One night in November, the Kernal, a.k.a. Joe Garner, was teaching his fourteen-year-old niece some basic guitar chords over FaceTime. She was a quick learner, memorizing the correct finger positions. But Garner encouraged her to run her fingers up the strings and “do something weird.” That’s where you find your uniqueness, he told her. That’s where the good stuff comes from. “It’s scary when people think you’re weird,” he tells me later over a Zoom chat from his home in Jackson, Tennessee. “But, you know, who gives a shit, right?”

Garner has been writing—and riding—his own version of weird for the past several years. Wary of being just another confessional singer-songwriter with a guitar, he established an alter ego of sorts, the Kernal, a persona he could inhabit to perform his own uncompromising version of country music. Entertainment runs in the genes: His father, Charlie, played regularly at the Grand Ole Opry as a sideman to Opry legend Del Reeves. After Charlie died suddenly, in 2008, Garner ventured into the attic at his family’s home in Pinewood, Tennessee, to look for mementos and keepsakes. He found a doozy: a red polyester suit that his dad wore at the Opry. The jacket is a bit too short in the arms, but he’s worn it as the Kernal ever since. “Stage fright really impairs the way you communicate,” he says. “I had all these great ideas, but once I got to the stage, it all went out the window. With [the Kernal], it gave me the freedom to get the most out of myself.”

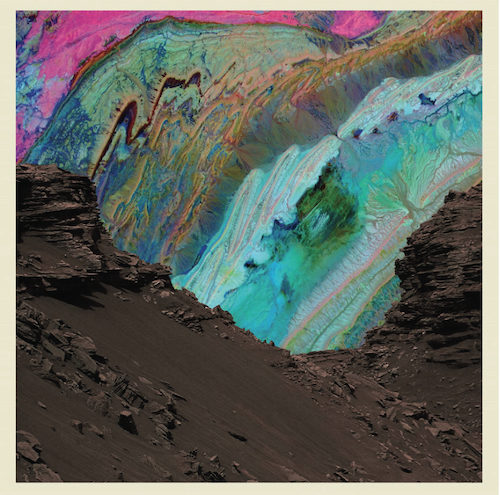

That epiphany led to a trilogy that began with 2011’s Farewellhello, followed by LIGHT COUNTRY in 2017, and now the Kernal’s new album, Listen to the Blood. The thread that connects them is Garner’s attempt to come to terms with his father’s death and the loose ends of their difficult relationship. Charlie was stern, hiding the goofy side of himself that Garner later learned he showed to his musician pals at the Opry. Nor was there much music in the household, despite his father’s coming from a family of players and singers. Their relationship remained distant, and Garner, now forty, didn’t seriously start writing songs until after his dad passed. “When you have your dad for almost thirty years of your life and you don’t feel accepted, in some ways it can be traumatizing,” he says. “It was for me.”

Along with a vintage and sometimes raucous sound, Listen to the Blood is full of vibrant characters and sly humor, in the tradition of John Prine and Tom T. Hall. While most of the songs aren’t strictly autobiographical, there are glimpses throughout of what Garner is trying to reconcile. Take the man having a midlife crisis in the swampy rock of “U Do U,” or the anxiety-laden narrator in the old-school twang of “Pistol in the Pillow” and the longing for a simpler life in the ZZ Top–esque Texas boogie of “The Limit.” And then there’s “The Fight Song,” a delicious, coy duet with pal Caitlin Rose that centers around a squabbling couple. “My wife hates that song,” Garner says, shrugging his shoulders. “It’s the only one about us.”

Ben Tanner, of Alabama Shakes, coproduced Blood at his studio in Florence, Alabama, and the songs have a dusting of that thick Muscle Shoals groove. Tanner, who also worked on LIGHT COUNTRY, says the Kernal has been one of the best-kept secrets in the Nashville scene, with Garner spending much of his time as a touring sideman for the likes of Andrew Combs and Jonny Fritz. “Joe makes challenging records, in the best possible way,” Tanner says. “His songs have a real purity to them. He’s got standards, and he’s not very interested in saying, ‘It’s good enough.’ Creatively, it’s one of the best things I’ve ever done.”

Garner says he’s going to lay his dad’s suit to rest when he starts touring again in earnest this spring. There have often been times he would imagine his dad standing in the back of the room, listening to him sing loud and strong, as his father’s family did. But he doesn’t want to confine himself to the Kernal. “I wanted to kind of put a period on the arc of this,” he says. “The red suit embodied the whole project for me. It allowed me to be someone else long enough to pull things out of myself.”