On my last big fishing trip with my father, we flew to Alaska to catch a king salmon. It was June, and as the evening sun genuflected toward the horizon, I waded into a river born from a glacier, its waters opaque and luminous, so different from the gentle trout streams I was accustomed to fishing in Georgia and Tennessee. I was pregnant with my first child, but not yet too wide for my waders. Struggling to cast a conventional salmon rod, I studied my father, a seasoned saltwater fisherman, and dreamed of the day he’d teach his future grandson how to fish.

An only child and a tomboy, I was the son my father never had. When his colleagues learned he was having a girl, they posted a sign on his office door: FOR SALE: FOOTBALL, BASEBALL GLOVE, NAILS, SNAILS, PUPPY DOG TAILS. WANTED: SUGAR AND SPICE.

Getting more spice than sugar, he raised me on an Alabama catfish pond, where I learned to drive a boat, cast a spinning rod, and carve a slalom ski. When I was in high school, we lived on a brackish bayou in North Florida, where Dad delivered fatherly lectures on our weathered dock. I grew sea legs on his Boston Whaler as we fished the salty swells of the Gulf. Back then, I didn’t love fishing. It was the price of time with my father.

Getting more spice than sugar, he raised me on an Alabama catfish pond, where I learned to drive a boat, cast a spinning rod, and carve a slalom ski. When I was in high school, we lived on a brackish bayou in North Florida, where Dad delivered fatherly lectures on our weathered dock. I grew sea legs on his Boston Whaler as we fished the salty swells of the Gulf. Back then, I didn’t love fishing. It was the price of time with my father.

I wanted my father to love fly fishing as much as I did. I took him on float trips, booked riverside fishing camps, and hired guides to help us land fish the size he would use for bait. We’d hold them, smiling adoringly, then let them go. Dad pretended to enjoy this, but I could tell his heart wasn’t in it. He was a saltwater meat-pole fisherman. A lifetime member of the catch-and-fillet club.

On our trip to Alaska, in my early thirties, I discovered that salmon are different from any fish we had ever caught in a trout stream or the Gulf. The lives of these anadromous fish are a circular journey. After hatching in river gravel, they spend their first year or two in fresh water, then ride spring snowmelt to the ocean. They travel tailfirst, noses into the current, imprinting smells as indelible as the scent of your grandmother’s kitchen. During the trip, they undergo smoltification—essentially, salmon puberty—transforming into adolescents ready for salt, colors changing from river-gravel-camo to mirrors of the open sea. Then, each fish at a different time will hear the call of its natal stream. It will turn and arc through the endless blue to find the river where it entered the ocean. Fighting the unrelenting current, the salmon follow the scent of their birth streams home to spawn and then die. In death, they give life, feeding critters and bugs and fertilizing the waters that made them.

All five main species of Pacific salmon are found in Alaska, one of the world’s last salmon strongholds. My cousins had gone there to fish for cohos, but we were too early for silvers. We had our hearts set on Chinook—king salmon—the largest and most elusive.

Without a guide, following advice from locals at bait shops, Walmart, and the river’s edge, we failed in increasingly slapstick ways to catch a king. I caught rocks, trees, a thousand sticks, and a double serving of humble pie. One night, I stood in a river so thick with fish it felt like a Pearl Jam mosh pit. A lunker swam into my leg and sacked me like a quarterback in the pocket. Dad smirked and said, “There’s a reason they call it fishing, not catching.”

In seven days of dogged fishing, I hooked a single Chinook. It was in the Kasilof River. It bowed my rod and buckled my knees and fought, fiercely and invisibly, behind the curtain of milky-blue glacial melt. Before I could lay eyes on it, the line snapped. My heart ached as if I’d lost a playoff.

When I heard why kings are so hard to catch, I thought someone was pulling my leg. As they return to fresh water, salmon stop eating, which subverts the whole premise of fishing: Fool a fish into biting a hook with something resembling food. (Except bass. They’ll eat damn near anything.) I’ve been told that salmon bite out of instinct or irritation, like a dog snapping at a bee.

In the final hours before our flight home, I attacked the river with desperate hope, fishing feverishly until my family dragged me out of my waders, kicking. The only thing we pulled out of that creek was an orphaned glove and me.

A few weeks after leaving Alaska, my father was diagnosed with lung cancer. Stage IV and inoperable. He got to meet his grandson but died about two weeks shy of his first birthday. Six months later, on the Fourth of July—Dad’s birthday—we drove his boat into the Gulf and poured his ashes into the salty blue. He would never teach my son how to fish. That job was now up to me.

Born in Alabama, my son is smoltifying in Idaho, where we moved when he was ten. On the last day of summer that year, we were fly fishing on a trout stream in the Salmon River Mountains when we chanced upon spawning Chinook. Those raggedy fish had swum more than seven hundred miles—upstream, through eight dams, climbing around six thousand feet—to reach this mountain stream. I felt a lump rise in my throat.

That moment inspired a mother-son fishing journey, following the salmon from source to sea. For the past seven years we’ve snowshoed, hiked, rafted, cruised, and fished our way from the headwaters of the Salmon River in Idaho to the powerful Snake, and finally down the mighty Columbia, where we fought and landed the epic fish I had failed to catch with my father. I’m passing on his lessons. I’m also learning new things.

I’ve come to see salmon as my anadromous patron saints—the embodiment of tenacity when life feels like an upstream battle against a ceaseless current. Their life history reminds me what we owe the next generation. What of ourselves can we give to the world to ensure that our children will thrive?

My son was a boy when we started this quest. Soon, he’ll be eighteen. Next summer, our last before college, we’ll fly to Alaska to catch a king salmon.

See the other articles in our For the Love of the Game collection:

In Pursuit of the Ancient Tarpon of the Everglades, by Monte Burke

The Heart-Pounding Rapture of a Wood Duck Morning, by T. Edward Nickens

Man vs. Turkey: The Quest to Outsmart a Gobbler, by David Joy

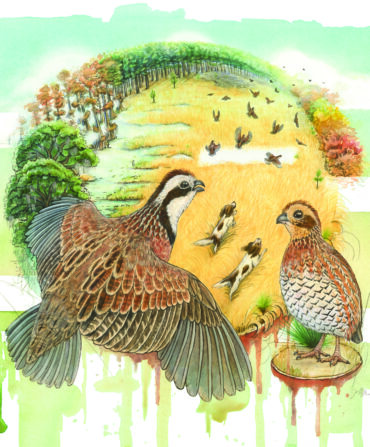

A Quail Hunter’s Ode to the South’s Signature Game Bird, by Russell Worth Parker

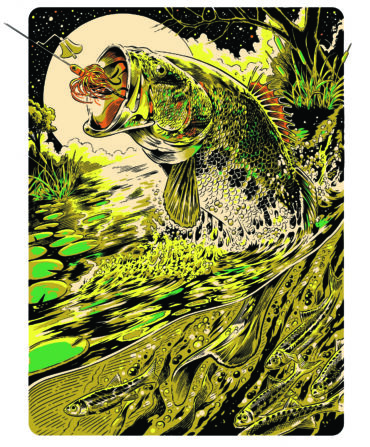

A Love Letter to Largemouth Bass, by Charles Gaines