“They’ll be here in four minutes. We must leave now.” That was my dad talking on Labor Day evening in 1980. Summer lingered in the North Carolina air. We lived on a four-acre farm in Davie County, and my parents had company coming for supper and to watch a college football game.

By then, the countdown was familiar to me. My dad and I were going streaking over the entire property, and the trick was to get back to the house without getting caught. It was 7:26. Guests were set to arrive at 7:30 sharp.

We launched from the front door—my then-forty-three-year-old father and me, in what to Dad was like one of Junior Johnson’s moonshine runs, the revenuers closing fast behind us. Dad’s grandfather had been a moonshiner, so it was in his blood. We dashed around a cement-block barn, careened through an equipment building, darted back across the lawn under a weeping willow, and made one final lap around the house, all buck naked. As we zigzagged the final 150 yards, headlights appeared in the driveway. We could see the finish line—through the sunroom, then safe into the house—and made it at the last second. Home free.

Moments later, Dad appeared fully dressed. Mom was putting the final touches on the rib roast. Our guests arrived blissfully unaware of the mad scramble that had just unfolded.

I shared this story at my father’s memorial service last November. “Dad, we never got caught,” I said. “Until today.” Some relatives would have preferred I talk about what church John S. Meroney attended and his Bible study group or his career as a stockbroker. But in my mind, Dad will always be the greatest sprinter of all time. The man who went from naked to dinner-party attire in sixty seconds. My first hero.

Jimmy Stewart once said that the wonderful thing about the movies is that they give us little, tiny pieces of time that we’ll never forget. Dad gave me a thousand of those in real life.

The first time I heard his voice, he was cheering in the reception area of the maternity ward of Wesley Long Hospital in Greensboro the night I was born. He was so excited that the nurses had to shut down the party. I don’t remember it, of course, but on every birthday, starting when I was about six, he would tell me the story. I’m going to miss hearing that this year.

My dad liked to quote the father of American psychology, William James, who is often credited with saying that human beings can alter their lives by altering their attitudes. Dad said he owed what he called his “winning attitude” to his mother. “She was the kind of person who always looked on the bright side.” He instilled that philosophy in me and said I could accomplish anything I wanted if I had the right attitude about it, and I took that to heart early.

I loved The Andy Griffith Show from when I first saw it in reruns as a boy. By the time I was thirteen, I so idolized the show (which had been out of production for sixteen years) that I wanted to go all the way to Hollywood to interview the cast and writers. Did my father look at me like I was nuts? Nope. He flew with me and videotaped all the interviews. It was the kind of enthusiasm and unwavering support of my crazy ideas—which also included starting a campaign to find a town in North Carolina that would rename itself Mayberry—that Dad showed me all my life. He ended every phone conversation with “I love you, and I’m proud of you.”

But talking about his own challenges didn’t come easy for him. I was eighteen before I learned he had married someone before my mother. I’d flunked a class, and Dad wanted to illustrate a point. “The marriage was brief, and I made a mistake,” he said. “You can bounce back.” I was too stunned to ask any questions, and he never spoke of the marriage again.

He did often like to recount his athletic career—going back to his junior high days when, as he said, “I fell in love with this thing called football.” Many people told him he was too small, but a coach at what was then Washington-Lee High School in Arlington, Virginia, encouraged him to try out for the team. When the final cut came, Dad was seventh string, left halfback. “Johnny the Seventh,” they called him.

So, my father learned to tackle and carry the ball. Last fall, as I looked through his papers, I found clippings from the Washington, D.C., newspapers. He transformed himself into the top scorer on the team, which also included Warren Beatty. Dad was “the hard-running halfback” who “heads for the wide-open spaces.” “There goes Meroney,” read the caption of a 1954 photo of him breaking away from a tackler.

