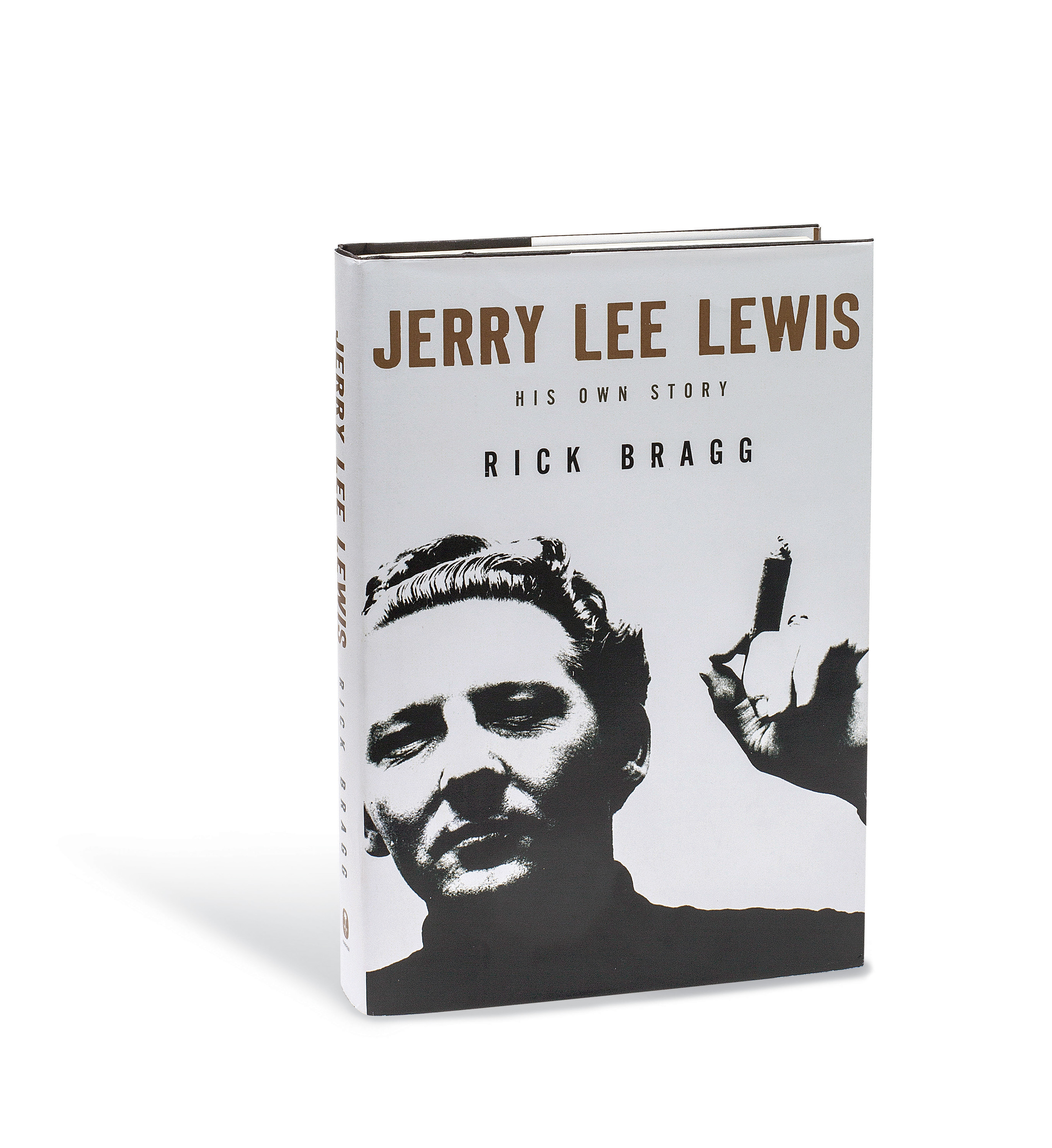

Artists

Jerry Lee and Me

When the call came to write Jerry Lee Lewis’s biography, Rick Bragg knew he couldn’t say no

