It’s not uncommon to grow up, as I did, around black-and-white images of family members who came before. Still, as an adult, I’ve come to understand that it isn’t typical for a photograph of a dog to be the most talked-about among them.

Every time my grandfather Richard Earl told me stories about his long-gone dog, Baron, he would extend a brass-framed photo of that muscular canine. Always, I would accept it with a somber nod. Because Baron is the dog who died defending my grandfather’s life.

How this heroic dog came to be part of my family is, like most stories featuring my grandfather, one of epic proportions. It starts in a dim-lit bar, postwar Germany.

Richard Earl—a career Air Force employee—was stationed in Munich, where he’d joined a townie hunting club. It was in that smoky men’s lounge that he first heard talk of ghost dogs the color of quicksilver, large animals with floppy ears that made them endearing. Tales of their prowess intrigued him so much that when he was reassigned to the American South, he decided to look into taking one of those mysterious animals with him.

Weimaraners, that’s what the Germans were calling them.

Europe was still charred from World War II, and even the friendliest locals were tight-lipped about the dogs he sought. But Richard Earl—a handsome man with slicked-back hair and pewter eyes—was gifted with languages and people. In his club, there were a few members who’d stay late after meetings, smoking and drinking too much. My grandfather made sure he was one of them. In early morning hours, he secured intel about an elderly Polish couple who were rearing Weimaraners for sale.

His friends advised against traveling close to the Russian border. But Richard Earl had seen warfare up close. He had served in the South Pacific, and he was not easily intimidated. When he finally made it to the reputed breeders’ house in Poland, he found a darkened, ramshackle hut right out of a Brothers Grimm fairy tale.

After the couple showed my grandfather around their farm, they invited him to share a meal. Before they sat down to eat, his hostess became distraught, feeling around the top of her head, searching for a pair of eyeglasses that had gone missing. She called to one of her dogs and instructed it to search a field, where she thought the glasses might have fallen during morning chores.

The field was vast. Richard Earl was dubious. How could a dog possibly find her glasses? But ten minutes later the dog appeared, jaws tenderly gripping a pair of metal-framed spectacles. And that was that. My grandfather had no idea how he was going to secure passage for an animal on his upcoming transatlantic voyage. But, between bites of steaming cabbage, he declared that, no matter the cost, he would travel with one of those magnificent creatures.

The young dog he procured was the same height as my then-four-year-old father. My grandfather named him Baron, thought to derive from the Latin baro, meaning warrior. For Richard Earl, product of a hardworking blue-collar family, Baron was a metallic badge of honor. Because, like him, Baron had come from humble origins. Yet this dog was a prodigal son, of a lineage that had clearly risen above all expectation. They shared a certain hardscrabble nobility, this Earl and his Baron.

Returning from his service abroad with Baron in tow, my grandfather experienced the pride of an explorer who’d discovered an exotic species. Weimaraners were not recognized by the American Kennel Club as a breed until 1943. And it wasn’t until 1952, the year Richard Earl brought Baron to his new home in Florida, that the first Weimaraners were officially recorded in the United Kingdom. That year, as they so often had before, my grandparents packed everything they owned into steamer trunks. Once stateside, they rented a trailer for Baron’s crate. But when my grandfather heard Baron whimpering, he couldn’t stand to leave him alone. So, much to my grandmother’s chagrin, Baron rode shotgun.

My grandparents’ Florida was a land that had not been dredged and developed. Orange groves and swamps pocked nearly every neighborhood. They were assigned a white cottage with blue shutters and an ocean-view porch. In that house, their daily lives became softer, more comfortable. Nearby, a seldom-traveled road twisted through otherwise inaccessible swamplands, and Richard Earl loved exploring it with Baron. During their walks, Baron transformed from a foreign souvenir into a beloved hunting partner.

