Over his more-than-fifty-year quest to make world-class cured hams and bacon, Allan Benton has remained a perpetual student, always open to the secrets that salt, smoke, and time have yet to divulge. “Even after five decades, I’m still learning, and there are surprises,” says the famed owner of Benton’s Smoky Mountain Country Hams, in Madisonville, Tennessee. A big one came last summer, when his son Darrell left a successful career as a radiologist and returned to Madisonville to work with his father producing what might be the country’s most praised pork. “I was not expecting that,” Allan says. “I thought he had it made as a doctor. But he’s the happiest I’ve seen him since his childhood.”

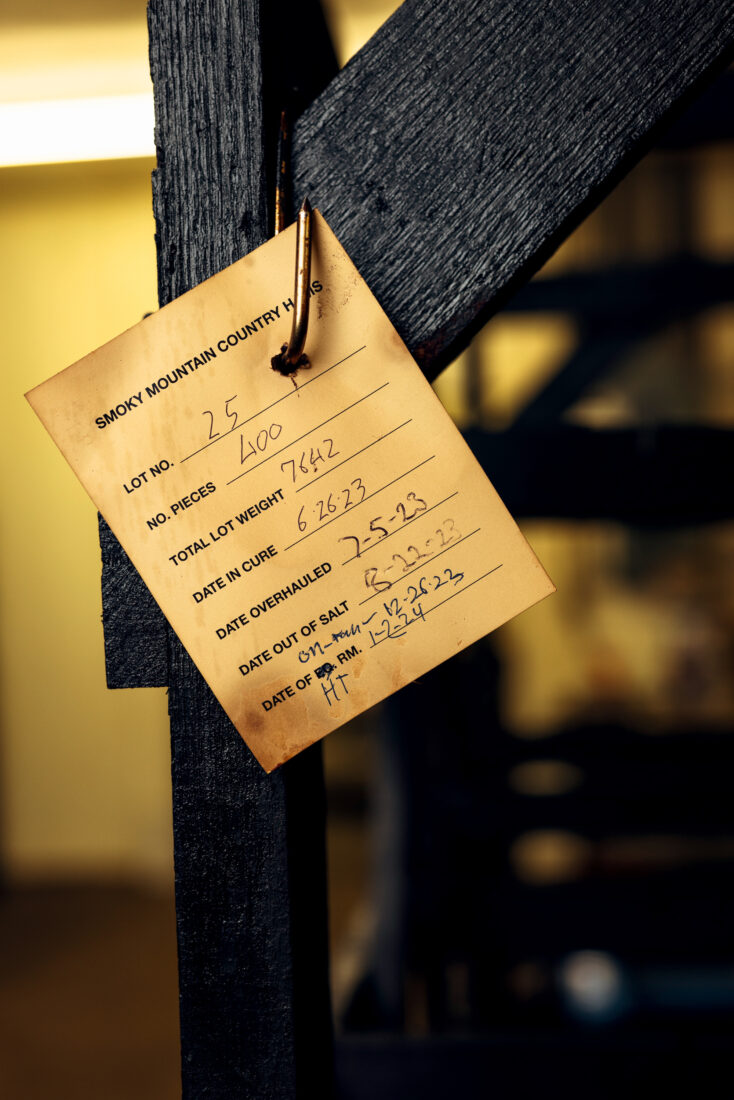

As Darrell walks through the Benton’s facility—housing a shop up front, curing and aging rooms, and two smokehouses—the smile he says he wakes up with stays tattooed to his face. A peek into the dark of a cinder-block building releases roiling clouds that he waves away with a laugh. Even through the hickory scented haze, it’s clear he’s in his element. “Can you smell that?” he asks, weaving through prosciutto-style hams (from pasture-raised hogs) hanging in an aging room, where their flavors concentrate, some for as long as thirty-six months. “Like aged cheeses, these hams are acquiring mold strains specific to this spot in Tennessee. I call this the funkatorium.”

If Darrell’s homecoming surprised his father, he shocked himself, too. “For the first few decades, Dad struggled to keep the lights on,” he says, somberly recalling lean times. “I remember sitting on the old church pew out front, praying someone would come in and buy ham.” He worked at Benton’s after school and during summers, and after college, “I went looking for greener pastures.”

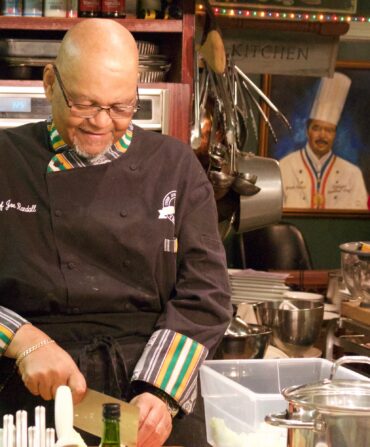

He headed to medical school in 2007, aiming to cure anything but meat. Meanwhile, chefs had begun discovering the ham curer from Madisonville, and the Benton’s name had started appearing on menus at a host of the South’s best restaurants. “It was our salvation,” Allan says. Fans around the region and beyond soon came calling for a taste of his prized hams and ultra-smoky bacon (a fact Allan shrugs off with a soft smile, shifting credit to others, like Albert Hicks, a local dairy farmer and ham curer who mentored him early on). Still, Darrell wasn’t ready to leave his career to bring home the bacon by making bacon.

Then, while he was in residency, memories of the smokehouse began seeping into his consciousness. “I pushed them aside,” he says. “I thought I’d eventually quit dreaming of curing meat.” But a few years into practice in Knoxville, where he spent multiple hours a day alone in a dark room, reading scans, the pull of home won out.

Darrell officially began reporting for work at Benton’s last August, revisiting skills he’d learned growing up and discovering things he’d never known. Now he’s first to arrive and last to leave each day, overseeing operations, scrubbing floors, slicing meat, and managing employees, all to get the eighteen thousand hams and fifty thousand pork bellies Benton’s cures each year out the door. At seventy-six, his dad appreciates the help, but if you think he’s ready to retire, you haven’t met Allan Benton. “I have no interest in playing golf or going fishing,” he says. “This is where I belong.”

Asked if there’s a formal succession plan, Darrell quips, “We’re pretty hillbilly ’round here. There’s no official document. I am the succession plan.” Following in his father’s humble but heavy footsteps, he says he’s committed to the time-honored traditions that have earned Benton’s its ardent fans—while helping forge new paths, too. Later this year, he and Allan will travel together on a research trip to Italy and Spain to explore local cured-meat methods. “I’d like to experiment with other types of charcuterie,” Darrell says. “I love the continual learning.” And though days in Madisonville keep him plenty busy, so far, he hasn’t been pining for the X-ray room.

“I knew I wanted to come home, but I had no idea I’d love it like I do,” he says. “I’m getting more time with Dad and better time with my two young kids. I work as many or more hours, but I have more control. There’s no such thing as a bacon emergency.”

Jennifer Stewart Kornegay is an award-winning freelance writer and editor based in Montgomery, Alabama. Her articles cover a variety of topics, including food and food culture, makers and travel, but the throughline is an emphasis on telling the stories of the interesting people behind them all.