Olivia Manning is sitting in her Garden District living room, drinking champagne with two of her closest friends, and looking slightly askance at a hand-painted sign on the mantel reading “Will You Be Our Queen?” The friends are there for moral support; the champagne and sign are courtesy of a delegation from the Audubon Nature Institute, which operates the New Orleans zoo. The group had come to implore Olivia to be chair of the following year’s fund-raiser, known as the Zoo-To-Do, and they’d pulled out all the stops, bringing along the Institute’s chair as well as a boom box playing the zoo’s unofficial theme song, the Meters classic “They All Ask’d for You.” By the time I turned up—after pushing past the almost constant handful of tourists who come to pose in front of the house where Peyton and Eli Manning grew up—she’d already said yes. “After all that,” she said in her soft Southern drawl, giving me about half an eye roll, “how in the world could I say no?”

Olivia Williams Manning is no stranger to being queen. She grew up in Philadelphia, Mississippi, the eldest daughter in a family that was its own brand of royalty. In 1907, her grandfather and great-uncle founded the Williams Brothers Store, a legendary (and still- thriving) institution in nearby Williamsville that was featured as early as 1939 in National Geographic, where it was cited as a source for everything from “needles to horse collars,” as well as for being the nation’s top seller of snuff. Her mother, Frances, reigned as May Queen of her junior college and became the second female pilot to be licensed in Mississippi. In Olivia’s senior year at Ole Miss, the same year she became Mrs. Archie Manning, she was elected queen of the homecoming court; her new husband was the most famous—and beloved—quarterback in the SEC.

In New Orleans, where the Mannings have lived since 1971, she is known as a champion of causes, including the Red Cross (she’s on the national board) and Longue Vue House & Gardens, as well as a gracious hostess. (Just before the Saints won the Super Bowl two and a half years ago—by prevailing against Peyton’s Indianapolis Colts—she held a black-and-gold party for legions of female friends, including Mrs. Drew Brees and Saints co-owner Rita Benson Le-Blanc.) Finally, to pro ball fans everywhere, she is nothing less than the heart and soul of a great American football dynasty—mother of no fewer than two Super Bowl MVP quarterbacks as well as an always fashionable fixture in the stands.

For all that, says Mimi Bowen, owner of the New Orleans boutique Mimi and one of the friends in Manning’s living room that day, “Olivia really doesn’t like to be the center of attention.” Which is not to say she’s ever been a wilting flower. “Oh God, no. She loves to laugh and have a good time. But she’d rather be the one who stirs the pot and then sits back to watch what happens.”

So far, there’s been plenty to watch. The Mannings met during their freshman year at Ole Miss when Olivia and some friends gave the carless Archie a ride from campus into town in her brand-new Mercury. He knew who she was, he tells me, but then so did everybody. “How could you miss her?” asks Archie’s former teammate and roommate Billy Van Devender, now a Mississippi businessman. “She was tall and beautiful and also really smart.”