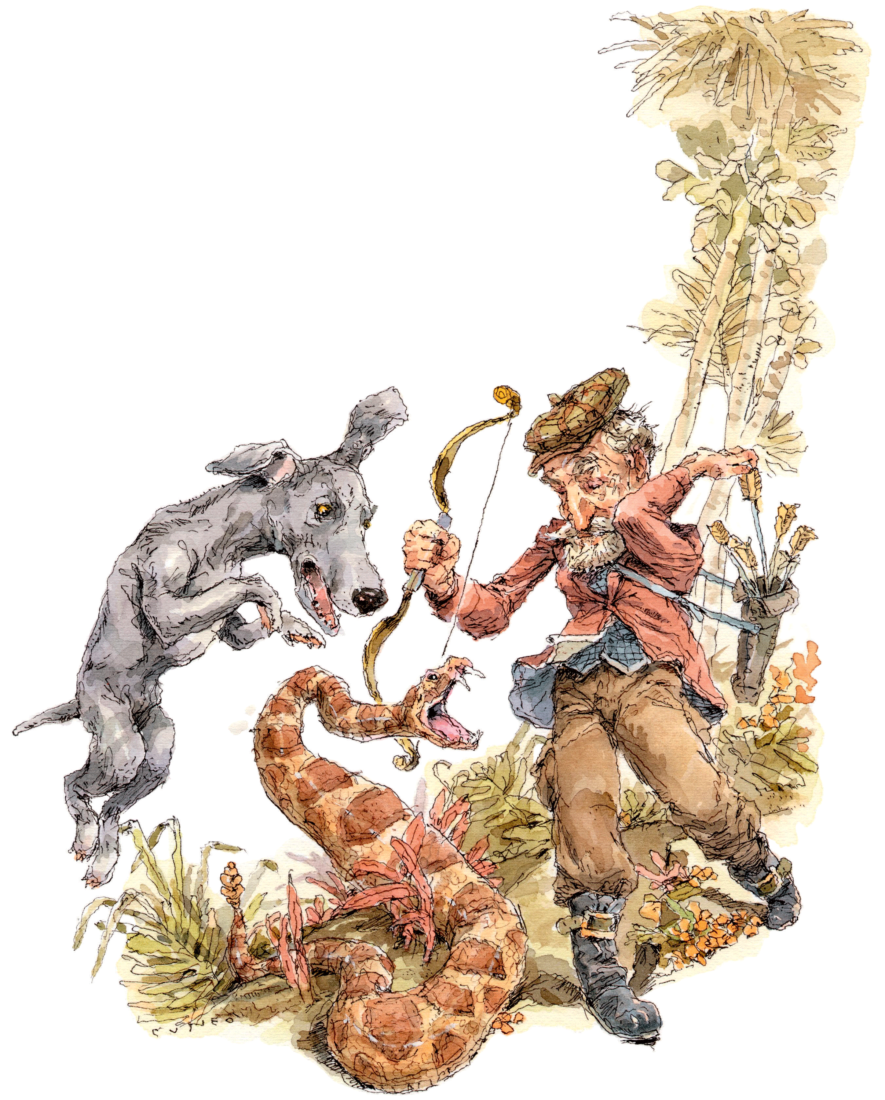

Richard Earl almost always carried a bow with him back in those days. Occasionally, as he and Baron strolled, he would shoot at rabbits to secure dinner, a throwback to his Depression-era childhood. But most often, the walks through the swamp were uneventful. Contemplative. A chance to hone his senses. There were sandpipers, storks, and ducks. There were also rattlesnakes. Richard Earl could usually spot them from a distance. But not always.

One day, he came upon a rattler as thick as a man’s arm. It was five feet long and half hidden in a patch of grass. My grandfather nearly stepped on the snake before he heard the husk of its tail rattling. It was only when he was too close to turn back that he saw the creature’s flicking tongue and raised head.

Placing an arrow onto a bow isn’t like cocking a gun. It takes the transfer of a shaft from a quiver, a careful nocking. It takes distance for fletching to catch the air needed to soar. The process requires time and space. And, standing in that swampland, those were two things my grandfather did not have.

He groped at his quiver as the serpent flew to strike him.

Richard Earl’s fingers were not fast enough. But his dog was. Baron lunged in front of my grandfather, his face soon hidden in foliage. During the scuffle, Richard Earl finally managed to fit an arrow against his bowstring.

He reared. Exhaled. Shot.

With limited visibility, through bamboo-tough grasses, he pinned that rattlesnake to dirt like a butterfly in a collector’s case. But not before the rattler had bitten Baron, pushing its fangs into the soft flesh of the dog’s nose. Already, his body was swelling from venom.

Baron had delivered my grandfather from what could have been a writhing, dark sort of death. And the knowledge that my grandfather could not—no matter how he tried—save his comrade brought a crushing sort of pain that was, for him, too familiar.

It was hot the day Baron was killed. Suffocatingly humid. Sitting there, with Baron’s head in his lap, my grandfather recognized that it would be hours before a car came down the swamp-lined road. They were a long way from the South Pacific, thousands of miles from the Russian border. But Richard Earl was still a soldier. And Baron was a warrior, wounded in the field. So my grandfather did the only thing he could. He lifted Baron into his arms and carried that savior home.

My grandfather never spoke about the pains of war, the ones that gave him nightmares into old age. But when he talked about Baron, sometimes, he cried. So did I. In fading family photos, I studied Baron’s face as intently as I studied those of my deceased aunts and uncles and great-grandparents. The dog was a spirit among ancestors to be honored.

During a difficult stint in my early twenties—when I had a dead-end job, a dying relationship, and a crushing sense of loneliness—I was friends with a man whose dog seemed to have walked right out of the photo I grew up admiring. If it hadn’t been for Baron, I probably wouldn’t have been bold enough to ask if I might spend time with that Weimaraner, as I didn’t have a dog of my own at the time.

I was living in coastal North Carolina. There were no orange groves, but when my friend was at work, I’d take his dog for long walks on hard-packed beach sand that gave me space to think and, ultimately, helped me chart a better life path. That dog was, in his own right, a gentle giant who loved to give paw-on-shoulder hugs. But, for me, his likeness to Baron was an additional salve, a reminder that grace often arrives unexpectedly—and, not uncommonly, in the form of a dog.

More than half a century has passed since Baron died. Richard Earl is, himself, now nine years gone of natural causes. But he willed to me that framed photo of Baron, and my eight-year-old son has started asking about it. Whenever he does, I let him add his fingerprints to tarnished brass, and I share the family story that might help him understand, at an early age, that humans are never alone in shaping history.