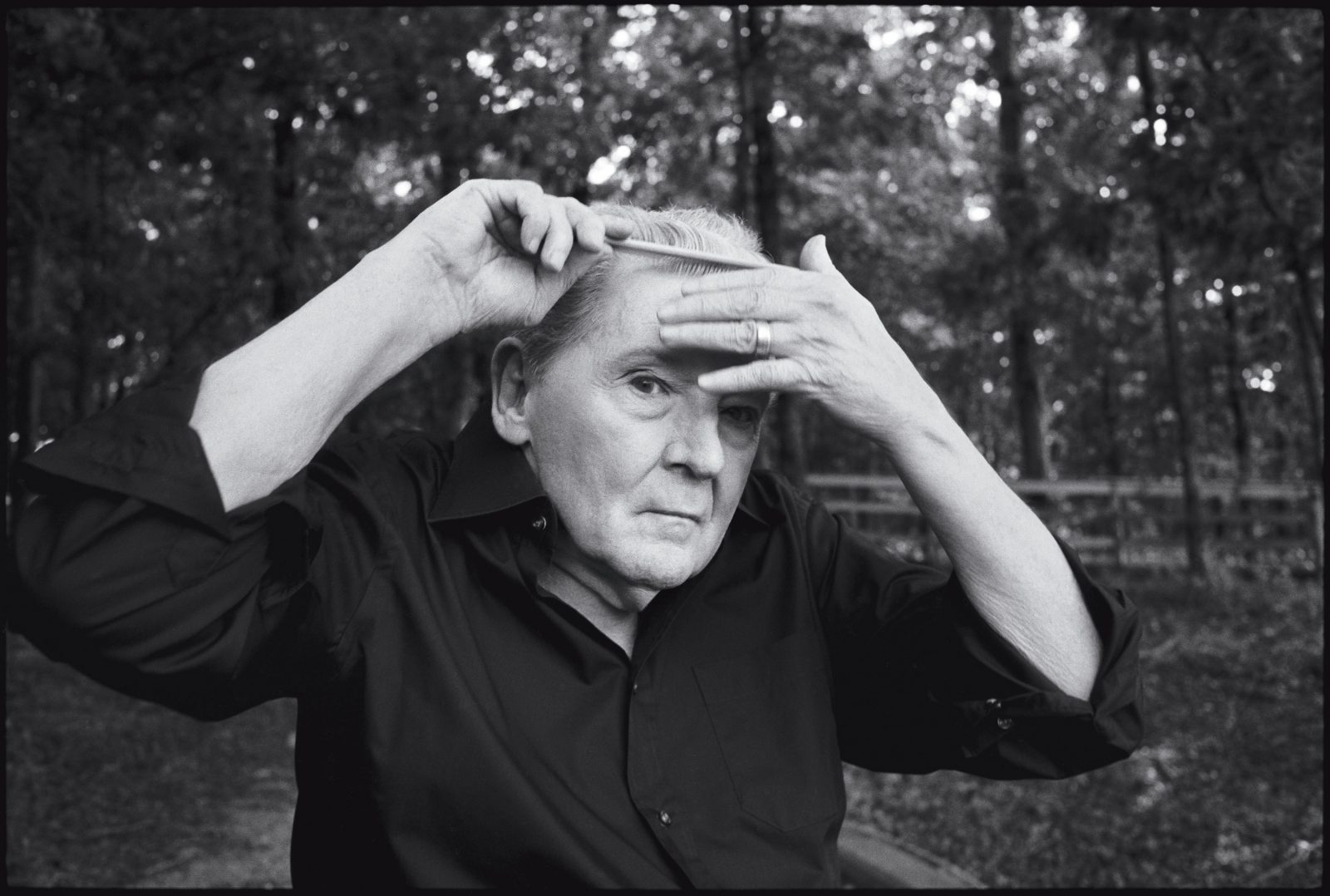

Photo: Jim Herrington

Lewis in classic form.

