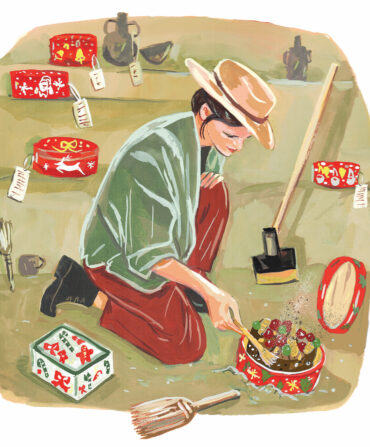

Coulter Fussell never knows what she will find donated on the doorstep of her studio in Water Valley, Mississippi. A dowager’s mink, a cheating husband’s neckties, a rotting piece of Astroturf—anything could be in those Hefty bags. “Once I got a beaver’s tail,” she says. The weirder the scraps, the better. Her friends and neighbors know Fussell will use it all, crafting quilts from the refuse, occasionally wielding a power tool alongside a needle.

“I know it looks like an episode of Hoarders in here,” she says. But every county dump should be so artfully inspired in its recycling. For most of its history, the quilt, regarded as more craft than art, has celebrated symmetry in recurring, kaleidoscopic patterns of gingham and calico. Fussell has instead brought punk-rock swagger to this corner of artisanal Americana. She works exclusively with donated tools and materials, taking a painterly, collage-like, found-art approach to the medium, which often ends up looking like a Southern Gothic iteration of abstract expressionism. Some of these quilts can swaddle you; a few might poke your eye out.

Fussell is about as far from the stereotypically gossipy, giggly quilting bee as you can get—she’s a no-bull sass-meister who speaks her mind. “I heard someone use the phrase ‘humble quilt,’” she says. “What on earth is humble about a quilt? It’s an intimate thing with thousands of pieces that touches your body. I have a maximalist sensibility. I like them bright, loud, and big. Go big or go home!”

In 2020, Fussell had her first solo museum exhibition at the Halsey Institute of Contemporary Art in Charleston, South Carolina. Curator Katie McCampbell Hirsch recalls it vividly. “Coulter declared: ‘I’m an artist. I make quilts.’ I heard that not as someone who didn’t want to be called a quilt maker, but someone who wanted to ensure that her medium was given the same weight and consideration as Art with a capital A.”

Tastemakers endorse the designation. The 2016 Atlanta Biennial included Fussell and her work, and three years later she won a United States Artist Fellowship, which came with an unrestricted $50,000 award. In what is now a famous anecdote among Mississippi bohemians, she was working as a server at Saint Leo in Oxford—waitressing at local spots such as Ajax Diner was her on-and-off “day job” for twenty years—when she got the news. “I have to go back inside,” she told the caller. “I’ve got a full section.” She finished her shift but nowadays has more time for sewing.

The artist grew up in an atmosphere of creative ferment and cultural preservation in Columbus, Georgia. Her father, Fred, is a folklorist and worked as a curator at the Columbus Museum, and her mother, Cathy, is a nationally recognized traditional quilter.

“I idolized the artists around me,” Fussell says, name-checking family friends Benny Andrews and Eddie Owens Martin (who called himself St. EOM, of Pasaquan), as well as Alma Thomas, whose work filled the Columbus Museum. She earned a BFA from Ole Miss in 2000 and began painting, but then switched to textiles in 2014. “I learned a lot from my mother by osmosis,” she says, “but I was also determined to do my own thing.”

“Coulter approaches her work as a trained painter,” Cathy Fussell observes, “and her themes are personal and feminist. My work is almost always celebratory of the landscape, of literature, of color and form. But sometimes each of us crosses over. We occasionally ask each other for advice.” And they have been known to echo each other. Mother makes “map quilts” with meticulously appliquéd rivers. Daughter has been working on what she calls “river raft quilts,” which showcase items needed for a Huck Finn–style journey: planks, fish wells for storing fresh catch, stars to guide you, inflated sheets for flotation. “Rivers,” Coulter says, “have always figured big as themes in our work.”

Like all things Southern, Coulter Fussell’s quilts tell a story. “I can do with textiles things I couldn’t do with paint,” she explains. “Part of the beauty of the process is that donated fabric may be torn or sun bleached. One T-shirt had Willie Nelson’s autograph on it. So most of the work is already ‘done’ in that sense. It’s been lived in, loved on, cast off; it has a history you can see and feel. There will never be a lack of old textiles, so I will never run out of material.”