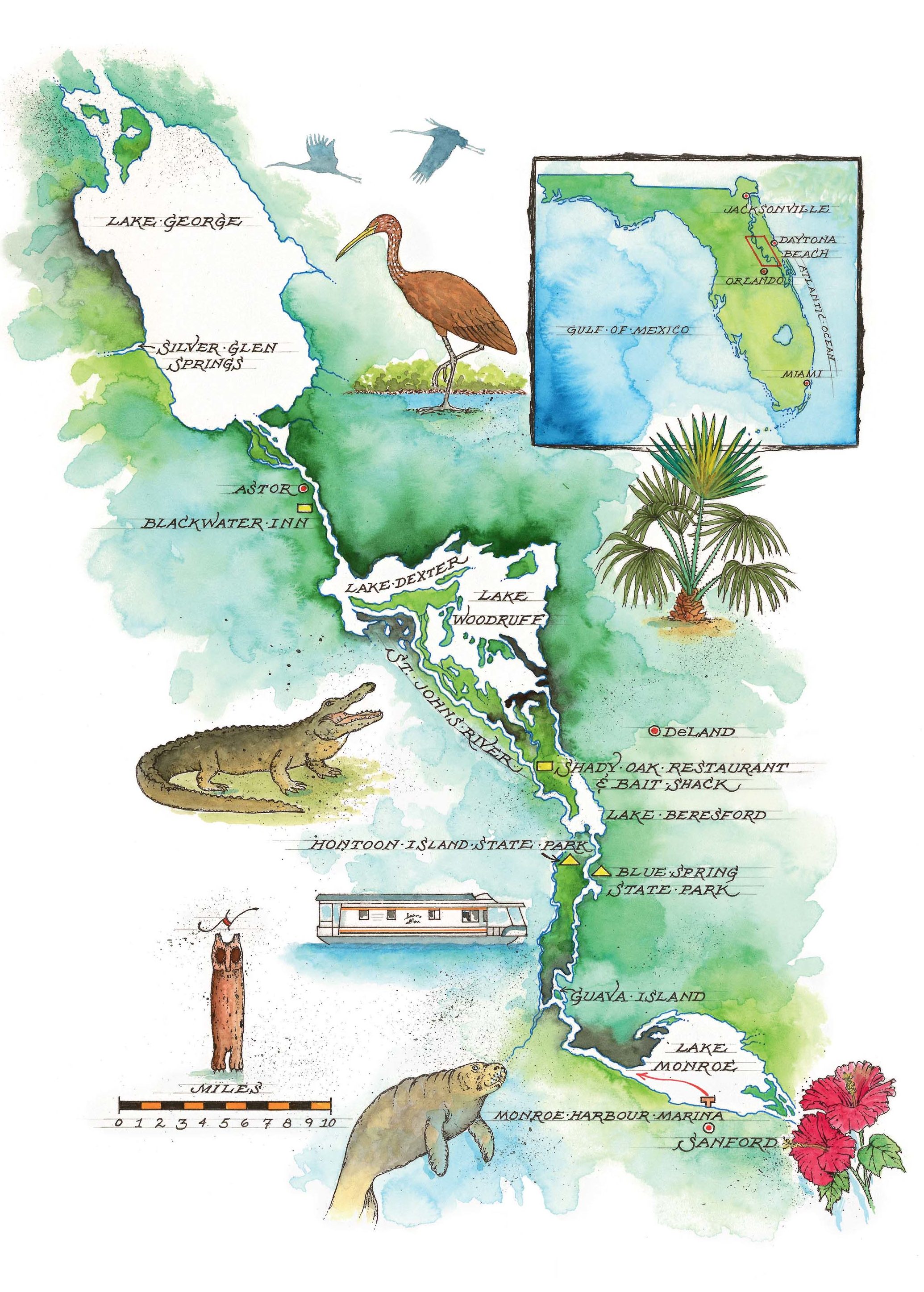

Aiming to see as much of the St. Johns River as we can in a week, my crew and I had gathered on a brilliant May afternoon at a marina on Lake Monroe in downtown Sanford, Florida. Close by is the spot where the last paddle wheeler, once a ubiquitous craft on the river, concluded its final voyage in 1929. Our vessel is not a steamboat, but the fifty-five-foot houseboat Southern Belle—provided, outfitted, and delivered by our new friends downriver at Holly Bluff Marina in DeLand.