Over the course of two years, Rick Bragg visited Jerry Lee Lewis in his bullet-hole-ridden, memorabilia-strewn Nesbit, Mississippi, home—their conversations ranging from Southern mamas to Elvis to religion to death. Here, Bragg recounts his time with the man they call the Killer.

The big cat’s dead, glass eyes glared up from the floor.

“That’s Jane,” the rock-and-roll singer said from his comfortable chair.

The cat, a mountain lion, had been reduced to a tawny rug on the floor of the den, and now snarled, silently, from beneath the big black grand piano. The rock-and-roll singer had named it—the rug, not the piano—for his second wife, a hellish woman who was hard on a windshield, who went at him and his vehicles with Coke bottles, and claw hammers, and flying Santa Claus figurines.

“Knocked me down the stairs one time,” he said.

He thought on that a while.

But then, a lot of women did.

“One time, this woman hit me right in the forehead with the pointy heel…Atlanta…I believe it was the seventies…Blood went ever’where…Had to stitch me up…”

I asked him if he deserved it.

He tried to recall, but it was lost, somewhere.

“I’m sure I did…for somethin’…somebody…”

He nodded at the dead eyes of the lion.

“Ain’t that right, Jane?”

Of course, it was going to be a long, strange trip. I knew that when I picked up the phone, about three years ago.

New York was on the line. Little stuff never rolls down from New York; that city does not do piddling. It is my imagination, surely, but I’d swear that receiver felt warm in my hand.

“Do you have any interest in doing a book on Jerry Lee Lewis?” my agent asked.

A cautious man, a deliberate man, would have carefully considered this, and gone and hid under the bed.

He learned the piano in his hometown of Ferriday, Louisiana, but Memphis had been the launch of his stardom, there under the nicotine-stained acoustic tiles at Sun Studio. He still lives just a few minutes down Interstate 55, down the Delta, not far from the big river in northern Mississippi. He was born in the bottomland. It is where he will end. On the way to his house, I passed a dead armadillo; armadillos die ugly. I had read somewhere, in one of the million or so stories told about him, that he was haunted by armadillos, which are said to feed in the low country graves. But people say a lot of things, believe a lot of things, when a man’s legend swells beyond the scope of normal people and normal things, as if everything about a man has to have some degree of dark magic in it, even roadkill.

It was hot that first afternoon, hot for all the weeks to come, as if the dog days had settled hard on DeSoto County and stuck like flies on the lid of a jelly jar. The big iron gates—the ones with a piano on them—swung open from the middle, creaking and shuddering like something from a scary movie. I drove up to the big brick ranch-style house, built on the edge of a man-made lake. I had interviewed a million people, but not a legend before, not the living history of rock and roll, not one of the last true troubadours.

“A driving blues shouter…taking off like wildfire…phenomenal,” lauded Billboard, in its Pop, Country & Western, and Rhythm & Blues sections in 1957. Writer Jim Jerome called his voice “a laser of grief” in People in 1978. In Esquire in 1982, Mark Humphrey wrote: “If you think a redneck can’t sing the blues, just listen to him belt out ‘Big Legged Woman,’ or ‘Sick and Tired.’ If you think he’s always a snide bastard without a redeeming trace of sincerity, listen to his moving rendition of the gospel standard ‘Will the Circle Be Unbroken.’ And if you think anything about the man can be neatly pigeonholed, think again.” The words themselves were not often poetry, but poetry is hard to dance to. It is how you sing it, pound it, that matters, or you might as well read it off a post office bulletin board or the bathroom wall. People called it genius, and he became a man you made exceptions for, to hear him do his thing.

