The British call it Brick Lit: that genre of travel literature in which a sophisticatedly jaded man, woman, or couple falls in love with a crumbling farmhouse in some exotic, rural locale and in the comic struggle to restore said farmhouse, and via encounters with the native populace, gleans profound lessons about life, love, and local color. Peter Mayle’s A Year in Provence was the model home for Brick Lit, and that book’s success spawned a subdivision populated by writers such as Frances Mayes, Chris Stewart, and Annie Proulx. Brick Lit proved an opiate for the daydream traveler for whom being there trumps getting there—the sort of traveler longing to transplant not just himself, for a time, but rather his entire existence, possibly for good.

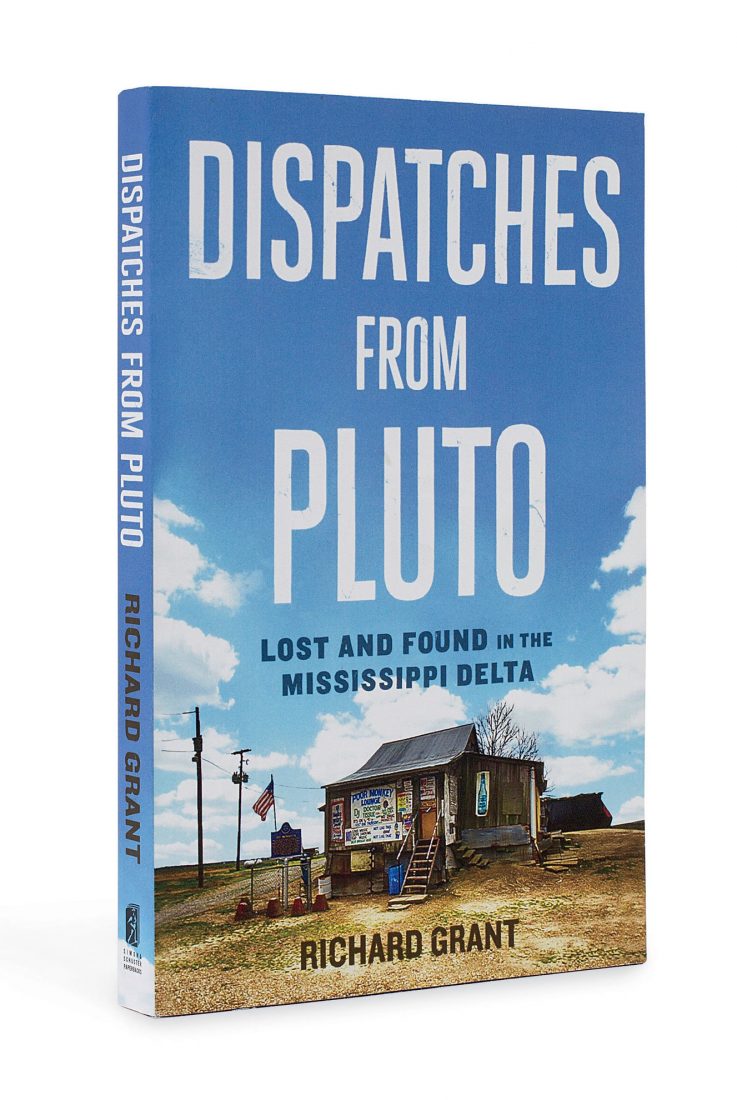

The British writer Richard Grant seems to pledge allegiance to this genre with the very first sentence of Dispatches from Pluto: Lost and Found in the Mississippi Delta: “I was living in New York City when I decided to buy an old plantation house in the Mississippi Delta.” And readers with an appetite for a deep-fried version of A Year in Provence will find much to sate them here: Grant, like Mayle, is a charmingly hapless home owner who, also like Mayle, cannot figure out how to heat his drafty house in the barely there hamlet of Pluto and so spends the winter wearing a coat indoors; he’s a wide-eyed observer of local quirks and customs; and he’s an incisive portraitist who uses piquant details to nail down his characters in much the way a lepidopterist secures butterflies with pins. He’s also very—and very dryly—funny. His and his girlfriend-turned-wife Mariah’s struggle to maintain a fresh, healthy diet in the land of fried pickles provides a steady supply of comedy, as when a cashier at a Delta Walmart examines the avocado in his basket and says, “What this is? Look like it fell out of a elephant.”

But the Mississippi Delta isn’t Provence, and Dispatches from Pluto is not, at heart, a comic account. “There’s America, there’s the South, and then there’s Mississippi,” Lyndon B. Johnson once said, and not as a compliment. The state’s Delta region, a football-shaped alluvial plain stretching from Memphis to Vicksburg, is like barrel-proof Mississippi: the highest-octane distillation of its virtues, sins, and unruly contradictions. “It was a feudal relic,” Grant writes. “It was a showcase for modern industrial agriculture. It was a foretaste of a dystopian social future, when machines free capital from the burden of labor. Sometimes it made us want to weep and scream, and return to the familiar. Sometimes we felt ruined—rurnt, as they say—for anywhere else.”

Guiding Grant’s entry into the Delta often falls to the cookbook author Martha Hall Foose, his neighbor, whose early advice for grappling with those contradictions is to “compartmentalize, compartmentalize, and then compartmentalize some more.” That means separating the good from the bad in people, especially in those whose racial or political views Grant finds repugnant or inscrutable. It means empathy, something Grant practices strenuously. He spends much of his time as a newcomer trying to comprehend the area’s haunted racial dynamic and realizing, to his dismay, that a matter so literally black and white is resistant to black-and-white answers. “It was a kaleidoscope you could keep on turning,” he writes. He gets a firmer handle on the region’s education crisis, finding gleams of hope in some progressive school initiatives in Quitman County, Mississippi. Grant is nimble on these macro issues, but it’s the individual voices and anecdotes he records that give Dispatches from Pluto its dissonant lilt and outré charm. What also buoys it is the deep affection Grant comes to feel for the Delta and its people: “My conviction,” he writes, is “that Mississippi is the best-kept secret in America.”

“Isolation, humidity, toxic chemicals” is Foose’s offhand explanation for why the Delta retains its peculiar tang. Bill Talbot, the founder of Clarksdale’s Shack Up Inn, puts it another way: “Hell, we pride ourselves on our eccentricity…You’ve got to be at least half-weird to live here, otherwise you won’t make it.” Half weird, in Talbot’s formulation, means fully in love: with a place, with a landscape, and with a culture that’s unlike anywhere else in America. Richard Grant—half weird for sure, and by Grant’s own reckoning, fully rurnt—is still living there, and one hopes that, like a deeper and way funkier version of Peter Mayle, he’ll keep chronicling it.