Long before the chef John Folse became the living godfather of Louisiana cuisine, his boyhood task was to gather kindling during St. James Parish’s hog harvest celebrations, called boucheries. In the 1950s, every neighbor pitched in, but young Johnny kept getting distracted from his designated chore. “My brothers would be hauling wood out of the swamp,” he says, “but they could always find me watching the butchers cut, watching the cooks stir, and watching the pots bubble.”

Photo: Denny Culbert

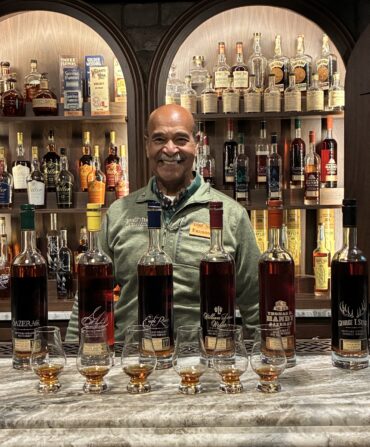

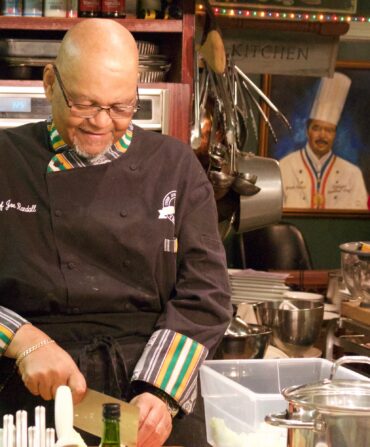

Host and teacher John Folse carves a ham.

Folse grew up to become one of the state’s foremost chefs, and in addition to running restaurants and a culinary institute and writing the definitive Encyclopedia of Cajun & Creole Cuisine, he is now a Johnny Appleseed of the Cajun boucherie. Every February, he hosts a workshop at his White Oak Plantation outside Baton Rouge to teach chefs from across the country how to slaughter a hog and cook or preserve every part of it. “This is not some big outdoor dance,” Folse says. “It’s more respectable than that—an educational seminar on how we treat an animal and prepare this food.”

The word boucherie has French origins, but for generations nearly all the people who lived along these bayous—Native Americans, Spaniards, Germans—held similar get-togethers, assembling every few weeks from October to February to slaughter hogs. Butchers divided the meat to be cured into hams and ground into sausages, while cooks prepared a communal feast.

Photo: Denny Culbert

The day dawns with the butcher’s prayer.

Over a weekend earlier this year at White Oak, two hundred of Folse’s food-world disciples congregated—along with almost a hundred ticket-holding guests—for the Fête des Bouchers (Festival of Butchers). Lee Jones, an Ohio farmer, is here to learn how to plan a similar event. Co-organizer Tank Jackson of Wadmalaw Island, South Carolina, gleans ideas for the gathering he’ll hold near Charleston this October, called Blood on the River.

Day dawns with breakfast and the Butcher’s Prayer—We thank you for the bounty of the animals. The hog who will provide this boucherie’s central lesson, Oreo, has a pedigree that stretches back to swine left on Ossabaw Island, Georgia, by sixteenth-century Spanish explorers. Oreo supped on acorns at Black Hill Ranch in Katy, Texas, where rancher Felix Florez raises heritage hogs. After the prayer, Jackson and Florez make quick work of the slaughter. An iron-blood tang is in the air, but the rich scent of frying bacon fat edges it away as Folse and his team distribute the meat to chefs at cauldron-fronted stations. Guests with cold Abitas perch among the pots, inquisitive. “Is headcheese really cheese?” No. (It’s a meat jelly made from bits of the pig’s head.)

Photo: Denny Culbert

Hog farmer Tank Jackson samples stew.

As the cooks settle in to their tasks, Folse knifes up a piece of ham and shares it with Jean-Paul Bourgeois, who grew up hunting and fishing nearby in Thibodaux and is now executive chef of New York City’s barbecue emporium Blue Smoke. “The only thing any Cajuns can agree on is first you make a roux,” Bourgeois says with a laugh as chefs begin delivering their dishes to the buffet table—backbone stew, gumbo, blood sausage, andouille, cracklings, headcheese, and boudin.

Photo: Denny Culbert

Pork sausages.

“If you taste a bit of everything, you will taste three hundred years of history,” Folse says. “But two things are more important than anything else. The need to authentically preserve this tradition. And respect. We thank the pig for the sustenance he brings us.”

CJ Lotz Diego is Garden & Gun’s senior editor. A staffer since 2013, she wrote G&G’s bestselling Bless Your Heart trivia game, edits the Due South travel section, and covers gardens, books, and art. Originally from Eureka, Missouri, she graduated from Indiana University and now lives in Charleston, South Carolina, where she tends a downtown pocket garden with her florist husband, Max.

Garden & Gun has affiliate partnerships and may receive a portion of sales when a reader clicks to buy a product. All products are independently selected by the G&G editorial team.