His name was Zephyr back then. He was about a year old and close to seventy pounds, with a brown, black, and brindle coat that told the story of a wild and varied genetic background (most likely the offspring of at least one Australian shepherd). The woman at the foster home said he came from a shelter in Missouri after living on the street. He was a tender loving fool, and my two kids and I were smitten immediately. We went home to await the judgment of the foster group.

It had been many years since I’d had a dog in my house. I’d done the math a hundred different ways, but as a touring musician, I couldn’t quite get to a solution that didn’t rely on the kindness of friends and the expenses of kennels. But as I remember a writer once quipping, there was a hole in my life the size and shape of a “medium-sized brown dog,” and in the end I decided to fall back on an old tactic of mine in these kinds of situations: Just do the thing and figure out the particulars later.

After a week of consideration that felt much longer, we got the green light. My kids and I went to pick up the beautiful mutt on the way out of town to visit Grandma. On the drive, I told them I didn’t think Zephyr was the right name. He was starting a brand-new life, after all. I grew up a Minnesota Twins fan in the eighties and nineties. I’ll spare you the back-and-forth, but we ended up naming him Hrbek, after the gregarious first baseman Kent Hrbek, my favorite player on those classic teams. Shortly after we arrived at Grandma’s, Hrbek found the cleanest corner of carpet in the entire house and promptly defiled it. Welcome back to dog ownership, I thought.

Back at our home in South Minneapolis, Hrbek/Zephyr became fully Hrbek, and as luck would have it, I had the good fortune to meet Bob St. Pierre, the cohost of a local outdoors radio show. I did not grow up hunting, but I did grow up in the outdoors, fishing and camping with my family, and I loved listening to the hosts extol the wonders of chasing pheasant and walleye, of gravel roads and early mornings. One morning my band’s name, Trampled by Turtles, came up on the air. Flattered, I reached out just to say thanks, beginning a conversation that brought Bob and his cohost, Billy Hildebrand, to one of our concerts. As we hung out backstage, Bob asked me if I would be interested in going on a pheasant hunt with him, and after I’d completed my hunter safety course in various backstage rooms around the country, we went on that hunt. I felt intimidated, excited, and dumb, but also welcomed and, in the end, amazed. A new world opened to me. But it was missing something, namely a bird dog.

My partner, her daughter, and their dog eventually moved in with my kids and me. It is a loving home, if not a spacious one. With bird hunting beginning to occupy more space in my mind and house alike, I again faced a math problem I couldn’t solve: I wanted a bird dog, but there was simply no room for a third pup. Then one Saturday morning I was listening to Billy and Bob on the radio while they were chatting with a well-known hunting dog trainer, Tom Dokken. I don’t know if my particular situation had anything to do with it, but Billy posed the question of whether it would be possible to train a mixed-breed dog to hunt. Tom demurred a little, landing on what I heard as “maybe.” He also said he didn’t want everyone who owned a mutt to start calling him about it.

I immediately picked up the phone and called him about it. I got the kennel’s head trainer, Mike Wieben, who gave about the same answer: “Maybe?” We decided to give it a shot.

Almost as soon as Hrbek began his bird and gun training, getting him used to the sounds and smells of the hunt, I got a call from an apprehensive Mike. “Since you left, Hrbek has lost all interest in retrieving anything,” he said. “I can’t get him to focus, and I’m sorry to say I don’t think it’s meant to be.” I was disappointed, but I didn’t hold it against either man or beast. Hrbek would continue to be a great friend, and someday I would get a “proper” bird dog. As I was walking to my truck to pick him up early the next morning, Mike called again. “I don’t know what happened,” he began. “This morning Hrbek started retrieving like a dog possessed. Let’s give him some more time and see if it sticks.” I was overjoyed, and so proud.

Hrbek’s two weeks of training over, I headed down to pick him up. When I got there, Mike asked me to hide behind a spruce tree on a hillside so I could get a view of the Hrbek show without distracting the pupil. I watched him execute a pretty decent retrieve, dropping a training pigeon at Mike’s feet, and I almost cried. I don’t think any of us really thought it would happen. For a pound puppy with no kennel lineage, retrieving a bird seemed like a huge accomplishment. I felt like he was doing it for me.

