I am bent over the sink washing my face when a tiny siren wails from my chest. Sonder has been watching me from the bathroom doorway, and at this he throws his coonhound head back and runs baying toward the window in search of the source. Well, shit, I think, as I pause to assess my pulse. Sonder and I are still getting to know each other, learning our respective ticks and tocks, so he has no idea that the siren is coming from a small bionic box in my chest, an ICD/pacemaker implanted there to help regulate the many rhythms of my unpredictable heart.

Sixty beats and steady; “it’s not me, it’s you,” I tell the machine. By now Sonder has returned from the window. I pick up the remote device that enables me to send a transmission from the pacemaker to the doctor’s office, where the technician can determine what the implant is whining about. As the dog hovers with worried curiosity, I glance reflexively toward a small cherry box atop the dresser. The box brandishes a brass nameplate that reads Remy; inside lie the ashes of Sonder’s predecessor. In one of those great plot twists of irony that the universe doles out, Remy’s heart, like my own, was ultimately too big, and even all of the love and loyalty it held for nearly ten years couldn’t save him. But before that, he was the one who helped me mend and manage my own.

In February 2010, after months of casually perusing the Petfinder adoption site, I stopped my scrolling on a light-eyed, speckle-faced puppy called Chance. Typically drawn to the spaniels and setters of my childhood, I didn’t know what intrigued me about this little Plott hound, but I knew he was the one. The rescue group told me his mother came from a high-kill situation in Georgia, and she’d given birth to the puppies in November, just two days before my own birthday. They’d all be at an adoption event the following weekend. I drove up from Washington, D.C., where I had recently moved for a job at the National Museum of Natural History, to New Jersey to meet him. It was love at first milk-toothed bite. Rembrandt “Remy” von Chance came home with me on Valentine’s Day.

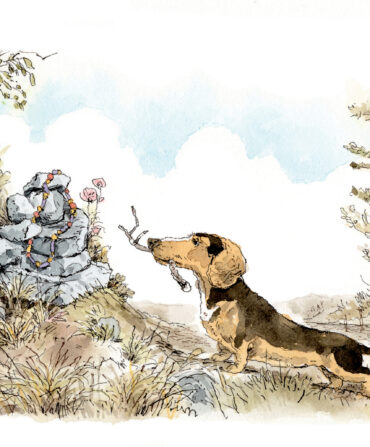

Remy grew from a floppy puppy peeing on snow mounds during a record-breaking Southern winter into a long-eared, loud-mouthed hound who barked at fish and stood on his tiptoes for ice cream. He loved the river. He loved running through the woods. He loved me. When Remy and I found each other, I was in many ways a young and stereotypically starry-eyed twentysomething trying to save the world. But in other ways, I wasn’t. I had grown up with a congenital heart disease, and my first experience in D.C. wasn’t when I moved there as an idealistic young professional, but rather at age five when I enrolled in a study of pediatric cardiomyopathy patients at the National Institutes of Health. That first winter of Remy’s puppyhood, one of the wires connecting my pacemaker to my heart broke and had to be surgically replaced—a risky procedure that involved laser cutting around the veins. Afterward, it was hard to haul around a young hound, and Remy seemed to intuit that. He made himself content to curl beside me under the covers and watch the snow.

The hound stayed by my side through heartaches of other kinds, too—loss of romantic partners, career fits and starts, familial struggles, writerly pains—as well as during life’s more beautiful moments, many of which he was responsible for. We copiloted up and down the East Coast, enrolled in therapy dog training, and eventually made visits to rehab centers, libraries, and hospitals as a team. We learned and ran the agility ring. He was as comfortable and charming visiting a Senate congressional office as he was rolling in horse manure on a Virginia farm.

The year I turned thirty, my world imploded. I’d lost faith in changemaking and quit my job at a wildlife conservation organization; my then partner ended our eight-year relationship; and I moved back in with my parents. What a millennial poster child I’d become—unemployed and licking my metaphoric wounds while scraping to pay for health insurance to cover the real ones. All I had left, I felt, were the two constants of my life: Remy, as steady as a heartbeat, and my writing.

Once again, he offered me the answer. For centuries, philosophers and scientists alike have called our species’ capacity for complex language a crucial marker of human uniqueness. I was familiar with this hypothesis and maybe even believed it. And yet, Remy spoke to me every day. His capacity for connection, for understanding, for “reading a room” (and responding to it!) was undeniable. He knew my routines and often what I would do before I did it. His communication was deliberate: When he was on alert, his tail curled into a question mark; when he wanted to divert my attention from the screen, he used his nose to unplug my computer; when he was annoyed, he looked me in the eye and barked until I changed my behavior. Remy’s uncanny cognizance prompted my desire to return to school to learn more about his mind: There was no doubt of his sentience, but what of his Umwelt—his experience of the world, so different from my own yet so obviously intertwined?

As I wrote in my doctoral program application essay later that year, “Not a day goes by that the mere fact of this other (non-human) animal’s and my cohabitation, our shared existence and our fluent communication, doesn’t fill my mind with wonder.” This still holds true, and still motivates my work each day, now as an evolutionary anthropology researcher studying canine cognition and human-animal interactions. Today I examine the underlying mechanisms of how dogs communicate, especially with humans. I study their behavior, evaluate their brain activity, and look at the ways both genetics and their environments influence the types of “people” they become. The more we understand dogs’ minds, the better companions and caretakers we can be for these animals who play such a critical role in our society.

And so, among many other gifts, Remy helped me become unlost. He gave me, a lone woman in the world with a heart condition that is oftentimes restrictive, freedom to explore spaces and places I never could have alone. He inspired a course correction, direction and purpose when my life lacked any. He was my compass. My comrade. My ever-ready study participant.

As I sat rubbing his velveteen ears one day in the spring before covid began, I noticed a distinctly familiar abnormal rhythm in Remy’s jugular pulse. When the culprit turned out to be a cardiac tumor, I was devastated. There wasn’t a specialist in the country who could help him. Losing him provoked a grief so heavy I didn’t think I’d ever be whole again—and I’m still not so sure. But even his death, I realized, eventually opened my own heart to a new kind of connection.

Everything I have learned from and because of Remy I have a chance to give back. I can use it to build something with a second abandoned being, thrown on the side of a dirt road in Kentucky. I can use it to try to understand the inner workings of the dog mind, and his heart.

I turn back from Remy’s ashes to Sonder’s inquisitive copper face.

Sonder |sahn-der| n. 1. the realization that each random passerby is living a life as vivid and complex as your own. 2. a dog; your dog; half mountain cur, half Treeing Walker coonhound, small for his breed.

This slight, reserved hound differs in so many ways from his predecessor. But his eyes, rimmed with heavy gothic liner, await my next move. As the siren in my chest sings again, this time there is no baying. Instead, he holds his gaze and tilts his head—a canine sign of processing. He’s learning. I hit “send” on the transmission device.