In his hometown, in a rambling museum crammed with memorabilia, I knew, there was one of the many grand pianos he had played over a career that spanned six decades or more. He rarely walked in a room with a piano he did not, at some point, take over by divine right. Even Elvis, the first time they met, surrendered the piano to him. Still, visitors to the museum ask. Did Jerry Lee play that one, that very one? And his sister Frankie Jean, the curator of the museum, just sighs. “Well, I guess he did,” she tells them. “He played every one in the world.” But wrapped around the genius, weaving through it, was such death and suffering as to be medieval. What was left of him? I wondered as I opened my car door.

Photo: Jim Herrington

"He Played Every One In The World"

The Starck upright on which Lewis learned to play piano; when he was ten, his parents mortgaged their farm to buy it.

I was set upon by a small pack of dogs, each one a different breed from the other. I was reassured by the people who looked after the man that they did not usually bite—well, all but one. His name was Topaz, Jr., and he was about the size of a squirrel monkey. His sire, Topaz, was an old dog and lay near death, and Jerry Lee Lewis grieved. Like a lot of people who have left a certain amount of human carnage in their wake, his heart broke over a dog, or over an animal of any kind. His friends love to tell of the time he saw a donkey painted to look like a zebra down in a Mexican border town, and, pretty well drunk, wanted to put it in the car and take it home with him to Memphis, take it away from all the craziness, fireworks, and tequila. He was not altogether convinced it wasn’t a zebra, but whether it was or not his friends talked him out of it, though that donkey/zebra stayed on his mind a good long time.

RELATED: HEAR RICK BRAGG’S FAVORITE JERRY LEE LEWIS SONGS

I knocked on his bedroom door, reinforced by iron bars. He lay there in the gloom, bullet holes in the walls, a rummage sale of memories stacked on the shelves and on the walls; there would have been more, but the IRS had raided him across the years. Hank Williams, his photograph draped with a black ribbon as if the man in the bed was still in mourning, looked down on me from the edge of a chifforobe. The man himself, even in pain from a half dozen ailments, was still handsome, his hair still thick and wavy but silver now, no longer that burnished gold that had made even the church ladies feel a little funny during “Great Speckled Bird.”

“Never did see him…play for him,” he said of Williams, and it seemed so odd to hear regret in that man’s voice that I actually wrote the word—REGRET?—in big letters on my legal pad. He did just about everything else in his life he ever wanted to do, did some of it almost perfectly, most of it wildly and with feeling, and some of it…well, he had a good time in the chaos, doing that, too. He was only seventy-seven then, but seventy-seven for Jerry Lee Lewis is like being seventy-seven in dog years. Still, all the pills and whiskey and needles and more, from all those nights on and off stage, had only laid him up, not put him down. The jealous husbands had not left a mark on him, after so much time.

“I’m still here,” he told me, as if reading my mind.

“Yes, sir,” I told him.

But they’ve had your obit written, I thought, for quite some time.

He is done with all the mess now; he is immersed in clean and righteous living. He is still Jerry Lee Lewis, though, not able to leap to the lid of his grand piano but still able to make it ring with honky-tonk, blues, gospel, all the genres he had helped weld into rock and roll, so long ago, when the music rose up from a little storefront studio on Union Avenue and swept like a storm across the country and the wider world. He had conjured that, him and Elvis and the great Chuck Berry and the rest, and he is not done yet. He is still recording; his last two CDs were his best-selling collections, ever. Bruce Springsteen sang backup on “Pink Cadillac.” Think about it. Like I said, it can be tricky, with legends.

I have been doing this stuff a pretty good while, taking people’s memories, making something from them that is more than just a window dressing of life. I have come to believe it is best to just talk a while across some common ground. But music is his life and I am no expert; I could not play a comb and tissue paper, and in second grade had been asked to hand in my kazoo. But we both loved our mothers, me and him. He would even change the words of his songs, to sing about it. One song had haunted me, one he did in the Memphis years. I could not talk the Yankee editor into putting it in the book, but it almost made me cry.