Whatever houseboats lack in handling ease or élan, they are ideal for excursions like ours. The river and its string of lakes, creeks, and canals can become suddenly and treacherously shallow, and these boats draw very little water. The dearth of civilization on our route—no grocery stores, drugstores, or liquor stores, and few restaurants—requires a self-sustaining vessel, and the Belle’s accommodations are capacious. Her open bow is a railed deck with a dining table, a gas grill, a ceiling fan, and comfy chairs. Just inside sliding glass doors is a big open room that includes the helm station, a living room, and a fully equipped galley with a real refrigerator, a four-top stove, a microwave, a TV, and a sink. Beyond that are three staterooms and two heads, each with a comfortable shower. We have stuffed this floating box with the necessities of life, as we see them: coolers of food and beer, cases of wine and drinking water, snorkeling gear, rum, binoculars, cameras, whiskey, and a stack of books on birds, fish, history, and paleontology.

Four kayaks are stacked on our stern, and behind us we trail a sixteen-foot aluminum skiff with a twenty-five-horse outboard. Up top is a deck big enough to hold a dance on, with lounge chairs, another steering station, and a Bimini top.

Call me captain. My wife, Kate, is navigator. Two friends from my college days complete the crew: Susan—blessed with an encyclopedic recall of birds, plants, and fish—is our naturalist. Her husband, Don, is first mate and mixologist—enormously handy, coolheaded, and patient.

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

The crew gathers before hitting the water.

Each of us has our own reasons for signing on. For me, the promise of Florida has provoked my imagination since I was a boy growing up in Georgia. Annual car trips down there were as close as my family ever came to exotic. Susan and Don live in old coastal Florida, and are drawn to both nature and indigenous history. Then there’s Kate, one of that rare breed, the native Floridian who grew up near here in small-town Central Florida. Her family photo albums shout Old Florida—filled with gators and fish and boats. A piquant memory from early in our relationship stars a brother-in-law of hers arriving for Thanksgiving dinner by airboat.

One family photo in particular hangs heaviest over me. Young Kate and her brother and sister on the stern of an old Danish wooden sailboat that had been refashioned into a thirty-eight-foot houseboat bearing the name All Hours. I have been hearing about the family adventures aboard this boat in and around the St. Johns for more than thirty years. Can this retro adventure possibly live up to her memories and expectations? Is there really anything left of Old Florida, or are we on a ghost mission?

Photo: Peter frank edwards

Watching the moonrise while anchored on the St. Johns River just off Lungren Island.

The St. Johns was the first great river in North America explored by Europeans—in the 1500s, almost 250 years before Lewis and Clark went west—and for a long time it was the only route into the mysterious interior of La Florida. At 310 miles, it is the state’s longest river and one of the few major waterways on the continent to flow north. Promoted as the “Nile of America,” it became Florida’s first tourist attraction, drawing curious vacationers from the 1870s well into the 1920s.

The author Bill Belleville, whose elegiac book traces his journey from the vague headwaters of the river—in a swamp west of Vero Beach—north until it flows into the Atlantic just above Jacksonville, captures the glory of that era:

Steamships, which first hauled cargo up and down the river for early settlers and rugged frontiersmen in the 1830s, became larger and fancier, accommodating visitors lured by blue sky dreams here in the land of flowers. These archetypal snowbirds descended on the swampy peninsula in a mad quest for health, wealth, and adventure, riding the “highway” of the St. Johns each winter into the heart of known Florida, like today’s snowbirds ride Interstate 95 and the Florida Turnpike.

