Pruitt took this portrait of the Fraser family on Christmas day 1953. Berkley Hudson sits on his mother’s lap. “Pruitt took my picture from the time I was a baby until I was about nine,” Hudson says. “He was dark-haired and wiry, had ears that stuck out, and he exuded a gregarious personality.”

Photo: Courtesy of University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Libraries

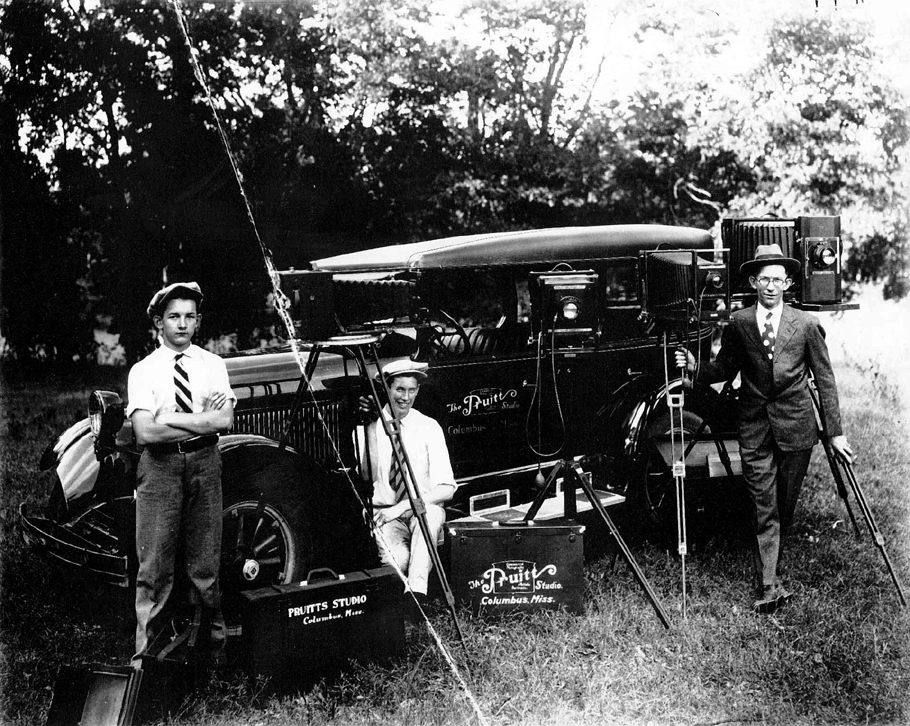

Pruitt (far right) and his camera, his son Lambuth (far left), and his brother Jim, circa 1925.

Photo: Courtesy of University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Libraries

A preacher with a baptismal group on the bank of the Tombigbee River, circa 1930s. “When I found these pictures and I saw white people standing behind the Black people, and then I saw Black people standing behind the white people, I thought, What’s going on?” Hudson remembers. “There’s plenty of pictures of both Black baptisms and white baptisms in the South, but you don’t see this. And now we know that they were there at the same time, watching each other get baptized.”

Photo: Courtesy of University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Libraries

A portrait of a young girl with a canebrake rattlesnake.

Photo: Courtesy of University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Libraries

Here, a woman sits for her picture on wooden porch steps. “I’ve thought a lot about how because he was white, Pruitt could move in both worlds,” Hudson says. “There’s still a lot of things that are missing from Black community life, but what he does give us is these beautiful portraits.”

Photo: Courtesy of University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Libraries