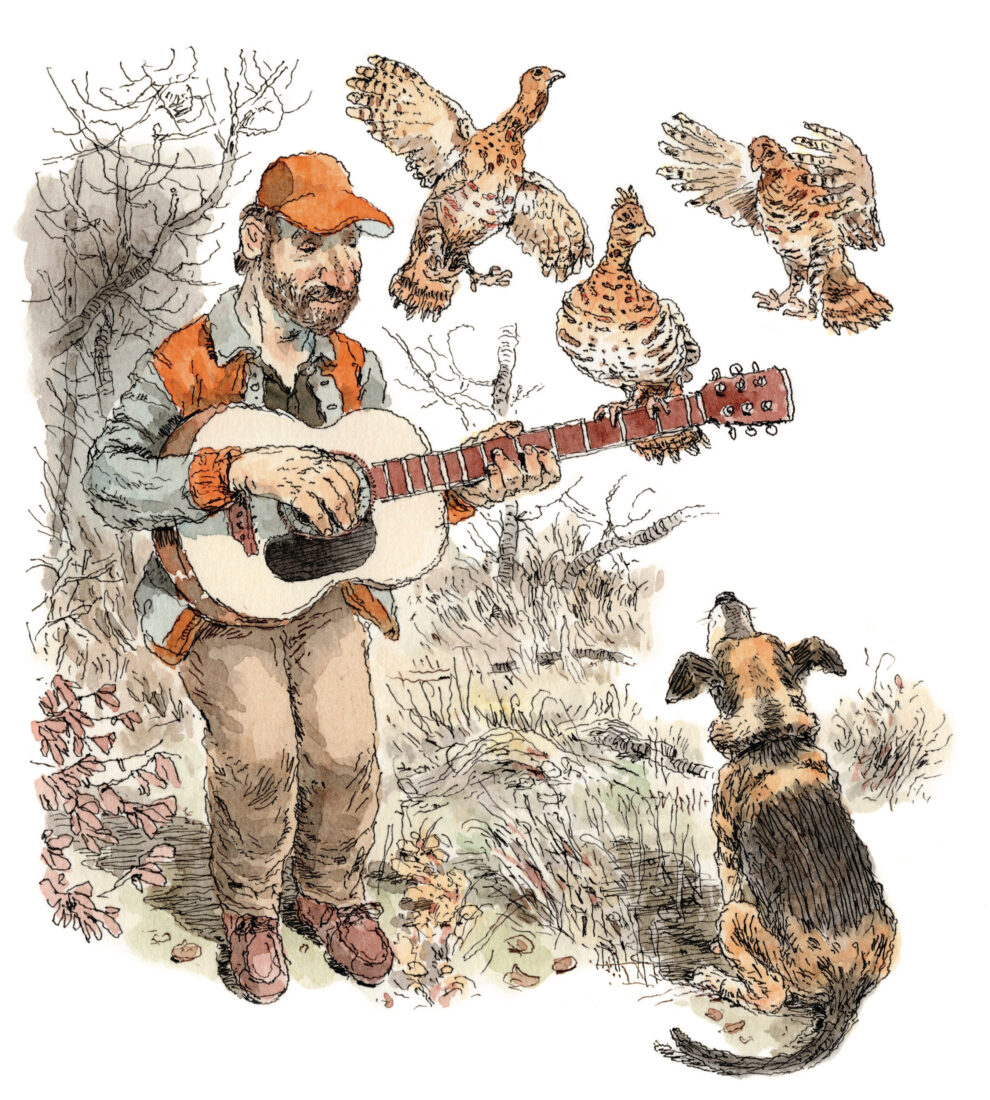

That October, Bob invited me and Hrbek to a bird hunting camp in northern Wisconsin. We were after grouse and woodcock in an impressive expanse of young poplar and birch forest. I had gotten home from tour late the night before, drained from weeks on the road. Touring in a band is a life I love, but the long hours, crowds, noise, and substantial amounts of social interaction left me very much looking forward to a walk in the woods. When we arrived, Hrbek was visibly excited by all the people and dogs, and I was not overly confident he would be flushing or retrieving anything—a notion proved true when a woodcock flushed on its own shortly into our first walk. I shot it, and my hopeful heart sank as Hrbek simply circled around the other people and dogs in the party like, well, a shepherd. I finally coaxed him into finding a bird I had already found just so he could get some feathers in his mouth.

With the daylight waning, I decided to take Hrbek and go off on our own, heading down an old logging road. The trees looked a little older than prime grouse woods, but I was enjoying the walk on that beautiful autumn evening. Then Hrbek got birdy. It was the first time I could tell he knew for certain a bird was close by, and he soon flushed a grouse. I raised my gun late and missed an easy shot, but I could see where the grouse landed. We stalked over, slowing down as we drew near. Hrbek again went into action, his big shepherd body running an olfactory slalom course in front of me, nose to the earth, clearing leaves and brush in near ecstasy. Sure enough, a second flush. It never gets old. This time I was more prepared. I brought down the bird, and Hrbek ran to where it fell and picked it up gently. With some fervent calling on my part, he brought it over to me and somewhat reluctantly gave it up.

Coaxing aside, he had flushed and retrieved his first bird. He was now, officially, a bird dog. I flipped him over on his back and scratched his belly. The remaining daylight fading fast, we rushed back to share the news.

Hrbek and I both came to this life later than most and upon an unusual path. Neither of us are purebred hunters. But against those odds, we have become real partners in the field. Since that first foray, Hrbek has flushed and retrieved many birds, with just me and on hunts with friends. Now when he sees the shotgun and the vest go into the truck, he runs in circles and squeaks like a drunken field mouse.

He still bumps or misses a bird now and again, and I still miss my share of shots. But we have both almost gotten the hang of hunting upland birds. We often look at the map together, imagining new places and new birds. I recently met a writer in South Carolina who has invited us there to look for quail, and I can’t wait to see if we can find them as well. As with any dog in our lives, I know there will never be enough time with Hrbek, whom my daughter Lucy calls the “secret hunting dog.” Our time together will no doubt run out before either of us is ready, so I treasure every hunt with him for the unlikely and incredible event it truly is.