Travelers cruised south from Jacksonville, dining and sleeping on the steamboats, then staying longer in the luxury hotels and boardinghouses that sprang up along the riverside. They fished the blackwater lakes and swam in the clear artesian springs that feed the river. Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee both visited. Grover Cleveland was here. Winslow Homer painted here, the poet Sidney Lanier wrote a guidebook that included the river, and Harriet Beecher Stowe settled into a winter home on the St. Johns.

The St. Johns is now classified as an American Heritage River, and the navigable portion of it we are on is the forgotten artery that flows just east of the elevated “ridge” dividing a stretch of the Florida peninsula lengthwise. For much of the way, it winds through a semiprotected corridor, roughly twenty miles wide, that includes the Ocala National Forest, a series of state parks, and various government preserves. This narrow terrarium sustains a wildly diverse ecosystem with hundreds of unusual plant and animal species, and the river is dotted with the pre-Columbian ruins and middens of the Timucua, and some remnants of Seminole and other indigenous tribes. Today, one scientist says, the St. Johns is an “unseen river.”

From left: Exploring by kayak; a nest of ospreys along the St. Johns.

Fueled and stocked, we chug north out of Lake Monroe, crossing under three bridges, including the noisy Interstate 4 span, a main artery to Disney World, barely fifty miles away. Now we are in the river, snaking along a narrow stretch of rich tannic water the color of tea, lined on both sides with thick forest—giant sabal palm, live oak, cypress, magnolia, draped and dotted with ferns, bromeliads, trumpet vines, orchids. The air is crisp and aromatic. Very little development shows along the way, mostly small fading fish camps or waterside motels, remnants of the postcard era. The river and its banks are remarkably free of the usual human litter. We see few other boats.

Everyone, I sense, shares my excitement—glee really—to find ourselves on a boat in this patch of jungle (which, I point out, is where Johnny Weissmuller swung through the trees in the filming of those old Tarzan movies). The reality of contemporary Florida, so nearby, is slipping off us like skin off molting snakes. We aren’t just random twenty-first-century sojourners on some boat trip. We are time travelers in search of various pasts, afloat on a raft headed north, which is down, the St. Johns River.

Illustration: michael francis reagan

The trip’s route along the St. Johns from Lake Monroe to Lake George.

Romance aside, driving this sled turns out to be a real bear. I say that as a reasonably experienced mariner who spends a lot of time driving a variety of boats in tidal conditions. But this is different. You don’t steer a fifty-five-foot box with no skeg or keel underneath, and a superstructure sticking twenty-two feet into the air, so much as try to suggest where it might go. There is no sweet spot where you can just aim and let it run on course. Guiding it is a constant process of turning it one way, then quickly adjusting in the other direction before it actually goes the first way. If you want to turn left way ahead, you need to start right here—or maybe back there.

Our first overnight destination is a little dot of land called Guava Island, lying to one side of Emanuel Bend, a curve in the river. Our objective is to maneuver this beast into a notch on the riverbank, where my deckhands (Don and Kate) can leap off and wrap lines around two trees to hold the boat fast to the bank. But a wind has kicked up behind us, overriding my efforts at the helm. Our first pass does not go well. The Bimini jousts with a tree limb and loses. It’s a noisy tussle that gets all our adrenaline pumping. After a couple of passes, we manage to secure the boat to the island with no damage we can’t fix.

Our new home for the night is a small hammock of trees and vines. We double-check our lines and knots, then exchange sighs of—if not exactly accomplishment—relief all around. Don, fresh from a semi-Herculean tie-up effort, puts glasses into everyone’s hands. They are filled with what will be the house drink for the duration of our journey: margaritas, exquisite in their simplicity, which he has handcrafted and lugged along by the gallons. That first one, that first night, may have been the most welcome cocktail I have ever been handed.

