It was the late 1950s, and I was a painfully shy and lonely teenage girl who was nearsighted and wore glasses. Not only glasses, but horror of all horrors, the ugly blue plastic kind with wings. My parents and I had just moved to a small apartment in Birmingham, Alabama’s Southside, in an area where I didn’t know a soul. That fall, I would be attending a new high school, where I would be the “new girl.” An only child, I had always longed for brothers and sisters, and all my life I had been wishing I could find a place where I belonged, where I might somehow fit in.

While waiting around for school to start, I had nothing to do. But I soon discovered, right down the street from our apartment, a charming little spot called Caldwell Park. And down at the far end stood a redbrick building known as the Town and Gown community theater. On those hot summer days, when the theater doors were left open, I could hear music and the sounds of people singing and dancing and laughing. Oh, how I wanted to get inside and see the show they were rehearsing. But I had no money for a ticket, so I had to just imagine what it would be like to see real live people singing and dancing on a stage.

Then one day something totally unexpected happened. For my fifteenth birthday, my grandmother sent me fifteen dollars in cash! I immediately knew what I wanted to do. I crossed the park to the theater, marched up to the box office, and asked the nice lady inside if fifteen dollars was enough to buy a ticket to the next show. She assured me it was. At that very moment, two men walked across the lobby. They were talking about the spotlight operator, who had apparently quit. “I don’t know what we are going to do,” one said to the other. “We open tomorrow night, and we need to find someone quick.”

To this very day, I don’t know how I got enough nerve to do it, but I walked right over to them and heard myself saying, “Excuse me, sir, I couldn’t help but overhear your conversation, and I can run a spotlight.” They looked at me with some skepticism, and I quickly added, “My father is a motion picture machine operator, and so I’m professionally trained.” Of course, it was a bald-faced lie. (Not the part about my father. But I had no idea how to run a spotlight.) The two men looked at each other for a moment, and finally one said, “Well, can you be here at four o’clock this afternoon for a technical rehearsal?”

“Yes, sir,” I said. “I’ll be here.” Then I casually walked out of the theater, trying my best to look calm and composed.

As soon as I was out of sight, I ran as fast as I could and jumped on a bus headed downtown, where my father worked at Birmingham’s Lyric movie theater. I flew upstairs to the projection booth, threw the door open, and announced to my surprised father, “Daddy, I need to learn how to work a spotlight by four o’clock this afternoon.”

The Lyric had once staged vaudeville shows, and after searching around in some dusty storage closets, he found an old spotlight and showed me the basics. I jumped on another bus and ran to our apartment in time to change clothes and make it back to the theater by four. (Full disclosure: The spotlight was not that difficult to work. All you had to do was turn it on, point it down at the stage, and know your cues. Every night I had my own private seat up in the spotlight booth.)

I later found out that one of those men in the lobby was the director of the company, a roly-poly dynamo named James Hatcher, known to everyone as just plain Hatch. And as I also found out, he was known all over Birmingham and the South as Mr. Theatre. Thankfully, Hatch took a liking to me and invited me to work on the next show, and then the next, and before I knew it, I was a regular, accepted member of the Town and Gown theater community. I went from working spotlight to taking care of props, wardrobe, curtain pulling—anything they needed, I did it. I was in heaven, and my parents were thrilled that I had finally found something I loved and a place that made me happy.

And it was a happy place. People from many walks of life made up the Town and Gown group—single career women, married couples, doctors, lawyers, teachers, and anyone who just loved to have fun and put on a show. As I was the youngest member, I was given the nickname Baby Girl, a name that has stuck with me to this day, and at my age, I like that.

