The World’s Tiniest Bird Dog arrived December 1974, in the wriggling toe of a Christmas stocking. Dad laid the glittering red-felt pouch beside the hearth, and out tumbled a fur ball the color of a Hershey’s Kiss and only slightly bigger. Along with our heaps of toys, here was a toy poodle. I’d never seen a dog small enough to perch on a man’s palm, literally. As my father cupped the sniveling brown powder puff, none of us could have imagined the pup was meant for anything but lap naps.

We named him Tom—Thomas Thumb Ward. To my eight-year-old ears, Tom seemed as good a name as any for a dog, though I came to realize both moniker and dog were eccentric. Our upstate South Carolina neighbors had more conventional canine companions: Princess, a boxer who greeted visitors with overjoyed snuffles, a clatter of claws on hardwood, and kidney-bean twists; and a gray-bearded black lab named Blue, an old gun dog who roamed the wooded lots until his master, a private man who worked for the forestry department or maybe Fish and Game, bellowed him home: “Heyyyyyy, Bloo! C’monnnn, Bloo!”

Like most small-town doctors’ wives back then, my mother played tennis. There were always tennis balls bumping around our station wagon’s way-back or gathering dust bunnies in utility-closet corners. Though none of us remembers the first fetch, at some point during his early development, when his mouth was big enough, Tom plopped a felt-covered orb at our feet and whimpered. Thus commenced Ball Fever.

Tom’s exploits began in the TV room. He was an indoor dog, after all, small, not a shedder. As my brother, Bill, and I whiled away hours in front of the boob tube, we sent Tom scampering, bouncing tennis balls off walls, arcing them behind the sofa, flinging them under chairs, and ricocheting them down the hall and into the dining room.

Tom’s tennis-ball obsession became a parlor trick. We invited friends. Come watch the tiny poodle fetch balls bigger than his head! Soon the panting expectancy, yipping, and dropping and redropping of balls into laps grew tiresome. We tucked Tom’s ball inside cabinets, atop the mantel, or behind books lining a tall built-in shelf. Tom was no quitter. He’d hop like a mountain goat from floor to chair to shelf, or paw at a couch cushion as if he were digging a hole until we feared he might.

No house could hold Tom, lapdog or not. Our games of fetch moved outdoors. I’d pump my arm, faking a throw, and while Tom sprang off in that direction, I’d spin around and hurl the ball into the woods or distant azaleas. But it was just a matter of time before Tom trotted back, head held high, not out of pride but to balance the heavy ball.

Our dad thought it only natural to take his little “Tom Tom” on a dove shoot. Centuries ago, large poodles were bred to hunt, but their reputation took a U-turn after they became coiffed and pampered pets of the French royal court. More than a century ago, W. R. Furness wrote in The American Book of the Dog that if you accused a dog man of owning a poodle, “he repudiated the charge immediately, and felt deeply insulted, as these dogs were deemed fit only for the circus or for mountebanks.”

After one hunt, as we cleaned birds over newspapers in the garage, Dad pulled a dove from the pile, gave Tom a whiff, and tossed it into the woods. A brown blur shot after it, the tiny form swallowed up by the underbrush. We heard rustling and then nothing. The tennis ball would be back in thirty seconds flat. We waited.

“Fetch, Tom!” Dad hollered. Nothing. “Tom Tom!” he said through clenched teeth, “get your little butt back here!”

Tom pranced back with a face covered in feathers, licking like mad to remove them.

“He was all juiced up,” Bill remembers. “That dove did something to Tom. He went cuckoo over it.”

After that, Dad gutted a dove and stuffed the breast with cotton, lacing it up again with needle and thread and storing it in the crisper drawer of an old beer fridge. After a long day at the hospital, he’d stand in the driveway, firing blank rounds from a starter pistol while tossing the fleshy trainer. Time after time, Tom wobbled back, head sagging, mouth stuffed with bird, struggling to see over the feathers.