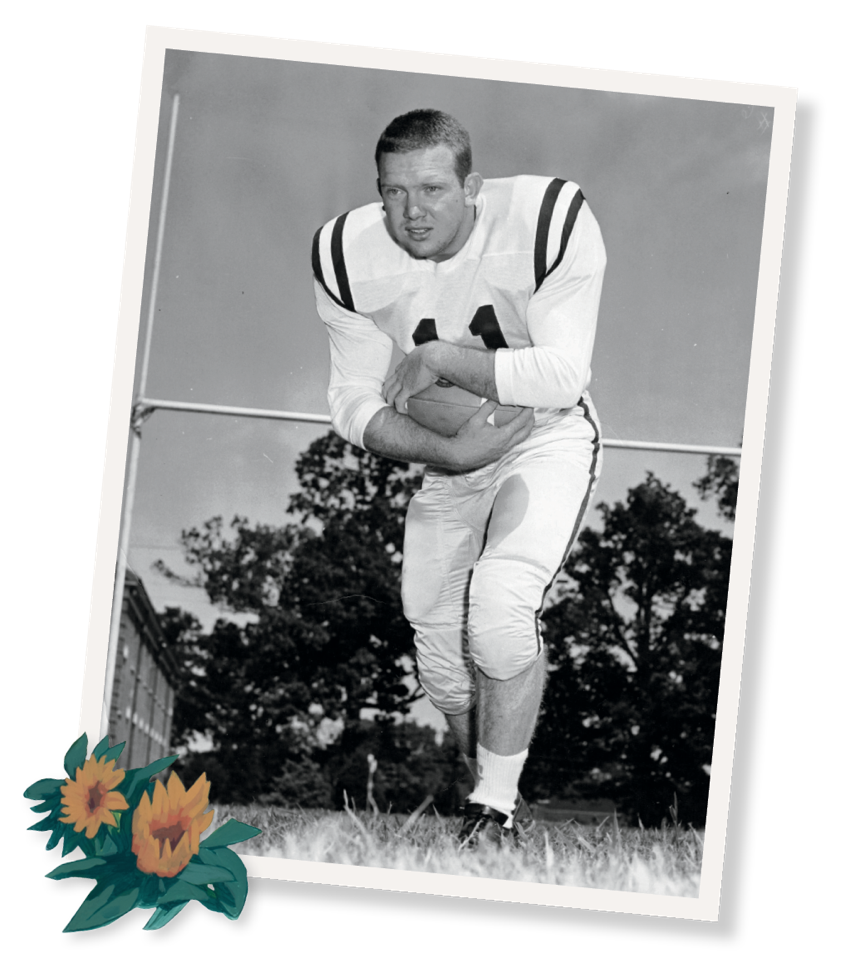

After high school, Dad was recruited to play at “the South’s Only Quaker College,” Guilford College in Greensboro. One reason he accepted was because at a small school, freshmen could play varsity, and he said he had one primary goal: to become Guilford’s first all-American.

On his first play, as a halfback against Elon, Dad ran ninety-six yards for a touchdown. His second play, he ran ninety-eight yards and scored again. Then he scored a third time on another long run. He set multiple school records and was also the team’s best tackler for four seasons. Still, Guilford struggled against tough teams. Dad said he sometimes felt like giving up. But one afternoon following the 1959 season, Guilford’s athletic director, coach Herb Appenzeller, called him into his office. “I want to congratulate you,” Appenzeller said, shaking his hand. “You’re the first athlete of any kind in the history of Guilford College to be named all-American.”

Dad graduated with honors in 1961, Guilford retired his jersey (number 11), and in 1974 he was inducted into the school’s Athletics Hall of Fame. “There was a chance of failing,” he liked to say. “I took a chance, and man, thank the Lord for the opportunities we have of failing because without them there’s no chance for succeeding.”

He was determined to excel at everything, which is what made his announcement in 2010 so shocking: After forty-four years of marriage, he was divorcing my mom. Even though I was an adult, it still hurt to see my family breaking up. I was embarrassed. I told him I didn’t respect his decision and pleaded with him not to go through with it. When he called a couple of months later and said that he was getting married again (he had proposed while watching the Super Bowl), I lashed out and reminded him he didn’t have a good track record in the marriage department. It was a short call.

