Kevin Kresse’s home in Little Rock is, by his own admission, somewhere between a “friggin’ Frankenstein lab” and a “Madame Tussaud’s of Arkansas musicians.” Lining the sculptor’s kitchen walls, topping the tables, and squatting on the back porch are the spot-on likenesses of Levon Helm, Al Green, Sister Rosetta Tharpe, Glen Campbell, and Johnny Cash. What started as a 2016 commission to create a bronze bust of Helm, legendary drummer of the Band, eventually became “my own build-it-and-hopefully-they’ll-come project of sculpting Arkansas musicians,” he says.

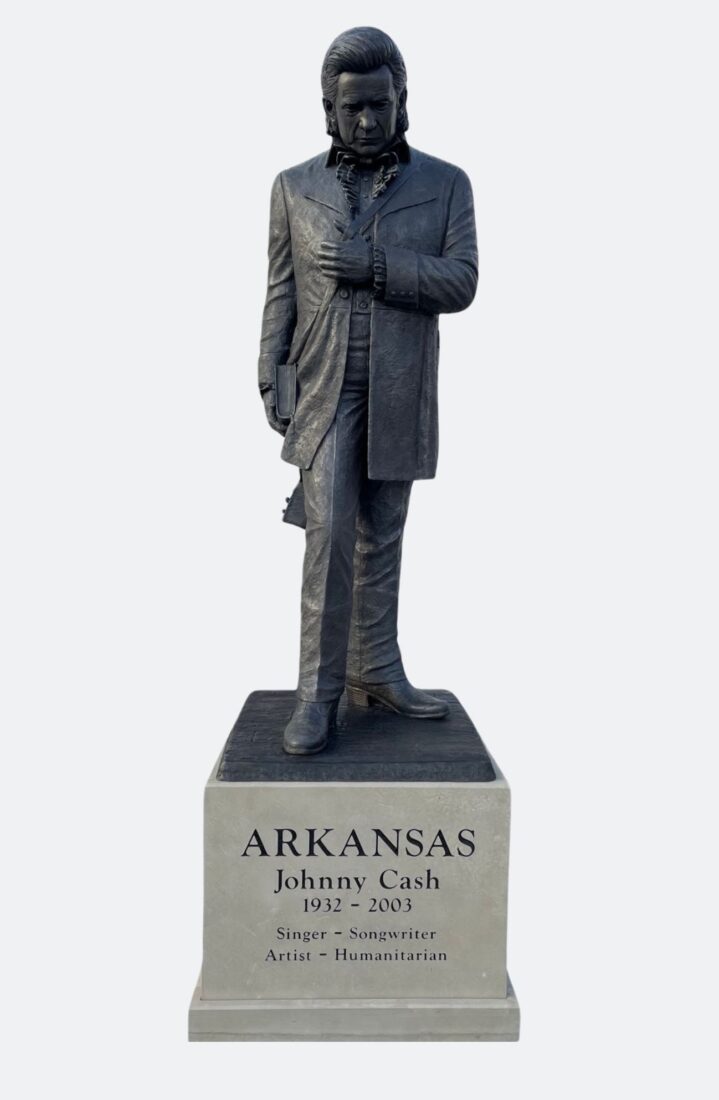

Fortunately for Kresse, he didn’t have to wait long: In April 2019, then-Governor Asa Hutchinson signed a bill into law calling for statues of Cash and civil rights activist Daisy Gatson Bates to replace those of Uriah M. Rose and Governor James P. Clarke in the U.S. Capitol’s National Statuary Hall. After submitting a proposal in 2020, Kresse was chosen to create an eight-foot likeness of Cash—one that was just unveiled today. We spoke with Kresse about the artistic process, what onlookers might miss at first glance, and what it means for Bates and Cash to represent Arkansas on the national stage.

Cash maintained a public presence for the better part of half a century, and there were no doubt countless ways to depict him. How did you decide what version of him to go with?

As my father-in-law would say, “That’s very observatory of you.” During the early seventies, Cash was healthy. He was happy. His son had been born. He was on national television. It was probably his most high-profile time, so that seemed to me to be the right time frame. And then it turned out that the Cash family also wanted that time frame.

But trying to freeze-frame a life story in one pose, one look on the face, you just can’t pack it all in. You know, you do a biopic and you have an hour and a half, two hours, and even then you can’t fit it all in. I have to have a story that I keep in my head. Because you’re making thousands of tiny decisions along the way.

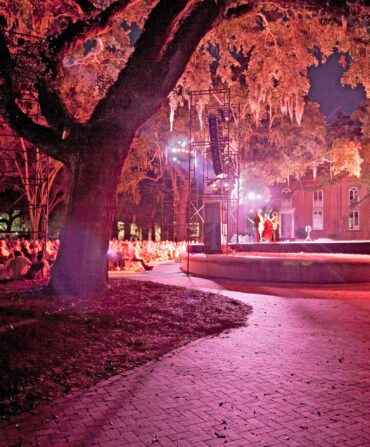

So the story I had in my head was a fantasy story, where Johnny’s come back to play the Johnny Cash Heritage Festival in his hometown of Dyess. He’s gone through the house for the first time since it’s all been restored back to its original condition. He’s had this alone time to go through the house—he’s been reliving all these memories. He picks up the family Bible. He gets ready to walk over to the stage to play, but then he goes out on the porch. He’s looking out at the fields where he and his siblings and his family worked. He’s thinking about his brother, Jack, who was killed. He’s thinking about how his father said it should have been him instead of his brother. He’s just thinking about the highs and the lows of his life—and then he sort of freezes. All of it’s rushing back through him at that point. And so that’s what I had to have in my head as I’m making these things.