Can you really rock and roll, Billy Boy, Billy Boy?

Can you really rock and roll, charming Billy?

Yes I can really rock and roll, I can even do the stroll

But I’m a young cat, and I can’t leave my mother.

So we began with that, with the woman who brought him cocoa and vanilla wafers for breakfast in bed, but, when he fell hard from grace and fame, had been a steel rod driven through him and into the earth itself. He could not have lain down and died, quit, if he wanted, not with that woman standing there to remind him he was her blood, too. And so we talked about mamas, and biscuits, and sometimes the ringing, stinging flat of their hands. People said his mama was ashamed he played the devil’s music, “but that was bull,” he said, hotly. His mama sat alone as her hard-drinking husband served time for bootlegging, survived the death of a precious child, dragged a cotton sack. What would have shamed her, he said, was to accept defeat in a time when people were saying such mean things about her boy. Once we got that straight, the rest was easier. Sometimes a romantic notion is just that, a theme. It was hard to bind together a theme in his life, like trying to take a thousand lightning bugs dancing in a field, and mash them together in one beam of light. But I know he meant it, when he talked of loving her.

Photo: Jim Herrington

"I'm Still Here"

Lewis at his Nesbit, Mississippi, home.

I know because, as my own mother lay on an operating room gurney in Alabama, as I fretted in the waiting room with my big brother as a surgeon put a stent in her heart, my phone rang. It was the Killer speaking.

“How is your mother?” he asked.

I told him she had been so tired, lately.

“Well, you tell her it might not be her heart,” he said. Sometimes, he said, it can be hard to carry around all those years. “Jerry Lee Lewis asked about you, and wished you well,” I told her later, in recovery, but she was on some pretty good drugs right then, and I could have told her it was John the Baptist’s head. Still, it meant a lot to me.

Over the weeks we talked about heaven, and hell, how he was trapped between a religion that was preached so hard a man could hardly live it, and a life of temptation so dark, so delicious, a superman could hardly resist. Most people have to choose, here in the South; they just don’t have quite so much to pray away. As the weeks went by, he told me stories about honky-tonk fights and pharmaceuticals and passed-out airplane pilots, and shooting false teeth off the wall of a dentist’s office. He rarely got mad at me even when I had to ask him some harsh questions, questions about his drug use, his women; and I had to ask mind-breaking ones, about the coffins that had passed him by, including those of two sons. I had read he once shot a bass player, more or less accidentally. One afternoon, he showed me a brushed-steel .357, but he was not mad at me at the time and, me being a Southern boy myself, I think he thought I would just enjoy seeing it, the way other people might show off a Matisse, or a Ming vase. He kept it under a pillow, “in case somebody bothers me,” he said, and smiled at me. I smiled back, but on the way out the door I realized he had not meant to shoot the bass player, either, and he bled all over the white shag carpeting.

He was not in good health when we began, and would, over the next few years, swing close to death more than once, with pneumonia and shattered bones threatening him, and arthritis causing him unrelenting pain, and I was, frankly, afraid my book might be written after he—probably snarling like that rug—left this world. But that was old hat, for Jerry Lee. Doctors had told him, to his face, that he was going to die, to prepare himself for his Maker, and that was before he got old. In two years’ time, from when we began the interviews, he was not only recording again but playing in Europe.

Once, thinking about death, he raised his hands to his face and spread the fingers out.

Time has not touched them at all.

Spooky.

At the end of the day, as we neared completion of the interviews, his caretaker, Judith, would give me some good iced tea in a Tupperware glass, in a kitchen that smelled of cooking vegetables, potatoes and green beans, and stew. They would be married, in time, his seventh. Judith had been married to his cousin and ex-wife Myra’s brother, and if that seems somehow complicated to you, you have obviously not followed his life at all. Jimmy Swaggart is his double first cousin; his bass player—the one he did not shoot—was his cousin and father-in-law. It gets better.

