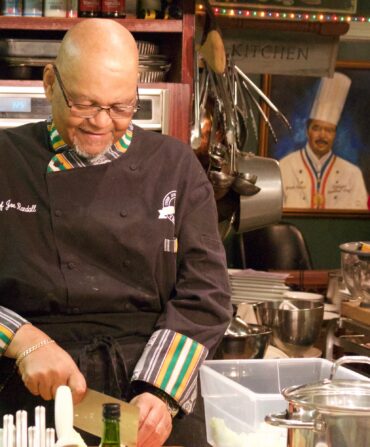

Photo: Tom Wilmes

Sampling a taste of Jefferson’s Journey.

On June 6, 2016, Jefferson’s Bourbon cofounder Trey Zoeller began a grand experiment. He and boat captain Ted Gray loaded two freshly filled barrels of bourbon onto a 23-foot Sea Pro and set off from Louisville, Kentucky, on a journey that took them down the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers to New Orleans, through the Gulf of Mexico and around Key West, and up the Atlantic coast to New York City. Two identical barrels remained in Kentucky to age under normal conditions. Would the voyage change the whiskey?

The answer would have to wait—until two weeks ago, when the first chapter in Jefferson’s Journey bourbon came full circle during a comparative tasting event held at the Frazier History Museum in Louisville. “It was a hell of a fun project,” Zoeller says, “and a testament to what people went through back then.”

Photo: Courtesy of Jefferson's Bourbon

Trey Zoeller.

Buoyed by the mature-beyond-its-years character and faint salinity of another Jefferson’s bourbon, Ocean—barrels of which are aged at sea—Zoeller sought to recreate conditions under which Kentucky whiskey historically traveled to market by flatboat, putting in just below the Falls of the Ohio and floated downriver to New Orleans and ports beyond. Zoeller’s hypothesis is that, while surrounding whiskey-producing states share a similar geology and climate to Kentucky, travel by boat is what gave bourbon made in the Bluegrass State its singular character and reputation. The effects of wind, water, temperature extremes, and time all caused the whiskey to constantly come into more contact with the charred insides of the barrels as it floated downstream.

It took Zoeller and Gray fifty-eight days to motor from Louisville to New Orleans, averaging 4.8 knots and “using just enough power to navigate the rivers and the locks,” Zoeller says. Temperatures exceeded 100 degrees for seven straight days. They landed in New Orleans in August and transferred the two barrels onto a slightly larger boat. Before they could depart, however, a tropical storm socked the coast and “rocked the hell out of our barrels,” Zoeller says. The leading edge of Hurricane Hermine caught up with them in Tampa Bay, further damaging the exposed barrels and warping and popping the barrel heads. Zoeller syphoned the bourbon into two new barrels in Key West, and high-tailed it for Ft. Lauderdale as Hurricane Matthew loomed in the distance. The category-five storm destroyed the boat they’d contracted to transport the bourbon on the final leg of its journey, so they wintered in Ft. Lauderdale and later hitched a ride the rest of the way. They landed at New York’s Chelsea Piers on June 6, exactly one year from their departure date.

Photo: Courtesy of Jefferson's Bourbon

Loading the bourbon barrels onto the flatboat.

Zoeller sampled the bourbon three times throughout the journey—in New Orleans, in Key West (“actually I tried a lot of it in Key West as I was siphoning it from one barrel to the next,” he says.), and again in New York. “In New York, I was also releasing a sixteen-year-old bourbon that had been double-barreled for five years, and the bourbon that was on the journey was every bit as dark as that sixteen-year-old bourbon in the bottle,” he says.

Both bottled at 92 proof, Jefferson’s Journey pours a sparkling amber compared to the light straw color of the Kentucky-aged control. In the sample I tasted, notes of spicy wood and wildflower honey come through in the aroma and on the palette, with a grassy undertone and slight fusel heat that’s much more pronounced in the Kentucky Aged version. Both drink like younger bourbons, but the Jefferson’s Journey version looks and tastes like it’s at least several years further along.

As with Jefferson’s Ocean, Zoeller has plans to scale up and commercialize the Jefferson’s Journey experiment. But that may come later. At the moment, he’s pleased to have completed the initial trial and to have shared the results with a roomful of friends. “We didn’t have to worry about pirates or bandits and we didn’t have to trade gold for horses to get back to Kentucky, but we still had our own difficulties,” Zoeller says. “I guarantee that the quantities of the two barrels that we aged on the journey were the most expensive bourbon ever made.”

For now, at least. At the tasting, Zoeller casually mentioned the beginnings of another wild experiment: To send whiskey samples into space.

Tom Wilmes is a journalist based in central Kentucky, specializing in bourbon and other spirits. A contributor for Garden & Gun, he has also written for Whisky Advocate, The Local Palate, Southbound, and various other publications. Follow @kentuckydrinks on Instagram.