Adrienne Cheatham didn’t fully understand the beauty of kimchi until she began cooking professionally. The flavorful interplay of fermented cabbage and heat did more than just teach her about Korean cooking. It shot her right back to her childhood, when a funky condiment she knew as cha-cha—a.k.a. chowchow, the spicy pickled relish built from green tomatoes, cabbage, and peppers—was on kitchen tables in her Mississippi relatives’ homes. “It shows you how much different cultures have in common,” Cheatham says.

Cheatham’s mother was a white Midwesterner from Chicago who met her father, a black Southerner from Jackson, Mississippi, when both worked at the Oscar Mayer plant in Chicago. They married, and his family was concerned that his new wife wouldn’t know how to cook proper Southern food. So his grandmother Lula and two aunts traveled north with their cast-iron pans and some seeds for a garden.

“For a month and a half or two months, they showed my mother how to cook Southern food,” Cheatham says. “They really taught her the fundamentals of Southern cuisine, which is finding the food that is the freshest and closest to you.” The flavors and techniques have remained steady influences, whether Cheatham was working as executive sous chef at New York’s Le Bernardin or a contestant who almost won season 15 of Top Chef, or, now, as the creative force behind the SundayBest pop-up dinners she hosts in venues around Harlem, New York, where she lives, and other cities around the country. “Southern cuisine is the original American cuisine,” she says. “You had to preserve things without refrigeration and had all this great produce to work with.”

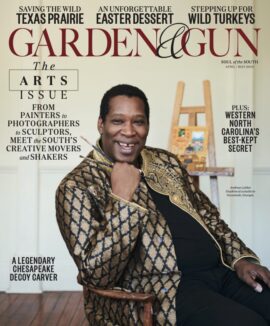

Johnny Autry

That ethos inspired her collard kimchi. Originally, Cheatham’s idea was to apply the Korean preservation technique to turnip greens in place of the napa cabbage that is the traditional base for the dish. “But collards are such an integral part of the cooking I grew up with,” she says, “that I knew I had to use them for this.”

Blanching the collards first helps soften their fibrous leaves. Fermentation fed by a tablespoon of sugar does the rest. The base recipe comes together quickly but requires time for the real magic to happen. Leave the jars in a cool, dark place for a few days and taste the collards once small bubbles begin to form. You can eat the kimchi then, or leave it for a few more days to give it more punch. Then transfer the batch to the refrigerator, which slows the fermentation.

Johnny Autry

Cheatham uses the tiny salted fermented shrimp called saeujeot, an ingredient that’s available at markets with a large selection of Asian ingredients or online, but they’re not necessary if you can’t find them. “As long as you have the fish sauce for flavor and funk, you’re good,” she says.

The collards add character to a simple supper of shrimp and rice, or work well with grilled meat. But Cheatham’s favorite pairing is with fried chicken or good barbecue.

“You might never go back to coleslaw,” she says.