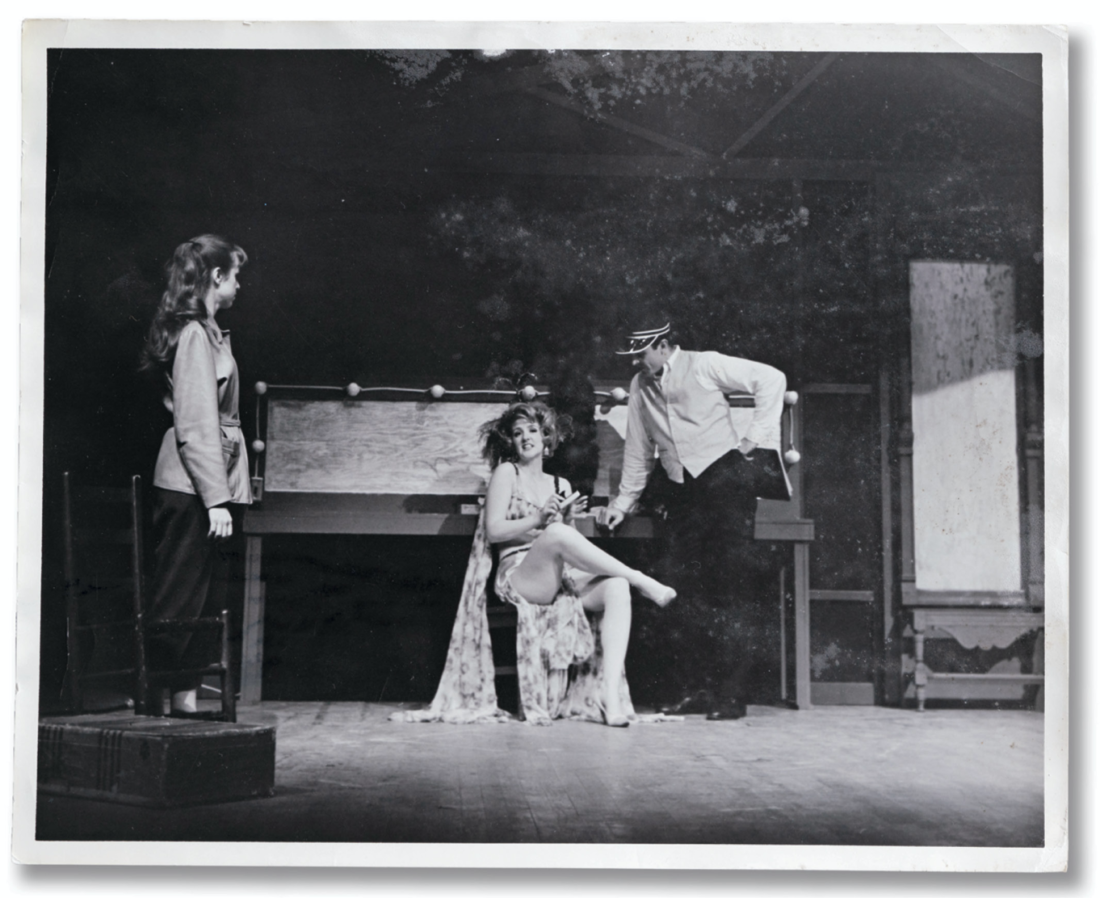

For the first year or so, all my duties were backstage, but then the theater put on the musical On the Town, and one of the characters was a nonspeaking role, simply called “Little Old Lady on Subway.” There were no real little old ladies in the theater group who were willing to stay up that late at night rehearsing, and so with granny glasses and a gray wig and a giant push from Hatch, I made my onstage debut. Soon I was playing all the old-lady parts in every play. Thus began my acting career. Later, I began writing and acting in comedy sketches for the cast parties. And thus my writing career began.

Local organizations such as the Lions Club and Rotary would hire our group to entertain at their functions. Some of us would sing and dance, and I would perform my sketches. One weekend we performed at a convention, and the owner of the local television station WBRC was in the audience. He offered me a job as cohostess on the morning show. Hatch said to take it, so I did. But I still continued to do shows at the theater at night.

A few years later, I decided to go to New York and try my luck at acting and writing in the big city. Over the years, I became a regular on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson, wrote for and acted on Candid Camera, and I also played Mona Stangley, the owner of the Chicken Ranch brothel, in the Broadway production of The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas. Thanks to the theater and live television training I had received at home, I felt prepared, but I also had a special reason for wanting to succeed. I wanted to make my parents, Hatch, and my Alabama theater friends proud of me. Years later, in 1991, at the Alabama movie premiere of the adaptation of my book Fried Green Tomatoes at the Whistle Stop Cafe, I was doubly grateful that Hatch and all my theater family were sitting right beside me, especially when I heard them say, “We are so proud of our Baby Girl.”

I am happy to report that unlike too many places of the past that no longer exist, my little Birmingham theater is still there and still going strong. It has had a couple of face-lifts over the years and now operates under a new name: the Virginia Samford Theatre. Its current president, Cathy Rye Gilmore, is a dear friend I have known since she was fifteen herself.

My beloved Hatch and so many of my theater family from back then are gone now. But even today, when I walk into the lobby, I can still see and hear them laughing and having a wonderful time. That little redbrick building was the first place I felt a real sense of community. It gave me confidence, beautiful memories, a career, and lifelong friends. I will always remember how kind they were to a shy girl who needed a place to belong.

Garden & Gun has an affiliate partnership with Bookshop.org and may receive a portion of sales when a reader clicks to buy a book. All books are independently selected by the G&G editorial team.