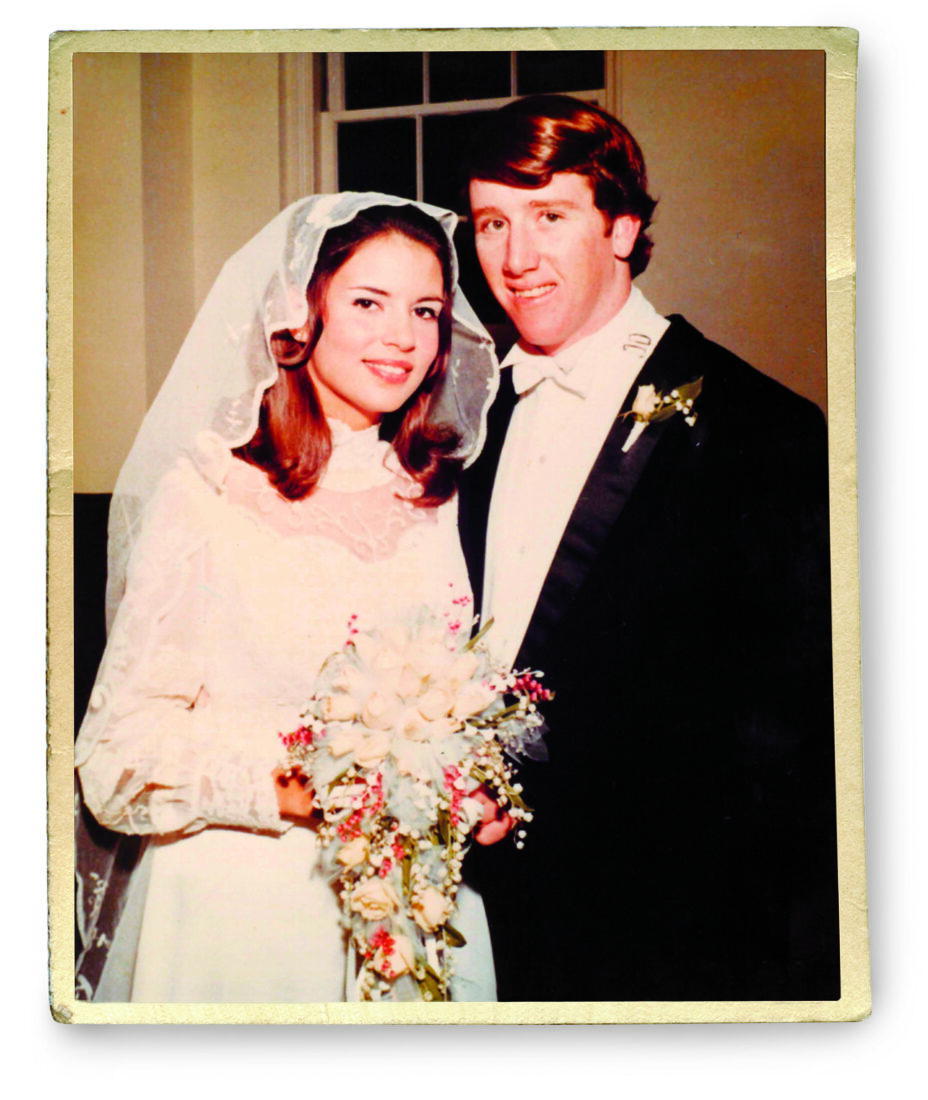

For her, it was not love at first sight—like the rest of the team, her future husband had shaved his head. “We didn’t really talk to women until we had hair,” Archie says, which meant that it wasn’t until spring, at a Sigma Nu/Delta Gamma mixer, that they finally shared a dance. When he asked her for a date, she reported the news to her father, an Ole Miss alum who’d been taking her to games since childhood. He was “real excited” about the football aspect of things, she says, but there was also the fact that “Archie was a sweet boy.”

After a summer in Fort Worth, Texas, at the John Robert Powers modeling school, she returned to Ole Miss, where Archie was the team’s starting quarterback. By senior year they’d decided to get married, but because the NFL draft in those days was so early, there would be no time in summer. Their wedding, in January, “was a zoo,” Olivia says. “In Philadelphia, you don’t send invitations locally. Friends and family are invited through the press, and the Neshoba Democrat ran my picture on a full page.” The event, which took place at the National Guard armory because the country club was too small, generated such fervor that then-Governor John Bell Williams told a session of the legislature he planned to “scalp” his invitation. He attended, but not before dispatching many dozens of highway patrolmen to keep order.