Ashore, we spot the shells of the huge apple snails that are the favorite food of the river’s most distinctive bird—the limpkin (a crane relative), whose eerie, screeching cry is like no other. Off our stern, a great blue heron stands atop the channel marker, scanning the dark river for its supper. Just across the channel the water is topped with an expanse of yellow pond lilies and water hyacinth; through them, gliding stealthily along the surface, are the unmistakable eyes of a large alligator.

We stay out of the water but dive into our shrimp and corn stew, recounting the small victories and near misses of our first day. We are soon aware of a pair of eyes staring right at us from just twenty feet away. It is a giant, aristocratic barred owl, settled into the brackets of a sabal palm, unbothered by our presence. “Who cooks for you? Who cooks for you-all?” it asks into the night.

The Blue Flower full moon is two nights away, but the night sky is well lit and sparkling as we adjourn to the roof deck to take it all in. Frogs, crickets, screeching victims of the night, all ring out in a strangely soothing cacophony. The air is unusually cool, and we have shut down the AC and the generator. The mosquitoes and no-see-ums have taken the night off. It is a damned fine evening for settling in and seeking a little inspiration from one of the Bartram books I have brought along.

America’s first great nature philosopher, John Bartram set out on the St. Johns in 1765 as the king’s botanist (George III of England), traveling for several months with his son “Billy” Bartram and three others (one an enslaved man) in a flat-bottomed bateau. On a later trip around the South, the younger Bartram wrote his classic Travels, with descriptions of the St. Johns that have influenced all comers since, including John James Audubon and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, who never came here but borrowed from Billy’s work in crafting “Kubla Khan.”

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

Navigating an oxbow on the river.

Up early the next morning, we press farther downriver away from civilization. The river and the boat are both lazy, so there’s plenty of time for taking in the vast array of wildlife. Since Susan is the naturalist, her job is to station herself with binoculars and reference books and point out every living thing we might otherwise miss.

Here is her log entry from our first full day:

This morning: purple gallinule perched across the creek in the sunlight. Underway: ospreys carrying large fish, and others standing on numerous low nests. Pileated woodpecker. Sandhill cranes with chicks out across a marsh. Young limpkins. Little blue herons. Snowy egrets. Red-shouldered hawks. Swallow-tailed kites. Black vultures. Alligators of all sizes. Red-bellied turtles sunning on logs. Carolina wrens.

Settled into the routine of the boat, we approach our next stop: Blue Spring State Park, our first freshwater spring, which bills itself as the real Florida.

I’m not sure exactly what to expect at Blue Spring, but here’s what Billy Bartram saw on his visit in 1766:

A vast fountain of…mineral water, which issued from a high ridge or bank on the river, in a great cove or bay…it boils up with great force, forming immediately a vast circular bason…and here are continually a prodigious number of fish; they appear as plain as though lying on a table before your eyes, although many feet deep in the water.

We beach the Belle at the park and disembark with our snorkeling gear and some sporty inner tubes. We drop our two-dollar fees into the honor box. Today’s Blue Spring remains magnificent. Each day it gushes out 102 million gallons of fresh, clear rainwater that has been trapped for thousands of years far below the earth’s surface. The largest spring on the entire St. Johns, it is the winter home of some four hundred West Indian manatees. These giant dough-faced mammals, which average twelve hundred pounds and ten feet in length (sometimes reaching three thousand pounds), migrate here in winter for the year-round water temperature of seventy-two degrees, four degrees above the lowest they can tolerate.

Photo: PETER FRANK EDWARDS

Identifying the area’s raptors.

Whether this is a sound environmental idea or not, visitors are allowed to swim into the boil, then float down the creek. We hop right in and are surrounded by all manner of fish: Florida gar, alligator gar, longnose gar—all look like they swam out of a dinosaur book. We see a wide variety of sunfish—redears, redbreasts, bluegills—along with massive blue catfish. Thousands of gambusias, or mosquito fish—the first aquarium fish sold in America—swarm the waters. And the invasive party crashers giant tilapia prowl here too. Above the mouth of the boil, serious free divers in wet suits, GoPros strapped to their foreheads, disappear into the cave entrance from which the water pushes out. We take a more leisurely approach, snorkeling and tubing down the lazy creek.

