I am not a driver. As one who has spent her entire adult life in New York City, I have never needed to know how to operate several tons of metal on an asphalt track. Now, however, after more than a year of sequester and confinement, I find myself wishing that long, long ago I had mastered the rules of the road. I muse back on good times spent riding shotgun or simply rolling along in the back seat without a worry about navigation or speed limits, with my eyes free to view the countryside and the roadside attractions.

As my mind goes over the multiple road trips I have taken, one keeps pushing itself to the top of the list. That trip runs from the Memphis airport to Oxford, Mississippi, and then rambles farther into the state to Greenville. I was an annual regular on those Mississippi roads for ten years in the 1990s and then again for another five in the late 2010s.

My initial ride on the Oxford section of the journey was my first trip into the reaches of the Deep South. For me, a Northern-born Black person who had no Southern relatives, Mississippi was a place of memory and fear from flickering television sets of my youth; it was the fabled South, the South of racial memory and unspeakable history. Simply the word Mississippi was daunting. What would the road hold? What was in store for me? “Oxford Town” sung by Bob Dylan was on the playlist that accompanied me, and when I crossed the line from Tennessee into the Magnolia State, I pumped up the volume on “Mississippi Goddam” by Nina Simone, which had been one of the anthems of my younger days.

On my first trip, I was riding shotgun with my sister-friend, Daphne Derven, who had flown in from California. We met at the Memphis airport with its brown-tiled concourses perfumed with the aroma of barbecue, went through the rental formalities, and then headed out toward Oxford, the site of the conference that would result in the formation of the Southern Foodways Alliance. We attacked the road at speeds that were illegal in my neck of the woods. Just after we’d exited the airport’s urban sprawl, the entrance signs for Graceland loomed up. We zoomed past. I prefer Big Mama Thornton, cannot imagine peanut butter and bananas, and am not really fond of shag carpets and velour excess. My friend agreed.

Soon, a large sign welcomed us to Mississippi, and the clinging vines that I would learn were kudzu began to cover the trees. The haunting and gothic history of Mississippi was palpable in the landscape, and I felt its atavistic ringing in my blood. I thought of Bobbie Gentry’s Tallahatchie Bridge and those strange-fruit-bearing trees of Billie Holiday.

On that initial trip, the cotton was high and as yet unharvested. When I saw the first white fields blooming in the autumn sun looking like so many snow-covered fields, it was as though I had returned to a place seared in my memory. We screeched to a halt and I jumped out, headed over a gully and into some poor man’s cotton field where I availed myself of several branches, risking arrest and initiating what would become a decade-long ritual of the annual thieving of the cotton. I scampered back up bearing an armload of white bolls peeking out from leathery brown pods, marveling at their prickly tenacity and the pristine white of the cotton, a small personal reparation.

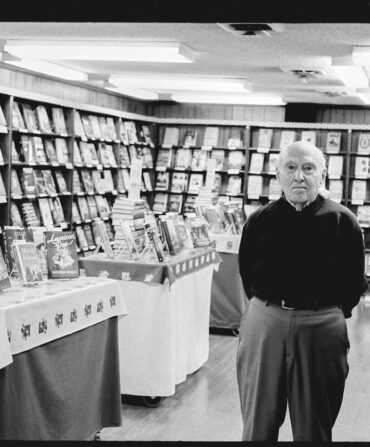

The road was fast and straight, and the trip lasted a scant hour and a half. As we neared the turnoff for Oxford, we came to a halt at Betty Davis Bar-B-Que, a roadside joint straight out of central casting complete with hound dogs in the yard, picnic tables inside, racks of pork rinds and jerky, and a counter full of large jars of Kool-Aid pickles and pickled pigs’ lips. The barbecue was sublime: sweet and tangy with a slight char. And it was only fifteen minutes from Oxford. Replete with ’cue and beer, we found our way into town. A false turn meant that we missed the entrance to the University of Mississippi campus and ended up at the town square. Ever vigilant for shopping opportunities, I spotted an antique store called Material Culture. An hour later we emerged, I with a boxed set of bone-handled silverware, a nineteenth-century overshot blanket, and friends who have endured for more than twenty-five years. The square also boasted a world-class bookstore, and as I am one who owns upwards of six thousand books, that was worth the trip in itself. Mississippi was not at all as I had imagined it; it was confusing, problematic, and powerful.

With the passing years, as in the 1967 film Two for the Road, I recalled earlier journeys as I sped down the stretch of asphalt with different drivers and cohorts of changing and developing friends. It was always the same road, and yet it was always different. Sometimes it felt as if I passed incarnations of my younger self. A stop at Cozy Corner barbecue restaurant in Memphis stood in for Betty Davis some years. The barbecued Cornish game hen was well worth a stop, not that far from the Memphis airport. I rarely entered Oxford without a bag dripping grease from some barbecue joint and always had an armful of that purloined cotton.

In later years, after I stopped attending the SFA annual symposium, my Mississippi journeys continued to morph. I no longer headed to Oxford but often bypassed it to take other turns and roadways all the way down to Greenville, where for about five years I regularly attended the Delta Hot Tamale Festival held there the third weekend in October. For many of these trips, my driver and companion of the road was Oxford legend Ron Shapiro, a.k.a. Ronzo. With him, I discovered other ways out of Memphis, other places to eat, and other roads because the trip to Greenville took me into the Delta and to another storied part of the state.

The friends on the Oxford jaunts were culinary, but the Delta Hot Tamale Festival, curated by the late Julia Reed, was a bonanza of writers and artists. I got to share rides with legends like Calvin “Bud” Trillin and the artists William Dunlap, John Alexander, and Ashley Pridmore. One year, we took a page from another Dylan song and revisited Highway 61. As we journeyed along, we took a detour to Greenwood, where we stumbled on a blues festival and the town’s artistic vibe made shopping even more fun. I left Greenwood with an antique cotton-picking basket to remind me of the not-so-distant past and a Mose T painting of a watermelon. We stopped at the crossroads of Highways 61 and 49 in Clarksdale near the spot where bluesman Robert Johnson allegedly made his deal with the devil. On other trips we visited spots that sang with the poetry of place: Itta Bena; Indianola and the B. B. King Museum; Leland, the birthplace of Kermit the Frog; Sunflower County, home of Fannie Lou Hamer; and Alligator.

Road trips in Mississippi always left me seriously conscious of my personal cultural conundrum and constantly aware that the bright adventure-filled names all too often covered places where life’s promise for folks like me was the grease smear of roadkill on a country highway. Yet through it all Mississippi fascinated and still fascinates me, and I can’t wait to see what will turn up on my next ramble.