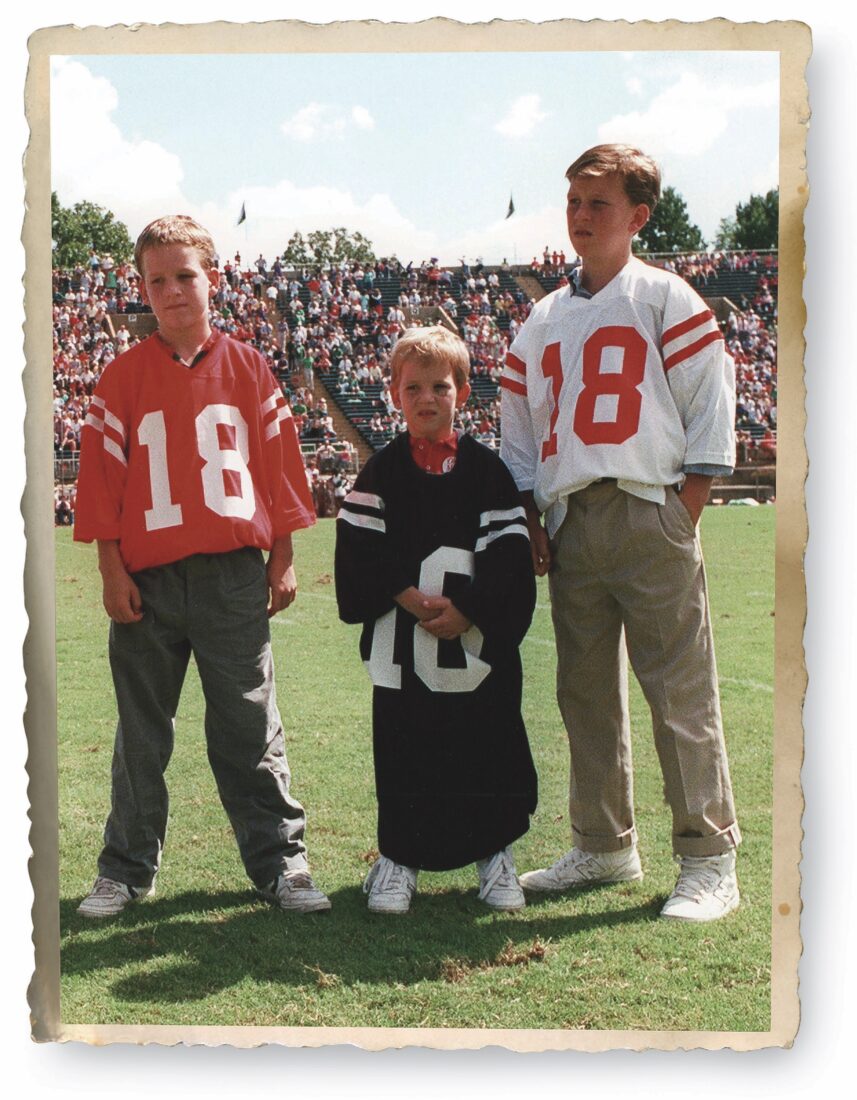

The day after they returned from an Acapulco honeymoon, Archie was chosen as the Saints’ number one pick, and New Orleans became home immediately after graduation. All three sons (Cooper, who is now thirty-eight, Peyton, thirty-six, and Eli, thirty-one) were born in the city before Archie ended his career with brief stints in Houston and Minnesota, a final step that didn’t last long. “I looked out my window one day,” Olivia says, “and I said, ‘Archie, you know those ducks or geese or whatever they were out in that little pond? Where’d they go?’ When he told me they were flying south, I said, ‘So am I.’”

Once they were home, the business of bringing up three boys continued in earnest. “We had no idea what we were doing, raising children in a place like this,” she says. “We’d both grown up in small towns where everybody knew what you were up to and told your parents the next day.” The goal, says Archie, was “well-rounded” kids. “We never had any aspirations for them to be big-time athletes.” There was no peewee football, only baseball and basketball until junior high at Isidore Newman, chosen for its rigorous academics. “If we’d wanted a football factory, we’d have chosen another school,” Olivia says, but when all three became stars anyway, she never missed a game.

Her husband calls her “the great equalizer” for her ability to “make every crisis a minor one,” but she was also the fun mom. Mardi Gras meant jambalaya and a nonstop open house. There were curfews, but all three sons agree that she was the one to get on the phone if you were in search of an extension. “She had the uncanny ability to be a mother who provided structure and discipline but who was also a running mate,” says Cooper, whose football career was cut short by a condition that narrows the spinal canal and who is now a partner in an energy investment firm. “One minute, she’d say, ‘What you did was not appropriate,’ and in the next breath it would be ‘Please put some ice in my margarita,’ but you never misinterpreted the balance.”

In summers the boys bagged groceries alongside their “Pawpaw” at Williams Brothers and moved into the family cabin during the Neshoba County Fair, still a tradition. It was important, says Olivia, that they got “Mississippi manners, that they learned to say ‘Yes, ma’am.’” The store, now run by Olivia’s brother, still sells everything from seed and saddles to clothing and hand-sliced bacon, and remains such a touchstone for Eli that he commissioned the Mississippi-born artist William Dunlap to make a painting of it.

Eli’s love of art earned him “a lot of heat” from his teammates, especially after his mother told the New York Times they’d always enjoyed “antiquing” together. “I don’t think I’d ever use that word,” he tells me now. “But since I was the youngest, a lot of the time it was just me and my mom, and I did enjoy walking around with her and seeing lots of unique things.”

Eli is her quiet son, says his mother, Peyton the most focused, like his dad, and Cooper the entertainer. When Cooper’s diagnosis required multiple surgeries, he says she “was exactly how you’d want her to be, just a great mother,” and she still watches Eli and Peyton like a hawk. “A ball could get out of my hands,” says Eli. “But if I’m not on the ground, that’s a successful play for her.” The Mannings make a point of attending the home games of each son. “It makes me feel good knowing she’s there pulling hard for me,” says Peyton, “just like when I was eight, playing baseball, and I could see her in the stands.”

Even now, she’s easy to find. Five-foot eleven and fond of animal prints, she’s such a knockout that Troy Aikman asked Peyton if she was his father’s second wife. She’s taken up bridge but hastens to add that it’s just “for fun,” and there is little chance, says Cooper, that she’ll ever be “pigeonholed into hanging out only with people her own age.” These days her youngest companions include her six grandchildren, the oldest of whom, Cooper’s three, call her Gogo.

She was thrilled when Eli went to the Giants, not least because it meant getting her hair done at Bergdorf Goodman’s John Barrett Salon and, most recently, hanging out at Saturday Night Live’s after-party when Eli was guest host. “She loves the Neshoba County Fair and sitting on our porch there drinking iced tea with some of the countriest people you can imagine,” says Cooper. “But she also wants to go to the new hip spot. It’s a great trait to have in a mother.”