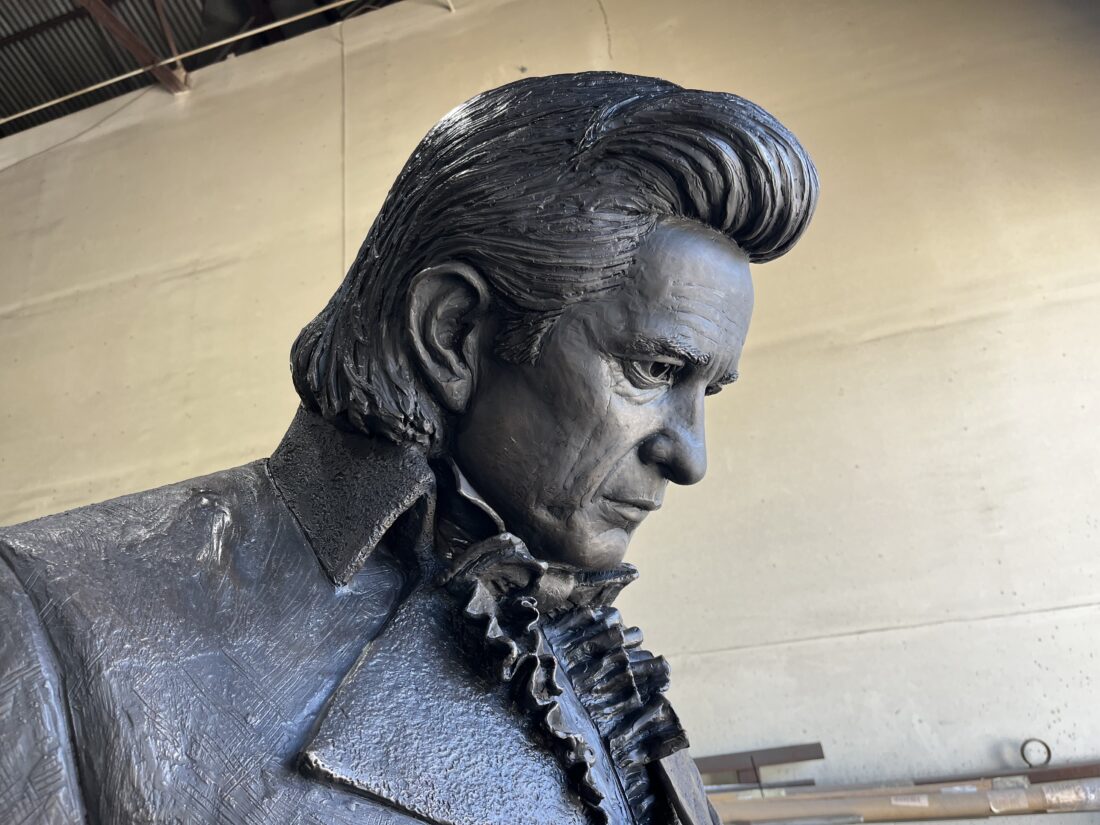

At what point does this raw material effectively “become” Johnny?

It’s a cumulative thing. Through the process of sculpting, I try to keep the eyes closed because it’s too distracting. If you’re working on the head and the face and you’re trying to get bone structure—if someone’s sort of staring at you the whole time, even if it’s in clay, you just want to…You know, as humans, we just kind of look to the eyes. So I try to get it as close as I can with the eyes closed, and then open the eyes. And when I do open the eyes, there is a moment where it feels like it comes alive. And it never fails to thrill me and startle me.

I can’t help but notice that he’s got a Bible…

I remember at first kind of hesitating about putting the Bible in—but I thought, no, it was just such an integral part of who he was, and that’s also why it’s just tucked in close to him. It’s not out in any kind of preacher-y way. During his life, he went down such deep, dark holes. The Bible was what got him out so many times that it seemed to me almost wrong to not include it.

What aren’t people going to see just by looking at the statue?

It was important for me to make [the base] just kind of rough wooden planks to reflect his upbringing in the country, and not be slick and polished granite or anything like that. I didn’t want things to be perfect, especially now with 3D scanning and printing, where you can create a sculpture without an artist touching the piece. I wanted it to have the human feel of not being perfect, that the buttons might be slightly off. And, you know, it has a lot of detail, but it’s not perfect detail.

When we put someone on a pedestal, the whole idea is that there’s sort of a halo over their head, and they never did anything wrong. He was no saint, but that’s what I loved about him. He’d be the very first one to tell you he was no saint. The more I read and watched videos and heard these stories, my respect and love for him just grew.

What’s the significance of Johnny Cash and Daisy Bates being Arkansas’ representatives in the National Statuary Hall—and what does that say about Arkansans today?

As a whole, the Statuary Hall collection tells a story about America through the choices made, and who they want to represent their states. I love that Arkansas chose a social activist and humanitarian. The similarities between [Bates and Cash] are actually kind of striking: They both had rough upbringings, growing up in poverty, dealing with some traumatic events in their childhood. It’s the type of thing where, if both of them had grown up to be bitter adults, people around could point to things and say, “Well, that’s the reason to excuse it.” But the fact that they both ended up standing up for people who’ve been stepped over, overlooked, and pushed to the margins speaks to the character of both of them. Therefore it speaks to the quality of people from this state and America.