I was living in California by then, and our talks would resume, but things had grown frosty. I just couldn’t reconcile the happy family I’d grown up in and Dad’s plan. A few weeks before he remarried, he wrote me, “I love you just as much now as when you were born. However, our current relationship pains me greatly. I want to resolve the conflict and move on.” I didn’t attend his wedding.

It would be almost nine years before I saw my father again. In that time, I fell in love with my now wife, Meredith. As I contemplated marriage, I gained a clearer understanding of the intimate connection between husband and wife. How different it is from parent and child. And I came to realize that the dissolution of Dad’s marriage to Mom should not be the dissolution of his life with me. Despite his flaws as a husband, he’d been successful as a father.

Before I proposed in 2017, I called Meredith’s dad to get his blessing. I also called my father with the news. I said I was nervous, and he cheered me on, and thankfully, Meredith said yes.

Dad and my stepmother, Marsha, traveled to Palm Springs for our wedding the next year. At a dinner hosted by my future father-in-law, Dad told stories about me as a child, and I got him talking about football. But it was evident he had lost a step. Before the ceremony, he was standing near my mother, dreading having to climb a hill to get to the chuppah. Dad motioned toward a young guest with a flowy dress and said to my mom, “Let’s get one of those powerhouses to walk us up there.” Mom told him that I would be escorting her to her seat, thank you very much. I’m not sure how Dad got up the hill, but he was right there in front when I said, “I do.” At the reception, I heard a song by the Drifters playing and spotted him dancing the Carolina shag with the mother of one of my wife’s friends.

Dad and Marsha had a mountain cabin in Boone, and he would often call me from there. If I didn’t answer, he’d leave a voice mail: “I’m standing up on this mountain watching the sunset, thinking about you out there in California.”

In 2019, as Dad was turning eighty-two, I felt I needed to see him, so Meredith and I traveled to North Carolina. I was still nervous around him at first, but one day we drove up to Boone, and he showed me the view westward. Several times during the trip, he encouraged us to move back home. I told him that was the dream. When it came time to say goodbye, we gathered in the kitchen, and I broke down in tears. “I’ll take care of him,” Marsha said. Soon after we returned to L.A., a package arrived in the mail. It was a book of North Carolina real estate listings, from Dad.

On my birthday in 2021, he called to wish me well and, of course, retold the story of my birth. I thanked him and said, “Meredith is looking forward to celebrating with me, but she can’t drink any champagne.” “Oh?” he replied. I let him wonder about that for a few seconds. “She’s pregnant,” I said. He shouted so loud I could hear his smile. Meredith gave birth to our first child, Blair, that December. I stepped out of the hospital room and called Dad to tell him how beautiful she was. Then I added, “I want to be the kind of dad you were to me.”

We were at home last summer when Marsha called. “Your dad’s had a stroke,” she said. As Meredith and I packed our burgeoning family (including our dog, Winston) to go see him, I wondered if we were also packing for a funeral. Marsha said Dad was bedridden. He’d been listless for days. When we arrived, I introduced him to Blair. Holding her close to him, I kissed Dad on the forehead and said, “Meet your granddaughter.” His blue eyes locked in on her. He seemed to be wondering if she was real.

For the next few weeks, we would sit by his bedside while Marsha looked after him. We took Blair for her first taste of North Carolina barbecue, and when I told Dad, he whooped. One brilliant Saturday afternoon, Meredith and I brought Blair to the football field at Guilford. We let her crawl across the goal line, the same one Dad crossed so many times. We even watched Monday Night Football together. Standing next to him one afternoon, I asked what he thought of his only grandchild. “Fabulous,” he whispered. It was the last word I ever heard my father speak.

On the evening of November 25, 2022, Meredith, Blair, and I were at my aunt’s house nearby, visiting with my mom, when Marsha texted: “You need to come home.” Dad died at around 10:00 p.m.

Since then, I look at his many trophies, which we brought back to California and keep around our house. I wear his wristwatch, a gift his parents gave him when he graduated from college. I play Flatt and Scruggs’s Carnegie Hall album, one of his favorites. But the thing that keeps him closest is the legacy he left me as a father. The lessons he taught me. The vision I have of the father I want to be to my daughter.

Dad, I love you, and I’m proud of you.