That diminutive dog was a quick study, and one day Dad, in his eagerness, decided Tom was ready for a field trial. And why not? Though half as big as a house cat and hardly heavier than a mallard (which made duck hunting out of the question), Tom had the right stuff, even if he occasionally had to stop, drop his quarry, and rest. Size wasn’t really the issue, though, at least not for me. Privately, I wondered if we—more pointedly, if I—could handle the embarrassment of entering a dove field trailed by a pint-size poodle.

In the field, we discovered another problem. We had driven a dozen miles to an old dirt farm Dad had bought for weekend dabbling. The land was long fallow, so birds were scarce, but we packed the stuffed trainer in a cooler full of cold drinks. Tom ignored the shotgun blasts and went straight to work, bounding through weedy thatch and reemerging minutes later with a big gray bird in place of his head. The problem was cockle-burs. With every pass, those curly locks snatched up the spiky seed pods, which worked themselves deep into his long, fine hairs. Pulling cockleburs off your tube socks is one thing. Back home, Tom squirmed and our fingers bled as we picked the burrs one by one out of his matted coat.

What Tom needed, Dad decided, was a hunting suit. This was not the most practical solution. Dog apparel was only beginning to catch on. True, the trendsetting Tom owned a navy-blue crewneck sweater, but I doubt there was a store in the world that sold a poodle hunting suit, at least not in Tom’s size.

Undaunted, my dad got his hands on several yards of beige Ultrasuede and tracked down a seamstress willing to custom-tailor the tiny ensemble. Ultrasuede—the world’s first synthetic microfiber—was all the rage, at least among the ladies of our mill town. They bought deeply discounted yards of it straight from the plant. My mother proudly wore the forest-green Ultrasuede vest she had made to Ladies Auxiliary luncheons and other dress-up affairs. Tom was less enthusiastic about his getup. The design was fairly ingenious, a bit like today’s canine saddle coat but with leggings that tapered into fitted booties. A brimless cap made from the same beige Ultrasuede tucked around his head and fastened below the throat. The struggle to dress him must have seemed to Tom like some strange new torture. The only part he could not abide were the built-in booties. Dad knew to pick his battles and snipped them off just below the dewclaw.