We were warned we might be too late in the season for the manatees, but they are right here in the spring with us. At one point, several of the beasts swim right under my tube, which I hang over, gawking at them through my mask. Belleville notes that when you make eye contact with manatees, they appear as humans in manatee suits, then he goes on to wonder if we appear to them as manatees wearing human suits. I hope so.

The crowd around the spring is sizable but not overwhelming, and wonderfully diverse: Old and young. White and black and brown and yellow. American and European and Asian and Latin American. We are all drawn here by the same magnet that attracted humans from the Native Americans forward: the magic of the spring and its inhabitants. Adults ooh and aah at the manatees, children squeal and laugh at the strange-looking fish and frolic with abandon in the see-through water. At one point, I come upon Kate in her tube, holding on to a tree limb, eyes closed with a big smile on her face. When I ask why she isn’t snorkeling, she responds, “I’m just listening to all the sounds of the park. There’s so much joy here.”

Photo: PETER FRANK EDWARDS

A lone island.

Soon after that, back on the bank, she is reminded that this really is Old Florida when she spots a bona fide coral snake (deadly) slithering near a park picnic table. We delegate that issue to the authorities and reboard the Southern Belle in search of a tranquil spot to settle in for the weekend. With guidance from rangers, we don’t go far, just across the St. Johns from Blue Spring into a placid creek. Here we tie up to a big black walnut and a white ash in woods on the lower end of Hontoon Island State Park—itself a major attraction for its wilderness beauty and indigenous artifacts.

Photo: PETER FRANK EDWARDS

The Hueys share a moment while grilling dinner aboard the Southern Belle.

With the sun lowering, we slide into our kayaks to explore the creek and the surrounding marshes. The sounds of frogs and woodpeckers and screeching limpkins float over us, and we are never out of sight of an alligator or three sharing the water with us. Gathered back at the boat, we fire up the grill and observe the show that surrounds us.

Susan’s log entry:

Friday cocktail hour, rosé wine, entertained by a sweet-faced limpkin that became our camp mate—then went on the hunt, submerging its whole head digging for apple snails and freshwater mussels. Big snail found, limpkin carried it to the bank, hammered with its beak, and feasted on lumps of escargot.

Billy Bartram, who drew a limpkin, was especially taken with what he called the “crying bird.” His illustration survives, but as the editor Thomas Hallock notes in his edition of Bartram’s Travels on the St. Johns River:

…the crude engraving fails to capture the limpkin’s gangly, doe-like grace. But the illustration does connect us. The same bird…is still found on the St. Johns. Readers of Travels who see a limpkin in the wild hold a special kinship to William Bartram. His presence cuts across centuries.

For us time travelers, our “Night of the Limpkin” does just that, pushing us deeper into a slower, unplugged routine, more connected to all the sights and sounds and smells of the nonhuman life around us. Unlike, say, the Colorado River, the St. Johns doesn’t overwhelm you so much as envelop you. It is subtle, but powerful.

The night sky, as seen unobstructed from our roof deck, is a mesmerizing daily reminder of our place on the planet. Saturday brings the big show—the Blue Flower full moon—and it is spectacular. Perched on top of the jungle, we bathe in what seems like filtered daylight that changes color with the arc of the moon.

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

From left: The Blackwater Inn on the waterfront in Astor; fellow river travelers.

Sunday we awaken to a workday. We are due to pick up our photographer at the little town of Astor (yes, those Astors), an eighteenth-century riverside settlement originally named Spalding’s Upper Trading Store, where Billy Bartram based himself for months. That means making thirty miles downriver on a day of heavy boat traffic. We take a short pit stop in DeLand at the Southern Belle’s home port, Holly Bluff Marina, for refueling, ice, encouragement, and yet another map. Then we settle in for the grind north, downriver.

