Out on Tangier Island, ninety miles southeast of Washington, D.C., and sixteen open-water miles from the closest mainland town, the future isn’t hard to see. It’s right there in the lapping water of Chesapeake Bay, which has submerged more than two-thirds of the island since 1850 and, gaining speed, could drown it entirely within a few decades.

At this point we’re no longer shocked by such forecasts, having absorbed louder, larger-scale predictions that, owing to sea-level rise, places such as Miami and New Orleans may one day be reefs rather than cities. Such predictions are hard to stomach and even harder to imagine. It’s likewise for Tangier’s several hundred residents, with one major exception: They don’t need to imagine it. They’re watching it happen.

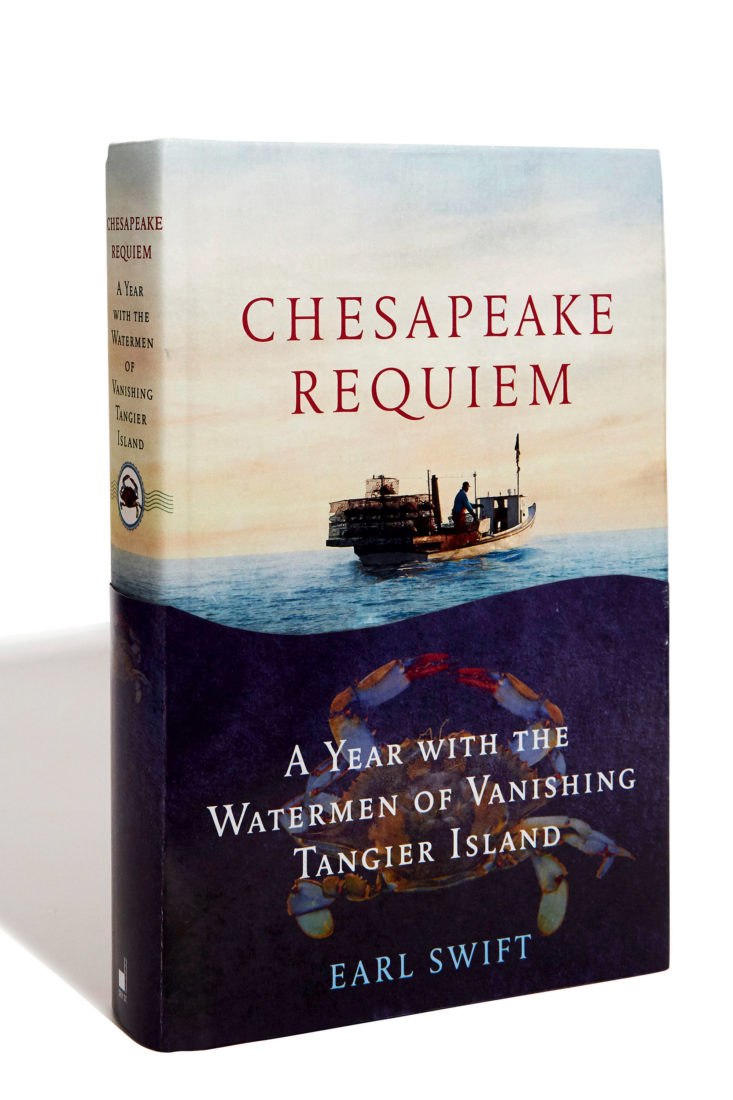

This low-lying Virginia island, roughly the size of New York’s Central Park, is likely to be America’s first climate-change casualty—“the first to go,” as Earl Swift writes in Chesapeake Requiem, a deep dive into the past, present, and narrowing future of Tangier. For Americans on the water’s edge, Tangier may be a harbinger more weighty than they realize. What happens to it—whether the government tries to save it, via seawalls or other remedies, or opts to relocate residents and surrender the island to the bay—may serve as the test run for other locales. As Swift writes, “That experience—and the uncomfortable questions it forces the country to confront—will inform what the rest of us on and near the coasts can expect in the decades to come.”

Chesapeake Requiem is not, however, a book about climate change—not directly. Many Tangier residents don’t even believe in climate change, at least so far as it’s attributable to humans. “A load of crap,” one calls it. Others merely shove the idea to the side: “I don’t care if you want to call it erosion or sea-level rise or Aunt Sadie’s butt boil,” one tells Swift. “It doesn’t matter what’s causing it.” What Chesapeake Requiem is about, instead, is Tangier itself: an isolated, idiosyncratic speck of the South reckoning with its own vanishing.

Tangier, Swift rightly claims, “is a community unlike any in America,” difficult to access since its settling in 1778. Its residents—most of whom trace their lineage to a single ancestor—have their own dialect, a “singsong brogue of old words and phrases.” Its men, “virtually amphibious,” work mostly as crabbers, or watermen, supplying many of the blue crabs on American menus. There are no alcohol sales, resident doctors, or reliable cell-phone service. “In the vast sea of styles that constitute American culture,” Swift writes, “Tangier is an island both literal and metaphorical.”

Swift’s twilit portrait of Tangier, based on a year he spent there, is immersive, sensitive, and clear-eyed. He captures the grain of the place, all its nicks and whorls, taking us into church services and to graduations and funerals and to the back room where the island’s old men pass their afternoons bantering. We spend a great deal of time on the water, most rewardingly in the company of Tangier’s mayor, Ooker Eskridge, a lifelong waterman who throws back blind crabs out of mercy (“I figure if he’s struggled this long and made it this far, I’m going to give him a break”). Swift stirs the island’s history into his pot like a bit of side meat, just enough to make it toothsome. It’s an unhurried portrait, pegged to island time.

Swift’s tone is rarely elegiac—he resists romanticizing Tangier, the way travel writers tend to do—but a mournfulness accumulates as we settle in to this beautifully peculiar pixel of America, knowing as we do that beneath those tidal rhythms ticks a very grim clock. At one point Swift boats up to Tangier’s northern tip, to root around in what’s left of the abandoned communities there, now overwashed by high tides. One of them, Queen’s Ridge, is little more than a tuft of marsh grass. “No point in searching for remnants of its past,” Swift is forced to conclude. “There’s nowhere left to look.”