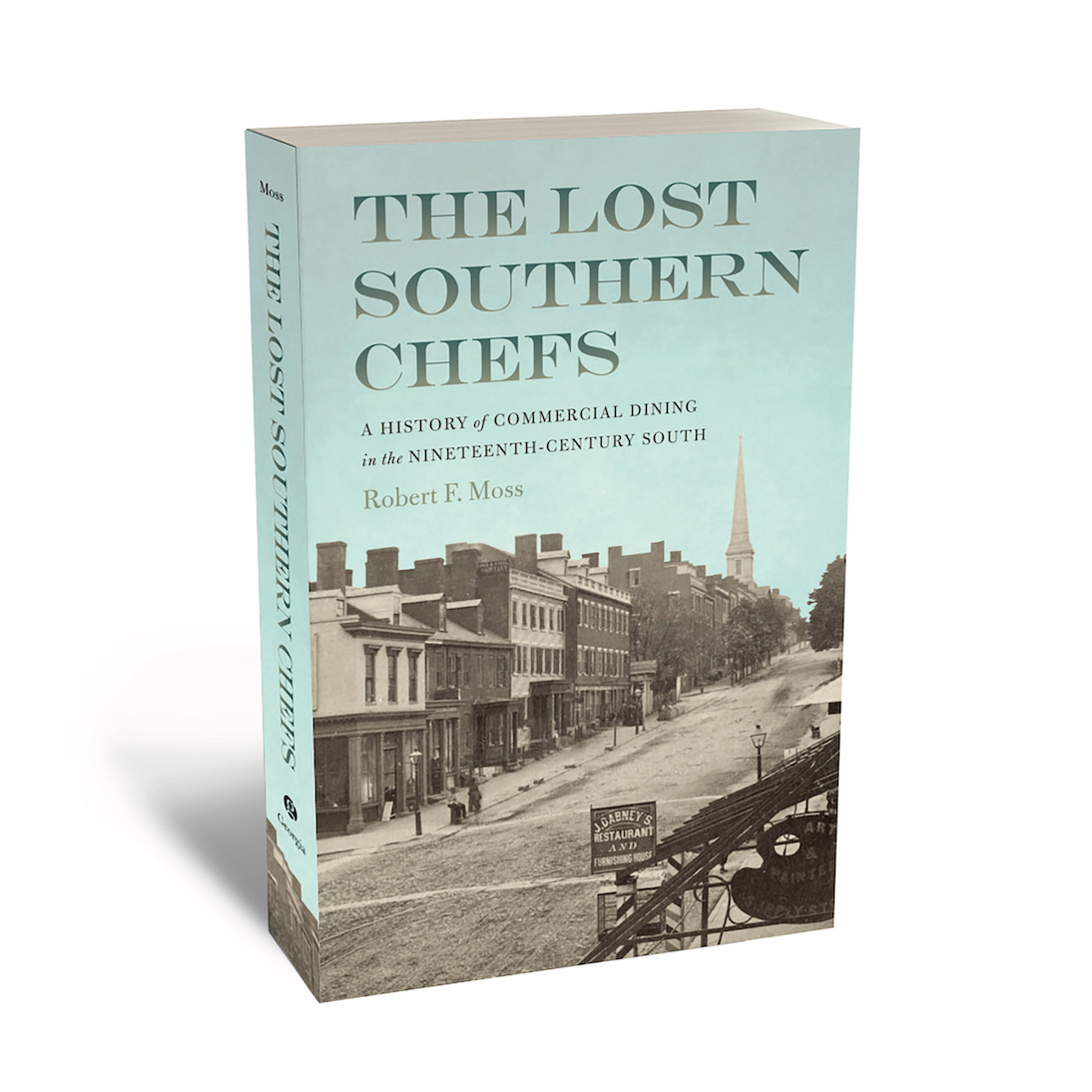

Southern cooking, like midwifing and needlecraft, has generally been considered one of the home arts. We’ve tended to picture its originators and chief practitioners as women—Black, white, or Native—in rural kitchens, simmering and stirring what would become the Southern culinary canon: fried chicken, grits, field peas, cornbread, greens. And for the most part, this is true. But as the food and drink historian Robert F. Moss explores, in The Lost Southern Chefs, a parallel mode of cooking and eating also developed in the nineteenth century. In restaurants, saloons, hotels, and banquet halls, a variegated troupe of chefs—back then known as caterers—were fashioning another genus of Southern cuisine boasting a distinctive flavor profile: broiled shad, terrapin stew, green turtle soup, canvasback duck, Madeira wine, and Lynnhaven oysters. Their work, Moss writes, “elevated southern cooking to the ranks of high art,” influencing menus and dining trends across the nation. It has also largely been forgotten.

“Those caterers,” writes Moss, “are central characters in one of the great untold stories of the South’s cultural past, a story that is very different from the more familiar one about daily cooking on plantations or in family kitchens.” The Lost Southern Chefs is Moss’s effort to exhume this buried history and to restore, at times painstakingly, the legacies of these chefs.

First, he has to clear a few cobwebs out of the way. Among them, the perception that nineteenth-century restaurant fare was, in Moss’s words, “very, very bad, and…especially bad in the South.” Charles Dickens gave said fare a famously swift kick in his novel Martin Chuzzlewit, in which he depicted American boardinghouse food as a nightmare, “great heaps of indigestible matter.” Indeed: Moss quotes a traveler passing through Mississippi in 1861 lamenting a breakfast of “execrable coffee, corn bread, rancid butter, and very dubious meat.” Keep in mind, however, that some travelers in current-day New Orleans opt for dinner not at Commander’s Palace or Domilise’s but at Buffalo Wild Wings; the past’s claim on terrible food is hardly exclusive. “It was actually quite easy,” Moss writes, “for travelers to dine well in Southern cities, provided they had the means.” Moss reprints several menus, including one from an 1860 banquet in Louisville at which guests chose from quail on toast with butter sauce, buffalo tongue with aspic jelly, saddle of Lexington mutton with green crab-apple sauce, and—for an eyebrow-raising riff on surf and turf—broiled squirrels with clam sauce.