Parts of the central St. Johns are more populated than others, and we have to open a couple of drawbridges for passage along the way. The scenery remains beautiful, with the river widening out into flatter vistas of marshes, swamps, and fields, all hosting ibis, egrets, herons, and cranes. Above us, bald eagles, red-shouldered hawks, and flocks of kites begin to appear in profusion, along with the ospreys—mature birds, nestlings, and nearly fledged young—that become downright ubiquitous. If we’ve been lulled into forgetting that our little nature corridor remains so close to civilization, Sunday on the waterway brings that delusion of seclusion to a noisy end.

Enter the notorious “Florida Man” (of internet fame). Suddenly paradise is invaded by roaring airboats, pontoon boats, ski boats, cruisers, cigarette boats, and Jet Skis, rocking us with sweeping wakes and blasting our ears with music—Skynyrd, Creedence, bro rock. Tribal markings are on full display: elaborate ink, tiny thong swimsuits, and a few huge banners flying from sterns advertising the captains’ preference in politics. As with the alligators, we leave one another alone.

Nearing Astor, we tie up on the backside of a little spot called Lungren Island, then take the skiff to meet our photographer, Frank, who is waiting for us at the Blackwater Inn, a popular old bar and restaurant anchoring the waterfront. After a quick snack of fried catfish fingers, smoked mullet dip, and cold draft beers, we pile into our skiff and head back to the Belle for the night. We retire early, resting up for the next day, when we will face our biggest navigational challenge of the trip. Destination: Silver Glen Springs, just off the western side of Lake George, a few miles north of Astor.

Photo: PETER FRANK EDWARDS

Taking a dip at Silver Glen Springs.

At twelve miles long and six miles wide, Lake George is Florida’s second largest lake. Its eastern half is off-limits to civilians because it’s an air force bombing range. On the west lies Silver Glen Springs, another state park and one of the river’s most popular destinations. The trick, at least by boat, is getting there. The lake—once ocean bottom—is so vast and flat and featureless as to be disorienting. The channel across the lake is well marked. Silver Glen Springs is not. You are supposed to hit a certain marker, then turn and follow a compass course to a barely noticeable slit in the bank that leads to the springs. We soon discover our boat compass is haywire, but Frank pulls out his iPhone compass, and we recover in time to locate the cove opening. At this point, all hands are manning their battle stations, and I am holding my breath. To avoid running aground, a lot has to happen quickly, with no room for error. Don and Frank run back to the stern to open the engine hatch and raise the prop at a precise point, which keeps us moving but reduces our steering ability. Relying on the GPS chart, Kate has to guide me through a tiny channel that winds around various shallows and islets. Then we arrive, entering a gorgeous lagoon of crystal-clear water—only to find it packed with other houseboats.

Having come this far, we press on, dropping anchor just inside the lagoon, which turns out to be the perfect spot for what feels most like a genuine tropical vacation. Here we can leave the boat at will, by jumping in to swim or snorkel or tube, or by kayak to explore, or by skiff to range farther. It’s not that alligators don’t hang out at these springs: it’s just that they can’t lurk invisibly underwater, which reduces the worry of stealth attack.

The springhead here is the main attraction. It churns out sixty- two million gallons a day, which attracts not just tourists but also lots of fish, including several hundred five- to ten-pound striped bass that seem oddly out of place hanging above the boil. (These fish are no longer anadromous migrators to and from the Atlantic; they live here year-round.) The huge blue crabs inhabiting these springs are another sign of the river’s incredible diversity. Some of us wander up a creek and find a series of little boils bubbling out of wetlands, like quicksand. We wonder if one of them could be Jody’s Spring from Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings’s The Yearling. (Legend has it that the region’s most famous author modeled it on one she saw here on a voyage up the St. Johns.)

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

Mullet school near Silver Glen Springs.

