To every magazine writer, if he or she is lucky, comes one beautiful idea, both topical and evergreen, that will forever establish writer and subject, together, in the firmament of great stories. Gay Talese on DiMaggio, A. J. Liebling on Earl Long, me on worms.

It was l977, when I—who shouldn’t be the one to say so but who else remembers?—was hot. Magazines were hot, and I was freelancing for the best ones. Even my home state was hot, because Jimmy Carter, a Georgian, had just become president. And worms were hot.

Worms as in red wigglers, night crawlers, and so on. The trendiness of worms owed something to the fact that President Carter’s first cousin Hugh operated a big-time worm farm back home in Plains, Georgia. Hugh’s son, Hugh Junior, told the New York Times that his father “started out with a wooden coffin…full of gray crickets and a washtub full of worms. He probably sells 30 million worms a year now.” At that point Hugh Junior, whose master’s thesis at the University of Pennsylvania had been on the worm-raising business, was in charge of organizing the White House.

So you had that angle. But worms—which Aristotle called “the intestines of the earth”—transcended the presidency. “You would not be here and I would not be here today if it weren’t for the worms,” said an architect and worm fancier in Atlanta. “The only reason we’re alive is because of that eight inches of topsoil the worms created.” It was said that worms would eat anything even remotely organic—cardboard, baby diapers—and excrete it as 400-proof loam. It was said that the sportfishing market required some $80 million worth of worms annually, and that there was inexhaustible demand for worms as garbage disposers, as companions to large potted plants in industrial offices, and as food. The 1976 earthworm recipe contest staged by North American Bait Farms in Ontario, California, had been won by an Applesauce Surprise Cake that had edged out earthworm patties and earthworm curry. Worms were said to be 70 percent protein, high in vitamin D, and—this had the ring of truth—free of bones and gristle.

“It’s a billion-dollar-a-year business,” according to a man who claimed worms had made him a millionaire. “And probably growing faster than any other business today.” On the other hand, said a headline in the Atlanta Constitution, “Worms a Slippery Business.” The story quoted the Georgia Office of Consumer Affairs: “Questionable sellers may misrepresent potential profits, the skill and time required to care for the worms, and the commercial demand.”

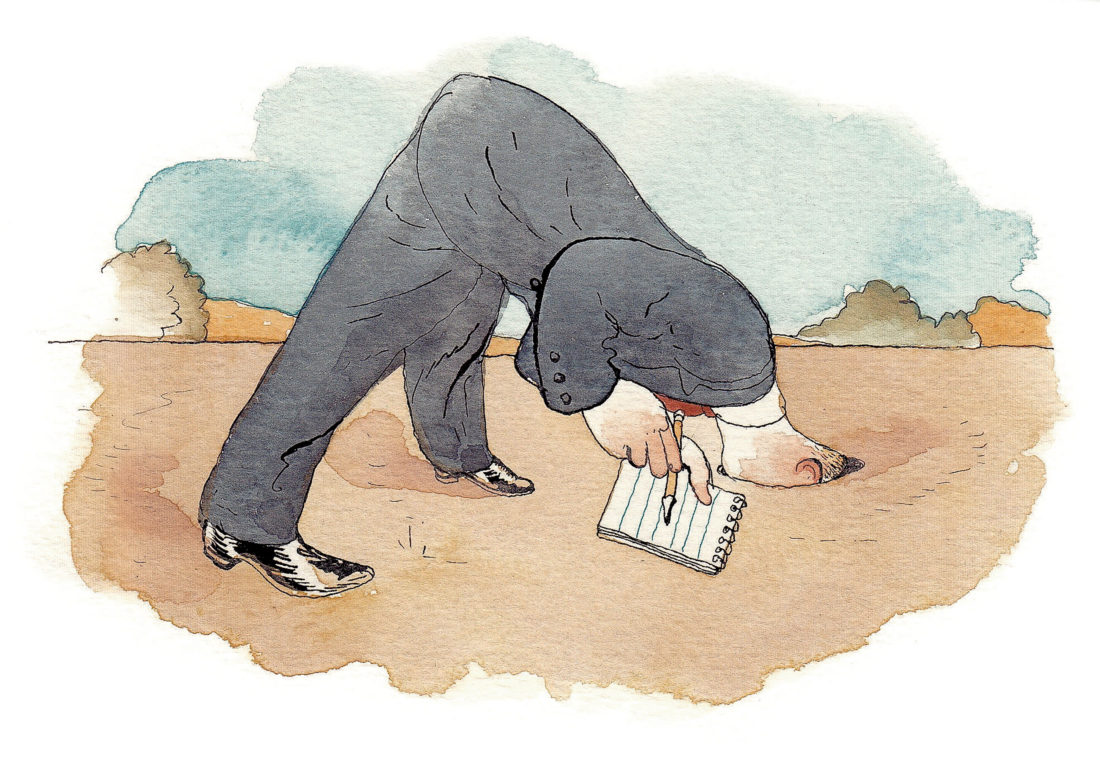

I suspected the worm boom was, in effect, a Ponzi scheme. People were selling worm-farm-starting kits on the basis that there was an ever-expanding market for worms, when the truth might just have been that there was a so-far-expanding market for worm-farm-starting kits.

One way or another, there was a lot of worm stuff going on. According to a story out of Casper, Wyoming, “A deputy investigating the theft of eleven million worms hopes a reward offered in the case won’t produce any more tips like the one suggesting he question the nearest 500-pound sparrow.”

I had already been interviewing people in bait shops. “I was using a gob of worms in my speckled perch hole, when I got a big bite, and I yanked, and nothing. Yanked again, and nothing. Yanked again, felt something, and there was an eyeball on the hook the size of your thumb. Just what it was, I do not know.”

There was a place in Albany, Georgia, whose sign read, “Wormy’s Bait and Tackle. Wormy Sez: Wiggle On In.” The best way to get the worms Wormy specialized in—sold as Louisiana Pinks—was to “grunt them up.” Drive a stake in the ground and rub it with something that caused “viber-ation,” and the worms would rise to the surface. “First time in seventeen years, I found one with two tails. Both of ’em was alive and well.”

So you had politics, economics, natural science, and Americana. I figured it for a three-parter in the New Yorker. When I sent a proposal to my editor there, Roger Angell, he liked it. He sent it on to William Shawn, the magazine’s legendary editor.

Mr. Shawn’s reaction, more or less, was “Eww.” He couldn’t stand the thought of worms.