Who were these lost Southern chefs, fusing squirrels and clams and, as one Augusta, Georgia, newspaperman slyly reported, adding brandy, mint, and sugar to “water so as to take all the bad tastes out of it”? They were mostly Black men and women, or immigrant entrepreneurs, and “they didn’t advance their craft behind the scenes as nameless hands in the kitchen,” Moss writes. “Instead they were right out in front as hosts, chefs, and business owners”—even, as in the case of Charleston, South Carolina’s Nat Fuller, when they were enslaved. Moss dug into archives to reconstruct the lives of Fuller, the Augusta restaurateur Lexius Henson, and Washington, D.C.’s George T. Downing, among others, and interposes those with lively dining histories of cities like Richmond and Baltimore. “Contrary to myths…the driving force behind southern restaurants wasn’t ‘old mammies’ who cooked by mystical instinct under the tutelage of white mistresses,” Moss writes. “That cuisine instead was created by a remarkable cast of talented and determined men and women who navigated a complex web of social conventions and legal restrictions to achieve commercial success as professional cooks and caterers. Some even got rich doing it.”

For a while, anyway. We see the demise coming as the bright promise of Reconstruction devolves into the ugliness of Jim Crow. “Their restaurants were shuttered, their stoves and ovens removed, their buildings eventually taken apart brick by brick or brought down by the wrecking ball,” Moss writes. “Their signature dishes were forgotten, supplanted by new waves of French and Continental fashion. Few of these chefs’ recipes were written down or made their way into cookbooks, so their methods and techniques were lost, too.” Many of their prize ingredients also vanished, after decades of market hunting, overfishing, and the befouling of ecosystems. But just as oysters are slowly being restored in Virginia’s Lynnhaven River, so too may Moss’s lost chefs—and their delicious, complex legacies—be returned to our culinary history.