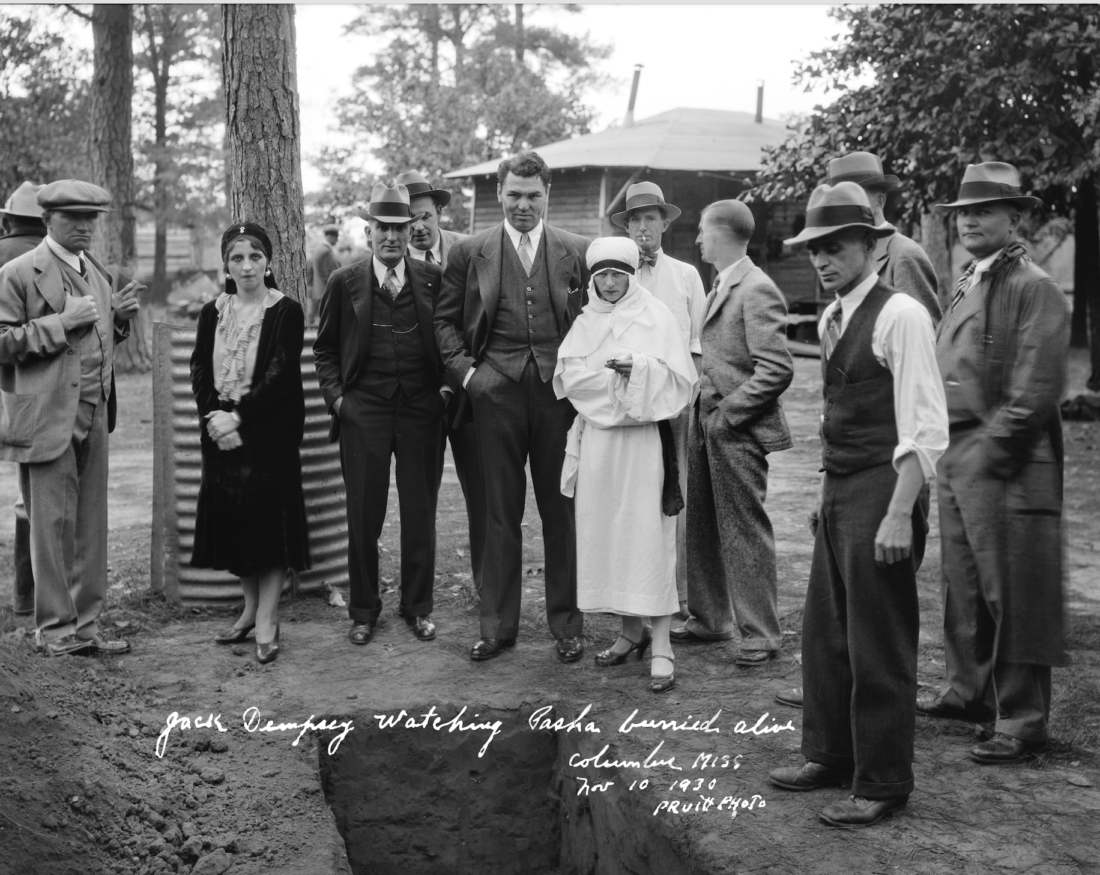

“In November 1930, early in the Great Depression, former world heavyweight champion Jack Dempsey came to Columbus from Los Angeles to rendezvous with a ‘buried-alive’ carnival act managed by Truman Capote’s father,” Hudson writes. On November 10, 1930, Pruitt captured Dempsey (center and hatless) with Madame Flozella and Truman Capote’s mother, Lillie Mae Faulk Persons (dressed in black), by the grave dug at the Lake Norris Fishing Club.

Photo: Courtesy of University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Libraries

“This image you see actually is the only thing that I had to go off of, and it took nearly a decade for me to find who this was,” Hudson says. After combing through newspaper archives from 1913 and 1960, he found Pruitt’s photograph on the March 8, 1934, front page of the Commercial Dispatch, with a caption that read: “Sylvester Harris, negro of Lowndes County, Miss., has plenty to be happy about. Recently he telephoned President Roosevelt in a plea to save his home from mortgage foreclosure, and a few days later an extension was granted on the mortgage. Here’s Sylvester, with his mule, in front of his farmhouse near Columbus, Miss.”

Photo: Courtesy of University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Libraries

A circa 1940 fire in Catfish Alley, so named for the prolific amounts of fresh catfish sold and fried there. “From the late nineteenth through the mid-twentieth century, Catfish Alley was a one-block-long strip of flourishing Black businesses, a product of racial segregation: restaurants, pool halls, the town’s first Black-run drugstore, barbershops, honky-tonks, a birthing center, and Black doctors’ offices,” Hudson writes.

Photo: Courtesy of University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Libraries