Most people know some of it, how his daddy, Elmo, mortgaged the farm to buy the boy a piano, and how he beat it like it stole somethin’, beat it with pure genius, mixing the music of the Assembly of God with juke-joint blues and hillbilly music and everything; how he went to Sam Phillips—the man who found Elvis—and rode rock-and-roll music to the moon, man, music like “Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On.” They have heard how Elvis, drafted into the army, went to Jerry Lee and surrendered his crown, and wept. “I’s gonna take it anyway,” Jerry Lee said. But then his marriage to his thirteen-year-old cousin, Myra, blew up all over the newspapers, and he fell, on fire, into mean little beer joints and no-tell motels, playing some big dates, still, but not like it was. But he refused to vanish, and played and played, because if you have a talent like his you do not leave it staked down in the yard like some forgotten dog, and in the 1970s he went pure, hard country, and made more money than Standard Oil. He partied himself to the edge of death, two times, three times, more. Along the way, he crashed a hundred Cadillacs, a dozen Corvettes, flipped a Rolls-Royce or two, and rammed the gate at Graceland going to see his buddy, not intending any harm, just misgauging the length of a Lincoln Continental’s front end. People threw their hands in the air and squealed that he had come to kill the King. “Ridiculous,” he growled.

It does puzzle him, how that mystery train rolled on and on. One of his keepsakes is the black-and-white photograph Million-Dollar Quartet, taken when Johnny Cash, Carl Perkins, Elvis Presley, and a still relatively unknown Jerry Lee Lewis came together at Sun Studio in Memphis on December 4, 1956. It shows four young men gathered around a piano, singing songs from the radio, from their childhood, and from church. But only Elvis and Jerry Lee, raised in the Assembly of God, lingered for long after the picture was taken. “Johnny and Carl didn’t really know the words…they was Baptists,” he said, and therefore deprived. He and Elvis sat on the bench together, singing, talking into the afternoon. They were good friends, once, bound by a common delight, of being part of a thing so glorious as rock and roll, and by a common dread, whether or not a man can play rock music and not be consumed, in the end, in a lake of fire.

Photo: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

"We Was Legends"

Lewis with Carl Perkins, Elvis Presley, and Johnny Cash at Sun Studio in 1956. "No one wanted to follow Jerry Lee," Cash later wrote of the session, "not even Elvis."

That photograph of the four young men would become one of the iconic images of American music, and a source of great irony. “If you’d asked one of us, asked anybody, ‘Who’s gonna be the first of all of us to die?’ the answer would’ve been, ‘It’s gonna be Jerry Lee Lewis,’” he said.

Now there is only him to speak of the creation, only him, with wheelchair-bound Little Richard and a frail Chuck Berry and reclusive Fats Domino, to shout of the birth of rock and roll. “Daddy took after Chuck one time with a barlow knife,” he said, never claiming memory is a neat and tidy thing. He fought Carl Perkins across the trunk of a ’57 Buick. He watched Johnny Cash steal a motel TV.

“We was legends,” he said of those early days. “We was legends, an’ we didn’t even know it.”

I would forget that, sometimes, sitting next to the man’s bed, him talking about how they haven’t made a good car since the ’59 Cadillac, or of pulling corn with his daddy, or his mama’s tomato gravy. I would forget that the words “shake it, baby, shake it” are enshrined in the Library of Congress, that his music is honored in museums and halls of fame. The Beatles, the Rolling Stones, and other legendary performers say he, as much as anyone, lit the fire and showed the way. Some days, he seemed like just a good ol’ boy, a man you could tell a story to, like the time outside a lounge on the Coosa River when you got punched out by a big woman. And you laugh and laugh, because you know that no matter how outrageous a thing is that you might have done, he did it, better or worse, and did more of it, and if he can do all that for all these many years and still be breathing—no, living—then there is hope for all the rest of us. Surely we will live forever.