The ability to enter Silver Glen Springs by boat seems like a wonderful, anachronistic privilege on the one hand, but it comes with a dark side. Unlike at Blue Spring, some who gather here show little interest in the natural magic of the place, more interested in showing off the mega sound systems of their boats. Belleville, speaking specifically of Silver Glen twenty years ago, sums up the problem:

It clearly illustrates the classic argument between National Park Service advocate John Muir and Gifford Pinchot, architect of the U.S. Forest Service—between the closely supervised preservation of wilderness and unlimited public use on demand. It is an argument historically paralleled since the earliest days when Europeans first ascended the St. Johns, each of them pleading to appreciate it or clamoring to exploit it.

The dilemma persists. But I’d still rather be here than the Daytona International Speedway—a mere fifty miles east of us.

Once the day boaters depart, the lagoon becomes remarkably tranquil. Margaritas. Grilling out. Sunset swims. Our time on the St. Johns is running short, so we go all in on dinner: lamb chops, kofta, grilled vegetables, tzatziki, rice, and lots of red wine. Call it Greek Island night. We take the skiff for a cruise back out into the lake. A grinning retiree anchored at the mouth displays his just-caught largemouth for our approval.

Waking up in Silver Glen, starting with a quick plunge into the clear water, evokes a morning in the Caribbean—exquisite. Because of how we anchored, extracting the boat from the cove appears to be a challenge, but by now we are experts. Kate jumps into the water and uproots the anchor, while Don and Frank discover they can stand in the water and push the boat around 180 degrees. Now it’s an easy shot back into Lake George and then up the St. Johns to Holly Bluff Marina for what will be our longest cruise of the trip. We are totally relaxed and absorbing the beauty as we putter along unhurried.

The wildlife is as abundant as ever, but Susan’s final log focuses now on flora:

Water hyacinth. Pickerelweed. Red hibiscus. Spatterdock, about to bloom—a.k.a. yellow pond lily. Yellow cow lily. Lance-leaved arrowhead. Alligator flags. Red-blossomed coral bean.

As we near DeLand, we tie off behind an island and head out in the skiff for our last supper. Continuing our immersion in Old Florida, we pull up to the sagging dock of the Shady Oak Restaurant and Bait Shack, which looks just like it sounds. Perched over the St. Johns at a place called Crow’s Bluff, its dockside tables are ideal for drinking cold draft beer and watching the sparse river traffic pass by as the sun fades. We order an authentic cracker dinner, which we get in quantity: catfish, frog legs, alligator tail (all fried), hush puppies, potato salad, coleslaw, and baked beans. More beer. Then key lime pie. It all ranges from not bad to excellent.

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

Catfish and frog legs at Shady Oak Restaurant.

On our way back, we wander down various creeks following tempting signs to fish camps that we never find, until the closing in of darkness forces us home. All of a sudden, it’s become hot and muggy, and some nasty biting flies descend on us. For the first time, we close up the boat, crank the generator, and turn the AC on.

Still, all is well. We went in search of Old Florida, and we found it. It is hiding right here in plain sight—in the middle of America’s third largest state (21 million residents), which lures 127 million visitors a year, qualifying it as the top travel attraction in the world. Few of them come to the St. Johns, or even know where it is. How long this sanctuary can hold the tide against the encroachment of civilization is an important question.

The next morning we dock the Belle at Holly Bluff and head home on the vast maze of interstates that vein twenty-first-century Florida. The reentry is stark. Desperate not to surrender the river magic entirely, we try to conjure the St. Johns through music in the confines of our car. For that we dial up the English composer Frederick Delius, specifically, his Florida Suite, inspired by the time he spent tending his family’s citrus plantation on the St. Johns in the 1880s. Its intentionally evocative movements—“Daybreak,” “By the River,” “At Night”—sweep and soar, crackle and soothe. A French horn is not a heron, a piccolo not a limpkin, but it sort of works.

I didn’t really find a “geographic cure” for my past out there, and I may still be an “emotional desperado.” But I can certify that a week on the St. Johns River—with the right people, weather, and attitude—is a magnificent way to treat whatever ails you.