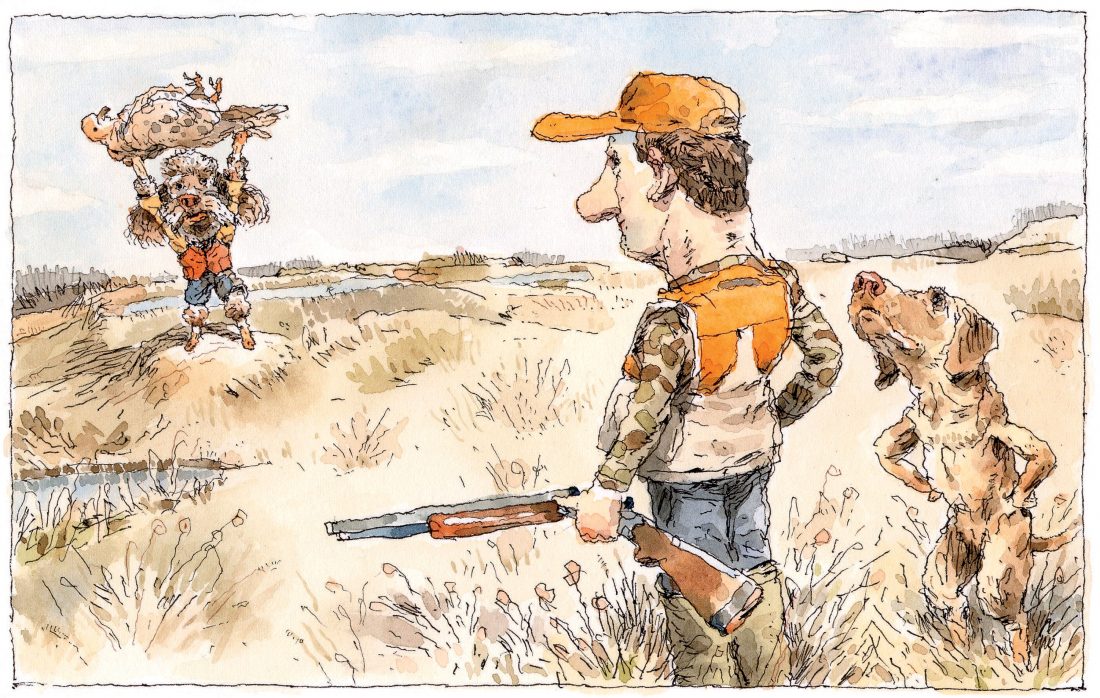

On the morning of Tom’s first public hunt, Dad steered off the blacktop, and we jounced toward the edge of a stubbly cornfield, where a clump of camo-clad men and boys and their dogs were about to meet Tom, a perky poodle dressed like Oliver Twist in knickers and newsboy cap.

“Hey, look at that little dog!” a man said as we approached, lugging dove stools heavy with #8 shot. “What are you gonna do with that thing?”

“We’re going to hunt,” Dad said.

“With that sissy dog?” he asked. Other men laughed.

“Don’t you worry about this little dog,” Dad said. “You’ll see.”

The chatter continued, but soon we split up and spread out around the field’s perimeter in search of cover. Tom, hyper by nature, darted off. “Tom Tom!” Dad called. He returned but kept weaving around, sniffing things and yapping at the black Labs and spaniels. Tom could retrieve, but could he heel?

He could not. Still, between Dad’s clenched-teeth rebukes and Bill and I snatching him up whenever he scooted past our stand of cornstalks, the three of us managed to keep Tom under control. The gun blasts helped focus his attention.

The rate of incoming birds picked up. Dad fired at an approaching trio, and one fell, landing nearby. He pointed and spoke—“Back!”—and Tom zigged and zagged after it, his Ultrasuede suit rustling the corn stubble. When he returned, bird in mouth, I relaxed a bit, though the man who had branded Tom a sissy hadn’t noticed.

Tom got another chance to prove himself. Though I don’t remember the details, according to my father, who is now eighty, the same man downed three doves in quick succession. Tom slipped our grasp and bolted toward the place where they fell. As he wobbled back to us under the weight of a bloody dove, the man poked his head above his cover and yelled, “That dog’s taking my bird!”

“He’s a bird dog,” Dad said. “Don’t worry. You’ll get it back.”

Tom fetched the man’s other two doves, and later, as we stood beside the vehicles sucking down cans of Mountain Dew, Tom lapping water from my brother’s outstretched palm, the man approached. “Doggone if you weren’t right,” he said as Dad handed him his birds.

With the hunt over, the beer-sipping men made a fuss over Tom’s performance, though I doubt any of them were sold on the idea. To them, he was a novelty.

In all honesty, they were right. If Tom’s story were a Disney movie script, he might beat one pedigreed pointer after another to win the National Field Trial Championship. But Dad wasn’t looking for a champion. Had he been that committed to the sport, we never would have owned a toy poodle in the first place.

Tom continued to join us on hunts—never learning to heel but always sparking conversation—but he seemed just as content scrabbling across the den floor to fetch his smelly tennis ball. His final years were even more un-Disneylike. His hair thinned, and his breath grew rancid from teeth so infected the vet had to pull them all, causing his tongue to loll out of the left side of his mouth.

I lost touch with Tom when I went off to college. As his time grew short, he remained as sociable as always, even without his teeth. “The day before Tom died we had people over, and he was right there in the middle of it all,” Dad recalls.

Today, we live in an age of numbers, of so-called Big Data. I hold no quantitative proof that Tom was the World’s Tiniest Bird Dog. Does it really matter? He was small, and that dog did hunt.